At the kingdom's edge: Exploring Thailand's forgotten conflict

Driving to Pattani from Hat Yai is much like any other journey in the south of Thailand; an ocean view lined with palm trees, rubber plantations, small towns lined with yellow flags, and large portraits of the King placed outside of municipal buildings. Yet what makes the districts of Thepha and Nong Chik different from other coastal districts in Thailand are the military roadblocks that are encountered along the route and the large numbers of military and paramilitary personnel that can be seen along the roadside as one approaches Pattani town. The idyllic coastal landscape, the small crowds gathered outside of tea-shops in the early mornings, the chaotic driving of local motorcyclists and the wandering goats are a temporary distraction from the fact that this peripheral region has been the stage for a brutal cycle of violence between state (and state-sponsored) forces and a mysterious insurgent movement since 2004. The movement’s aims, structure and membership are cloaked in secrecy. Barely any statements have been made to the press and any such statements by supposed representatives of the movement are treated as dubious by both authorities and analysts alike. {jathumbnailoff}

A member of 44 Ranger Battalion mans a remote checkpoint near the Malaysian border, in the southern province of Yala. The Rangers are a government trained and armed unit made up entirely of volunteers. They have in the past been accused of massive human rights violations in the Deep South. There are currently more than 65,000 members of the Thai security forces stationed in the three southernmost provinces of Pattani, Narathiwat, and Yala

A member of 44 Ranger Battalion mans a remote checkpoint near the Malaysian border, in the southern province of Yala. The Rangers are a government trained and armed unit made up entirely of volunteers. They have in the past been accused of massive human rights violations in the Deep South. There are currently more than 65,000 members of the Thai security forces stationed in the three southernmost provinces of Pattani, Narathiwat, and Yala

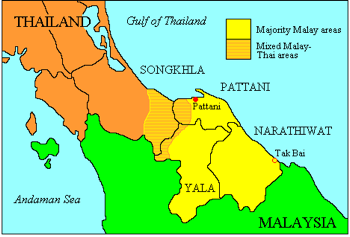

The three most southeastern provinces of Thailand: Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat (commonly referred to as the ‘Deep South’) and parts of neighbouring Songkhla are mainly inhabited by Malay-speaking Muslims, with Thai-Buddhists and Chinese-Thais forming a small but economically powerful minority. The language spoken by Malay-Muslims in the ‘Deep South’ (a dialect of Malay, referred to as Jawi by locals), the religion practiced, and the shared history of the local people, are all similar to Malays living across the border in Kelantan province, Malaysia.

Since January 2004, at least 10% of the Thai-Buddhist population has fled the ‘Deep South’, as have an unknown number of Malay-Muslims. Nearly 5,000 people have been killed and over 8,000 injured in this most recent conflict in the region. The murder of unarmed Buddhist monks and school teachers by insurgents, the deaths of over seventy men at Tak Bai (Narathiwat) whilst in military custody (November, 2004) and the destruction of the Krue Ze Mosque (a 300 year old Mosque in Pattani) during a siege by the military (April, 2004) led to much criticism of Thai security forces and the Thai state, especially the government of former prime minister, Thaksin Shinawatra (1999 – 2006).

The violence has also provoked much speculation by both the media and academics as to who the militants are and what they are trying to achieve. A whole range of arguments have been put forward and many dubious and at times ambitious claims have been made by both Thai and foreign analysts. Since 2008, there has been a sharp decline in the number of attacks in the ‘Deep South’; since then, the international media has tended to ignore the conflict as very little substantial information is available and much uncertainty surrounds most of the attacks. Events in Bangkok have also overshadowed events in the ‘Deep South’.

A heavily armed Huey helicopter gunship conducts an aerial patrol over the southern Thai town of Narathiwat. There are currently more that 65,000 members of the Thai security forces stationed in the three southernmost provinces of Pattani, Narathiwat, and Yala

A heavily armed Huey helicopter gunship conducts an aerial patrol over the southern Thai town of Narathiwat. There are currently more that 65,000 members of the Thai security forces stationed in the three southernmost provinces of Pattani, Narathiwat, and Yala

Much analysis of the conflict tends to be simplistic in outlook (bad state vs. persecuted minority) and certain claims have been grossly exaggerated - e.g. the insurgency is part of some regional ‘Jihad’. When consulting Thai-Buddhists from outside of the ‘Deep South’, Malay-Muslim activists in Pattani, or Malaysians living on the other side of the border, the inhabitants of the ‘Deep South’ are usually presented as a homogenous, uniform community of devout believers and passionate ‘Patani’ nationalists. Yet, over the nine months that I spent living in Pattani town, I found that the conflict in the ‘Deep South’, its causes, and the society that has been affected by it are much more complex than usually presented by regional experts. If anything, I discovered a place where maintaining a dual-identity is more common than fitting oneself into a simple black and white category, and a place where different influences and elements of different traditions have been absorbed in a unique and colorful way. Yet I also discovered an incredibly violent borderland, full of mistrust, silence and intrigue, where Thai-Buddhists are uncertain about their future and where Malay-Muslims try to pragmatically deal with pressures from both the Thai state and a mysterious insurgent movement who target those whom they consider ‘collaborators’; i.e. those who work for the Thai state.

[i]

[i]

The range of influences that has shaped southern Thailand and northern Malaysia is possibly the most diverse in Southeast Asia. Langkasuka was an ancient Malay-speaking kingdom where a mixture of Buddhist, Bhramanic and Saora rites were practiced. The kingdom was based around the upper part of the Malay Peninsula and the lower part of the Thai Isthmus, covering the 'Deep South', northern parts of Peninsular Malaysia and Thailand's Andaman coast. The kingdom is mentioned in the writings of Buddhist monks from both China and Sri Lanka and was also illustrated on maps by medieval Arab sailors. The kingdom was a trading hub for both the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea and undoubtedly absorbed influences from the Middle East, the Indian sub-continent and China. It is unknown why or when Langkasuka disappeared, yet no references to the kingdom can be found after 1300. Islam was introduced to the area by Arab merchants around 1100, and slowly spread across the Malay Archipelago thereafter. 'Patani' (Malay spelling for the historical kingdom) was established as an independent polity sometime between 1200 and 1350. Little is known about the establishment and early development of Patani; competing myths exist regarding these early years and are maintained by locals in the 'Deep South', yet it is believed that the kingdom was founded as a Mahayana Buddhist polity.[ii] Large numbers of Chinese traders and pirates started to arrive in the area from about 1400 onwards, establishing trading bases along the east coast of modern-day Thailand and Peninsular Malaysia. During the same period, the Siamese started to extend their empire further south over the sultanates of the Malay Peninsula. The Malay sultanates remained autonomous, yet paid tribute to the Siamese and provided them with soldiers for their wars against the Burmese.[iii]

Under Thai suzerainty, Patani developed as a major east coast trading port and center of Islamic learning. Trade with the Indian sub-continent greatly increased after the sacking of Malacca in 1511.[iv] Muslims from different parts of Southeast Asia often visited Patani before embarking on their Hajj. A relatively large number of Portuguese and Dutch traders also settled in Patani during this period. The reign of the four queens (1584 - 1651) is referred to as the 'Golden Age' of Patani: a time of development, prosperity and prestige for the small coastal sultanate; yet during this period, hostilities increased with neighbouring Malay sultanates. This era is fondly remembered by Malay-Muslim nationalists, yet the essential role played by Chinese traders in developing Patani must also be taken into account. {jathumbnailoff}

A Buddhist monk collects morning alms under armed military protection in the southern Thai city of Pattani. Monks have been the target of insurgents with many being injured and killed by roadside bombs, or IEDs. Some have even been beheaded

A Buddhist monk collects morning alms under armed military protection in the southern Thai city of Pattani. Monks have been the target of insurgents with many being injured and killed by roadside bombs, or IEDs. Some have even been beheaded

Growing Dutch economic dominance of the Malay Archipelago coupled with Siam's attempt at strengthening its rule over the Malay sultanates led to a decline in Patani's influence in the region from about 1700 onwards. The final blows to Patani's prestige came in 1786, when Siamese forces sacked Pattani town and then in 1809 when Patani came under the control of the court of Songkhla, a vassal of Siam. The area that made up the former Sultanate of Patani was split in half with the Anglo-Siamese treaty of 1909, which allowed Siam to hold on to half of the former Sultanate (which was later divided into Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat) while the rest of the sultanate became part of British Malaya.[v]

The assimilation ('Thaification') of the Malay-Muslim majority provinces was effectively started after the 1932 coup, but was intensified under the ultra-nationalist military-government of Field Marshall Phibun (1938 - 1944). Thai-Buddhists were settled in the three provinces and the Thai language was assertively promoted while the Malay language and way of dress were strongly discouraged by the Thai state. To maintain control over the Malay-Muslim population, local elites were replaced by Thai-Buddhists from Bangkok and the upper-South, a process referred to by some academics as 'internal colonialism'.[vi] The process of Thaification was continued after the monarchy was re-installed after the Second World War.

The aftermath of a massive car bombing litters the street in the southern Thai border town of Sungai Golok, The huge explosion left 6 people dead, including a prominent local journalist

The aftermath of a massive car bombing litters the street in the southern Thai border town of Sungai Golok, The huge explosion left 6 people dead, including a prominent local journalist

Resistance to Thaification began in the 1930s and intensified during the Phibun era. In 1947, Haji Sulong, a local Malay-Muslim nationalist, issued his 'seven demands' outlining a new system of governance for the 'Deep South', which advocated autonomy for the region and greater participation and representation for the region's Malay-Muslim population. Sulong's 'demands' were moderate in nature, yet even today they are seen by many as 'separatist' and as a threat to the 'unity' of the Thai state. Although often represented as a militant (by both Thai and Malay-Muslim nationalists), Sulong was a pious Muslim who spent much of his life studying and teaching in Mecca. The murder of Sulong and his brother by Thai authorities in January 1948 lead to widespread unrest, most notably the 'Dusun Nyor Uprising'. During the uprising, large numbers of local villagers in Narathiwat fought against Thai security forces. The large death-toll and the widespread destruction during the uprising has led to the event attaining a kind of mythical status for Malay-Muslim nationalists. The disturbances that followed Sulong's murder were brutally put down by the state, yet more violence was to follow in 1957, which was again quashed by state security forces.[vii]

The insurgency led by the Patani United Liberation Organisation (PULO) (1974 – 1988) came to a close after Thai security forces had effectively infiltrated the organisation and had beaten the militants into a stalemate after severely weakening or isolating the different insurgent groups. Yet it was a number of proposals put forward by minister Chavalit Yongchaiyudh that helped win the confidence of both militants and Malay-Muslim elites; such as offering a general amnesty for militants, increasing economic assistance for the South and creating the Southern Border Provinces Administrative Centre (SBPAC), a new body for administering the border region. This new deal for the 'Deep South' helped to maintain stability in the region for nearly a decade and a half. The infiltration of PULO and smaller groups by Thai military intelligence put the state in a position where it could both monitor and control the activities of known separatists,[viii] yet there were a number of unexplained arson attacks and shootings in the 'Deep South' between 1999 and 2004, which were dismissed at the time as 'banditry'.[ix]

In the early hours of 4 January 2004, a team of unidentified gunmen attacked a military installation in Cho Airong district, Narathiwat. All four soldiers guarding the base were killed and over one hundred weapons were stolen. The raid was followed by the murder of a 64-year-old Buddhist monk (also in Narathiwat) a few days later. The daring raid and the murder of an unarmed, elderly monk were dismissed by the government as 'the work of bandits', yet the escalating number of attacks in early-2004, which included drive-by shootings, roadside bombings, the burning of schools and coordinated attacks on government buildings, indicated that a major insurgency was under way, one which caught the Thai state completely by surprise. The military's response to the attacks was both unprofessional and counter-productive; sweeping military raids on Malay-Muslim villages, harassment of locals and a general lack of knowledge about the 'Deep South', led to security forces alienating many Malay-Muslims during the early years of the conflict. The situation was made worse by a power struggle between the police and military, differing political affiliations amongst the security forces and a belief that local police were involved in a widespread cross-border smuggling racket.

24-year-old Kariya Duramae, a Malay-Muslim deputy village head man, lies dead in the road after he was gunned down on his way home by suspected Islamic insurgents

24-year-old Kariya Duramae, a Malay-Muslim deputy village head man, lies dead in the road after he was gunned down on his way home by suspected Islamic insurgents

Changes made to the post-1988 security structure by Thaksin Shinawatra no doubt helped destabilise the situation in the 'Deep South'. Abolishing the SBPAC and the Civilian-Police-Military Task Force 43 (CPM - 43) and placing the police in charge of security led to increased rivalry between the police and military, culminating in the murder of over twenty military informants (former insurgents) by the police under the guise of the 'War on Drugs' in 2003. This link between the military and the insurgents was essential for maintaining communication between the state and separatists and also for monitoring any developments within the movement. The police put in charge of security were mainly Thaksin supporters from Bangkok or from the upper south who were unfamiliar with the local culture.[x]

The response of the Thaksin government to the violence in early 2004 further exacerbated the situation. A heavy-handed crackdown led to an increase in the level of violence with the most notable incidents happening in 2004 at the Krue Se Mosque (Pattani) and at a demonstration in Tak Bai (Narathiwat). Insurgents used the 500-year-old Krue Se Mosque for shelter after carrying out multiple attacks on military and police installations on 28 April. Both insurgents and local men who happened to be praying there at the time; all died inside the Mosque after a shoot-out with security forces. The Mosque itself, a symbol of Patani's 'golden era', was badly damaged by a tank shell during the siege. The police response to the demonstration in Tak Bai, where over seventy unarmed men died of asphyxiation whilst being transported to a military base for interrogation, also greatly undermined confidence in the government.[xi]

Photographs of the aftermath of violence line the wall of a Buddhist charity in the southern Thai city of Pattani. The charities collect the bodies and then take them to the morgue so they can be claimed by their relatives

Photographs of the aftermath of violence line the wall of a Buddhist charity in the southern Thai city of Pattani. The charities collect the bodies and then take them to the morgue so they can be claimed by their relatives

In July 2005, the Thaksin government introduced emergency powers to deal with the crisis, giving the police and military wide-ranging powers to arrest and detain suspected insurgents, which led to increased feelings of victimisation amongst Malay-Muslims. The government also established 'village defence units' (paramilitary organizations) in 2005, which were greatly expanded after 2007. The violence continued unabated throughout 2005 and 2006 with the majority of victims being Malay-Muslims. Yet the most widely-reported attacks have been the beheading of soldiers and Buddhist monks and the killings of school teachers and temple boys by insurgents.

The Thaksin government attempted to implement a peace process in 2005. The National Reconciliation Commission (NRC) involved discussions with rebel leaders living in exile using former Malaysian prime-minister Mahathir as a mediator. The talks were ineffective, as the exiled leadership seemed to have little contact with the combatants on the ground and very little was put forward by the Thai government. Thaksin's accusation that the Malaysian government were supporting the insurgents (although no evidence existed to support such a claim) also served to undermine the work of the commission, which, according to Senator Anusart Suwanmongkol, was widely seen as irrelevant by most Thai-Buddhists and Malay-Muslims.[xii]

The Thaksin government was toppled by a coup in September 2006. The coup-leader General Sonthi Boonyaratglin advocated a 'hearts and minds' campaign towards the 'Deep South' and announced the re-establishment of the SBPAC and CPM – 43. After the coup, troop levels were boosted in the South to 60,000, which were supported by newly recruited Tahaan Phran (border-based rangers) units, who proved to be very unpopular with Malay-Muslim locals.[xiii] Although the government had adopted a more conciliatory approach, there was a sharp increase in violence, with over 1,000 more deaths between September 2006 and July 2007. An apology for the Tak Bai killings came in 2007, yet none of the soldiers involved were prosecuted.

Before the creation of village defence units in 2007, a representative for Human Rights Watch argued that the insurgents' strategy was "no longer to just empty villages of Buddhists, but whole districts".[xiv] Over 10% of Thai-Buddhists and Chinese-Thais left (sometimes abandoning) their homes between 2004 and 2007, although some have returned since 2008. The troop surge and the expansion of paramilitary units during 2007 led to the further militarisation of the south, yet also to a general decline in violence. In total, there were 410 separate bomb attacks in 2007, making it the most violent year of the conflict so far. In comparison, there were 174 bomb attacks in 2008. The killing of Malay-Muslims working for the Thai state (regardless of occupation) by insurgents has continued, with many low-level politicians and administrators finding themselves in the crossfire: being accused by the government of not cooperating with state forces, while also being labeled 'collaborators' by insurgents and their sympathisers.

Muslim school children attend a morning flag raising ceremony in front of the burnt out remains of their classrooms. Suspected Islamic insurgents set fire to the school the night before

Muslim school children attend a morning flag raising ceremony in front of the burnt out remains of their classrooms. Suspected Islamic insurgents set fire to the school the night before

Another casualty of the conflict has been the Malay-Muslim political elite. When the violence escalated in 2004, the political elite, some of whom were allied to Thaksin's Thai-Rahk-Thai party, were quick to support the government in Bangkok and were viewed by many Malay-Muslims as being completely out of touch with what was happening on the ground. The Thai state attempted to integrate the region into the national political structure by integrating local elites into the Bangkok political establishment from the late-1980s onward. McCargo argues that from the time of the ceasefire in 1988 until the re-emergence of the insurgency in 2004, a distance had developed between the Malay-Muslim political elite and the common people of the three provinces.[xv] The position taken by elected representatives when the violence started in 2004 indicated where their loyalty lay and how detached they had become from the people they represented. It seems that Bangkok had overly-domesticated the Malay-Muslim political elite, to the detriment of both. The local political elite were seen as the local representatives of Bangkok and were in turn rejected by the population of the three provinces. Leading 'Deep South' politicians, such as Den Tohmeena and Wan Nor, both lost their seats in the 2005 elections, while accusations of separatism against Narathiwat-based Waemahadi Wae-dao helped him secure a seat during the same period. [xvi]

It is true that the upsurge in violence happened around the same time as the abolition of the SBPAC and the changeover of authority in the 'Deep South', yet to view this as the primary cause of the violence, as many analysts have done, would be to overstate one of many contributing factors. I argue that the necessary political, social, economic and historical fault-lines were already in place and that changes made to the delicate politico-security apparatus for the 'Deep South' during the Thaksin era were the catalyst for launching a new insurgency that could enjoy some level of popular support. Yet, the availability of young men passionate or deluded enough to join an insurgency could not simply be the result of social or economic factors. The aforementioned 'Patani' ethno-nationalist historical narrative, maintained and promoted by activists (and sometimes educators), is another factor that is commonly downplayed by analysts when explaining the causes of the continuing violence in the 'Deep South'.[xvii] {jathumbnailoff}

Many different theories were put forward during the early years of the conflict, regarding the insurgents' motivations, their organisational structure and whether they were connected to militant groups from the former-conflict (1974 – 1988). Claims that insurgent cells 'spring up naturally' or that militants from the last conflict are guiding the new movement with a different structure have not been supported by any substantial evidence. The possibility that the new generation of insurgents is entirely unrelated to older insurgents, or that the different groups might behave in a more competitive than cooperative manner with each other, is often avoided. It is widely believed that Barisan Revolusi Nasional – Coordinate (BRN-C) are behind the majority of the attacks, yet older, smaller groups such as PULO, BNPP and possibly GMIP are also involved. According to Sasha Helbardt, PULO have between 30 and 60 fighters on the ground, while GMIP are estimated to have about 40 fighters, many of whom are involved in the local narcotics trade.[xviii] An organisation named Bersatu claims to represent all of the above-mentioned militant groups. Yet such claims have been disputed. {jathumbnailoff}

The conclusions arrived at by Duncan McCargo and Sasha Helbardt, who both carried out fieldwork in the 'Deep South' in 2006/2007 and 2009/2010 (respectively) are illuminating, unsettling and at times, bizarre. Sasha Helbardt, who spent time with both members of the Thai military and BRN-C, concluded that BRN-C has a centralised vertical command-and-control network, yet the foot-soldiers of the movement are organised into cells to maintain secrecy. Informants also stated that BRN-C have no substantial links to older insurgent groups. Helbardt observed that training and indoctrination are strongly emphasised in order to motivate recruits and that insurgents come from different socio-economic backgrounds and tend to adhere to different ideologies: some are nationalists, some are 'Islamists' and some are opportunists. Interestingly, he observed how recruits tend to develop an extreme sense of empowerment from being part of the movement.[xix] Insurgents informed Helbardt that they would eventually triumph over a Thai army they see as corrupt, lazy and unethical and that rumour spreading and misinformation were a deliberate tactic used to confuse the authorities and motivate common Malay-Muslims.[xx] Helbardt also gives examples of how BRN-C recruiters (both male and female) tend to approach the family and friends of victims, offering them 'a chance for revenge'.[xxi]

Members of 44 Ranger Battalion take a break from their training at an army camp outside the southern Thai town of Narathiwat. The Rangers are a government trained and armed unit made up entirely of volunteers. There are currently more than 65,000 members of the Thai security forces stationed in the three southern most provinces of Pattani, Narathiwat, and Yala

Members of 44 Ranger Battalion take a break from their training at an army camp outside the southern Thai town of Narathiwat. The Rangers are a government trained and armed unit made up entirely of volunteers. There are currently more than 65,000 members of the Thai security forces stationed in the three southern most provinces of Pattani, Narathiwat, and Yala

In interviews with young men who participated in attacks in 2004, Duncan McCargo noted how certain insurgents maintained superstitious practices, such as pouring 'magic sand' on roads in an attempt to damage the wheels of military vehicles, drinking 'holy water', and chanting phrases in Arabic to make themselves bulletproof whilst preparing for an attack. Although this might seem preposterous to many, McCargo argues that belief in magic is widespread in the Malay-speaking world.[xxii]

The connection between militants and the Islamic education system in the 'Deep South' is possibly the most sensitive issue related to the current violence in the 'Deep South'; it is an under-researched and highly sensitive topic that has only really been mentioned in passing by analysts. Yet numerous links between certain Pondok (Islamic schools), Tadika (Islamic schools for children), insurgents and those teaching a certain interpretation of 'Patani' history exist. What is more worrying is that certain Ustadz (Pondok teachers) have been directly involved in insurgent activities. Three Ustadz were involved in the coordinated attacks of 28 April 2004. Two of them, Zakariya Yuso and Sama-ae Lateh, were killed inside the Krue Ze Mosque, while the enigmatic 'Ustadz Soh', the supposed ringleader of the attacks, has subsequently disappeared.[xxiii] Certain nationalist leaders have also been involved in the Islamic education system at a higher level, such as Haji Abdul Karim bin Hasan (a well-known insurgent) who worked as a Tok Guru (Headmaster) at a Pondok in Ruso district, Narathiwat, while Haji Sulong both owned and ran a Pondok in Yala. In his doctoral thesis, Sasha Helbardt includes photographs of drawings from Tadika students, illustrating men shooting at cars and helicopters with machine guns and rockets.[xxiv] Mark Askew notes how documents related to the Dewan Pembabasan Patani or the Patani Liberation Council were seized by the military during a raid on an Ustadz's home in rural Narathiwat in 2005.[xxv]

The number of active fighters involved in the insurgency is another matter of dispute. Estimates have varied in recent years. In mid-2008, one high-ranking military source in ISOC Forward Command stated that there remained about 300 active armed insurgents (with a further 3,000 trained but inactive), with approximately 30,000 supporters, and up to 40 leaders; yet far greater numbers have been put forward by both the Thai state and by analysts.[xxvi] The northern 25% of Yala has been the most intensely affected by violence, yet large parts of Narathiwat and the southern half of Yala have hardly been affected at all. The most notable exception is Betong, a prosperous, mountainous district, bordering Malaysia, which has not experienced any substantial violence since 2004. Betong has developed due to cross-border trade with Malaysia and is known as a prostitution hotspot and a centre for cigarette smuggling. According to the daughter of a property developer from Betong, local Chinese-Thai elders pay insurgents not to carry out attacks within the district. Yet such claims and theories are common in the 'Deep South', as the widespread unexplained violence creates ample opportunity for conspiracy and speculation.[xxvii]

Members of a village defense force unit respond to an attack near their village. These units are trained and armed by the Thai Army. They have in the past been accused of human rights violations in the Deep South

Members of a village defense force unit respond to an attack near their village. These units are trained and armed by the Thai Army. They have in the past been accused of human rights violations in the Deep South

On repeated occasions, Malay-Muslims explained to me that the Thai military was prolonging (or had even created) the conflict as a means to receive more funding and to create opportunities for officers to advance their careers. When I enquired about individual incidents soon after they had happened, many Malay-Muslims would inform me that the army had been responsible. Such reasoning can be explained by a certain view that some people in the 'Deep South' have of their own community: that one of their people would not be capable of such a heinous act and that it must have been done by an outsider or by some external force. Yet such theories contain an element of truth. Security forces have carried out numerous extra-judicial killings since 2004, with the bodies of many of the victims having never been found.[xxviii] A military intelligence officer justified the policy to me, explaining that "the courts do not work... There is no evidence, no witnesses... We know who most of these people are and where they are but the locals will not cooperate." The same military intelligence officer explained how members of the security forces sometimes dress up in Malay clothing during covert-operations. He argued that such behaviour was justified as insurgents have sometimes dressed up as members of the security forces or as Muslim women when carrying out attacks in broad daylight.[xxix] A political scientist at PSU Pattani explained how leaflets, supposedly from insurgents, have often been created by the security forces to incite Thai-Buddhists to take up arms and join village defence units.

Both Malay-Muslims and Thai-Buddhists have willingly joined state-sponsored village defence units since their creation in 2004. The program was greatly expanded in 2007/2008 and has led to an overall decline in violence. The large number of locals joining paramilitary groups illustrates the siege mentality of many Thai-Buddhists and the climate of fear that exists in rural areas. It is common for insurgents to be referred to as "ghosts" by members of village defence units due to the transient nature of their attacks.[xxx] As expected, the widespread arming of villagers in an already violent borderland has created an enabling environment for individuals or certain interest groups to settle old scores and deal with 'problems' under the guise of defending their village or supporting the Thai state in its fight against separatism.

Approximately 100,000 civilians have joined paramilitary groups in the 'Deep South' since 2004,[xxxi] with the largest paramilitary group being the Chor Ror Bor (approximately 50,000 members). The Chor Ror Bor are provided with shotguns and given basic weapons training by security forces, although they are authorised to buy more advanced firearms. A more formal volunteer group called the Or Sor, whose origins can be traced back to the anti-communist insurgency of the 1970s, is smaller and tends to be targeted by insurgents more often than other paramilitary groups.[xxxii] The most controversial group has been the Or Ror Bor, a strictly Thai-Buddhist paramilitary group with approximately 25,000 members supported by the Royal Aide de Camp Department of the Thai Ministry of Defence. The Or Ror Bor is funded by the monarchy and its supporters and tends to be better trained and more organised than the Chor Ror Bor. Such royal-patronage has benefitted the organisation – for example there has been very little coverage in the mainstream Thai media of the murder of ten unarmed Muslims at the Al-Furqon mosque in Narathiwat (June, 2009) by members of the Or Ror Bor; neither has there been prosecution of any of the individuals involved. An informant I spoke to in Pattani explained that Thai-Buddhist villagers have been recruited by the Or Ror Bor as certain authorities were worried about the mass migration of Thai-Buddhists during the early years of the conflict.[xxxiii] A clandestine group Ruam Thai (United Thais) has been involved in the assassination of numerous suspected insurgents and also Malay-Muslim villagers as retaliation for attacks on Thai-Buddhists. The organisation was originally led by Colonel Phitak Ladkaew, a Yala-based policeman who has since been transferred to the upper-south. According to Michael Jerryson, the organisation has approximately 6,000 members, 200 of whom are Muslims.[xxxiv]

Narathiwat, Thailand. Village defense volunteers pray after completing a 14-day training course with the Royal Thai Military. During that time they were taught reconnaissance, information warfare, and how to patrol with a vehicle. The course finished with a live-fire exercise

Narathiwat, Thailand. Village defense volunteers pray after completing a 14-day training course with the Royal Thai Military. During that time they were taught reconnaissance, information warfare, and how to patrol with a vehicle. The course finished with a live-fire exercise

Killings of monks and temple-boys and attacks on Wat (Buddhist Temple Compounds) have been ongoing since 2004. Since then, soldiers and police have been stationed inside and nearby Wat; lack of accommodation for soldiers has been cited as an official reason. Buddhist villagers who fled their homes in the early years of the conflict have often found refuge at their local Wat. Before the conflict, Malay-Muslims sometimes visited their local Wat to buy medicine, watch Silat (martial arts performances), celebrate the Queen's birthday or (according to Michael Jerryson) to ask monks to 'de-hex' something for them. Yet such an association between security forces and Wat has no doubt affected how Malay-Muslims view the Sangha (Buddhist community and hierarchy) and visits from Malay-Muslims to Wat tend to be unheard of in recent years. Yet what is more worrying is the practice of soldiers becoming monks or monks being armed to defend themselves and their Wat.[xxxv] Officially, a Buddhist monk cannot carry arms, yet numbers have greatly increased in recent years with ordination ceremonies often being held on national holidays, such as the Queen's birthday.[xxxvi] One must also take into account the nationalist-royalist fervor that has swept Thailand in recent years, due to the royal succession crisis and the substantial challenge posed to the Thai establishment by the 'Red Shirt' movement. Overall, the militarisation of Wat has been a contentious issue. As Duncan McCargo observed, many monks are unhappy with their Wat being used as a military base and have stated that they are not on good terms with soldiers.[xxxvii]

The conflict, as already stated, has been under-reported by major media outlets, but as Mark Askew bluntly states, "this conflict has attracted its fair share of parachute journalism and superficial reportage by instant-experts, single-issue rights advocates, wide-eyed postgraduate researchers and assorted cranks. Many of them have been ensnared by local 'fixers' with their own agendas."[xxxviii] In every conflict, there is a conflict of narratives or a conflict over who determines the dominant narrative. The media and the world of academia often become tools in a propaganda war between warring parties, with each trying to determine the 'meaning' of the conflict, or which of the warring parties is the aggressor.

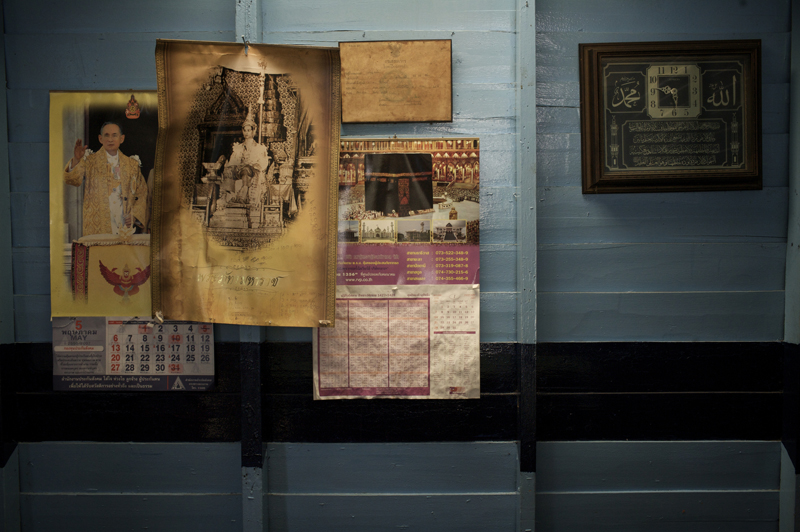

A poster of the revered King of Thailand, King Bhumibol Adulyadej, hangs next to Islamic text from the Koran in a tea shop in the southern Thai town of Narathiwat

A poster of the revered King of Thailand, King Bhumibol Adulyadej, hangs next to Islamic text from the Koran in a tea shop in the southern Thai town of Narathiwat

In June 2011, a young Malay-Muslim man I know gave a presentation at PSU Pattani titled 'Singapore'. He spoke of his respect for the culture of innovation in Singapore and how a visit there had made a big impression on him. What was most striking about his presentation was the photo he used for his desktop wallpaper: A photo of him and his friends in paramilitary uniform posing in a marketplace in a village in Pattani province. After the presentation, I asked him about his involvement with the Chor Ror Bor; he explained that, "it can be very dangerous sometimes... there are a lot of strange people around... people get shot for no reason... I want to make sure that my family is safe, sometimes naeoruam (insurgents) shoot the wrong person."[xxxix] The mainstream media in Thailand, Malay-Muslim spokespeople and most foreign analysts all tend to ignore the inconvenient truth that the number of young Muslim men joining paramilitary groups is far greater than the number joining or supporting the insurgency. The vast majority of both Chor Ror Bor [xl] and Or Sor [xli] members are Malay-Muslims.

How does one account for this huge level of 'collaboration' with the Thai state? In a survey carried out in 2010, Robert Albritton found that 84.4% of people identified as 'Malay' and 94.1% of those identified as 'Muslim' indicated that they were 'proud to be a citizen of Thailand' and over two-thirds of 'Muslims' stated that if needed, they would fight for Thailand in a war with a neighboring state.[xlii] Taking into account that people might have been afraid to voice their opinions, the figures are startlingly high. Albritton concluded that "the analysis of data obtained from respondents in southern Thailand presents a picture at odds with much of the conventional wisdom about sentiments and society in the region."[xliii] In a Deep South Watch poll from 2009, insurgency-related violence was voted the third biggest concern for residents of the 'Deep South' after unemployment and drug-abuse. The same poll found that 23.6% of participants considered unequal treatment/discrimination as the main reason for the ongoing conflict, while another 23% simply blamed insurgent groups. Interestingly, 8.5% of participants cited "lack of education among youth and overpopulation resulting from large Muslim families" as the cause of the violence.[xliv]

A young boy holds a poster of the revered King of Thailand, King Bhumibol Adulyadej, during a children's day parade

A young boy holds a poster of the revered King of Thailand, King Bhumibol Adulyadej, during a children's day parade

This issue of Malay-Muslim 'identity' has been a contentious topic since the violence began in 2004. In his doctoral thesis, published in 2011, Anusorn Unno describes the complicated overlapping loyalties that are held by many Malay-Muslims in the 'Deep South', and how such loyalties have been strengthened since the outbreak of violence in 2004. Unno describes how the ideology of the Thai state has been reinforced by various state agencies as a means to draw loyalty from local residents in response to pressure from insurgents.[xlv] The role of the Thai monarchy should not be downplayed, as it may be the only major state agency that many Malay-Muslims harbor little or no resentment towards. The view that the King is outside of (or above) politics, the King's charity works, his criticism of state-agencies (including the police) and the conditioning process that Thai children experience through the media and the state education system all help to maintain the monarchy's image as virtuous, benevolent and just. It could be argued that the conflict has opened up new opportunities for the monarchy to express itself to the average Malay-Muslim. Throughout the 'Deep South', one can see portraits of the King hanging on the wall of nearly every restaurant, office or shop, often placed beside a picture of Mecca or an excerpt from the Koran. Unno describes the many ways in which Malay-Muslims in a small village in Narathiwat engage with the Thai state without compromising their beliefs or identity, and how locals use their loyalty towards the King as leverage for dealing with agents of the Thai state: "As the patron of all religions and the ruler who impartially reigns over his subjects, the king provides a possibility for local residents to pay allegiance to different forms of sovereignty."[xlvi] In other words, paying tribute to the monarchy gives locals the opportunity to feel part of the Thai state without paying tribute to local officials who they may see as their oppressors. One must consider how this conflict would have evolved if Thailand was governed without a monarchy.

Another issue concerning identity is the use of the term 'Thai-Muslim' (often used in the media) to describe Malay-speaking Muslims from the 'Deep South'. The term 'Thai-Muslim' indicates a denial of difference or 'otherness' and is rarely used by Malay-Muslims from the 'Deep South' as a term to identify themselves.[xlvii] Yet more than 20% of Muslims in Thailand (who live in Thailand's Upper South) speak Thai as their first language, thus identifying themselves as 'Thai-Muslim'. Patrick Jory draws attention to the fact that the million or so Thai-speaking Muslims from outside of the 'Deep South' have not shown much solidarity with their co-religionists since the recent conflict began, and tend to have little interest concerning current events in the 'Deep South'.[xlviii]

Muslim school children learn Arabic at a privately funded Islamic school in the southern Thai town of Narathiwat

Muslim school children learn Arabic at a privately funded Islamic school in the southern Thai town of Narathiwat

It is a common belief amongst both Thai-Buddhists and foreign analysts that Malay-Muslims from the 'Deep South' feel some type of affinity with Malaysia or ethnic-Malays from Malaysia. Such an assumption is based on the fact that a lot of Malay-Muslims from the 'Deep South' work in Malaysia, speak a dialect of the same language, etc. During her fieldwork in Sugnai-Kolok (Narathiwat), anthropologist Michiko Tsuneda observed the antipathy that many Malay-Muslims from the 'Deep South' feel toward Malaysia and vice versa. Tsuneda concluded after dozens of interviews with Narathiwat locals living in Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur and Kelantan that most men choosing to leave the 'Deep South' preferred to work in Bangkok than Kuala Lumpur. She also describes the arrogant and discriminatory attitude of many Malaysians towards Malay-Muslims from Southern Thailand who work in Malaysia.[xlix] Although locals acknowledge their shared history and often have family living in both states, Tsuneda describes the psychological boundary that exists between the inhabitants on either side of the border: "The boundary between Thailand and Malaysia is demarcated not only by the state, but also by the imaginations, desires for, and denials of what lies beyond the national border that hves developed among the residents in the communities along the border over the years."[l]

Thailand's 'Deep South' has a long history of contact with other cultures and centres of power. Over the last century, different aspects of Thai culture have been imposed on the inhabitants of the 'Deep South', and more recently, the internet has provided greater access to Korean, Japanese and Western culture, as well as 'reformist' ideas from the Middle East. Like certain other colonised or post-colonial groups, many Malay-Muslims maintain a type of dual-identity, that of being both Thai and Malay-Muslim. Christopher Joll argues that Malay-Muslims have adapted different Thai customs and norms to conform to Malay or Islamic principles.[li] Such adaption is by no means unusual, and maintaining a dual identity is not seen as contradictory or problematic for most of the locals that I spoke with and observed during my nine months in Pattani. Yet, undoubtedly, certain individuals suffer from a type of identity crisis, a feeling of not being fully Thai or not being as 'Malay' as their kin in Malaysia, a feeling of incompleteness or of a paradise lost. Such feelings are made more intense by the potent ethno-nationalist historical narrative that draws on periods of glory and certain tragic or humiliating events of the past to mobilize and motivate disillusioned or directionless youth to take up arms and oppose the state and create a new 'Patani'.

Spending time with young people in Pattani gave me a chance to hear about everyday life in the villages and small towns of the 'Deep South'. Students at PSU spoke with pride about where they came from and about the local people they knew and respected. Yet I also heard stories of pointless feuds between neighbours and families, unemployed young men with too much time on their hands, widespread unemployment and lack of opportunities, a chronic drug problem, endless corruption and cronyism and a political/bureaucratic elite who were too far removed from the lives of ordinary people to understand their problems. Overall, there existed a general feeling of neglect by the state and a lack of inclusion in affairs that affect the local population, but by no means a deep or widespread hostility towards the state. Police I spoke to told me of the widespread drug abuse in the 'Deep South', stating that cheap homemade amphetamines such as see koon roi (four by one hundred) were a major cause of disruption and crime in the region. Yet, nearly everyone I spoke to, whether local Malay-Muslims or members of the security forces, maintained a stoic attitude towards their lives and towards the challenges that faced the region. Soldiers I spoke to were open to (or sometimes even eager for) a peaceful resolution to the conflict, as were Malay-Muslims, many of who seemed confused by the motivations of the insurgents.

Som runs a small café with his wife and daughter in Pattani town. He is a hospitable man who covers the walls of his café with toys that he has collected since he was a boy. Although he is a Thai-Buddhist, the majority of his customers are Malay-Muslims with whom he maintains a good relationship. Som keeps two firearms: one underneath the counter of his café and the other in his car. He also has a collection of gun magazines beside his cash register. He told me that it was unwise not to have a gun in Pattani, as there were a lot of kon rai (bad people) around. I was initially surprised by his suggestion that it was safer to arm oneself, rather than to be unarmed. Yet after a few months living in the 'Deep South', I realised that this was the norm. Another evening, after dinner with some local Thai-Buddhist men in Pattani, another local small business-owner showed me a small assault rifle that he kept in his bedroom. He dismantled the small, toy-like AK47 and then put it back together and loaded it. He explained that he didn't trust the local khek (racist term for Muslims) and described them as pae (goats). A few weeks earlier, a nearby restaurant owner showed me his wounds where he had been shot by a motorbike rider in 2008. Interestingly, he claimed that he did not know who had shot him or why. He believed that it was a case of mistaken identity. What is striking is that all three of these small-business owners lived within a five minute walk of my apartment in what was considered the safest part of Pattani.

A Thai border police unit displays weapons and drugs found when they raided a home used by suspected Islamic insurgents. Thai authorities have long believed that drugs are used to help fund their ongoing campaign of violence

A Thai border police unit displays weapons and drugs found when they raided a home used by suspected Islamic insurgents. Thai authorities have long believed that drugs are used to help fund their ongoing campaign of violence

Violent crime and widespread corruption have been endemic in the region long before the outbreak of violence in 2004. Writing in 2003, Alexander Horstmann listed the various activities that constitute the black economy of the 'Deep South' and how such a system is maintained by state officials: "Illegal border transactions include illegal logging, especially in Yala, the methamphetamine trade, human trafficking, and smuggling (smuggling of small arms, logs, foodstuffs, petrol, and consumer products). The border economy is sustained by coalitions of corrupt officials, the local mafia, the military, the Border Patrol Police, and the Royal Thai Police. The illegal border economy is a multimillion dollar business, which provides large rents for complicit officials.'[lii] The most striking aspect of this culture of smuggling in the 'Deep South' is the lack of discretion of the individuals involved. One simply has to look at the widespread availability of cheap, illegal petrol being sold on the street in Pattani, Yala or in smaller towns like Chana. It is a common belief amongst locals that high-ranking police officers are behind the smuggling and sale of bootleg fuel in the 'Deep South'.

A Thai sex worker from Udon Thani in Thailand's north hides her face while working at a bar in the southern Thai fishing port of Pattani. Her regular clients are Burmese fishermen on shore leave. The money that she earns she sends back to her parents in Udon Thani

A Thai sex worker from Udon Thani in Thailand's north hides her face while working at a bar in the southern Thai fishing port of Pattani. Her regular clients are Burmese fishermen on shore leave. The money that she earns she sends back to her parents in Udon Thani

Links between insurgents and drug-smuggling have been suspected by police as narcotics have sometimes been found during weapons seizures. Yet the amount of crossover between criminals and insurgents is unknown. The porous border between the two countries has been beneficial to insurgents, smugglers and drug-dealers from both Thailand and Malaysia. The mass movement of people between the 'Deep South' and Kelantan province is impossible to monitor due to mass cross-border trade and the fact that approximately 300,000 Malay-Muslims from the 'Deep South' work in Malaysia, on a full-time basis, or seasonally.[liii]

Mark Askew argues that the term 'insurgency' is misused when describing the violence in the 'Deep South': "the English language term 'insurgency' is inadequate to define the totality of the violence. Something more than an 'insurgency' is going on in the current mix of violent events. Arguably, 'insurgency-centred turbulence', or 'insurgency-driven violence', there are now confusing overlaps between insurgents, competing local political groups and criminals. In addition to the agglomeration of criminal violence, there is also a generic type of conflict represented by the many killings among rival local politicians (mainly Muslim), which reflects the chronic violence prevalent in Thai society generally."[liv] Askew argues that the 2008 bombing of CS Hotel in Pattani was carried out by a rival political faction: "Evidence subsequently unearthed by police confirmed that the bombing was undertaken by insurgent bomb-makers, but information about the vehicles used in the attack (and a simultaneous, but failed, car bomb attack in Yala) pointed to the involvement of a prominent local Muslim politician suspected to have sought revenge against the hotel owner (a Senator affiliated to the Democrat Party) who had supported his political rival in a provincial election."[lv] Duncan McCargo notes how two well-known Narathiwat politicians, Kuheng Yawohasan and Nisoh Meuka were assassinated in 2005 and 2006, while Senator Fakhruddin Boto (also from Narathiwat) was shot and injured during the same year. The three attacks were carried out around the time of elections, yet the assumption that these three attacks were insurgency-driven remains.[lvi] At a press conference in late 2011, Lieutenant General Udomchai Thammasarojrat (Fourth Army region chief) stated that possibly only 20% of violent incidents in the south were committed by insurgents and that such violence was confined to specific areas within the three provinces.[lvii]

An AK-47 assault rifle rests on a chair outside the home of a government-backed militia

An AK-47 assault rifle rests on a chair outside the home of a government-backed militia

An unusually high number of killings have been carried out on rubber plantations in the 'Deep South'. Such killings tend to also be placed under the heading of 'insurgency'. Soldiers I spoke to in Pattani believed that people were taking advantage of the state of violence to settle old scores and get rid of competition over land. As one soldier stated, "one day this will all be over... so now is a good time to buy land and make investments, especially as people are leaving their homes out of fear and property is cheap." His captain, a native of Yala, described the poor quality of land in the 'Deep South' and the prevalence of long-running disputes between neighbours over property.[lviii] Multiple bomb attacks in Sugnai-Kolok (Narathiwat) in September 2011 were reported as insurgency-related, yet further investigation led police to believe that the attacks were carried out by drug-traffickers[lix] as revenge for a large drugs seizure a few weeks before.[lx]

The widespread crime prevalent in the 'Deep South' does not exist as a result of the current political violence, neither is all of the violence politically-driven. One could argue that an enabling environment has developed, which gives opportunistic individuals the freedom to achieve their aims through violent means, whether they are drug-dealers, feuding politicians or those engaged in turf-wars or local feuds. The policy of silence employed by insurgents has created an environment where such violent acts become lost somewhere in the narrative of the conflict. {jathumbnailoff}

22-year-old Wae Mohammed Johan displays a portrait of his father, Assan Tea Rook, a Policeman and Muslim, who was killed two years earlier in a shootout with suspected Islamic Insurgents in Sai Buri district, South Thailand. He now lives with his mother and sister in the "Widow Village" outside the Southern Thai town of Narathiwat

22-year-old Wae Mohammed Johan displays a portrait of his father, Assan Tea Rook, a Policeman and Muslim, who was killed two years earlier in a shootout with suspected Islamic Insurgents in Sai Buri district, South Thailand. He now lives with his mother and sister in the "Widow Village" outside the Southern Thai town of Narathiwat

Throughout 2010/2011, 'secret' negotiations between the Thai government and insurgents were mediated by a Swiss-based conflict resolution body. The Thai government was represented by General Chetta Thanajaro, while the different insurgent groups were represented by Kasturi Mahkota, a former insurgent from the 1974-1988 conflict and current president of PULO, who has been based in Sweden for over fifteen years. In 2010, Kasturi announced that PULO would act as the political wing for BRN-C and that this arrangement would be referred to as the 'Patani Malay Liberation Movement' (PMLM). Kasturi initially claimed to have control over 70% of fighters on the ground.[lxi]

Kamaria Awealoh sits with her youngest daughter who holds a portrait of her slain husband who was gunned down by suspected Islamic Insurgents two years before. She now lives in housing provided by the Thai Royal Family along with her four daughters

Kamaria Awealoh sits with her youngest daughter who holds a portrait of her slain husband who was gunned down by suspected Islamic Insurgents two years before. She now lives in housing provided by the Thai Royal Family along with her four daughters

Talks between PULO representatives and the Thai government were initially seen as hopeful by both the military and local analysts, yet very little was offered by Kasturi and much skepticism surrounded his role within the movement and PULO's effective level of control over active insurgents. Kasturi and other exiled members of PULO have been described by Marc Askew as "vocal but impotent has-beens",[lxii] ageing former-insurgents that have no "demonstrable organizational links" with more recently-formed insurgent groups.[lxiii] Kasturi's claims were never verified by BRN-C, which (along with the obvious differences between the tactics and rhetoric of the older generation of insurgents with newer organizations such as BRN-C) led to much doubt surrounding the legitimacy of PMLM. {jathumbnailoff}

The month long cease-fire in the summer of 2010 (10 June – 10 July) only took place in three of Narathiwat's districts and was seen by many as an admission of Kasturi's lack of influence over the greater insurgent movement. The fact that the ceasefire took place in only three out of thirty-six districts within the 'Deep South' raised many questions, especially as the three districts in question have never been particularly violent.[lxiv] The talks were temporarily put on hold after it became clear that Kasturi had very little control over insurgents on the ground, yet negotiations have since continued. The involvement of this 'old-guard' as a negotiator is an admission of confusion and weakness on the Thai side and also a testament to the ambition of certain people within the Malay-Muslim community. One could argue that this is an example of career-building, more so than peace-building. A full cease-fire for a whole province (or for all three provinces) would act as proof of PULO's influence and serve as a confidence-building measure for any future negotiations. According to Don Pathan, many militants are unwilling to negotiate because they are afraid of being assassinated.[lxv] Negotiations have also been undermined by accusations of drug-trafficking from both sides.[lxvi]

The daughter of slain Thai journalist Chalee Boonsawat cries as his body is taken from a local hospital to the morgue. Chalee was killed by a huge car bomb in the southern Thai town of Sungai Golok, along with five other people

The daughter of slain Thai journalist Chalee Boonsawat cries as his body is taken from a local hospital to the morgue. Chalee was killed by a huge car bomb in the southern Thai town of Sungai Golok, along with five other people

The devolution of power to a regional assembly or the creation of an autonomous region for the 'Deep South' has proven to be something of a taboo for the Thai political elite. Although the Thai constitution states that Thailand is an "indivisible kingdom", both Bangkok and Pattaya already have exceptional governance arrangements, and decentralisation is something being discussed for both the northwest and northeast of Thailand. Yet the discussion of autonomy for the 'Deep South' seems to be a psychological barrier for policymakers in Bangkok. There is a fear that any autonomy granted to a peripheral region may lead to the fragmentation of the country.

General Chavalit Yongchaiyudh, a former prime-minister and army commander, advocates a model he calls 'Mahanakorn Pattani' (originally titled 'Nakhon Pattani'), a local system of governance for the 'Deep South', similar to Bangkok's special arrangements. Chavalit maintains strong ties with local Malay-Muslim politicians and was the motivating force behind the 1988 amnesty for militants that helped bring the last conflict to an end. 'Mahanakorn Pattani' was promoted by certain members of the Pheua Thai party and supported by some local Malay-Muslim leaders, yet resistance to such ideas remains strong. The National Reconciliation Commission's (NRC) report, which was published in 2006, outlined a number of proposals that were impressive in nature, yet subsequent governments have failed to implement any meaningful changes. Neither autonomy nor devolution was discussed by the NRC.[lxvii] In 2006, the National Legislative Assembly (NLA) established a special committee to analyse violence and disturbances in the Southern Border region. In its report, the committee outlined severe miscarriages of justice by the local authorities as a cause of the continuing violence.[lxviii] The SBPAC was reinstalled by the military along with a new civilian-military authority after the 2006 coup, although the new SBPAC was put directly under the military's command. The Abhisit government, which came to power in 2008, promised reforms such as strengthening the SPBAC, creating a 'Southern Cabinet' to administer the South, judicial reforms, the localisation of security arrangements and also the provision of an economic stimulus package. Troop numbers were increased in 2008, yet none of the other proposals were implemented, with the exception of the economic stimulus package, yet most of the funding for the Southern Border Provinces goes to Songkhla and Saturn, and not the 'Deep South'.[lxix]

Compensation for victims (excluding government officials) of violence in the 'Deep South' has been recommended by the current Minister of Justice, Pracha Promnok. In February 2012, Pracha suggested that up to 7.5 million baht in compensation could be paid to victims extending back eight years to include both the 2004 Krue Ze Mosque and Tak Bai incidents, although those affected by both incidents have already received compensation.[lxx] Compensation payments are an effective way of 'winning hearts and minds', yet such payments would be far more effective after hostilities have ceased. What those affected by violence often yearn for more than compensation is the truth surrounding the death or disappearance of their loved ones. An inquiry, possibly based on South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, would be an effective way of dealing with past acts of violence if the conflict in the 'Deep South' were to be resolved. Such an inquiry might also help those who have been affected by insurgent violence deal with their feelings of loss and injustice.

Offering a full amnesty to insurgents would be a controversial, yet essential, element of any lasting peace deal for the 'Deep South'. Men who have killed temple boys, school teachers and elderly Buddhist monks would be released from prison and then 'reintegrated' into society. Considering the large number of attacks on civilian targets, such an amnesty would no doubt meet much opposition from victims of insurgent violence. A prototype amnesty program referred to as Tai Rom Yen is based at Inkhayut detention centre and military base in Pattani province. Inkhayut is bizarrely referred to as (without irony) "the resort" by military and political figures. As part of the reintegration process, local Islamic religious teachers have been invited to lecture detainees about how violence is prohibited in Islam.

A young Muslim man reads verses from the Koran whilst sitting over the grave of a loved one

A young Muslim man reads verses from the Koran whilst sitting over the grave of a loved one

The 'Deep South' is both historically and culturally different from the rest of Thailand. It could be argued that an exceptional system of governance is needed to administer such a region; namely, a system of autonomy, where Malay-Muslims (along with Thai-Buddhists and Chinese-Thais) would have control over their own affairs. Attempts by the Thai state to integrate the region have not been a complete failure. The integration of Islamic schools and the creation of provincial Islamic councils and a greater national Islamic council have no doubt created a feeling of greater-participation for many. Yet many attempts at integration by the Thai state have been aimed at increasing the power of the state and their ability to 'manage' the population, and not at improving the level of participation amongst the population in political affairs.

Since January 2004, nearly 5,000 people have been killed and over 8,000 injured in Thailand's 'Deep South'. A large percentage of this violence is insurgency-driven or insurgency-related, yet the region's long history of endemic criminality and disorder must also be taken into account. The Thai government has made changes to its mode of governance for the 'Deep South', yet such changes have been minor and of little consequence. The main barrier in the way of any peace process is the absence of any tangible representative for the insurgents. It seems that those leading the insurgency seem to find the current level of violence acceptable, as do possibly certain elements of the Thai government. The conflict has entered what William Zartmann calls a "bearable stalemate": a situation where the benefits of compromising are seemingly outweighed by the benefits of continuing to use physical force.[lxxi] It seems that such a situation shall remain as long as the violence stays confined to the peripheral, under-developed 'Deep South' and away from centres of administration or commerce, such as Bangkok or Phuket.

Thanks to Richard Humphries, Nobert Ropers at Berghof Peace-Support, Srisompob Jitpiromsri at Deep South Watch, Jason Johnson at Asia Times and Halil Rahman Basaran at Istanbul Sehir University for their time and consultation.

Gerard McDermott is a writer, researcher and photographer currently living in south-eastern Turkey. He is a graduate of both the National University of Ireland and of University of Ulster.

NOTES

[i] Upward, Jeff – Insurgency in Southern Thailand: The Cause of conflict and the Perception of Threat, 2006, (p13)

[ii] Tsuneda, Michiko – Navigating Life on the Border: Gender, Migration, and Identity in Malay Muslim Communities in Southern Thailand, 2009, (p100 – p108)

[iii] Bradley, Francis – Piracy, Smuggling, and Trade in the rise of Patani, 2008, (p30 – 42)

[iv] Tsuneda, Michiko – Navigating Life on the Border: Gender, Migration, and Identity in Malay Muslim Communities in Southern Thailand, 2009, (p100 – 108)

[v] Bradley, Francis – Piracy, Smuggling, and Trade in the rise of Patani, 2008, (p35 – 42)

[vi] Joll, Christopher – Muslim Merit-making in Thailand's Far-South, 2010, (p38)

[vii] Ockey, James – Individual imaginings: The religio-nationalist pilgrimages of Haji Sulong Abdulkadir al-Fatani, 2011, (p99 – p117)

[viii] Askew, Marc – Fighting with Ghosts: Querying Thailand's 'Southern Fire', 2010, (p134)

[ix] Storey, Ian – Ethnic Separatism in Southern Thailand: Kingdom Fraying at the Edge?, 2007, (p2)

[x] Askew, Marc – Review Article: Insurgency redux: Writings on Thailand's ongoing southern war, 2011, (p167)

[xi] McCargo, Duncan – Tearing Apart the Land: Islam and Legitimacy in Southern Thailand, 2008, (p108-p118)

[xii] McCargo, Duncan – The Politics of Buddhist identity in Thailand's deep south: The Demise of civil religion?, 2009, (p30)

[xiii] Jitpiromsri, Srisompob & McCargo, Duncan – The Southern Thai Conflict Six Years On: Insurgency, Not Just Crime, 2010, (p159)

[xiv] Human Rights Watch, 'No One Is Safe. Insurgent Attacks on Civilians in Thailand's Southern Border Provinces', August 2007

[xv] McCargo, Duncan – Tearing Apart the Land: Islam and Legitimacy in Southern Thailand, 2008, (p54 – 75)

[xvi] Ibid (p60 – 72)

[xvii] Helbardt, Sasha – Deciphering Southern Thailand's violence: organisation and insurgent practices of BRN – Coordinate, 2011, (p76 – 86)

[xviii] Ibid (p25)

[xix] Ibid (p181)

[xx] Ibid (p114 & p150)

[xxi] Ibid (p79)

[xxii] McCargo, Duncan – Tearing Apart the Land: Islam and Legitimacy in Southern Thailand, 2008 (p140 – 162)

[xxiii] Ibid (p132 – 155)

[xxiv] Helbardt, Sasha – Deciphering Southern Thailand's violence: organisation and insurgent practices of BRN – Coordinate, 2011 (p79)

[xxv] Askew, Marc – Fighting with Ghosts: Querying Thailand's "Southern Fire", 2010, (p153)

[xxvi] Ibid (p130)

[xxvii] Interview with Betong resident, Hat Yai, August 2011

[xxviii] McCargo, Duncan – Tearing Apart the Land: Islam and Legitimacy in Southern Thailand, 2008, (p99)

[xxix] Interview with Military Intelligence Officer, Pattani, August 2011

[xxx] De Borchgrave, Arnaud; Sanderson, Thomas & Gordon, David – Conflict, Community, and Criminality in Southeast Asia and Australia: Assessments from the Field, 2007, (p55)

[xxxi] McCartan, Brian – Religion, guns tear apart south Thailand, Asia Times, 2009

[xxxii] Whangni, Abdullah – Or Sor: Another soft target for the militants in the far South?, Isra News, 2011

[xxxiii] Interview with Military Intelligence Officer, Pattani, June 2011

[xxxiv] Jerryson, Michael – Buddhist Fury: Religion and Violence in Southern Thailand, 2011, (p141)

[xxxv] Jerryson, Michael – Appropriating a space for violence: State Buddhism in southern Thailand, 2009, (p34 - p47)

[xxxvi] Ibid (p53)

[xxxvii] McCargo, Duncan – The Politics of Buddhist identity in Thailand's deep south: The Demise of civil religion?, 2009, (p24)

[xxxviii] Askew, Marc – Review Article: Insurgency redux: Writings on Thailand's ongoing southern war, 2011, (p161 )

[xxxix] Interview with PSU Student, Pattani, June 2011

[xl] Sarosi, Diana & Sombutpoonsiri, Janjira – Rule By The Gun: Armed Civilians and Firearms Proliferation in Southern Thailand, 2009, (p21, p25)

[xli] McCargo, Duncan – Tearing Apart the Land: Islam and Legitimacy in Southern Thailand, 2008 (p122)

[xlii] Albritton, Robert – The Muslim South in the Context of the Thai Nation, 2010, (p79)

[xliii] Ibid (p85)

[xliv] Jitpiromsri, Srisompob – The Protracted Violence amidst the Unstable Political Situation after 2011 Elections, Deep South Watch, 2011

[xlv] Unno, Anusorn – 'We Love Mr. King': Exceptional Sovereignty, Submissive Subjectivity, and Mediated Agency in Islamic Southern Thailand, 2010, (p29)

[xlvi] Ibid (p312)

[xlvii] McCargo, Duncan – Co-optation and Resistance in Thailand's Muslim South: The Changing Role of Islamic Council Elections, 2010, (p92 - 107)

[xlviii] Jory, Patrick – From Melayu Pattani to Thai Muslim: The Spectre of Ethnic Identity in Southern Thailand, 2008, (p256/257)

[xlix] Tsuneda, Michiko – Navigating Life on the Border: Gender, Migration, and Identity in Malay Muslim Communities in Southern Thailand, 2009, (p245 – p246)

[l] Ibid (p120)

[li] Joll, Christopher – Muslim Merit-making in Thailand's Far-South, 2011, (p25 – 51)

[lii] Horstmann, Alexander – Violence, Subversion, and Creativity in the Thai–Malaysian Borderland, 2007, (p139)

[liii] Funston, John – Thailand's Southern Fires: The Malaysian Factor, 2008, (p57)

[liv] Askew, Marc – Fighting with Ghosts: Querying Thailand's 'Southern Fire', 2010, (p5)

[lv] Ibid (p6)

[lvi] McCargo, Duncan – Tearing Apart the Land: Islam and Legitimacy in Southern Thailand, 2008, (p73)

[lvii] Askew, Marc – Politics of proclamations in south Thailand, Asia Times, 2011

[lviii] Interview with soldiers, Pattani, October 2011

[lix] Sungai Kolok blasts claim sixth victim as reporter dies, Bangkok Post, Sept 2011

[lx] Thailand police say drug dealers behind bombings, CTV News, Sept 2011

[lxi] Davis, Anthony – Thai peace talks come to light , Asia Times, April 2011

[lxii] Askew, Marc – Review Article: Insurgency redux: Writings on Thailand's ongoing southern war, 2011, (p161)

[lxiii] Askew, Marc – Fighting with Ghosts: Querying Thailand's 'Southern Fire', 2010, (p13)

[lxiv] Johnson, Jason – Talk is Cheap in South Thailand, Asia Times, May 2011

[lxv] Pathan, Don – Can the old guard get peace talks going in the South? The Nation, April 2011

[lxvi] PULO calls on Thai authorities to stop making false allegations, The Nation, Sept 2011

[lxvii] McCargo, Duncan – Thailand's National Reconciliation Commission: a flawed response to the Southern Conflict, 2010, (p78 – 86)

[lxviii] Askew, Marc – Fighting with Ghosts: Querying Thailand's 'Southern Fire', 2010, (p137)

[lxix] Jitpiromsri, Srisompob & McCargo, Duncan – The Southern Thai Conflict Six Years On: Insurgency, Not Just Crime, 2010, (p172)

[lxx] Askew, Marc – Battle for credibility in a grubby war, Asia Times, February 2012

[lxxi] Zartmann, William & De Soto, Alvaro – Timing Mediation Initiatives, 2010, (p11 – p23)

All images (c) Richard Humphries.