Our moral duty to lie to pollsters

Week three of the 2011 general election is now underway, and the agenda is still largely dominated by the state of Ireland's beleaguered economy. Econospeak has overtaken Irish as our second most popular language, and the front pages are still filled with stories of bailouts, banks, bondholders, budgets and Brussels. The other big issue of the election, political reform, occasionally gets a look in, but the broadsheets are dissecting daily the minutiae of our economic situation - and with good reason. Few forces are strong enough to shift the economy off the front page, writes Joe Galvin, and the most powerful of those is the opinion poll.

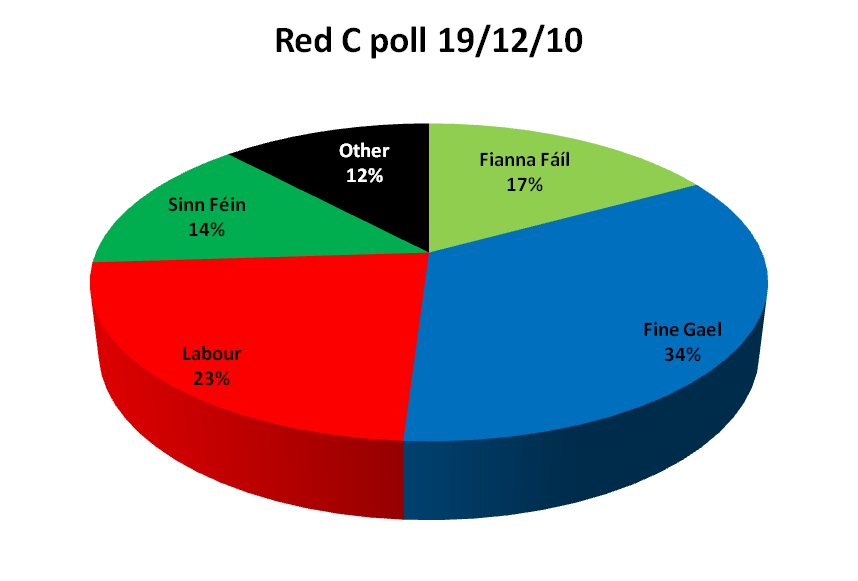

Another day, another poll. On the night of the 14 February, TV3 News reported the results of the latest Irish Independent/Millward Browne poll. The signals, we were told by Alan Cantwell, were clear: "Fine Gael is on course to forming a single party government," he said, and who should disagree? Fionnán Sheahan has voiced similar opinions in the Irish Independent, while Noel Whelan has conceded that the polls mean Fine Gael will take at least 70 seats. The polls, scientifically conducted and carefully prepared, all point in this direction, and the analysts are falling over themselves to outline exactly what that means. Single-party government, coalition, 15 seats for Fianna Fáil, or 25...the polls are pored over by the media in an effort to 'call' the election results ahead of time.

The polls are a media obsession, and it is easy to see why. They put numbers on the game, and they provide masses of straightforward copy. If you still have a copy when you read this, glance through the Irish Independent 15 February edition. The front page is filled almost entirely by the polls (with a little space on the broadsheet edition kept aside for a story about burning bank bondholders) and the coverage overall comprises nine stories (11 if you include the editorial page) and three full pages of copy. It is the same any time a newspaper or media network commissions a poll; it receives enormous coverage, and is analysed almost into oblivion. The argument for such blanket coverage is no doubt that it is in the public interest. These polls, we are told, help inform voters, and some scholars suggest that polls can provide citizens with cues to aid them in their political decisions.

But is that true? The overwhelming weight of academic literature suggests it is not. In a study conducted by Cheryl Boudreau and Mathew D. McCubbins of the University of California it was found that "polls do not necessarily help subjects to improve their decisions". Boudreau and McCubbins also found that "the direction of the majority (regardless of whether it is correct) exerts an enormous influence on subjects' decisions, while the size of the majority does not".

In other words, polls tend to reinforce majorities, no matter how small. This is worrying if true, but even if it is not we are left with the fact that polls are of negligible benefit to the electorate (an opinion supported by numerous scholars) despite the masses of coverage they receive. So if they are not for the electorate, then who are they for? There are only two other actors that can benefit; they are the media and the political parties themselves.

"Polls shift the agenda away from crucial issues of genuine import while providing little in the way of value in themselves"

Again, it is eminently clear why polls benefit the mainstream media. They provide easy copy and, certainly in terms of election polls, they dominate the broader media agenda and can generate sales or increased viewing figures for the commissioning news organisation. It is scarcely more complicated than that; an election-time opinion poll can comfortably fill three pages of a newspaper, and give what are now desperately overworked journalists a break from the daily drudge of churnalism. This is problem enough; polls shift the agenda away from crucial issues of genuine import while providing little in the way of value in themselves. This is, however, a relatively minor issue. The careful cultivation of the numbers by political parties is a far more malign influence, and far more nuanced.

Major parties have come to rely heavily upon focus groups and opinion polls to dictate their policy agenda, shape public opinion and cultivate their public image. In 1992, when Bill Clinton was attempting to achieve the Democratic presidential nomination, his star was almost eclipsed by his pollster Stan Greenberg. Greenberg drove Clinton's campaign through careful study and cultivation of the numbers. He was a central figure in Clinton's campaign success; he went on to massage the numbers for Tony Blair. Any wealthy catch-all party worth its salt has its own Stan Greenberg, and poll management has become almost as important as policies or campaigning.

How is it done? The most simple and perhaps most subtle method is by framing questions to direct pollees towards specific answers. We can take a simple and concrete example of this as it is a feature of almost every issue-based poll. On February 3, an Irish Independent/Millward Browne poll asked the question "Would you be in favour of a property tax to support public finances?" Unsurprisingly, 70 per cent answered no. As Gavan Titley rightly pointed out on Tonight with Vincent Browne on February 2, very few people are likely to agree to their money being taken away. No-one wants to pay for as abstract a concept as 'public finances'. This result, however, has to be taken with a pinch of salt. The context of the poll was significant, as it came soon after the reduced January paypackets, but perhaps more significantly, and certainly more significantly in any long-term analysis of polling, was the framing of the question. The question did not revolve around, as Titley pointed out, what kind of society people wanted to live in or whether people would be happy to pay more for improved hospital services. It focussed on the pollee getting less money to pay for something relatively abstract. This inevitably distorts the results, but it undoubtedly influences those who see those same results. The line becomes 'property tax is bad' without any in-depth analysis of the figures.

However, this kind of framing is of less significance when it comes to candidate and party polling. These polls are generally presented as a straight choice, and so may give the impression of higher accuracy. This is not necessarily the case. Polls can always be inaccurate; to give a straightforward example, polls for this election may have been influenced by the so-called Shy Tory factor, a phrase coined in the UK in 1992 after the Conservatives defied the poll predictions to win the general election. The logic was simple; pollees were unprepared to disclose their intention to vote for the Conservatives, and thus the polls heavily underestimated their position. In America, the influence of the Bradley effect, where undecided white voters tell pollsters of their support for non-white candidates, has long been discussed. Pollsters are almost entirely dependent on our honesty; a simple lie, told by many, can destroy their careful preparations. Thus, if this election was to experience a Shy Fianna Fáil factor – not beyond the realms of possibility – we may see those points 'stolen' by Labour and Fine Gael eaten away at come the count.

As well as this, we have to ask the question, as Arianna Huffington once did – who answers the phones? In any phone poll, approximately 20 per cent hang up immediately, and a further 20 per cent are unavailable. Huffington quipped that this means phone pollees comprise the lonely and unemployed; facetious, perhaps, but the question cannot be ignored. Can polls always guarantee a genuinely representative sample?

So the polls can be inaccurate, for a multitude of reasons, but this is not always the case. However, the inaccuracy is less malign than the influence polls have on party decisions. Polls decide what parties will say or, indeed, whether they will say anything at all. A perfect example is the reticence of Fine Gael to put Enda Kenny under the media spotlight. Poll leaders in any country, perhaps influenced by the majority effect highlighted by Boudreau and McCubbins, often step outside the limelight as leads have a tendency to self-perpetuate. Sometimes a point is reached where it is no longer necessary to campaign, and parties simply massage the numbers until they are home and dry. Tony Blair was guilty of this during his tenure as British Prime Minister. He rarely, if ever, engaged in election debates as he only had points to lose and little to gain.

"Policy is all 'poll-driven'... candidates must be ready at all times to assume the required shape and posture"

Kenny's decision to withdraw from the TV3 debate was arguably a response to the steady rise of Fine Gael in the polls. He has since returned to our television screens, but it is likely his handlers made the judgement call that it was too big of a risk to withdraw entirely; after all, Fine Gael's lead is not as decisive as Blair's, and the British electoral landscape is more predictable than Ireland's. Now Labour and Fianna Fáil, worried by the steady rise of Fine Gael in the polls, have finally set their stall out to attack Fine Gael's policies in a determined and substantive way, beginning with that €5bn 'hole' in Fine Gael's figures. It is all, to use that vile phrase, "poll-driven", as are most of the successful modern political campaigns. "Not only must the poll-driven campaign seek to shape and mould opinion," says Christopher Hitchens in his analysis of Clinton's 1992 campaign,"its candidate must be ready at all times to assume the required shape and posture."

The eventual result of this, in terms of national politics, is a slow development of consensus. Polling has a tendency to drive parties towards the centre, and this is plain to see in almost any established democracy. Ireland is no exception. Consensus on major issues tends to develop between political elites, and that consensus is often borne out of a careful reading of prevailing public opinion as opposed to any central ideological agreement. Differences between the parties most often arise regarding, for example, relatively minor budgetary or administration issues. Fundamentally opposing policies, if they do arise, are often proposed to appeal to a party's long-term base.

Ultimately, opinion polling is a process that is both demeaning and reductive to democratic politics. It is no coincidence that the word pollster was coined by Lindsay Rogers in 1949 to evoke the word 'huckster'. Rogers was worried about, as Christopher Hitchens put it, "the pollster's potential power to, in effect, wield the gavel at the town meeting - to frame a question in such a way as to limit, warp, or actually guarantee the answer". Rogers was not even the first to question the worth of polls; Herbert Blumer of the University of Chicago questioned "whether public opinion polling deals with public opinion" in 1948. So the dangers of poll dependence were noted very early, but quickly forgotten, and now opinion polling is an accepted and rarely questioned part of our political landscape. It seems Rogers's fears have come to pass. However, these modern day hucksters need one thing to fulfill their aims. They need us.

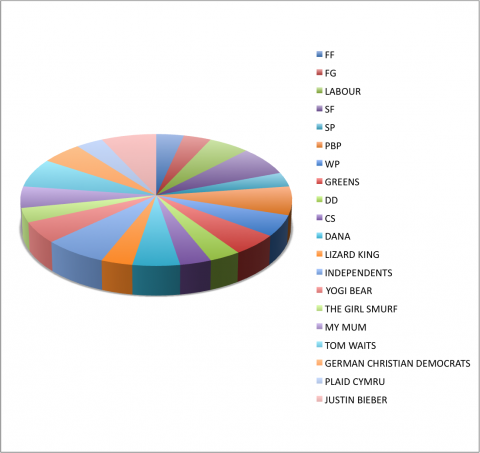

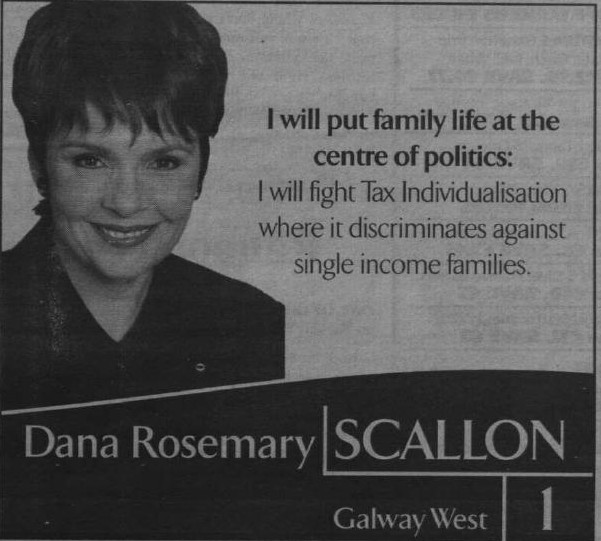

My advice? If you get a call from a opinion pollster, hang up the phone. Or, better still, spout the most ridiculous lies you can think of. When they ask you about the policies you are interested in, state that you are enormously troubled by the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Donegal South West. Profess your admiration for the political nous of Dana Rosemary Scallon. Outline your fear that Leo Varadkar is an alien lizard queen from beyond the moon. Obviously only the last is really believable, but anything that subverts the process is to be welcomed. Gum up that machine of political spin and public relations and that worthless process of polling. Give them nothing, or give them lies. It can be your own little act of revolution against consensus. {jathumbnailoff}

Top image by Bernie Goldbach, insideview.ie