Trade not aid?

Previously, I have examined overseas development assistance (ODA) and the priority – or rather lack thereof – awarded to it by the wealthier nations. However, many argue that ODA is not the best way to tackle poverty and its attendant ills – the solution is increased global trading. By ensuring the inclusion of all countries, particularly poorer nations, in the worldwide trading structure and networks, poverty will be eliminated.

However, free trade has frequently been used to cloak efforts, by wealthier nations, to further strengthen their economic dominance as well as to obstruct the development efforts of poorer countries.Many economists insist the critical factor in tackling poverty is economic growth. The solution to achieving this required growth, they argue, is the increased promotion of free trade on a global basis. For these commentators, the failure to adequately integrate ‘developing’ countries into the world market is the real obstacle to the elimination of poverty.

As Mike Moore, ex-head of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and a strong free trade supporter, stated in August 2008:

“Seven years ago, we introduced at Doha what was to be a "development round". All trade rounds are. President Kennedy, who introduced the Tokyo round, famously said: 'This will lift all boats and help developing countries like Japan.' Case made, I would have thought.”

However, there are many who have questioned the link between trade liberalisation and economic growth. According to the development theorist, Richard Peet,

“...the past two decades have seen a rapid opening up to trade in developing countries… [and] trade volumes in developing countries have grown faster than the world average… this massive increase in exports has not added significantly to developing countries’ income.”

Moreover, the contemporary free trade model has been widely criticised as preventing ‘developing’ countries from introducing economic reforms suitable to their own growth and poverty-reduction needs. By imposing a ‘one size fits all’ approach, states in the global South have seen their range of development policy measures seriously curtailed.

Whereas nations such as Britain and the US utilised tariffs and other economic policies to nurture industrialisation, these options have been greatly reduced. The Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang claims that powerful states, despite having employed interventionist economic policies to facilitate their own growth, now prevent ‘developing’ states from adopting similar measures.

It is in this respect that the World Trade Organization (WTO), the foremost international trading body, has been widely criticised.

The WTO was established with the principal objective of liberalising and promoting free trade to foster global economic growth and development. However, its real contribution to increased trade is questionable. As the American economist, Andrew Rose, a free-trade advocate notes:

“Membership in the GATT/WTO is not associated with enhanced trade, once standard factors have been taken into account. To be more precise, countries acceding or belonging to the GATT/WTO do not have significantly different trade patterns than non-members.”

Moreover, many in the South accuse the WTO of double standards. Rather than being a neutral forum, they believe the WTO acts as a lever for the North to increase its economic influence. Although states in the North constantly demand market liberalisation they are often slow to do this themselves. A particular flashpoint in this respect is the North’s protection of its agricultural sector. The Trade-Related Aspect of Intellectual Property Agreement (TRIPS) has also proved highly controversial. It established a global twenty year protection period with monopoly trading rights for patent holders, which appears to fly in the face of the WTO’s free trade ethos.

Perhaps most damning of all is the fact that the majority of trade agreements, both inside and outside the WTO, have relatively little to do with the promotion of free trade. These agreements tend to be predominantly concerned with the imposition of rules, including conditions on how services can be delivered or the appropriate manner to regulate foreign investors. They appear more concerned with creating a homogenous global marketplace, where the South is at a disadvantage.

At the same time, little attention is paid to levelling the international trading playing-field and ensuring the South a greater share in our global wealth. Indeed, there is a widespread and growing conviction in the South that the North is using the concept of free trade both as a means to prise open their domestic markets while ensuring their global economic hegemony remains unthreatened. The real problem would appear to be not the South’s lack of integration into the world market but rather the terms under which it has been integrated.

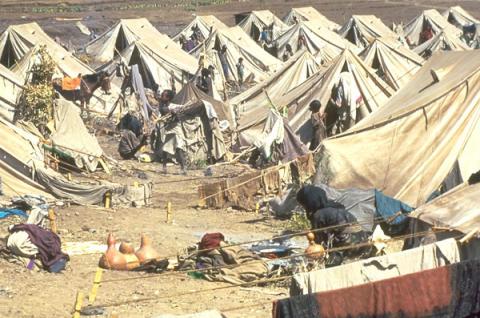

Rather than helping the South reduce the evil of poverty, the current international free trade structure is actually aggravating it. Assailed by the evils of poverty, hunger and inequality, the South, already in a relatively weakened position, is now also deprived of many of the economic policies it needs to tackle them.

Although, free trade supporters contend that the opening up of global trade has paved the way for dynamic economic growth that has, in turn, led to a reduction in global poverty levels, this decline in poverty has been predominantly in just two countries, China and India. The reality has been quite different in the majority of other countries in the South. Furthermore, research has shown that in fact economic growth in a country such as India has not appreciated significantly subsequent to its adoption of a liberalised trading system.

Indeed, the only real ‘progression’ would appear to have been the escalating growth in inequality between the winners and the losers in the global marketplace. This inequality has socially devastating consequences with increased levels of violence, higher rates of social exclusion and marginalisation, and reduced life expectancy. It would therefore appear unwise to place our hope in the ability of our current free trade system, through some sleight of its ‘invisible hand’, to alleviate the evils of poverty, hunger and inequality.

In the upcoming penultimate piece of this mini-series, I will examine the impact international debt obligations have had on developing countries. In the final piece, I will look at what obligation we have – if any –to assist states in the South in their efforts to alleviate the evils of poverty, hunger and inequality, as well as providing suggestions as to how they might optimally be tackled.