The IRA

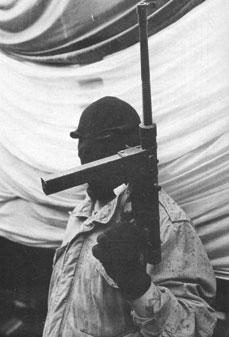

I Apocalypse AvertedAt 9.30 on the morning of Saturday, 19th April, this year, a car containing five armed and masked men, drew up outside the home of a farmer, not far from the South Armagh village of Crossmaglen. The men got out of the car and went into the house where the farmer and his family were just finishing breakfast. They demanded and got, the keys to his tipper lorry parked outside and while two of the men stayed with the farmer's family, the other three drove the lorry back where they had come from, across the Border.

Two miles across the Southern side of the Border, along the windy roads of county Monaghan, the lorry drove into a farmyard and stopped. The men got out and were joined by several others, who had been waiting nervously for them in a number of outbuildings. Over the next two hours the farmyard was a scene of intense activity as the men screwed into position on the back of the lorry, ten long mortar tubes. The tubes were then loaded with home made mortar bombs, each containing five lbs of commercial explosives, packed into beer gas cylinders.

The mortars were improvised IRA devices, called Mark 10's by British Army technical experts, who had learned to fear them since exactly a year before, when a shower of Mark 10's had devastated Newtonhamilton RUC barracks, killing a soldier in the process. After the complicated firing mechanism for the mortars had been set, the lorry was driven to Caulfield Place in Newry, about 100 yards from the town's RUC station and parked. Five minutes later, the first of the mortars went off. It fell short of its target and blasted a five foot hole in the police station wall. A second mortar followed, but exploded in mid-air, breaking the leg of a teenage boy and injuring 25 civilians and 2 RUC men.

None of the other mortars went off. It was an insane but calculated gamble by the Provisional IRA. If the mortars had fallen short, they would have ploughed into a row of terraced houses, killing and maiming dozens. If on the other hand the attempt had succeeded as planned, the mortars would have caused carnage inside the police station. Afterwards British Army bomb experts reckoned that up to 40 policemen and soldiers could have been killed. Almost enough, as one Army source put it, for the Provos, "to blast their way back to the negotiating table."

A faulty firing mechanism had prevented the IRA from inflicting on the Northern security forces, their heaviest casualties yet, in their ten year long campaign. If the Newry mortaring had succeeded, it would have put the Warren point massacre of August 1979, in which 18 British soldiers were killed, into the shadows. It would also have transformed 1980 security statistics, into a grim catalogue of death and sent flurries of foreign journalists over to Ireland, for yet another series of lengthy analyses, of Europe's longest surviving guerrilla army.

II The IRA Reorganised

II The IRA Reorganised

That the Provisionals have survived to remain that sort of threat, not only to the British Army and RUC, but to any hope that the British government has of creating a peaceful internal settlement, is due in the main to a massive re-organisation of the Republican movement, which was carried out from 1977 onwards.

Without that re-organisation, the IRA, would in all probability now, be a spent force and its leaders in jail or back home at their fireplaces, dreaming of what had been or what might have been.

Two factors led to the re-organisation of the IRA. The most important was the success of the RUC arresting and extracting confessions, from IRA volunteers and leaders. Between 1976 and 1977, when the interrogators of Castlereagh and elsewhere were working overtime, over 2,500 people, mostly Provisionals, were convicted of murder, attempted murder, and arms and explosives offences. Such was the success of the 'criminalisation policy', as it was called, that the then Secretary of State, Roy Mason, and his security chiefs at one time, thought they had actually pulled it off and defeated the IRA. "We were almost defeated," admits one present Provo leader.

The second important factor was the effect of the post Feakle ceasefire and peace talks of 1975/76, on the thinking of leading Provisional strategists. That ceasefire brought certain short term gains for the IRA. Incident centres to monitor British Army infringements of the cease fire, were set up and talks were held between Provisional leaders and British civil servants, at which the carrot of British withdrawal, was dangled tantalisingly over Provo noses.

But the ceasefire also created major long term problems for the Provos. It provoked a bloody Loyalist backlash, which tied up IRA resource and questioned long-held Republican assumptions, about the Loyalist community. It also gained the British Army and RUC time to recover from the trauma of 1974 and to collect vital intelligence, on an increasingly open and careless IRA. In addition, it allowed the British to formulate a radical change in security policy, of which the present H Blocks and Castlereagh were part.

With hindsight, the IRA was the net loser from the 1975/76 ceasefire and the subject itself remains a major and bitter bone of contention within the movement. "Disastrous", is how one member of the current Provisional IRA Army Council member describes it; 'a running sore", according to another IRA leader.

The ceasefire forced on the Provisionals a major political, military and strategic re-think of which the 1977 military re-organisation was an integral part. It also paved the way for a change in the leadership of the IRA; the present seven man Army Council, is dominated by Northern 'hawks' and radicals, who vow never to speak to the British again except from a position, of absolute strength. The result of the re-think was two fundamental changes in policy. The first was the concept of 'the long way', which was first outlined by Jimmy Drumm, ironically one of those intimately involved in the secret ceasefire talks, with the British government. That concept was articulated by him at Bodenstown in June 1977, as was the second major change.

That change was a political one and involved pushing the IRA and its political wing, Sinn Fein, in a radical direction and to involvement in trade union, poverty, housing and unemployment issues; what Sinn Fein President, Ruairi 0 Bradaigh, now calls, "occupying ground vacated by the Sticks (Official Sinn Fein)". That particular move has been far from as successful or complete as its architects planned and has caused the greatest tensions within the Republican movement since the Official/Provisional split of 1970. The fact that it has been at all successful rests entirely on the fact that those responsible for the military rebirth of the IRA, were also those backing the advocates of radicalism. In Republican politics the sword has always been mightier than the pen and this time in the IRA's history both sword and pen, were pointing in the same direction.

That change was a political one and involved pushing the IRA and its political wing, Sinn Fein, in a radical direction and to involvement in trade union, poverty, housing and unemployment issues; what Sinn Fein President, Ruairi 0 Bradaigh, now calls, "occupying ground vacated by the Sticks (Official Sinn Fein)". That particular move has been far from as successful or complete as its architects planned and has caused the greatest tensions within the Republican movement since the Official/Provisional split of 1970. The fact that it has been at all successful rests entirely on the fact that those responsible for the military rebirth of the IRA, were also those backing the advocates of radicalism. In Republican politics the sword has always been mightier than the pen and this time in the IRA's history both sword and pen, were pointing in the same direction.

The IRA of the 1980's which resulted from the re-think was no longer the victorious, 'people's army', of the early '70's, which would push the British into Belfast Lough, but a small, highly organised band of politically dedicated terrorists and guerrillas prepared to fight for years. One current Army Council member summed up the new strategy in the following way: "The IRA has the ability to force the British out, but by that, I don't mean militarily. But we can make Ireland so unpopular an issue; they will be forced to leave. Even at the lowest level the IRA has the capability to be a major destabilising force and we're prepared for the long haul; 30, 40 or even 50 years if necessary'.

In late 1976 the IRA's General Headquarters Staff established a 'think-tank', which was to examine ways of implementing this new thinking and to report back directly to the Provisional's Army Council. The 'think-tank' itself, was dominated by two Northern radicals, both former Brigade commanders recently released from jail. In early 1977, it reported back to the Army Council and recommended that the IRA should be split into two. One part was to be responsible for fighting the war. It was to consist in the main of new 4 or 5 man 'cells', or active service units, and the old British Army-style organisation of companies, Battalions and Brigades, were to be largely scrapped. The cells were to be responsible in the first instance to local Commands or Brigades, but ultimately, to a new 'Northern Command', which would replace GHQ as the main IRA coordinating body.

The other IRA, the 'open' IRA, was to fight the political war. They were mainly IRA men and women well known to the authorities, who would pass in to a new, 'Civil and Military Administration'. They would be responsible for, 'policing' the Republican communities and for pushing Sinn Fein in a radical direction. To the acute embarrassment of the Provisionals, that GHQ 'think-tank' report was captured by the Dublin Special Branch in December 1977, when it re-arrested the then Chief of Staff, Seamus Twomey. That day was an especially good one for the Special Branch. They also arrested Seamus McCollum, the man at the centre of an ambitious scheme to smuggle in an arm's consignment, from the Middle East. Earlier that month Belgian customs officials had discovered nearly 6 tons of Russian and French-made automatic rifles and machine pistols as well as; Bren guns, explosives, mortars, rockets, rocket launchers and ammunition, hidden in electrical transformers on board the MV 'Towerstream', which had just docked from Cyprus.

The 'transformers' were addressed to a 'front company' in Dublin, established months earlier by McCollum. The trace back to McCollum's Dun Laoghaire flat and Special Branch surveillance, netted an added bonus in the form of Twomey, who had brazenly eluded capture since his dramatic helicopter escape from Mountjoy in 1973. Although the re-organisation has undoubtedly revitalised the Provos, the most significant aspect of that development is that, it demonstrated for the first time since the start of the IRA's bloody campaign that the initiative in security matters, was now with the British.

In 1970, 1971 and 1973, the Provisionals had toyed with the concept of cells, or active service units; in 1973 they actually formed a number of such units with 40 men in Andersonstown in West Belfast. But those changes, if they had come about, would have been voluntary. The latest re-organisation was a matter of survival to them. The re-organisation has also made the IRA a more 'efficient' killing organisation, but it has necessitated a drastic reduction in the numbers, of active service volunteers in their ranks. A joint RUC/British Army assessment last winter, put the IRA's strength throughout the North at around the 300 mark, with perhaps as many as 3 ,000 active sympathisers providing safe houses, refuges, transport, etc.

To put that into proper context, the strength of the first Battalion of the Belfast Brigade in 1972 was 300, with the same in reserve; the total strength of the IRA in that year was between 1,500 and 2,000. Instead of growing as the guerrilla armies have to if ultimate victory is to be realised, the Provisionals are actually declining in strength.

To put that into proper context, the strength of the first Battalion of the Belfast Brigade in 1972 was 300, with the same in reserve; the total strength of the IRA in that year was between 1,500 and 2,000. Instead of growing as the guerrilla armies have to if ultimate victory is to be realised, the Provisionals are actually declining in strength.

Another principal, if rarely admitted reason for switching to a long war of attrition strategy, is that support for widescale IRA activity, has declined significantly in recent years. The war-weariness and pessimism evident in the Nationalist areas of the North, is also reflected in the attitudes of many in the movement itself, who see little to be gained by continuing the fight. But that sort of thinking is less true of the new IRA. They are the younger, more radical types who have seen little of life other than violence, dawn raids, interrogations, rioting, shooting and bombing. They have taken over the mantle of militant Republicanism from the men of the 'forties', 'fifties' and 'sixties' and are increasingly impatient with what many of them see as conservative political and military elements, in the old Dublin leadership. And the IRA they have created, is much more ruthless and doesn't need mass popular support.

III The War of Attrition

With the depressing prospect of a 'long war' in front of them, what then keeps the IRA going? Prime among the motives for continuing the campaign, is the hope that in the harsh economic climate of the 1980s, the cost of the North to the British will get so high, that they will be forced into looking for a way out. There's no doubt that the cost of shoring up a degenerating economy in the North, combined with the damage caused by the Provisional's campaign and the cost of the security and prison services has become increasingly burdensome for the British. Last year's subvention to the North from Westminster, which is the money the British have to find to make up the difference between income from taxes and public spending in the North, was equivalent to the five year refund demanded from the EEC budget by Margaret Thatcher.

The true cost of the Provisional's campaign can never be established, but the available figures show a depressingly upward trend for the British. Another factor prominent in IRA thinking is the belief that the longer the war goes on, the more of an embarrassment Northern Ireland will become internationally. This is especially so in the United States but also in Europe, where left wing leaders of the IRA believe it will cause increased pressure on the British, to arrange a long term solution, capable of providing stability and security, for profitable foreign investments in Ireland.

IRA leaders also believe that the longer the war continues, the greater the chances of another Loyalist reaction.

IRA leaders also believe that the longer the war continues, the greater the chances of another Loyalist reaction.

Although the IRA could start a terrible and bloody civil war in the North with a dozen or so well placed bombs, it hasn't done so and will not do so. It would certainly be the loser anyway. But the IRA has applied steady pressure on the Loyalist community mainly through the shooting of part-time and ex-UDR soldiers. In this respect, the possible reaction of Loyalist leaders like Ian Paisley, is particularly important. One independent observer and confidant of IRA leaders put it this way: 'They hope that by shooting Protestants in the security forces, they'll cause Ian Paisley to have another brainstorm and start another Loyalist strike. The hope then is that Thatcher, The Iron Lady, wouldn't do a Harold Wilson, but give the Loyalists an ultimatum. In which case it's all up for grabs!' Paisley, by that reckoning, is one enemy the Provos would prefer to keep alive.

The vehicle for these tactics is the new re-organised IRA. The process of re-organisation started, by some accounts, in the Spring of 1977 and according to one leading IRA source, is still going on. Belfast, where the successes of the RUC were most evident, was the first to be re-organised, largely under the direction of a former Belfast Commander and a former Brigade Adjutant. Most of the old companies were gradually dissolved and their least known members re-trained and passed into the new four man cells. They were joined by new recruits. The old Battalion staffs were also dissolved and the Belfast Brigade assigned the task of coordinating the new cells. The Belfast Brigade still has three Battalions but they are composed of known IRA men who passed into the new civil and military Administration wing of the movement.

The other seven areas of IRA activity in the North, Fermanagh, East Tyrone, South Derry, South Down, North Armagh, Derry City and lastly South Armagh, were with varying success re-organised during the latter part of 1977 and most of 1978. South Armagh, where the IRA had always operated what amounted to a form of cellular structure, was the last to be re-organised in the Spring of 1979. In fact little was changed in South Armagh, except the area's relationship to the new Northern Command. The captured British Army intelligence assessment of the IRA, which fell in to the hands of the IRA in January 1979 (it was studied for several months before release to the Press Association in May), demonstrated the dearth of information about the new structures in intelligence circles.

In 'a tentative order of battle', the document's author, General Jim Glover, supposed that all the new cells were directly coordinated by the Northern Command. In fact it seems that there are a number of structures interposed between the Northern Command and the cells. Some areas, like Belfast, are coordinated by a Brigade staff. Other areas are coordinated by local Commands, a watered down version of a Brigade Staff. Some areas are so weak that they can only support one or two cells and they are directly coordinated, by the Northern Command. One area still retains the Battalion structure, and the three Battalions in that area report to, and are coordinated directly by the Northern Command.

It's a confused and mixed structure whose features seem to be determined entirely by area strength. The effect though is to make Army and RUC penetration extremely difficult.

Its principal advantage seems to be increased security and secrecy for the cells, but its Achilles heel is that it is highly dependent on good coordination at local Brigade and Command level, as well as at Northern Command level, what the British Army terms 'middle management'. The arrest and imprisonment of a small number of leaders would seriously impair the organisation - hence demands from senior British Army officers after Warrenpoint for the introduction of selective internment.

Although British Army sources claim that the IRA structure has now been penetrated in Belfast and East Tyrone, the successes the security forces have had this year, seem to be the result more of increased undercover surveillance and disruption of IRA communication and co-ordination, than from information supplied by informers. Indeed one security force source complains that they haven't received one decent bit of inside information from the Northern IRA for more than a year.

A vital element in the new structures is recruitment. The old days when virtually anyone could join the IRA are seemingly over. One IRA leader says that vetting of potential recruits is now so thorough, that only two out of every 13 applicants are accepted and sent on for training and thence into the cells. The IRA also says that the average age of new recruits is 18 or 19, an assertion that would seem to back IRA claims that the organisation has passed through the generation gap problem that always has spelled defeat for past campaigns. However, it's clear from a number of recent arrests, such as that of an M60 ambush team in Belfast this year, that the IRA is still heavily dependant on what General Glover called, 'the intelligent, astute and experienced terrorist' .

The IRA also claims that less than 50 per cent of new recruits join up for the personal motive of seeking revenge for British Army violence and that most are politically committed to, 'a socialist republic'. Not even the IRA can know that for sure, but if it is true, then the policy of 'Ulsterisation', involving gradual withdrawal of troops from Catholic areas, will have less of an effect on the Provos, than the architects of that policy hoped.

Once a recruit is accepted by the IRA, he or she is taken along with three or four other recruits for training across the Border in the specialism, e.g. assassination, sniping, bombing, etc. that that cell will later employ. In contrast to the past when whole companies could be trained without firing a shot, all recruits are now trained using live ammunition. This has enabled IRA men to 'sight' sniping weapons more accurately, it is claimed, and this sort of practice accounts for the success of the M60 machine gun in Belfast ambushes. When the M60 appeared on the scene in 1978, it was considered a propaganda weapon and too cumbersome and inaccurate for urban use; in fact the M60 has been responsible for 8 security forces' deaths since then.Recruits are also given anti-interrogation training on a scientific basis. Simulation is never employed, but IRA leaders have isolated a dozen CID interrogation techniques, which they instill into their recruits. Cell members are also encouraged to adopt false identities and discouraged from habituating known Republican haunts.

IV Bankrolling the IRA

The British Army reckons that the Provisional IRA campaign and related political activity, now costs the organisation some £2 million a year. In 1978, General Glover estimated that it cost £780,000 and that income exceeded that amount by £170,000, which was all spent on arms and explosives. It's impossible to verify the Army's claim that inflation has more than doubled the Provo's costs since 1978; one source says that, one spin-off benefit from the slimmed down re-organisation was a saving of money, However, there are one or two errors in Glover's calculations which as a result, seriously understate the amount the IRA has left for arms spending.

The first relates to income from theft. Since 1977, nearly £5 million has been stolen in the South and nearly £1.5 million in the North. According to reliable sources, at least a third of the money goes in to Provisional coffers; the rest to the INLA, freelance Provos and criminals. That would make the Provo's income on average during that period, over £650,000 per annum. The second mistake, relates to expenditure on newspapers and propaganda. According to a reliable Source, the Provo's newspaper, An Phoblacht/Republican News, which sells 34,000 copies each week and employs 12 full time staff, actually makes a profit. So the Provo's surplus for arms purchases, could be as much as £300,000 more than Glover estimated.

This would accord with some quantifiable facts about arms shipments. The Towerstream consignment, by General Glover's own reckoning, would have cost about £400,000, notwithstanding the cost of arranging it. The M60's, which came along with some 40 military Armalites stolen from the Danvers US armoury in Massachusetts in 1976, would have cost about £50,000. That's over £450,000 on arms spending in one year.

Other items in Glover's account like money spent on pay are confirmed by IRA sources, but others are impossible to check. The amount of money gained from 'racketeering' for instance, is an example. There's no doubt that numerous businesses, pubs, clubs, taxis, etc., in Republican districts, do pay to the IRA. The money is collected by the Civil and Military Administration and can vary from £15,000 to £20,000 per annum, from a large club to £2 per week, form a comer shop. No one will say whether its 'protection' money or 'voluntary donations'.

An incidental factor resulting from re-organisation is that now, less money strays into private pockets, or so it is claimed. In the past it was not unknown, and there are IRA men in jail to prove it, for O/C's and Adjutants in some areas of Belfast, to send their men out unknowing, on 'unauthorised' robberies for their own enrichment. Equally, it was not unknown for those volunteers themselves to take a cut.

V Foreign Adventures

Until 1978, the Provisional IRA had operated exclusively in Ireland and in Britain. But in that year there were bomb attacks at BAOR bases in Germany, followed by more bombs the next year. In early 1979 the British ambassador to the Hague, Sir Richard Sykes, was shot dead and a Belgian bank official was also killed in mistake for the British ambassador to NATO.

Until 1978, the Provisional IRA had operated exclusively in Ireland and in Britain. But in that year there were bomb attacks at BAOR bases in Germany, followed by more bombs the next year. In early 1979 the British ambassador to the Hague, Sir Richard Sykes, was shot dead and a Belgian bank official was also killed in mistake for the British ambassador to NATO.

This year, three British soldiers in Germany have been shot, one, a colonel, was killed by the same 9mm pistol used to kill Sykes. The bombings and shootings were the work of two separate IRA cells, who had travelled to the Continent in the guise of Irish building workers. Both have since returned to Ireland. Contrary to press speculation, the killings and bombings were not aided by the Baader-Leonhof gang, or other anarchist groupings, but a short term, and largely unsuccessful attempt, to arouse western European interest in the war in Ireland.

According to one British Army source, 'there are no operational links between the IRA and any of these groups'. By 'these groups', he meant not only the Baader-Meinhof group, but also ETA, the Bretons and the Corsicans. The guns that come from those sources are few and far between. The IRA buys its weaponry in Europe and the Middle East from conventional black market sources, who also supply training.

The last two years have seen though, the severing of an important link with the PLO; the British Army says that, the Towerstream cargo, at least in part, came via the PLO. Now Yasser Arafat says the link has been formally ended, in return for Dublin and EEC recognition of his cause. Some mystery however, surrounds the link with Libya's Colonel Gaddafi, which most people thought had ended with the deportation of the last remaining Provo contact man, in early 1975. Now there is speculation that the link might have been re-established.

When the IRA's Director of Operations, Brian Keenan, was arrested in March last year and sent to Britain for trial on offences related to the 1974/75 bombing campaign there, he had on him a torn half of a Libyan dinar bill; a recognition signal that was used a lot during the 1972/75 liaison between Gaddafi and the IRA. Another curious piece of Libyan jigsaw has also recently come to light. In August last year, a shady arms dealer, called Sadiq Baahri who operated his arms business from a legitimate export agency in Athens, disappeared while flying in his private jet, on a flight from Cairo to Jeddah, in Saudi Arabia. Reliable Arab sources in London now say that Baahri had incurred Gaddafi's displeasure, for refusing to arrange an IRA arms shipment. The rumour in Libya, say the sources, is that Libyan jet fighters forced his plane down at Benghazi, where he now languishes in jail.

VI Tactics

In its campaign between 1977 and 1980, the Provisional IRA has demonstrated what for the RUC and British Army, must be an irritating ability to switch tactics. Along the targets chosen for one to nine month campaigns have been businessmen, off duty UDR men, a sustained attack on the British Army and prison warders and the killing of prominent people like Lord Mountbatten. Bombing targets have switched from coordinated, six county wide attacks and smaller scale attacks on commercial premises, government buildings, hotels, banks and factories, to the blasting of town and village centres.

Methods of attack have also varied. Blast incendiaries were introduced in 1977, until the holocaust of La Mon, when they were temporarily dropped. Car bombs have made a recent come back, but so far only in rural towns. Intruder detonated bombs and long delay fused bombs, were introduced during that period. But while these and other more well known devices like culvert bombs and land mines, accounted for heavy security forces' casualties, it was the introduction of the radio detonated bomb in 1978, but especially in 1979, that really re-imposed the IRA's threat.

In 1978, radio bombs were tried out in various areas of the North, but only one member of the security forces was killed by one. In 1979, however, radio bombs accounted for no less than 29 of the 86 deaths, meted out by the IRA, and this year they have killed 6 out of 30. The radio bomb was also used in two of the IRA's most traumatic deeds of the last 10 years; the killing of 18 soldiers at Warrenpoint and the assassination of Lord Mountbatten and his boating party, in August 1979.

In 1978, radio bombs were tried out in various areas of the North, but only one member of the security forces was killed by one. In 1979, however, radio bombs accounted for no less than 29 of the 86 deaths, meted out by the IRA, and this year they have killed 6 out of 30. The radio bomb was also used in two of the IRA's most traumatic deeds of the last 10 years; the killing of 18 soldiers at Warrenpoint and the assassination of Lord Mountbatten and his boating party, in August 1979.

The development of the radio bomb, like the unsuccessful attempt to mortar Newry RUC station, also demonstrate another worrying factor for the RUC and the British Army. That is, the IRA's technical ingenuity.

That has been amply demonstrated by the IRA's use of huge quantities of explosives, not only in radio bombs, but also in car bombs and landmines since 1978. Bombs of 1000 or 2000 Ibs are now quite common. In 1977 and 1978 the IRA was forced to experiment with new ways of producing explosives. Legislation in the South had outlawed the sale of fertiliser containing benzine, which together with sugar, went to produce the terrifying blockbuster car bombs of the early 1970's; and they virtually disappeared as a result. In late 1978, however, the IRA devised a new method of producing home made explosives. The IRA discovered that if ordinary fertiliser was 'cooked' in water, the resulting crystals produced after the 'dirty' water had been skimmed off, made high quality explosive, when mixed with metal fillings, usually aluminium, and diesel or carbon.

The explosive produced is detonated by a pound or two of commercial explosives and can, as the radio bombs have proved, be enormously destructive. Its drawback is that it stinks to high heaven and is very unstable. As a result, it is usually only 'made to order', in two stills the British Army thinks the IRA has deep across the Border.

While the IRA has, thanks to that sort of ingenuity and the re-organisation, made a considerable comeback since 1977, the organisation and its campaign of death and destruction has at the same time, been limited effectively to three of its eight operational areas.

Those three areas are of course; Belfast, South Armagh and East Tyrone. Even so the level of activity in those areas has also declined.

In Belfast for instance there were 109 bombing attacks and 51 ambushes and gun attacks on the RUC, British Army or other security force personnel during 1977. In 1978, that had declined to 101 bombings and 29 shootings and in 1979, to only 39 bombing attacks and 20 gun attacks. This year seems to be keeping in line with that, at 13 bombings and II gun attacks.

In East Tyrone it has been much the same story. 22 bombing attacks in 1977 and 9 gun attacks; in 1978 there was a rise to 36 bombings and a fall to 7 gun attacks and in 1979, there was a drop to 18 bombings, but a rise to 13 shootings, aimed at the security forces. South Armagh IRA units on the other hand display all the characteristics of classic guerrilla fighters. Very few incidents occur in South Armagh, compared to areas like Belfast. But those that are carried out, have been devastatingly effective. In 1977 there were only 5 bombings and 7 shootings directed at the security forces; a low level of activity that was caused by increased SAS activity in the area.

In 1978, there was a rise to 15 bombings and 5 shootings and again the same the following year. This year, so far, is following that pattern, 6 bombings and 3 ambushes.

Between 1977 and 1980 so far, the IRA in those three areas, killed 173 people of the 230 total, killed by the IRA in the North. That included businessmen, civilians, British soldiers, RUC men, UDR men, ex-UDR men and prison warders. Belfast IRA cells incidentally, were responsible for the highest number of businessmen killed, 6 out of 7; the highest number of civilians killed, 30 out of 49 and the most prisoner warders, 11 out of 15. South Armagh clearly concentrates on the British Army; its IRA units killed 36 of the 68 soldiers killed by the IRA during those years.

The other five areas of IRA activity, are quiescent by comparison. Derry and South Derry are virtually at peace and South Down, Fermanagh and North Armagh very quiet.

However, the statistics do not tell all the story. There have been more security force deaths and less civilian deaths from IRA activity, than for a long time. Furthermore, as the criminal damage payments bear testimony, the reduced level of bombings has not reduced the damage caused.

As well the contrasting numbers of deaths of Provisionals compared to those in the security forces, show the IRA is losing less men for every death they inflict on the security forces, than ever before in this campaign. In terms of security forces' kills against the IRA, the picture is even bleaker for the British. In 1979 and 1980 premature explosions, not Army or RUC bullets, killed 4 of the 6 dead IRA men. All the figures available point to more effective activity by the IRA.

While 1978 and 1979 were 'good' years for the IRA, 1980 so far has been a bad one. Increased undercover operations have hampered organisations: IRA leaders admit that 5 out of 6 operations are now aborted thanks to surveillance. In addition frequent arrests and 7 day detention orders of 'middle management' leaders, have disrupted co-ordination and communication. (One Northern IRA activist was told by the British Army officer who arrested him, that orders were just that, 'disrupt them!'.) The IRA as a result, has spent most of this year killing 'soft' targets like off-duty UDR men and the campaign against prison warders has been halted to await the outcome, of the H Block negotiations.

But it is Charlie Haughey's tough police and legal moves against IRA operations in the Border counties, which has done more to impair the IRA in the last year, than the RUC and British Army combined in the last three. Cross border co-operation between the Garda and the RUC at Regional Commander and ground level, combined with meticulous Task Force searches of Border farms, have seriously disrupted IRA logistics and produced a number of significant arms and explosives dumps. Those tactics are described by one IRA leader as 'devastating' and things could get worse for the Provos if Haughey's attempt to activate the dormant, Criminal Law Jurisdiction Bill, for cross-border offences succeeds.

At the same time there are indications that the IRA could be conserving its resources for the 'long war'; to hit when and where it hurts. 'We could bomb all 'round us for three months and cause millions of commercial damage, but we'd lose 40 or 50 men and maybe kill 9 or 10 civilians in the process. What would be the point of that?', asks one Northern IRA leader.

Despite temporary or long term setbacks, the IRA remains essentially a product of an abnormal society in the North, what Tim Pat Coogan calls a 'faecal society'. The IRA is not the problem in the North, it is only a reflection of the problem. And as long as the problem remains unsolved, the IRA and its bloody campaign will persist. In that context, it's worth quoting General Glover's conclusion to his 1978 assessment of the IRA: 'The Provisional's campaign of violence is likely to continue, while the British remain in Northern Ireland'.

VII The Move to the Left

'The most successful radicalisation of the Republican movement since the Republican Congress, and it didn't cause a split'. That's how Sinn Fein Vice President, Gerry Adams, the man most identified with that radicalisation, now describes the recent political changes in Sinn Fein. The move to the left hasn't, it's true, caused a split in the Provisionals, but it has come very close to it. There is undoubtedly a division within the Provo ranks. The organisation can be said now to be roughly divided between North and South, old and young, traditional and revolutionary, but essentially between right and left.

The impetus for the move leftwards has come from a small group of Northern and especially Belfast radicals, whose influence far outweighs their strength. One Belfast leftist puts their numbers at no more than 30 or 40, but it is almost entirely because the present 7 man IRA army Council is like-minded, and are the men responsible for the military re-vitalisation of the IRA, that the leftists have exerted as much influence.Realistically, the Provisionals have yet to move much further to the left before the radicals can say that they have successfully, turned it into a socialist organisation.

More so than most political organisations, the Provisionals consist of a delicate balance of differing interest groups. Move them one way and the balance is upset. Most political organisations can withstand those sort of stresses and strains, but less so an organisation that is also fighting a, 'war of national liberation'. The leftists have been able to tip the balance so far and only a little at a time.

The bulk of Provisional supporters, especially in the rural, border areas, are traditional Republicans. Small farmers or country town merchants; what one Belfast radical calls, 'Fianna Failers with guns'. Their support, which is reflected in the vote for the 30 or so Sinn Fein councillors, is vital for the war effort. They provide the training camps, the dumps and safe houses. Many of them stayed with the Provisionals precisely because they thought the Officials were too leftist or Marxist. Much the same can be said for the older veterans of the movement; the men of the 'forties', and 'fifties', many of whom sit on the IRA Executive, the body that acts as the repository of Republican faith and which in 'war time', appoints the Army Council.

One such man, a Northerner in fact, who has spent 13 years in prison or internment camps, summed it up like this: 'I don't like this word Socialism. I wish they could find another word for it'. Others like Billy McKee, a former Chief of Staff and Belfast Brigade Commander, have dropped out altogether. When he last came to Belfast in May 1979 to speak to a welcome home rally for released blanket-man Ciaran Nugent, he was reportedly horrified at the number of foreign left wing posters and pamphlets, in the offices of Republican News, the voice of the Northern left.

Another group .whose dollars at least are vital to the Provos, are the Irish-Americans and notably, Irish Northern Aid, headed by veteran Republican and devout Catholic, Michael Flannery. Even in the early days, the Irish-Americans were a standing joke with Belfast Provos. It was common then for visiting Republican speakers from Ireland, to be taken by Flannery, for a new outfit of sober suit, tie and shiny shoes, before being let loose on the Irish-American faithful. Speakers were instructed by Flannery, never to refer to socialism and one such tourist can recall discovering unopened bundles of Republican News, lying dumped in dustbins outside Nor-Aid's Bronx headquarters. The Northerners were always too radical for the Irish-Americans.

Those are the traditional, conservatives forces within the Provos, ranged against the Northern radicals. Although there have been symbolic victories for them, notably the fusion, or takeover as some see it, of Republican News, with the Dublin based An Phoblacht, the real political debate has centred on the Provos 1972 policy document, 'Eire Nua!'

That document is identified in most people's minds with two traditional leaders, Sinn Fein President, Ruairi 0 Bradaigh and Vice President, Daithi 0 Conaill. At Sinn Fein's last Ard Fheis held in January 1980, but actually 1979's Ard Fheis, that document was changed for the first time since the new policy document which was adopted, 'Eire Nua - the social, economic and political dimension', was more a change in emphasis, than substance. The language was more socialist than the 1972 document, but some controversial clauses especially relating to the right to land ownership, merely changed or deleted by Sinn Fein's ruling body, the Ard Comhairle.

But what that document did do, was to set in motion a series of moves, which the radicals hope will turn the Provisionals leftwards. A women's committee was set up to devise a policy document to be debated, at the next Ard Fheis. The policy, which it has devised, reflects the difficulties the radicals are having converting their more conservative and Catholic sisters. Women, who have had abortions, are not condemned but the system that forced them to is. Moral issues like contraception and divorce should, the committee decided, be left to individuals.

Similarly, an Economic Resistance campaign was re-emphasised in the new document and a committee headed by Post Office Engineering trade unionist, Paddy Bolger, also set up to devise a policy for the next Ard Fheis.The economic resistance campaign foresees the involvement of Sinn Fein in trade union struggles like the P A YE marches and opposition to the National Wage Agreement and to push Republican issues at grass roots union level. It also intends to encourage housing, unemployment and social agitation by the Republican movement. Those two developments reflect a political change in Republican thinking that is part and parcel of the IRA's long war scenario. If the IRA must stay around to fight that war, say the radicals, then Sinn Fein must have something other than the initially intoxicating, but in the long term irrelevant, slogan of 'Brits Out!'

But those two developments and in particular, the Economic Resistance campaign, are at the root of conservative unease with the move leftwards. Not only is Economic Resistance uncomfortably reminiscent of the 'communist' Officials and their concept of a National Liberation Front. It also smacks of the same politics that led to the 1970 split over recognition of the two States in Ireland. For an Economic Resistance campaign to be really successful, it clearly needs to get into the businesses of making demands on the State, both North and South of the Border. Building campaigns around the demand for jobs or better housing will lead; say the traditionalists, to a de facto recognition, of Leinster House and whatever Humphrey Atkins can devise in the North to replace Stormont. So far an uneasy compromise has been reached, which allows for agitation in the South but only glorified social work in the North.

The most significant change in Eire Nua has come in the present differing attitudes of the IRA Army Council and Sinn Fein, to the core of the 1972 document. That is Federalism, or the creation of strong Provisional government in Ireland, when the British withdraw. Underlying Federalism was an implicit hope that it would mollify Northern Protestants and persuade them that, however unrealistic the chances of re-unification, the Provisionals didn't really bear Protestants there any ill will. The Provos were even prepared to give them a large measure of self-government, should the distant dream of re-unification be realised.

The Provisional most closely identified with Federalism, is of course, Daithi 0 Conaill. As Director of Publicity of the IRA between 1972 and 1975, O'Conaill spoke more often of the need to build a 'United Ulster', than a 'United Ireland'. He even banned the latter phrase from Provisional vocabulary for a while. In 1974 he praised the UWC Loyalist strikers; they showed 'tremendous power and acted in a responsible way', he said. On several occasions since, he has described moves by Loyalist paramilitary groups towards the idea of Northern independence, as 'encouraging'.

Although Federalism remains the official policy of Sinn Fein, it has now been rejected by the radical and Northern dominated IRA Army Council. One Army Council member explained why: 'We are opposed to it because of the historic abuse of power by the Loyalists in the North. Federalism wouldn't unite the Irish people, but perpetuate sectarian division'. O'Conaill's thinking as represented by his public statements between 72 and 75, led directly to the Feakle and post-Feakle talks, but is now light years away from the Northern radicals. Northern Provisionals are undeniably more sectarian than their Southern counterparts, not least of all because of the bloody carnage in Belfast and elsewhere in the North. Their view of Northern Protestants, influenced by left wing groups like the Peoples' Democracy, is that the Northern State is irreformable and so are most Northern Protestants.

The unease and leftward shift in Republicanism, allied to the change of attitude on Federalism, has led inevitably to talk of there being two identifiable wings in the movement. One led by the spokesman for the radicals, Gerry Adams, and the other led by 0 Conaill. Twice last year the tensions between the two surfaced briefly. The fist was in reaction to Gerry Adams' fiercely socialist oration at Bodenstown. The other was at a special weekend conference of 200 Sinn Fein leaders at Athlone last October:

By coincidence, the Dublin Sunday World, published that weekend, an essentially accurate report claiming that Federalism was about to be abandoned and the Provos were about 'to lurch to the left'. The article also talked about the 'waning influence', of O Bradaigh and O Conaill. The effect of the article when it landed on breakfast tables at the Hudson's Bay and Shamrock Lodge hotels where the Provo delegates were staying, was to say the least, traumatic. According to one source, the uproar from rural delegates was such that, Adams was forced to deny other reports, that there were Marxists in the Provos.

According to another source, 'there would have been a walkout if he hadn't. Needless to say leading Provisionals are not keen to talk about Athlone. 'We wouldn't want to air that sort of thing in the press', says 0 Conaill, 'we don't have any fundamental differences and any we do have, will be settled internally'. But according to another source, Athlone was something of a victory for the traditionalists - 'Marxism is now a dirty word in the Provos', he says.

Since then, the Provisionals have spent their time healing wounds. O Conaill was elected joint Vice President with Gerry Adams at the last Ard Fheis and Ruairi O Bradaigh, a consummate wound healer if ever there was one, symbolically spans the gap between.

And between May and July this year, leading Ard Comhairle members representing both wings, have toured the country. In a public show of unity, O Bradaigh, O Conaill, Joe Cahill, Charlie McGlade, and Niall Fagan of the traditionalists, and Gerry Adams, Foreign Affairs spokesman Richard Behal, and An Phoblacht/Republican News editor, Danny Morrison for the radicals, took pains to assure Sinn Feiners throughout Ireland, that the trouble was over and that unity and peace reigned once again in their movement.