Anger and indignation in Ireland, Greece and Tunisia

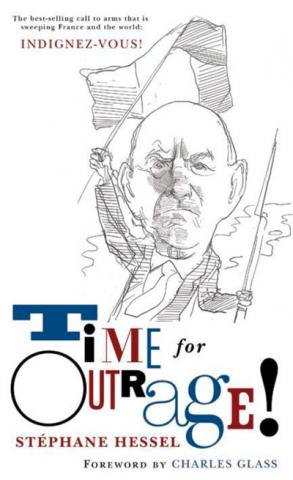

When Stephane Hessel wrote in Time for Outrage! - published earlier this year - that indignation with injustice should turn to ‘a peaceful insurrection’ perhaps he did not expect that the movement of ‘indignados’ in Spain and ‘aganaktismenoi’ (outraged) in Greece would take his advice to heart so soon and so spectacularly. Last Friday, The Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities hosted a discussion on the peaceful insurrections taking place across Europe titled 'The rise of the indignant: Spain, Greece, Europe' and featuring contributions from, amongst others, Costas Lapavitsas, Costas Douzinas and Illan Rua Wall. You can listen to and download the full discussion here, and a transcript of Illan's contribution is below.

Politics is back on the streets of Europe, that much is clear. The PIGS are striking back. Portugal, Ireland Greece and Spain. Except that’s not quite right. Today I would like to address the failure of Irish radicalism and contrast that with Greece and Tunisia, in order to begin to pull out a number of important lessons from the current wave of indignation and fury. I will suggest that when the media focus on anger and indignation they miss some of the most significant factors involved. I want to suggest that anger is only the beginning.

For the last twenty years, in Ireland, there has been a concerted effort to render politics as that which happens after and in the wake of the economy. Ireland fitted itself into a neoliberal globe as the subjugated outpost of post-politics: the Irish economic miracle or the Celtic tiger were placed at the heart of the political sphere. The neoliberal hegemony and its attendant withdrawal of the political was interiorised by vast swathes of the populace. And so, when it all fell apart, when the government nationalised the banks debts and declared lemon socialism, there was anger. Suddenly, everyone saw the bankers and the members of government as the ones who created and lived off a bubble rather than creating, as they projected, a stable financial system. The certainty that the people had felt from the providence and force of the market gave way to a screaming fury. Ireland was enraged and indignant. But nothing happened. There was no taking of streets, running battles with the police or fierce debates in the media. There was a collective gasp. All that was solid melted into air and Ireland was at last compelled to face with sober senses its real conditions of life.

There are of course so many reasons that Ireland has not come out onto the streets, both political and cultural, but I want to suggest that the election played a crucial role in maintaining the status quo. We have to remember that a myth had grown up around Fianna Fáil, the party of government, basically, for the last 30 years. A myth that they were undefeatable - after all, despite constantly falling electoral support, they had not been out of government for more than three years since the seventies. They had wound their tentacles through the political being of the country. Thus, when the crisis came and everyone knew that the cabal of politicians, developers and bankers were to blame, no-one could bring themselves to say that Fianna Fáil would or even could be defeated. The fury of the catastrophe became focused on the ejection and elimination of Fianna Fáil. They were perceived for what they were - a cancerous growth on the Irish body politic. A huge effort went into their defeat in the February election. However, this is the problem. The election was seen as a cathartic moment. Everything led up to the defeat of Fianna Fáil. There was no politics that was not consumed by this. The indignation burned itself out in the ballot box. There was fury, but no radical subjectification through that affect. Instead it turned inwards; the question became: ‘How we can get back to where we were?’ rather than the radical refusal that we find elsewhere. There was a double think – ‘We know market-capitalism failed us, we know neoliberalism doesn’t work, but the world keeps turning and so what option do we have but to fit ourselves back in again to the structure?’ The subject, created by this discourse, is one who is pacified by her relation to the global market. The political remains withdrawn, and all that has changed is that the Irish are more precarious.

Quite plainly, the failure of Irish anger to mobilise the population is crucial. The reason that the country will accept round after round of recapitalisation is because there remains a hope for representational rather than direct politics. What we learn from Greece, Tunisia and Egypt is that everything changes when the space of politics shifts to the streets; from the stable and preconstituted zones of parliaments and negotiating rooms. So let me make three observations about the events in Greece and Tunisia by way of contrast; these could be summed up as organisation, alegality and refusal.

The first thing to note, in the comparison with Ireland, is organisation. The United Left Alliance and the Irish Communist Party variously try to organise in order to generate resistance. However, what has happened in Greece, Tunisia, Spain, Egypt and beyond is precisely the opposite. People come out and refuse the current state of the situation. Their anger brings them to the streets, and there they learn radical politics; they learn to ‘overthrow’. We see this in Greece (I rely here on a description in the latest edition of the Journal of Critical Globalisation by Sotirakopoulos). By 15 June Syntagma Square appeared to have divided in two - with the political ‘frustrated’ in the lower part of the square gathering around the Free Assembly while the upper half of the square around the parliament seemed full of the ‘apolitical’ frustrated. The radical left feared that the majority of the indignants were merely there for pleasure rather than some sort of serious political programme. However, when the police rounded on the occupiers on 15 June, the apparently ‘fluffy’ apolitical non-violent side of the square fought back with vigour. They had been subjectivised in their being-together against the state of the situation. They were not organised, they were not trained, not indoctrinated. There was no party revealing the reality behind the ideology. There certainly was critique, argument and solidarity. However, these were not mediated in the traditional sense by a party structure.

This subjectivisation is fascinating. In Tunisia and in Egypt, we find a crucial example of how this works. In both countries, there was a huge effort to disrupt the ordinary running of the state. Variously, the police were restrained and the civil service were blocked from undertaking the ordinary workings of the state bureaucracy. But of course, in Tahrir Square, life continued without the police and without the civil service. The pre-constituted order was suspended and instead spaces of alegality, or of life without state (in Agamben’s words) were generated. Rancière calls this ‘real’ democracy, ‘where liberty and equality would no longer be represented in the institutions of law and state, but embodied in the very forms of concrete life and sensible experience’ (Hatred of Democracy p3). Thus, in Tunisia we find the refusal of representation coupled with the opening of an interval between state and life. The ‘order’ of the state, in many instances, is suspended, and in that gap there is just life without law. This sense of the suspension of the state however, does not lead to rape, murder and civil war – as the Hobbesian myth of the state of nature suggests. In fact, it is precisely the attempt to once more create obedience to the social contract that has lead to the most violent confrontations. In Greece, it strikes me that a similar event has taken place. Over and again the people come to the squares and refuse. They refuse labour, they refuse representation, they refuse! In the space of this refusal an interstice opens, and in that space a different politics emerges.

The final point I want to make concerns that refusal. In Tunisia it begins with anger. The story of Mohammed Bouazizi has been told over and again. This is the man who set himself alight after an altercation with the police and a failure of response from the local government. Bouazizi’s situation resonated with the people. However, they were not just angry with bureaucracy or the police. On the streets they cried Dégage – clear out, get out. They manifested a simple refusal of the situation. It was not just Ben Ali they were refusing, but the entire situation. There is no attempt to reform, to work within the system. Rather, the people refuse representation. Like the characters in Jose Saramago’s novel Seeing, each provisional government since 14 January has been silenced by the simple refusal of representation. This refusal at once asserts the unacceptability of the secret police and Ben Ali’s neoliberal reforms, but it is more than this as well. It is a rejection of the current positioning of the Tunisian populace in relation to the globalised world order. This is the same relation that pacifies Ireland.

In conclusion, anger and indignation provide the starting point. At one stage in the early nineties, Jean-Luc Nancy demanded that:

‘Anger is the political sentiment par excellence. It brings out the qualities of the inadmissible, the intolerable. It is a refusal and a resistance that with one step goes beyond all that can be accomplished reasonably in order to open possible paths for a new negotiation of the reasonable but also paths of an uncompromising vigilance. Without anger, politics is accommodation and trade in influence; writing without anger traffics in the seductions of writing.’ (J-L, Nancy, ‘The Compearance’)

Anger is the political sentiment par excellence. Precisely because it draws us together on the streets. At that point the radical subjectivation begins again. We make friends, we learn together. This is what we were beginning to see in the student protests before Christmas; in the repetition of bodies on the street a radical sense of being-together began to emerge. This is precisely what the TUC strategy misses. Anger, expressed in one massive spectacle and subsequently mediated through representatives, is not enough. It is the continuing refusal of representation and the subjectivisation of the streets that has effect.

Illan Rua Wall is a Senior Lecturer in Law at Oxford Brookes University and a contributor to Critical Legal Thinking.

Syntagma Square image: mkhalili.

Tahrir Square: Jonathan Rashad.

Tunisia protest: gwenflickr.

{jathumbnailoff}