Oman Diary: The Sultan Qaboos - a grand mosque

Sultan Qaboos bin Said Al Said is considered a benevolent leader by most Omanis. Since 1970, when he wrested control from his father, Qaboos has transformed Oman from a third world country into a modern society. He continues to undertake social reforms and ambitious infrastructural and cultural projects. Not least among these is the Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque off Sultan Qaboos Street (his name is promiscuously attributed to Oman's finest achievements). By Malachy Browne.

(More pictures on our Facebook page here)

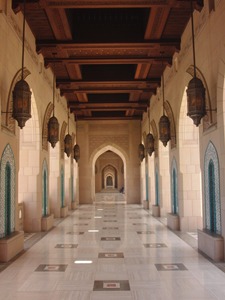

Sultan Qaboos Grand Mosque is a captivating sight. For newcomers to Oman’s capital, the mosque appears unexpectedly as one drives along Sultan Qaboos Street into the city. The principal minaret - 90m tall -gradually comes into view around a thick line of trees. Next, a gleaming 50m-high dome appears, as resplendent in the sun as it is by night (see photos). As the north-western corner comes into view, the scale of the 40,000 square-metre complex becomes apparent. Four flanking minarets (45m tall) are joined by long arcades. These 200 metre-long hallways, or riwaqs, are punctuated by open archways, pointed at the apex – a characteristic of Arabic architecture. The surrounding gardens, palm groves and outer buildings encompassing 412,000sqm. Elevated above the gardens and set against the backdrop of the rugged Al Hajar mountain range, the mosque looks fortress-like.

Externally, only a mosque’s central dome and minarets are obviously ornate - a metaphor for spiritual illumination. Atop Sultan Qaboos mosque, the central dome is embossed in gold and veiled in a concrete lattice with gold mosaics. By night it is illuminated from within, like a beacon above the subtly-lit structures.

While modesty is retained from a distance, closer inspection of the mosque reveals finer detail. Excerpts from the Qur’an are carved in calligraphy on the frieze of the inner courtyard and the upper reaches of the processional archways. Set around 10m off the ground against the backdrop of the sky, the calligraphy is meant to suggest ‘a notion of the exalted... [conveying] a higher order of knowledge’. Thuluth, the most difficult and elaborate of the six types of calligraphy, was chosen for these engravings. Thuluth is said to have ‘the capacity to be fine and delicate (raqiq), or lofty and great (jalil)’. According to one description, ‘an almost musical sensibility controls the expansion and contraction of the [Thuluth] letters, an aesthetic device carried to its highest point’.

The inner courtyard is tiled in cream marble, in keeping with the white sandstone of the Prayer Hall exterior. The mosque is constructed from 300,000 tons of sandstone imported from India and crafted in Oman. The external sandstone walls are decorated by calligraphy and stucco carvings and geometric patterns. External hallways around the buildings and courtyard are lined by open arches; bronze lanterns with stained-glass panels hang between the arches. The walls of the Ladies Prayer Hall are clad in pink sandstone, with marble inlays and floral motifs.

Although the prayer halls are named by gender, there is no strict separation of the sexes in Islam when it comes to prayer time. On one visit to the Sultan Qaboos Mosque, men and women shared the main musalla. They prayed opposite small alcoves containing a bookshelf holding verses of the Qur’an. Some worshippers touched the books as they prayed, others stood head bowed before them. Other knelt, ‘prostrating’ before the books, with hands, forehead, knees and feet touching the ground. When prayer is over, some worshippers impressively roll backward in one movement from this position, off their toes into an upright position.

Mass worship is slightly different. People stand shoulder-to-shoulder, performing the same movements in time. According to a booklet entitled ‘Women in Islam’, it is because of the synchronisation of these movements that women and men are usually separated during mass worship.

Upon its completion in 2001, Sultan Qaboos Mosque contained the world’s largest hand-woven Persian carpet (it is currently the world’s second largest carpet). Measuring 70m by 60m, it took four years to weave, weighs 21 tonnes and has 1,700 million knots.

The carpet is laid in the main musalla. An elaborately carved timber door opens to this vast room. The sight on entry is breathtaking. The patterned carpet stretches out to the furthest reaches of the room, some 70 metres away in each direction from the entrance. The central dome is magnificent, supported by four broad columns set 30 metres apart. The dome is ornately designed into stained-glass triangles. Fourty eight smaller stained glass windows encircle the base of the dome.

Hanging from the centre of the dome is a monumental crystal chandelier, gold-plated and 14m in height. Replicas of the central Swarovski chandelier hang throughout the prayer hall, illuminating the mosaic patterns around niches and stained-glass windows.

The musalla achieves its goal. The mosaics and motifs, the depth of the dome and breath of the hall, the chandelier, the niches and the vibrant colour all evoke a sense of reverence. People move slowly through the mosque; they speak in hushed tones. It is a marvellous sight, a fitting masterpiece to Oman’s finest modern structure.

More on Oman: Early morning at the fishing town of Barka