Memories of Mick Mackey

Mackey's contribution was in refining crude bobbling and lurching into a practical skill which could be devastating when used by the right man at the right time. He was "The Laughing Cavalier", "The Playboy of Limerick" and "The Happy Warrior". And much more along those lines. Any epithet or cliche that could be used or strained to convey devil-may-care audacity, camaraderie, and abandon has been so used of Mick Mackey.

And most were accurate enough - in their time, and up to a point. Mackey did not become one of the two greatest hurlers in history by being carefree and dismissive. Skill, cunning, speed, anticipation, and sheer instinct for the game, of the Mackey order came - could come only - from the stern dedication of a rare body and mind to excellence and eminence.

Those who attribute his success to solo running are simply hopelessly adrift. Mackey was neither the most frequent nor the most successful solo runner amongst the unforgettable centre forwards. The most frequent was probably Tom Cheasty; the best was certainly Pat Delaney, who was more percipient than either in his choice of when to go, and was, like Mackey, an innovator: his knack of bouncing the sliotar from stick to sod to stick has been taken up by others, but never again performed with Delaney's eclat.

Those who attribute his success to solo running are simply hopelessly adrift. Mackey was neither the most frequent nor the most successful solo runner amongst the unforgettable centre forwards. The most frequent was probably Tom Cheasty; the best was certainly Pat Delaney, who was more percipient than either in his choice of when to go, and was, like Mackey, an innovator: his knack of bouncing the sliotar from stick to sod to stick has been taken up by others, but never again performed with Delaney's eclat.

Mackey's contribution was in refining crude bobbling and lurching into a practical skill which could be devastating when used by the right man at the right time. He was often that man. And the comparative novelty of the art, compounded with vigour, surpassing adroitness, and occasional turbulence made his solo running imperishable. But the greatest solo goal eluded him. Christy Ring scaled that summit in the All Ireland of 1946. Larry Guinan made a mighty effort to displace him in the Munster Final twenty years later. There have been other challenges, but their train grows faint on memory's screen while two great might-havebeens remain undimmed.

Starting in his own half Seamus Bannon of Tipperary cascaded through Cork's outer lines, and from thirty yards sent a rising, bending, fulminating shot past a frozen goalkeeper. And the referee disallowed it. That was 1954.

Ten years earlier, it had happened to Mackey. And it happened in the game that was his real swan-song though, he played on for two profitless years. With some fifty minutes gone Limerick were four points clear of Cork in the replay of the Munster Final. This time Mackey meant to copperfasten it. From fifty or sixty yards out, he took the high road for goal. He was fouled - twice. He kept going, and from near the 21 blasted it home. They say in Cork that the whistle went at the first foul. They swear in Limerick that the ball was nestling in the net before ever a note was heard. And Limerick missed the free! The reprieve steadied Cork, and Ring did the rest.

It was one of the very few hurling matters that Mackey was bitter about. The Limerick selectors' choice of goalkeeper for the drawn game - Cork scored six goals - was another. And the iron must have entered into many a soul besides Mackey's since those days, so grievously have Limerick been blighted by clownish refereeing and clownish goalkeeping. It is often difficult to steer a course through the storms of piffle about "dust flying in the square" "virility rites" "crashing through" and "taking him head-on" that comprise the currently popular notion of hurling in the 30's, 40's and 50's. That version would have us believe that, in his general play as well as on his solo runs, Mackey relied on a kind of unnatural strength and borderline aggression - Moss Keane with a hurley.

But before hyperbolism and sciolism there was an age of facts. Even the Cork Examiner respected them - well, its hurling reporter did.

"His spectacular runs, his dash, his cleverness in weaving his way through, and above all his wonderful stick work won the hearts of the crowd."

"Mick Mackey, once in possession, was about as easy to handle as a Shannon eel, and he once more slipped through to add a great goal."

No Moss Keane there. Rather Jack Kyle and Barry John, and every seemingly effortless master of truly arduous art.

For Mick Mackey was a total hurler, and the contrast which counterposes Mackey the claymore to Ring the rapier is as shallow as those "De mortuis . . ." affirmations of their mutual sanctity. Each possessed every skill, sleight, and ornament of the game; and if one did not quite match the other in this facet or that it means only that he was a microscopic degree short of the best. Of course, there were games and times when the methods or tactics of one or other seemed pre-eminent. The illusion usually only lasted until the next game: for neither ever stopped evolving, improving, plotting, as age, experience, and changes of position or opponent warranted.

Their respective refinements of the solo run - amounting, to others, to the revelation of new dimensions of the game - were, to them, only segments of the process of actualising the game's potential. Mackey was, indeed, strong; and perfect in judgement of when and how to use his strength. But the strongest ever? Ring thought - or sometimes purported to think - that he had met many players who were better hurlers than himself, but that he had been the strongest player ever. He was abysmally wrong on both counts - as are those who peddle the same delusions about Mackey.

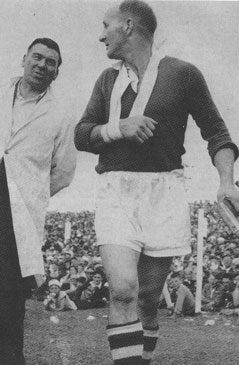

A clash in which Peter Blanchfield's collar bone was broken is often adduced as proof of Mackey's paramount strength and the glorious 'hardness' of the game in his time. Well, Michael Doyle's collar bone was broken in a fair man-to-man clash last May, and Iggy Clarke's in a slightly less fair one in 1980, and Doyle and Clarke are not weaklings. But the few who can name the breakers are not claiming that they are the strongest or 'hardest' ever. There is a place for legitimate vigour and aggression in hurling now as there was in Mackey's time, and the few decent referees we've got recognise it and honour it. Referees, as a body, were not more lucid or consistent thirty or forty years ago, even though they had a more lucid and consistent set of rules to apply.

And, then as now, legitimate vigour and legitimate aggression sometimes crossed the line into dirt. A tale is often told of Lynch switching on to Mackey one day to chastise him for an injury to a Cork player. The mission is said to have been successful. Mackey had the resentment of the strong and arrogant man - the boik - when he was thwarted; and scrupulosity was not the primary characteristic of many of his opponents. And, when Mick found maleficence proven, he believed in an eye and a tooth for an eye. So - very infrequently, be it noted - he turned foul. He was sent off twice. But in the context of fourteen years at the top those dismissals illuminate the man's essential goodwill: maleficence had to be very blatant before Mackey reacted.

He never really retired. His "greyhounds" of 1955, his umpiring antics, and his constant presence at the great occasions kept the face and the feats almost vernal. He might have been the avatar of Wordsworth's Intimations of Immortality. Haply, the bard had him, or one as great, in mind:

"What though the radiance which was once so bright

Be now forever taken from my sight,

Though nothing can bring back the hour

Of Splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower;

We will grieve not, rather find Strength in what