Unleashing the Dragonfly

Twenty years late and not yet complete, the International Space Station finally took shape last month, writes Leo Enright.

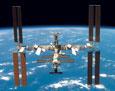

The €80bn International Space Station (ISS) finally took its intended shape last week, 20 years after designers first sketched out the “dragonfly” silhouette that was intended to symbolise a new era of human space flight and international cooperation. This picture was taken by the crew of the Space Shuttle Atlantis on 19 June as they departed the ISS at the end of a mission that included four space walks by construction-worker astronauts to attach another set of solar power panels to the station (the four panels on the right in this view), completing the distinctive “dragonfly” shape.

The station design we see today has survived the destruction of two space shuttles, the collapse of the Soviet Union, the vacillations of four US presidents and two dozen attempts in the US Congress to abandon it.

In reality, the ISS is a combination of two space stations. In 1976 the Soviet Union approved plans for a third generation of space station to replace its ageing MIR orbiting complex, while in the US Ronald Reagan announced the construction of “Space Station Freedom” during his State of the Union address in 1984. The ISS we see today is actually made up of some of the components originally designed for these two separate space stations – only its completion will have taken almost 20 years longer than either country anticipated.

Throughout the 1980s, the United States struggled to contain its programme costs, redesign followed redesign, and then came the 1986 explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger.

Little progress was made in actually building a space station, but by 1987 the overall design was settled upon, bringing Europe, Canada and Japan into a partnership with NASA to build the space station as an international undertaking.

By June of 1993 the internationalised station was again over budget and behind schedule, and the House of Representatives voted to continue the programme by a single vote (216 to 215). Three months later, the Clinton White House made a dramatic announcement – Russia would join the space station programme as a partner.

ISS construction is still far behind even the most conservative estimates that it might be completed in 2004 or 2005. This is mainly due to the halting of all NASA shuttle flights following the destruction of Space Shuttle Columbia in early 2003. During the shuttle stand-down, construction of the ISS was halted and the science conducted aboard was drastically cut due to a crew size of only two.

In recent years, modules and other structures were cancelled or replaced and the number of future shuttle flights to the ISS was sharply reduced after President Bush ordered an end to the shuttle programme by September 2010.

Even so, more than 80 per cent of the hardware intended to be part of the ISS in the late 90s is still planned to be orbited to the station by its new scheduled completion date of 2010. A crew of six is expected to be established in 2009, after almost a dozen more construction flights by the space shuttle.

The latest space shuttle mission to the ISS was a major milestone toward finally implementing Europe's much-delayed plans for human space flight aboard the station. By year's end, Europe's Columbus module may at last be attached to the station – a quarter of a century after it was first mooted.