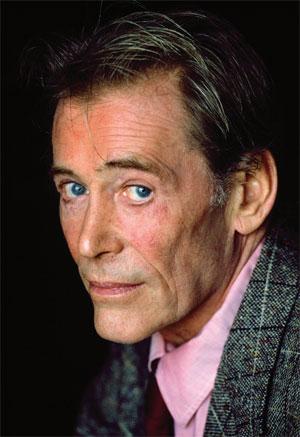

Peter O'Toole: The perfect gent

Kate O'Toole writes about her father, Oscar nominee Peter O'Toole

My earliest memories are from when I met him, almost for the first time, in Spain at the age of two. He was working in Seville, having spent the previous two years in various Middle-Eastern countries working for Sam Spiegel and David Lean on Lawrence of Arabia. The film was winding down and he had time to spend with me as my second birthday was celebrated. I was taken to a bullfight.

My chief recollection is of bossing him around and him being happy to see me push the boundaries.

Before the release of Lawrence unleashed global recognition on him, he had made a big impact on the British stage during a now legendary season in Stratford at the Royal Shakespeare Company where he played a mesmeric Shylock in The Merchant of Venice and a cracking Petruchio opposite Dame Peggy Ashcroft in The Taming of the Shrew.

It was during the latter production that I was born.

When performed in full, as it was, the Shrew is a play within a play, opening with a rag-tag assemblage of strolling players who have been travelling the country looking for a place to set up their tent. It was decided that among this troupe, there should be a newborn babe in arms. Dame Peggy carried me onto the stage and thus I made my theatrical debut (the first and last time I received an engagement due to parental influence). I am told I held my head up with a certain stage presence and fixed the audience with a steady, interested gaze. Peter said later there was “a definite whiff of actress” about me.

Life in the O'Toole household was intensely glamorous during the 1960s, but as a child I had no appreciation of that. We lived in a very imposing Georgian townhouse in Hampstead village. There were rivers of staff dancing attendance on us: nannies, au pairs, secretaries, gardeners, cleaners, seamstresses. There was a liveried chauffeur manning a fleet of cars: a Daimler, a Rolls Royce, an imported American Chevrolet, a racing Mini Cooper and a “runaround” for the nanny.

Life in the O'Toole household was intensely glamorous during the 1960s, but as a child I had no appreciation of that. We lived in a very imposing Georgian townhouse in Hampstead village. There were rivers of staff dancing attendance on us: nannies, au pairs, secretaries, gardeners, cleaners, seamstresses. There was a liveried chauffeur manning a fleet of cars: a Daimler, a Rolls Royce, an imported American Chevrolet, a racing Mini Cooper and a “runaround” for the nanny.

Since the days of Keats and Shelley, Hampstead has been a magnet for bohemian types. Authors and painters lived all over the village and we had many neighbours who might best be described as “interesting”. Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor (known to my father as “Gladys”) had a couple of houses round the corner. Peter Cook lived across the road. Spike Milligan was nearby, as was John Hurt. The poet Adrian Mitchell was down the road. Michael Foot was in the area. Peter Sellers often came to stay. The stellar parties were never ending.

The local pub would deliver crates and crates of booze down to our cellar at the start of every week. By the end of the week, those crates would be empty. A frequent houseguest during that decade was a very dear and close friend of the family, the actress Marie Kean, who liked to say that these were “The days of wine and roses. But mostly wine”. Peter's film work was constant and the Oscar nominations flowed.

Happy to have children, but not so happy to have them under his feet at all time, my father decreed that we were to be neither seen nor heard unless specifically invited into the presence. I lived with my sister and a nanny on the fifth-floor nursery, a self-contained flat with a little balcony affording charming views of the London skyline when it was still dominated by St Paul's Cathedral. After being fed, bathed and put to bed by the nanny, I would sometimes slip downstairs to peek at the action in the grand hallway if my parents were going out to a smart dinner or a film premiere that evening.

My mother, Sian [Phillips], would be dripping in Dior couture, effortlessly elegant as always, while Peter would look impossibly handsome in his achingly well-cut Saville Row finery. Thinking they were alone, they would hold hands and kiss fondly before venturing forth into the night.

There was an impressive art collection in that hallway which my father had assembled over the years: several choice Yeats paintings, a Picasso, an Epstein sculpture (known to me as the “Welsh lady called Molière”) a few Etruscan ornaments, a large and extravagantly bejewelled Persian chest and various other curios brought back from trips abroad.

There was quite a lot of jet-setting in those years. If O'Toole snr was busy filming and couldn't get home for Christmas, the family would be sent for and off we'd go to take up residence at the Crillon in Paris, the Danielli in Venice, to explore the jungle in Mexico, to travel up the Orinoco in Venezuela, to live just like Eloise at the Plaza in New York, to play poker in Sophia Loren's villa in Italy.

As an antidote to the glamour, however, there was always the bolt-hole in Connemara, where my paternal grandfather was from. He'd had family land there and my father had added to it. In schizophrenic contrast to the high life, we lived without central heating in a tiny, basic, traditional stone cottage until a bigger house was built nearby to accommodate us all.

Until that was completed, for many years my mother, father, sister and grandparents would cram into the three-roomed cottage while the entourage (nanny, chauffeur, tutor and minder) were installed in the best hotel in the town five miles away. They had swimming pools and tennis courts, we had brown water from the well and warm milk from the cow. We loved it.

My father studied books on wind geometry and planted trees accordingly, in his pyjamas. My mother dropped the Dior and grew vegetables. I helped to stack turf and make hay. We all relished and valued our time there more than anything else in the world. It's the one place that has always been a constant backdrop to my life. Despite the rootless existence that is an actor's lot, I've always called it home and choose to live there now, in the same area, where my spare time is spent wielding my grandmother's pickaxe and making a garden out of untamed coastal wilderness.

The fun came to an unpleasant end in the 1970s when, I suppose, we all had to grow up in one way or another. I started proper school and was penned in by exams and timetables. My father developed acute pancreatitis and had to have the offending organ removed, which very nearly killed him. There weren't many parties after that. The marriage deteriorated. My mother left and married a younger, healthier, prettier man. Peter's parents both died. Many of his more robust contemporaries passed way too. His manager ripped him off, badly. The mood sank and his poor health meant the job offers dwindled. It was the worst of times. But they passed.

The real meat-and-drink in my dad's life has always been his work, first and foremost. Whatever else is going on, as long as there's a good part on the table, I know he'll be alright. When his canny eye first landed on the script for Venus, he knew that the role of Maurice, the ageing actor, was one of the best he'd come across in many years. His recent Oscar nomination appeared to validate that opinion. Delightfully, it also proves he was right when he instinctively balked at the Lifetime Achievement Oscar given to him four years ago.

The real meat-and-drink in my dad's life has always been his work, first and foremost. Whatever else is going on, as long as there's a good part on the table, I know he'll be alright. When his canny eye first landed on the script for Venus, he knew that the role of Maurice, the ageing actor, was one of the best he'd come across in many years. His recent Oscar nomination appeared to validate that opinion. Delightfully, it also proves he was right when he instinctively balked at the Lifetime Achievement Oscar given to him four years ago.

After seven Academy Award nominations, that particular Oscar came far too late – and also way too early. As he said at the time, “I'm still in the game and might yet even win one of the lovely buggers.” Not that he feels he needs to – with eight nominations, he now stands as the most nominated actor in the history of Hollywood. He knows real triumphs aren't measured by ornaments, no matter how prestigious, and so he remained neither expectant nor anxious about the outcome at the Kodak Theatre on 25 February. He's too old and too talented to get sucked into all that madness. I, on the other hand, was a complete mess, demented with suspense on his behalf.

Kate O'Toole will be seen as Sister Una in the film 32A by Janey Pictures in Spring 2007