The Extraordinary Life and Times of Sean McBride: Part 2

In the first part of his profile of Sean MacBride, Michael Farrell wrote about MacBride's involvement in the War of Independence and Civil War, his career as an IRA leader in the 1920s and 1930s and his role as a lawyer defending republican prisoners during the Second World War. In the concluding part of the article he looks at the formation of Clann na Poblachta and MacBride's role in the first InterParty government, including the Mother and Child controversy. He uses the recently released Cabinet papers to throw some new light on this period and then looks at the decline and fall of Clann na Poblachta and MacBride's emergence as a major figure in the international movements for human rights and disarmament.

Sean MacBride left the IRA in 1937 after 20 years of active involvement. He felt that de Valera's 1937 Constitution enabled republicans to achieve their objectives by peaceful means and he was opposed to the proposed IRA bombing campaign in England. He was quickly involved in an attempt to influence the social and economic policies of the Fianna Fail government. De Valera set up a Banking Commission in 1938 and MacBride worked with Bulmer Hobson, a former Northern lRB man, Luke Duffy, the secretary of the Labour Party, and a Mrs. Berthon Waters to draw up a minority report which was submitted under the name of one of the Commission members, Peadar J. O'LogWen. His fellow commissioners were astonished since O'Loghlen had hardly said anything during their sessions. Mrs. Berthon Waters was a New Zealander who had been active in the Labour Party there, which had just established the first welfare state in the English-speaking world. MacBride was very impressed with her views.

The minority report advocated a Keynesian policy of state intervention and investment to develop the productive resources of the country, create employment and improve living standards. It also suggested breaking the link with sterling. In private, de Valera appeared sympathetic to their proposals but he eventually rejected them in favour of the rigidly orthodox majority report. MacBride believes de Valera was under the thumb of the intensely conservative Department of Finance. He once told MacBride that he knew nothing about economics and in the field of financial policy always did whatever the Department of Finance told him.

The Banking Commission experience confirmed that whatever social radicalism Fianna Fail had professed in the early 1930s had been abandoned. Many of the ideas in the minority report were to reappear later, however, in the programme of Clann na Poblachta. Despite this episode, MacBride didn't get directly involved in politics at this time. It was only two years since the collapse of his last political venture on behalf of the IRA, Cumann Poblachta na hEireann. Besides, he had qualified as a barrister in 1937 and had a career to make for himself, which he did with great success. He took only six years, the shortest time ever, to become a Senior Counsel.

There was another reason as well for not becoming directly involved in politics. With the approach of another World War, it was no time to challenge de Valera, whose policy of neutrality MacBride strongly supported, despite his battles with the government over the internment and execution of republican prisoners. Indeed in March 1944, when there was a crisis over a US demand that the government expel the German and Japanese diplomats in Dublin, MacBride wrote to de Valera praising his handling of the crisis and offering his own services if he could be of any assistance to the government.

By the end of 1945, however, there was no longer any fear that to challenge de Valera might undermine the neutrality of the state. Fianna Fail had been in power for 13 years. Their radicalism had evaporated. Their drive to dismantle the Treaty had ended with the 1937 Constitution and the return of the Treaty ports. They had done nothing about partition. The 'slightly constitutional' republican party had maltreated and executed republican prisoners. The party which had won the votes of workers and small farmers was becoming identified with businessmen and industrialists. It was beginning to be tainted with jobbery and corruption. Besides, the South had suffered great hardship and poverty during the war. Everything had stagnated except the emigration figures and Fianna Fail showed little sign of doing anything about it.

There was growing discontent but no one to articulate it. Fine Gael had been declining steadily since 1932 and was down to 30 seats in the Dail and anyway Fine Gael, with its bourgeois and big farmer image and Blueshirt past, could not win over the disgruntled industrial and white collar workers, and small farmers who had supported Fianna Fail. Nor could the Labour Party which lacked a record on the national question, was dominated by full-time union officials and had just split in two. A small farmers' party had already been set up but the big gap was for a party to win over urban workers and Fianna Fail's traditional republican support. That gap was about to be filled.

By the end of the war the IRA was at its lowest ebb ever, crushed by a combination of de Valera's repression and its own lack of direction. Many republicans, both of MacBride's generation and those who had been jailed or interned during the war, felt that physical force republicanism had come to the end of the road. A number of them had been active in working for the release of the remaining republican prisoners and in July 1946 they announced the formation of a new political party, Clann na Poblachta.

The dominant figure was Sean MacBride but the provisional executive sounded like a roll-call of the 1930s IRA. It included another former Chief of Staff, Michael Fitzpatrick, and two former Adjutants General, Donal O'Donoghue and Jim Killeen. It included too the widow of Austin Stack, who had been the only anti-Treaty member of the original Dail Cabinet not to join Fianna Fail. Not all the new party's members were ex-IRA, however. Noel Hartnett, a compelling speaker and able organiser, had been a member of the national executive of Fianna Fail. He exemplified the Clann's hopes of eating into Fianna Fail's support. And Captain Peadar Cowan had served in the Free State army during the Civil War, then joined the Labour Party and more recently had been identified as a militant socialist, being expelled from the Labou party in 1945.

The Clann's policies were republican and radical, though social reforming rather than militantly socialist. Clann na Poblachta aimed to declare the South a Republic and break the last links with Britain. And it aimed to take a number of initiatives over the Northern problem, including launching an international propaganda campaign against partition and giving Northerners representation in the Oireachtas. On social and economic issues it called for productive investment and public works such as afforestation and land reclamation to create jobs; a programme of slum clearance; increased social welfare benefits and a minimum wage; and the building of hospitals. It also sought an end to the link with sterling and the recall of Irish money invested in London to finance some of this programme.

The Clann's policies were republican and radical, though social reforming rather than militantly socialist. Clann na Poblachta aimed to declare the South a Republic and break the last links with Britain. And it aimed to take a number of initiatives over the Northern problem, including launching an international propaganda campaign against partition and giving Northerners representation in the Oireachtas. On social and economic issues it called for productive investment and public works such as afforestation and land reclamation to create jobs; a programme of slum clearance; increased social welfare benefits and a minimum wage; and the building of hospitals. It also sought an end to the link with sterling and the recall of Irish money invested in London to finance some of this programme.

The Clann was not secularist however. It stressed that its primary aim was to establish an economic and social system based upon Christian social and economic principles, a declaration that may have reflected the bitter experiences of MacBride and some of the other founding members when the bishops denounced Saor Eire and the Republican Congress in the 1930s. The new party caught the mood of the moment, attracting all who wanted change and reform after the grim wartime years and especially recruiting youth. It got an extra boost from a long drawn-out teachers' strike in Dublin in 1946 which embittered a lot of teachers against Fianna Fail and brought them into the Clann. By the time of its first Ard Fheis in November 1947 the new party was claiming to have 10,000 members in 252 branches throughout the country, including some in the North.

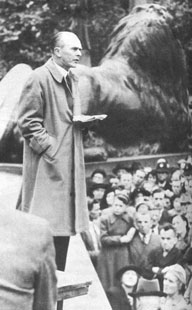

In October 1947 there were three by-elections in Co. Dublin, Tipperary and Waterford. In their first electoral outing the Clann contested all three, putting up MacBride in Co. Dublin. They won two of the three seats, with MacBride easily defeating Tommy Mullins, the general secretary of Fianna Fail, and Patrick Kinnane, another former IRA man, winning more narrowly in Tipperary. MacBride now became a national figure and the Clann appeared to pose a real threat to Fianna Fail. De Valera decided to nip the challenge in the bud and called a general election for February 1948.

The Clann threw itself enthusiastically into the campaign and it now had a new and compelling issue to raise. Late in 1947 a young doctor called Noel Browne joined the party, brought in by Noel Hartnett, who became director of elections for the 1948 contest. Noel Browne's parents and sister had died of tuberculosis and he had suffered from it himself. He had no experience of politics but was dedicated to eradicating TB, which then wreaked terrible havoc, especially among the poor, and which had been almost totally neglected by the government. Browne's plans for stamping out TB and improving hospitals gave the Clann an important boost.

The Clann nominated 93 candidates - more than Fine Gael and enough to form a government. The list included some very famous republican names - Mrs. Kathleen Clarke, widow of Tom Clarke the 1916 leader, and a former Fianna Fail Senator; MJ. Barry, a brother of Kevin Barry; Ruadhri Brugha, son of Cathal Brugha - as well as MacBride's colleagues of the 1930s IRA. But it included some oddities as well, such as Aodh de Blacam, an Irish Press journalist and former Fianna Fail member, and Dr. J.P. Brennan, both of whom had supported Franco during the Spanish Civil War. There was also a number of candidates from pro Treaty or non-political backgrounds. It was a mixed bag, showing signs of having been hastily cobbled together and suggesting that the Clann might have difficulty holding together under strain.

The Clann's campaign was imaginative and original. They made a film which was shown around the country

in cinemas or against whitewashed gable walls and they used an aeroplane to tow election banners. Their basic slogan was 'Put Them Out'. MacBride's election tour was like a triumphal progress. The atmosphere was electric and some members thought they would win a majority. MacBride himself thought until the last fortnight that they would get between 30 and 40 seats. The press was very hostile however, especially the Irish Press and Fianna Fail ran an assiduous 'Red' smear campaign against the Clann. In the closing days of the campaign the voters seemed to get cold feet about a party which was still only 18 months old.

The results were well below the Clann's heady expectations but they had done quite well getting 170,000 first preferences or 13% of the total, with MacBride himself topping the poll in Dublin South West. The quirks of PR, however, gave them only 10 seats instead of the 19 they might have expected. They had done particularly well in the Dublin area where they won six seats and narrowly missed a couple more. Among those elected in Dublin was

Noel Browne. The overall result was inconclusive. Fianna Fail had lost eight seats and were six short of an overall majority. The combined opposition could defeat them. Fine Gael, desperate for power after 16 years out of office, suggested a coalition government and invited the other party leaders to talks. Fianna Fail made clear they were not interested in coalition with anyone. MacBride accepted the Fine Gael invitation and so found himself sitting down with General Richard Mulcahy, who as Commander in Chief of the Free State army during the Civil War had been responsible for the execution of MacBride's cell-mate, Rory O'Connor, and many other republicans.

During the election MacBride had spoken of a possible alliance between Clann na Poblachta and the other parties of the underdog, Labour, National Labour (an ITGWU inspired breakaway from Labour), and Clann na Talmhan. At the height of the campaign a majority for such an alliance seemed feasible. Coalition with Fine Gael,- the victors in the Civil War and the Blueshirts of only a decade earlier, was a different matter. No one in the Clann seems to have envisaged a situation where Fianna Fail could only be put out by an alliance with Fine Gael. Fine Gael were prepared to be very accommodating, however. They were prepared to propose John A. Costello, a barrister with no Civil War record, for Taoiseach instead of the unacceptable Mulcahy. And they were prepared to accept a lot of Clann na Poblachta's programme of reforms.

MacBride's attitude was pragmatic rather than militant or revolutionary. He supported the idea of an Inter-Party government, arguing that the Clann had campaigned on a platform of putting Fianna Fail out and so they should do just that and seize the chance of implementing some urgently needed reforms. Moreover the idea of an alliance with Fine Gael seemed a little less obnoxious given that Fine Gael would actually be in a slight minority vis-a-vis Clann na Poblachta and the other groups supporting the new government - Labour, National Labour, Clann na Talmhan and a number of Independents.

Besides, the Clann had tried during the election to attract votes from people with a non-republican or even pro-Treaty background, saying: "We don't care what colour shirt you wore". Coalition with Fine Gael would demonstrate that they really meant this. And MacBride wanted to show that the Clann could play a responsible part in government, so as to answer charges of irresponsibility made against them during the election.

Joining a government led by the former Blueshirts was still a bitter pill for many Clann members to swallow, however. It took lengthy meetings of the party's Standing Committee and Ard Comhairle to thrash out their position. The voting showed their dilemma. They voted, with only one against, to oppose de Valera as Taoiseach. They agreed unanimously to join a coalition if it could be led by MacBride or by William Norton, the leader of the Labour Party. That wasn't feasible, however, so they had to grapple with the question of a Fine Gael leader.

A motion not to take office under any Fine Gael nominee was defeated by 18 votes to 12 by the Ard Comhairle. On the proposal of Noel Hartnett, seconded by MacBride, the Standing Committee voted more narrowly to accept either Sir John L. Esmonde or John A. Costello as Taoiseach. Esmonde got one vote more than Costello but he wasn't acceptable to his own party. The Clann's republican background was stressed by a unanimous vote to review their position after one month if all Republican prisoners had not been released. Even so the decision to enter the government was nof popular with some of the Clann's grass-roots. There were accusations of opportunism and some resignations from the party. One of them came from a young Limerickman called Sean South, who was to die in an IRA attack on a Fermanagh RUC barracks eight years later. And presumably some of the Clann's more republican-minded supporters began to have doubts from then on.

A motion not to take office under any Fine Gael nominee was defeated by 18 votes to 12 by the Ard Comhairle. On the proposal of Noel Hartnett, seconded by MacBride, the Standing Committee voted more narrowly to accept either Sir John L. Esmonde or John A. Costello as Taoiseach. Esmonde got one vote more than Costello but he wasn't acceptable to his own party. The Clann's republican background was stressed by a unanimous vote to review their position after one month if all Republican prisoners had not been released. Even so the decision to enter the government was nof popular with some of the Clann's grass-roots. There were accusations of opportunism and some resignations from the party. One of them came from a young Limerickman called Sean South, who was to die in an IRA attack on a Fermanagh RUC barracks eight years later. And presumably some of the Clann's more republican-minded supporters began to have doubts from then on.

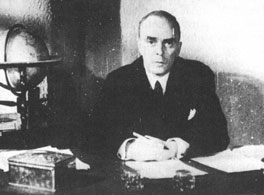

On February 18 1948 the first Inter-Party government took office. It announced a 10-point programme, including measures to increase agricultural and industrial production, the introduction of a comprehensive social security scheme, a major housing drive, and immediate steps to stamp out TB. Costello was Taoiseach and William Norton, the leader of the Labour Party, the second largest group in the coalition, became Tanaiste. Clann na Poblachta got two Cabinet posts. MacBride himself became Minister for External Affairs and Noel Browne became Minister for Health. Mac· Bride sought the External Affairs post because it would put him in charge of Anglo-Irish relations and enable him to raise the issues of the Republic, membership of the Commonwealth and partition. With his French upbringing, he was also very interested in European unity and wanted to involve Ireland in the movement towards a united Europe which was developing after the war.

Noel Browne's political career had been meteoric. He had been involved in politics for less than six months and he became a Cabinet Minister on his tirst day in the Dail. MacBride himself picked Browne to join the Cabinet with him and there was some grumbling in the Clann over the promotion of such a newcomer. MacBride argued that Browne's plans to eradicate TB had won widespread support, a drive against the disease was a matter of urgency, and Browne was the obvious one to lead it. He also hoped that Browne, with his non-republican background, would dilute the Clann's image as an IRA party and help win wider support.

One of the new government's first actions helped quieten the rumblings among the Clann's more republican supporters. On March 5 they decided to release Tomas MacCurtain, whom MacBride had saved from the gallows by a matter of hours in 1940, and Harry White, whom he had got off a capital charge in 1946. Within the next few weeks they released all the remaining republican prisoners, including a young Dubliner called Brendan Behan. MacBride stresses that the Inter-Party government was the first administration since 1922 which had no political prisoners in jail throughout its term of office.

The motley assortment of Ministers in the new Cabinet could have proved an explosive mixture but the more prominent ex-Blueshirts like Mulcahy and Dr. T.F. O'Higgins, brother of Kevin O'Higgins, were given less controversial departments (Education and Defence) and didn't play a major role in the government. Indeed MacBride says that, though Mulcahy was still the official leader of Fine Gael, his party colleagues paid very little attention to him. In general the Cabinet worked quite well together, at least until the close of 1950.

MacBride had few direct dealings with Mulcahy but on one occasion, Good Friday 1948, Mulcahy called him urgently to his office. He was acting as Minister for Justice while Sean MacEoin was on holiday. He told MacBride the Gardai had been warned by the RUC that some Northern IRA men planned to shoot him (MacBride) - a fairly unlikely story. The Gardai wanted him to have an armed escort but he refused. A few days later, however, guards left a revolver and a box of ammunition at Roebuck House for him. When he checked them later he found the ammunition was the wrong calibre for the gun.

The Inter-Party government lasted just three years and is popularly remembered for two things in particular: the declaration of a Republic in 1949 and the Mother and Child scheme in 1951. In fact, it saw a lot of innovations and, after the stagnation of the war years and their aftermath, it seemed at first highly dynamic and energetic. The two Clann na Poblachta Ministers had an impact much greater than their numbers warranted. Browne threw himself with great energy into campaigns to eradicate TB and build hospitals. The money came from the Hospitals Sweepstake. Previous governments had invested the returns from the Sweepstake and used only the interest for hospital buildings. Now MacBride and Browne persuaded their colleagues, not only to use the capital, but even to mortgage the future income from the Sweepstake. As a result, spending on hospital construction soared from about £200,000 in 1947 to almost £3,000,000 in 1951 and the number of beds available to TB patients increased from a little over 2,000 to 8,000.

Browne also launched radiography and innoculation services to help stamp out TB. It was the beginning of the end for the disease and within a few years it had virtually disappeared. A number of general hospitals were also built and Browne started a national blood transfusion service. He worked so hard that his health broke down in 1950 but he recovered after a few months.

MacBride, as leader of the Clann, was anxious to influence government policy on many areas outside his own Department, especially in the area of finance and economic development. His choice of Ministry was lucky. The Marshall Aid scheme was just getting under way, with the US making massive grants and loans to aid Western European post-war recovery - and, of course, to create markets for US goods and extend their sphere of influence. It fell to the Department of External Affairs to conduct the negotiations with US officials and draw up a programme of measures for which the US funds would be used.

MacBride took full advantage of this to propose a programme of public investment to stimulate industrial development and promote land drainage, afforestation, improvements in fishery and harbour facilities and the expansion of agricultural education - all part of the Clann's programme. His hand was strengthened because the government had agreed to join the newly formed Organization for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC) and he had become one of its Vice-Presidents. The US had decided to channel all Marshall Aid funds through the OEEC and MacBride, as the representative of a small country which presented no threat to the major OEEC members, was made negotiator for the whole group. He needed the extra muscle this gave him because, while most of his Cabinet colleagues accepted his proposals, he faced a tough battle with the Department of Finance. After 1922 the Department of Finance had modelled itself rigorously on the British Treasury with its role of watchdog on public spending and guardian of economic orthodoxy and conservatism. The Cosgrave government with its obsession with cutting public expenditure had encouraged this trend and de Valera had done nothing to change it.

MacBride took full advantage of this to propose a programme of public investment to stimulate industrial development and promote land drainage, afforestation, improvements in fishery and harbour facilities and the expansion of agricultural education - all part of the Clann's programme. His hand was strengthened because the government had agreed to join the newly formed Organization for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC) and he had become one of its Vice-Presidents. The US had decided to channel all Marshall Aid funds through the OEEC and MacBride, as the representative of a small country which presented no threat to the major OEEC members, was made negotiator for the whole group. He needed the extra muscle this gave him because, while most of his Cabinet colleagues accepted his proposals, he faced a tough battle with the Department of Finance. After 1922 the Department of Finance had modelled itself rigorously on the British Treasury with its role of watchdog on public spending and guardian of economic orthodoxy and conservatism. The Cosgrave government with its obsession with cutting public expenditure had encouraged this trend and de Valera had done nothing to change it.

By 1948 the Department of Finance had established its hegemony over all the other Departments and collaborated very closely with the British Treasury, so closely in fact that senior officials in Finance used first names in correspondence with Treasury officials but not with their colleagues in other Irish Departments. On the insistence of the Department of Finance, Irish civil service pension funds were invested in London securities instead of being used for productive purposes at home.

The Finance officials were less than enthusiastic about Marshall Aid. They feared it might disturb their cosy relationship with the Treasury and the Bank of England and they thought it. might lead to undue dependence on foreign borrowing and, by encouraging dollar imports, upset the balance of trade. If they had to accept Marshall Aid, they wanted it to be used to payoff the public debt (i.e. basically for accounting purposes), instead of for MacBride's schemes for promoting growth and employment. Ironically, one of the Department of Finance's toughest memos opposing the idea of productive state spending was written by a rising young official called T .K. Whitaker, later the author of Lemass's Programmes for Economic Expansion.

MacBride was friendly with the US ambassador, George Garrett, and enlisted his support to say that the Marshall funds should be used to stimulate growth. Finance didn't give up easily however, and on one occasion MacBride returned from a trip abroad to find that, behind his back, senior officials from Finance had taken Garrett out to dinner and tried to persuade him to veto MacBride's plans. Garrett was unimpressed however and promptly reported the approach to MacBride. MacBride won that battIe. The government did accept Marshall Aid - S 150 million worth of it - and used it for productive investment, including a commitment to plant 25,000 acres of trees per year which has been maintained up to now. (Reafforestation is a pet topic of MacBride's.)

And in connection with the Marshall Aid scheme, MacBride's Department drew up a Long-Term (Economic) Recovery Programme which was accepted by the government and published in January 1949 - the first attempt at an overall economic plan since the establishment of the state. MacBride got government approval as well for efforts to diversify Irish trade and lessen its dependence on Britain. He had a hand in the decisions to set up Coras Trachtala, to stimulate exports to the US, and the Industrial Development Authority, to promote new industry. There were social reforms too, urged by the Labour Party as well as Clann na Poblachta. Old age pensions and social welfare benefits were increased substantially and the number of houses built under government-aided schemes jumped from 1,460 in 1947 to 12,048 in 1950.

MacBride didn't get his way on everything though. It was Clann policy to break the Irish pound's link with sterling and the opportunity came when Britain devalued in September 1949. MacBride urged a break but was defeated. He was defeated as well when he tried to block the re-appointment of Joseph Brennan, the highly conservative Governor of the Central Bank, in 1950. These reverses demonstrated that there were limits beyond which Fine Gael, traditionally the party of the big farmers, businessmen and professional classes, would not go.

The Clann was, of course, committed to declaring a Republic and on that issue they did get their way, indeed it became the government's best-known achievement. MacBride discounts the melodramatic version of that story, i.e. that Costello announced his intention of declaring a Republic out of pique after being insulted by the Governor General of Canada, Earl Alexander, a member of a prominent Unionist family from Co. Tyrone. MacBride says a consensus had quickly developed in the Inter-Party government on the question and both he and the Tanaiste, William Norton, had indicated clearly in the Dail in July and August 1948 that they were thinking of repealing de Valera's External Relations Act which retained the state's last links with the British Crown. De Valera had rather grudgingly replied that they would get no opposition from Fianna Fail.

Costello was due to speak at a meeting of the Canadian bar association in September 1948 and prepared a speech which criticised the External Relations Act. It was regarded by the Cabinet as giving due warning of the government's intentions to Britain and the Commonwealth and, for that reason, the full text was discussed and approved by the Cabinet beforehand, the only speech to be treated that way. At home the Sunday Independent saw the significance of Costello's Canadian speech and came out with a headline 'External Relations Act To Go'. Costello was due to give a press conference in Canada and, knowing he would be questioned about the Independent's story, decided to go ahead and reply that his government intended to repeal the act, leave the Commonwealth and declare a Republic. MacBride maintains that the Cabinet members in Dublin were surprised only by the timing of the announcement, not by its substance.

When Costello returned home the Republic of Ireland Bill was quickly introduced and was passed by the end of 1948. The Republic of Ireland was formally inaugurated on Easter Monday 1949. One of Maud Gonne's last public appearances was to accompany her son to the ceremonies marking its inauguration. Clann na Poblachta was also committed to taking action on partition and the repeal of the External Relations Act focused attention on the issue because the British Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, promptly reaffirmed British support for the Northern government. The Northern Prime Minister, Sir Basil Brooke, called a general election for February 1949. At MacBride's suggestion Costello called a conference of the leaders of the main Southern parties at the Mansion House in Dublin and they in turn called a nationwide collection to raise funds for anti-partition can· didates in the North.

The collection brought in about £46,000 and was used to support all candidates who opposed partition, including some Protestant Labour nominees. With singular lack of foresight, however, the collection had been taken up outside churches on a Sunday, in the normal Southern manner. The contest was promptly dubbed the 'Chapel-gates election' by the Unionists, who used the issue to revive the slogan of 'Rome Rule' and won an increased majority at Stormont after a bitter and violent campaign. The Mansion House committee still had some money left over after the election and they used it to finance a series of anti-partition pamphlets and two books, 'The Indivisible Island' by Frank Gallagher, which collected a lot of information on discrimination and gerrymandering, and 'The Finances of Partition' by Labhras 0 Nuallain. Some of the pamphlets, which were distributed abroad by the Irish embassies, were written by a bright young civil servant in the Department of External Affairs called Conor Cruise O'Brien.

MacBride himself intervened in the Westminster elections in the North in 1950, both he and Noel Browne speaking in support of the veteran Northern Nationalist, Cahir Healy, in the Fermanagh-South Tyrone constituency. The Mansion House fund was also used to send Northern nationalists on speaking tours in the US while MacBride constantly raised the question of partition at the newly-established Council of Europe and with the US and European governments. There was sympathy for the cause of Irish unity in Europe and several US state legislatures and a Congressional committee passed resolutions opposing partition, but it had little practical effect other than to sustain the hopes of the Northern nationalists. Indeed the British parliament, in its legislation consequent on the repeal of the External Relations Act, reinforced the constitutional position of the North.

It had been an inauspicious time to raise the issue. Britain was still resentful about the South's neutrality during the war and acutely conscious of how useful the North had been during the conflict. A British Cabinet document of the time stressed "the strong strategic arguments for the retention of the friendly bastion of the six counties". And the British ambassador, Lord Rugby, told MacBride that the British government regarded the Belfast shipyard as a vital facility in wartime, even though it was a financial liability in peacetime. Besides, the Cold War was developing and the US, whose support Dublin sought to enlist, was unlikely to antagonise its closest ally for the sake of a small neutral state, like the Republic. Another reason why the anti-partition campaign didn't have more effect, however, may well have been the quiescence of the Northern minority. Still demoralised after the troubles and depression of the 1920s and 1930s, they simply weren't creating enough disturbance in the North to make it necessary for the British to do something about the place.

It had been an inauspicious time to raise the issue. Britain was still resentful about the South's neutrality during the war and acutely conscious of how useful the North had been during the conflict. A British Cabinet document of the time stressed "the strong strategic arguments for the retention of the friendly bastion of the six counties". And the British ambassador, Lord Rugby, told MacBride that the British government regarded the Belfast shipyard as a vital facility in wartime, even though it was a financial liability in peacetime. Besides, the Cold War was developing and the US, whose support Dublin sought to enlist, was unlikely to antagonise its closest ally for the sake of a small neutral state, like the Republic. Another reason why the anti-partition campaign didn't have more effect, however, may well have been the quiescence of the Northern minority. Still demoralised after the troubles and depression of the 1920s and 1930s, they simply weren't creating enough disturbance in the North to make it necessary for the British to do something about the place.

There were some interesting spin-offs from the antipartition campaign. One was the Irish News Agency. At the time all news from Ireland went through the correspondents of the British papers or the British-owned Reuters news agency. This militated against good coverage of the anti-partition campaign and presented a poor overall impression of Ireland. MacBride, as a former journalist, was very conscious of this and got the government to set up an agency to publicise, not only the case against partition, but Irish affairs generally. It was an interesting experiment and employed a number of able young journalists like Douglas Gageby, Donal Foley, John Healy, Michael Finlan, and Gerry Mulvey, while the head of the agency was the author of the anti-partition pamphlets, Conor Cruise O'Brien.

Another spin-off was that in 1949, on the initiative of Cahir Healy, MacBride had two secret meetings with Sir Basil Brooke at Stormont. He also had a number of private meetings with W.W.B. Topping, the Unionist Chief Whip and later Minister of Home Affairs. Nothing came of the meetings except that they revealed a little about the public and private faces of Ulster Unionism. Brooke, noted for his virulently sectarian speeches in the past, was polite and courteous, as befitted a member of the landed gentry, though distant. Topping became quite friendly and took to visiting MacBride in Dublin, though it turned out he was more interested in the good food and wine provided than in political negotiations. He used to get drunk and sing rebel songs and eventually word of his visits leaked out. One day a very worried Topping rang MacBride to say he was going to be asked a question at Stormont about the visits and would have to deny meeting MacBride at all. He made no more clandestine trips to Dublin.

These were extremely busy years for MacBride. His primary responsibility in the government was, of course, External Affairs, which took him abroad a lot and he met most of the leading politicians of the time including the US President, Harry Truman, the founders of the EEC, Robert Schuman and Jean Monnet and the British leaders, Attlee and Churchill. He got on well with Attlee, the Labour Prime Minister, who seemed sympathetic to Irish unity, despite his public support for the Northern government. MacBride felt he was frightened of Churchill, however, and Attlee told hm that if he [MacBride] could win over Churchill the Labour government would be able to adopt a more sympathetic policy.

Attlee arranged a private dinner for the three of them. It was not a success. At the beginning Churchill said gruffly to MacBride: "I believe your father and I were both in South Africa in 1900 - but on opposite sides". MacBride agreed. Churchill continued: "It appears that you and I were both at the Anglo-Irish conference in 1921, but still on opposite sides". MacBride concurred. "It seems we are fated to always be adversaries", concluded Churchill. "So much the better because on the Irish question I have my loyalties. I cannot let down my Unionist friends in Ulster". He said no more for the rest of the dinner.

MacBride's most lasting achievements in foreign policy concerned NATO and the Council of Europe. The government was approached by the US in January 1949 to join NATO, which was then being set up, and there was continuing US pressure over the next two years to get the Republic into the alliance. Eventually in February 1951 the US warned that in future Marshall Aid would be tied to US defence policy and in 1952 US aid to Ireland ended. There was support in Fine Gael for joining NATO but MacBride got government agreement to stay out on the grounds that membership would involve alliance with the power responsible for partition. They also agreed to try to use US anxiety to get Dublin involved to get the US to pressurise Britain over the North.

The government's position was summed up in a note from MacBride to the US ambassador in February 1949. He said: "Any military alliance with ... the state that is responsible for the unnatural division of Ireland, which occupies a portion of our country with its armed forces and which supports undemocratic institutions in the northeastern corner of Ireland, would be entirely repugnant and unacceptable to the Irish people". Any Dublin government which entered into such an alliance would run the risk, in a crisis, "of civil conflict within its own jurisdiction". The document agreed with the general aims of NATO, however, in language which reflected the Cold War atmosphere of the time and contrasted sharply with the rhetoric of Saor Eire and the anti-imperialist conferences of MacBride's earlier days. It stressed Ireland's commitment to "Christian civilisation and the democratic way of life" andsaid that because of this Ireland had remained singularly immune from the spread of Communism. It held open the possibility that, if partition was ended, Ireland might join the alliance.

At the time MacBride was pragmatic about the question. This approach satisfied Fine Gael and other elements of the coalition like National Labour and Clann na Talmhan who were, if anything, even more anti-Communist. Partition was not ended so the question of joining NATO was not posed. Fianna Fail backed the government's policy and continued it when they returned to office so the Republic stayed out of the alliance. To-day MacBride is particularly glad of that, though his attitude to NATO is now different and much more hostile. He is totally opposed to membership, even by a united Ireland, citing three main reasons: NATO's commitment to nuclear weapons; -its support for undemocratic and colonialist regimes, notably in South Africa; and his belief that the division of the world into power blocs accelerates the arms race and increases the likelihood of a world war.

MacBride played a leading part in the setting up of the Council of Europe in May 1949 and the Republic was one of the 10 founder members. MacBride himself was elected President of the Committee of Foreign Ministers which acted as the Council's executive body. One of the first tasks of the Council was one in which he was particularly interested: drawing up a Convention of Human Rights and machinery to enforce it. He was one of the signatories of the European Convention when it was adopted in 1950 and it remains perhaps his proudest achievement. While MacBride was preoccupied with international questions trouble was brewing at home, however. There was a Gilbertian dispute in Baltinglass, Co. Wicklow, towards the end of 1950 when the Labour Minister for Posts and Telegraphs, James Everett, appointed one of his supporters as sub-postmaster, by-passing a local family who had held the post for years. The government became a laughing stock when it tried to use the army to counter local passive resistance and eventually Everett's nominee resigned. The dispute caused rumbles in Clann na Poblachta which had promised to stamp out just such petty jobbery.

But the real trouble was over the Mother and Child scheme. Noel Browne had spent the latter part of 1950 drawing up a scheme for free, no means test, medical treatment for mothers and children, a scaled-down version of the National Health Service just introduced in Britain. He was already having trouble with the intensely conservative medical profession when, in October 1950, the Catholic hierarchy wrote to the government complaining about the scheme. The bishops' basic objections were that the scheme represented a big expansion of state intervention in the everyday lives of the citizens and that there was no means test. The Catholic church at the time was bitterly opposed to any expansion of the role of the state and took up a position rather like that of the 19th century Poor Law. It held that the state should only intervene in social questions to relieve those in dire need and that a means test was necessary to single out the really poor.

The bishops seemed blissfully unaware of the extent of poverty in the country. In a revealing phrase they said that it would be wrong for the state "to deprive 90% of necessitous parents of their rights (by bringing them into the scheme) for the sake of 10% necessitous or negligent parents". Browne himself was interviewed by Dr. John Charles McQuaid, the Archbishop of Dublin and two other bishops the day after the hierarchy's letter was sent. He apparently promised to make some changes to meet their objections and there the matter rested until March 1951 when he sent the bishops copies of the draft regulations for the scheme. The bishops were not at all satisfied and on April 5, McQuaid wrote to Costello, the Taoiseach, saying: "The hierarchy must regard the scheme proposed by the Minister for Health as opposed to Catholic social teaching".

The bishops seemed blissfully unaware of the extent of poverty in the country. In a revealing phrase they said that it would be wrong for the state "to deprive 90% of necessitous parents of their rights (by bringing them into the scheme) for the sake of 10% necessitous or negligent parents". Browne himself was interviewed by Dr. John Charles McQuaid, the Archbishop of Dublin and two other bishops the day after the hierarchy's letter was sent. He apparently promised to make some changes to meet their objections and there the matter rested until March 1951 when he sent the bishops copies of the draft regulations for the scheme. The bishops were not at all satisfied and on April 5, McQuaid wrote to Costello, the Taoiseach, saying: "The hierarchy must regard the scheme proposed by the Minister for Health as opposed to Catholic social teaching".

McQuaid delivered the letter himself and discussed the question with Costello. The recently-released Cabinet papers reveal for the first time that Costello then and there undertook to accept the hierarchy's decision. He hadn't consulted his colleagues before giving this undertaking and the Cabinet did not discuss the letter until the next day. This raises the intriguing possibility that, had the Cabinet decided to go ahead with the scheme, Costello might have had to resign. The Cabinet didn't decide to go ahead, however. None of its members was prepared for a clash with the hierarchy, not even MacBride or the Labour Ministers. MacBride was the only one to have his comments recorded. (The Cabinet Minutes did not record discussion, only decisions taken.) He was, as usual, pragmatic and had an eye to the immediate political effects of the controversy.

He said: "It is of course impossible for us to ignore the views of the hierarchy. Even if, as Catholics, we were prepared to take the responsibility of disregarding their views, which I do not think we can do, it would be politically impossible to do so. We must therefore accept the views of the hierarchy in this matter".

He suggested compromise and the entire Cabinet, apart from Browne himself, agreed to drop Browne's scheme and try to draw up one which would accept the principle of a means test but set the threshold sufficiently high to bring most families within its scope - a figure of £1,000 per annum, a very substantial sum then, was suggested. The scheme was to be "in conformity with Catholic social teaching" .

Things had gone too far for compromise, however. So far all this activity had been behind closed doors but rumours were spreading. The trade union congress, the Dublin Trades Council, the Irish Housewives' Association came out in support of the no means test scheme. Browne, who had indicated that he would accept the hierarchy's veto and resign, now showing signs of hanging on and fighting the issue. On April 10 MacBride asked Browne to resign, anticipating that Costello was about to sack him. In fact the Cabinet papers reveal that Costello had already drafted a letter seeking his resignation, though MacBride didn't know that at the time.

Browne responded very bitterly, accusing MacBride of hypocrisy and expediency and then released the whole correspondence about the Mother and Child scheme to the press. It created a sensation, bringing the hierarchy's intervention out in the open. Browne resigned from the government and from Clann na Poblachta. Another Clann TD, Jack McQuillan, resigned in support of him. There was an acrimonious clash in the Dail between Browne and his former colleagues. None of the protagonists covered themselves with glory on the subject of Church state relations. Costello said: "I, as a Catholic, obey my church authorities and will continue to do so ... " Mac Bride said: ''Those of us in this House who are Catholics ... are, as such, of course bound to give obedience to the ruling of our church and our hierarchy". Even Browne said:

"I, as a Catholic, accept unequivocally and unreservedly the views of the hierarchy on this matter".

Fianna Fail said nothing, watching with satisfaction as their opponents lacerated each other. Only one TD, Captain Peadar Cowan, who had resigned from the Clann earlier, on a separate issue, challenged the right of the hierarchy to intervene on such an issue and argued that they were usurping the rights of the Dail and the voters. The whole affair was a disastrous set-back for the cause of the separation of church and state in Ireland and it did not help the anti-partition cause either. It was seized on with glee by the Ulster Unionists as confirmation that Home Rule did mean Rome Rule. In the process it was hardly noticed that the Unionists themselves had given way to the Protestant churches in the North in a similar conflict over education two years earlier.

MacBride still maintains that a compromise could have been reached if it had not all come out in the open. He claims that Browne provoked the crisis as part of an ongoing conflict within Clann na Poblachta. Browne was greatly influenced by Noel Hartnett, the former Fianna Fail member who had run the Clann's 1948 election campaign. Relations between Browne and Hartnett on the one hand and MacBride on the other had become very strained by late 1950. Hartnett had become increasingly critical of MacBride's leadership saying the party was becoming opportunist and unprincipled. MacBride, on the other hand, felt Hartnett was embittered because MacBride had not nominated him to the Senate when he narrowly failed to win a Dail seat in 1948. Hartnett resigned from the Clann in February 1951, before the Mother and Child crisis but he remained in contact with Browne.

In November 1950 MacBride had had a remarkable discussion with Browne over dinner in the Russell Hotel, during which, he says, Browne threatened that if he didn't follow the advice of Hartnett and Browne, the latter would pick an issue on which to bring down the government and split the Clann. MacBride claims that this is what happened over the Mother and Child scheme. The crisis certainly had that effect. Tensions had been developing in the Inter-Party government before the bishops intervened. There was the Baltinglass affair and some Clann na Talmhan TDs defected in a dispute over milk prices. It was believed some Fine Gael TDs were distinctly unhappy about the Mother and Child scheme because it would cost too much and their friends in the medical profession didn't like it - the Cabinet papers show that the IMA and individual doctors lavished praise on Costello after the Dail debate on the crisis.

The coalition may have been beginning to fragment anyway. The list oflong-overdue and readily-agreed reforms resulting from the years of war-time stagnation was nearly exhausted and the inherent contradictions in the alliance were beginning to show. The Mother and Child crisis exploded the contradictions and within a month the government went to the polls. Clann na Poblachta was in disarray. The Standing Committee and Ard Comhairle had backed MacBride but two TDs (Browne and McQuillan) had resigned, joining Cowan, who had left earlier. A number of councillors had resigned as well and a fourth TD, J.P. Brennan, defected to the Labour Party just before the election. When the Clann faced the electorate, 40% of the TDs elected in 1948 had left. The party put up only 26 candidates in the election, compared with 93 in 1948.

The coalition may have been beginning to fragment anyway. The list oflong-overdue and readily-agreed reforms resulting from the years of war-time stagnation was nearly exhausted and the inherent contradictions in the alliance were beginning to show. The Mother and Child crisis exploded the contradictions and within a month the government went to the polls. Clann na Poblachta was in disarray. The Standing Committee and Ard Comhairle had backed MacBride but two TDs (Browne and McQuillan) had resigned, joining Cowan, who had left earlier. A number of councillors had resigned as well and a fourth TD, J.P. Brennan, defected to the Labour Party just before the election. When the Clann faced the electorate, 40% of the TDs elected in 1948 had left. The party put up only 26 candidates in the election, compared with 93 in 1948.

There was none of the enthusiasm of 1948. Those who had seen the Clann as a force for radical change were dismayed by MacBride's acceptance of the bishops' veto. Republican sympathisers and former Fianna Fail suppor ters had been alienated by the alliance with Fine Gael. The result was a disaster. The Clann's vote slumped from 170,000 first preferences (13%) in 1948 to 54,000 (4%). Only two candidates were elected, MacBride himself and John Tully in Cavan. MacBride's own vote dropped from 8,648 first preferences in 1948 to 2,853 and he was elected on the last count. By contrast Browne, McQuillan and Cowan were elected fairly easily and another Browne supporter, Dr. French O'Carroll was elected in MacBride's own constituency. Some of the voters seemed to be thumbing their noses at the bishops. Fianna Fail returned to power with the aid of Browne and his supporters - Browne later joined Fianna Fail for four years - but the real gains in the election were made by Fine Gael, who reversed their steady decline since 1932 and went up from 31 seats to 40. The Inter-Party government had helped to restore their credibility as a serious alternative to Fianna Fail and had even softened their Blueshirt image a little. It was to become a familiar trend with coalition governments.

The 1951 election was the end of Clann na Poblachta as a serious force. They put up 18 candidates in 1954 but got only 3.4% of the vote, though they gained a seat in North Kerry. They supported the second Inter-Party government on the basis of an agreed programme of social reforms and MacBride was offered a Cabinet post but refused because the Clann didn't want responsibility for government policy when it didn't have enough seats to be able to insist on changes. The little Clann group in that Dail made their mark in some unusual ways, however. One was by electing Liam Kelly to the Senate. Kelly was the leader of a breakaway Northern republican group called Saar Uladh which, unlike Sinn Fein and the IRA, recognised the Southern constitution. Kelly had been elected as an abstentionist MP for Mid-Tyrone in 1953 and was serving a jail sentence in the North for making a seditious speech when he was elected to the Senate. When he was released in August 1954 MacBride spoke at a welcome-home rally in his home village of Pomeroy which erupted into a major riot when the RUC baton-charged the crowd.

In November 1955 the military wing of Kelly's group attacked an RUC barracks in Roslea, Co. Fermanagh, in the first of a series of raids in the North which eventually led to the IRA launching their border campaign a year later. Saor Uladh did not admit their involvement at the time and ironically, though Kelly led the Roslea raid himself, he continued to attend the Senate for some time afterwards. MacBride was apparently not aware of the military side of his activities until later. The Clann's other unusual contribution to the 1954-57 Dail was to bring the Inter-Party government down. Unemployment and emigration soared in the mid-1950s and the Fine Gael Finance Minister, Gerard Sweetman, brought in a viciously deflationary budget in 1956. This, and the fact that the government began to clamp down on republicans when the IRA campaign started, was too much for the Clann and in January 1957 MacBride proposed a vote of no confidence which brought down the government.

This time the Clann got only 22,000 votes and only one seat - in Cavan, where John Tully had built up a steady personal vote. MacBride himself was defeated in Dublin South West. He was defeated again in by-elections in 1958 and 1959 and in the general election of 1961, which was his last electoral foray. Clann na Poblachta stayed in existence, but more for old times sake than anything else, until 1965 when it was formally wound up. Ironically John Tully was still a TD at the time - he finally lost his seat in 1969. In the meantime, MacBride's mother, Maud Gonne, had died-in 1953 at the age of 86. Increasingly frail in her last years, she had none the less written articles for Clann na Poblachta's journal and had made a number of radio broadcasts about her career. She had been pleased when her son, as Minister for External Affairs, brought home the remains of her old friend, W.B. Yeats, who had died in the south of France in 1939, though she was too weak to attend the reburial in Drumcliffe churchyard. She retained her interest in political prisoners and refugees to the very end.

Sean MacBride himself was about to embark on a whole new career. Since signing the European Convention on Human Rights in 1950, he had kept up his interest in the international protection of human rights. In 1957, when the new Fianna Fail government re-introduced internment, MacBride took the case of one of the internees, Gerry Lawless, to the European Commission on Human Rights. Eventually it became the first case to be heard by the new European Court when it was established in 1959. Lawless himself had been released shortly after the case was initiated. The court found against Lawless, but established the important principle that it could investigate for itself whether a state of emergency sufficient to warrant the use of internment or other exceptional measures existed in any country. It did not have to automatically accept the opinion of the government concerned. It was this principle which enabled it to condemn the regime of the Greek Colonels in 1970. And fear of condemnation by the European Court may well have inhibited Dublin Governments from reintroducing internment in the South since then.

Sean MacBride himself was about to embark on a whole new career. Since signing the European Convention on Human Rights in 1950, he had kept up his interest in the international protection of human rights. In 1957, when the new Fianna Fail government re-introduced internment, MacBride took the case of one of the internees, Gerry Lawless, to the European Commission on Human Rights. Eventually it became the first case to be heard by the new European Court when it was established in 1959. Lawless himself had been released shortly after the case was initiated. The court found against Lawless, but established the important principle that it could investigate for itself whether a state of emergency sufficient to warrant the use of internment or other exceptional measures existed in any country. It did not have to automatically accept the opinion of the government concerned. It was this principle which enabled it to condemn the regime of the Greek Colonels in 1970. And fear of condemnation by the European Court may well have inhibited Dublin Governments from reintroducing internment in the South since then.

In 1958 MacBride was briefed by the then Greek government to fight the deportation to the Seychelles and detention there by the British of Archbishop Makarios, the Cypriot nationalist leader. He demolished the British case by demonstrating that no state of emergency existed in the Seychelles and forced the release of Makarios, with whom he then became quite friendly.

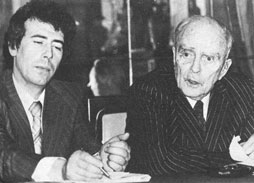

Not long after that he went to South Africa where he was welcomed by the government because of his father's role in the Boers' struggle against the British. The South Africans were very embarrassed when he raised the question of political prisoners and they actually released some prisoners. MacBride was struck by the effect outside pressure could have on even a regime like the South African one and in 1961 he and Peter Benenson, a British lawyer, founded Amnesty International to campaign for prisoners of con. science all over the world. Amnesty worked, not by mass agitation, but by the careful collecting of information and lobbying, much of it unpublicised. Here MacBride's legal, diplomatic and negotiating skills and experience really came into their own and Amnesty soon established itself as the leading body opposing arbitrary arrest, imprisonment and torture.

Many prisoners in dozens of countries owed their release or improvements in their conditions to its work. MacBride was chairman of Amnesty's international executive from 1961 to 1974 and is still chairman of its Irish section. In 1963 he was appointed full-time secretary general or the Geneva-based International Commission of Jurists (ICl), an association of lawyers interested in international protection of human rights, a post he held until 1971. The Cold War era was not quite over at the time he was appointed and the ICJ was seen at the time as a pro-Western group, more interested in abuses of human rights in Eastern Europe than in countries friendly to the US. Indeed it later emerged that some of its funds had come from the CIA.

MacBride worked to give both it and Amnesty a more independent position, critical of abuses both West and East. This brought him into some conflict with US officials who had been only too pleased in 1963, when the lCJ had criticised the Chinese occupation of Tibet. In 1965 Averell Harriman, President Johnson's special envoy, whom MacBride had got to know when he was a Marshall Aid administrator, invited him to Washington to talk about the Vietnam War to a private meeting of senior officials, including the Secretary of State and the Secretary for Defence. There was consternation when he denounced the US born bing of Vietnam. In 1969 MacBride wen t to North Vietnam and was horrified at the destruction of civilian targets and the US use of anti-personnel weapons. He has kept a fragment of an anti-personnel bomb, meticulously stamped with its US manufacturers name and address.

He went to many countries in connection with human rights investigations, but perhaps his most bizarre experience was in Teheran where he in terviewed the Shah's Prime Minister. He admitted quite readily that his regime practiced torture but was at pains to stress that they used only the most modern scientific techniques, under the guidance of US and British advisers. When MacBride got the officially approved text of the interview he was amazed to find that the admission of the use of torture had not been deleted. The only change was that the US and British advisers were now referred to simply as "foreign". He was not surprised when the Shah's regime was overthrown and, though he deplores the brutality of Ayatollah Khomeini's regime, he sees it as largely a product of the Shah's government which was supported for so long by the West.

In 1973, because of his record of work for human rights and especially against colonialism and apartheid, the African states nominated him as the first United Nation's Commissioner for Namibia (South West Africa) with the rank of Assistant Secretary General of the UN. His task was to mobilise international opinion against South African rule there and over the next three years he helped to put that little-known country on the map though the South Africans are still stubbornly refusing to get out. In 1974 Sean MacBride received the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his work for human rights and in 1977 he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize by the Soviet govern· ment, becoming the first person ever to hold both awards. In the following year he became the first non-US citizen to be awarded the American Medal for Justice.

In 1973, because of his record of work for human rights and especially against colonialism and apartheid, the African states nominated him as the first United Nation's Commissioner for Namibia (South West Africa) with the rank of Assistant Secretary General of the UN. His task was to mobilise international opinion against South African rule there and over the next three years he helped to put that little-known country on the map though the South Africans are still stubbornly refusing to get out. In 1974 Sean MacBride received the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his work for human rights and in 1977 he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize by the Soviet govern· ment, becoming the first person ever to hold both awards. In the following year he became the first non-US citizen to be awarded the American Medal for Justice.

In the meantime in 1976, after 50 years of marriage, his wife, Kid, died. Sean MacBride was now 74 and had received three of the world's most prestigious awards. For most people it would have been time to retire from public life and take things easy.

MacBride did nothing of the kind. He had become increasingly concerned about the nuclear arms race and in recent years he has devoted himself, with all his extraordinary energy, to campaigning for nuclear disarmament as President of the Geneva-based International Peace Bureau. He has trenchantly denounced the alliance of big business and financial interests in the US which fosters the development of ever more powerful and horrific weapons. This made him quite popular with the Soviet leadership until he denounced, just as strongly, the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and martial law in Poland. Disarmament has been his main preoccupation over the last five years but he has also found the time to chair a major UNESCO commission on international communications problems whose report, in 1980, aroused a storm of opposition in the Western press because of its sharp attack on the Western news agencies' reporting of Third World issues. He is currently chairing an international commission on the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the massacres in the Palestinian refugee camps.

At home he has taken no part in party politics since the 1960s but he is President of Irish CND and Vice chairman of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties. During 1979-80 he acted as co-chairman of a committee which strongly condemned the harsh and antiquated Irish prison system. And he is an outspoken opponent of any attempt to compromise the Republic's neutrality or involve it in any common EEC defence or security policy. He remains strongly opposed to partition, arguing that it was imposed and is maintained against the will of the majority of Irish people, that over 60 years it has cost thousands of lives, has led to the jailing of tens of thousands of men and women, and has resulted in coercion and repression on both sides of the border. He is opposed to the military campaign by the IRA and INLA, not because he is a pacifist - he isn't - but because he believes there is still scope for political resistance to injustice in the North. However he argues that the only way to end violence in the North is to remove its cause - partition. As he said in his speech accepting the Nobel Prize in 1974: "If those vested with authority and power practice injustice, resort to torture and killing, is it not inevitable that those who are victims will react with similar methods?"

Sean MacBride has had a long and remarkable career: guerrilla fighter, brilliant barrister, politician and diplomat, human rights advocate, peace campaigner. It has often been controversial. Some of his actions over the years, notably during the Mother and Child crisis, aroused fierce criticism, even from his republican and radical colleagues. Some of them argued that he was treading the same path as the reformed revolutionaries of Fianna Fail. But in recent years Sean MacBride's name has again been identified with radical causes at home and abroad. And throughout his long career certain objectives have remained constant: the defence of political prisoners and human rights, self-determination for colonial countries, Irish unity, and, latterly, disarmament.

As he begins his 80th year he is still pursuing those objectives with an energy and determination that would be remarkable in someone half his age.

Notes

There were a few minor inaccuracies in the first article on Sean MacBride. In 1921 he became OC of the Active Service Unit of B Company of the Third Battalion of the Dublin IRA, not OC of the Company. He was travelling to the Continent, not returning from it, on the day Kevin O'Higgins was shot in 1927. The international anti-imperialist conference he attended in 1929 was in Frankfurt, not in Berlin. He left the IRA in 1937 not early in 1938. In the MacCurtain case in 1940 it was the Supreme Court that the authorities were unable to summon in time to hear a habeas corpus application, with the result that MacCurtain 's execution had to be postponed. For information on the early years of Clann na Poblachta, dealt with in this article, I am grateful to Gerard O'Sullivan who allowed me to read his dissertation, "Clann na Poblachta 1946-51 ", submitted for the BA in European Studies at the NIHE, Limerick, in 1978. For access to the Cabinet papers of the first Inter-Party government I am grateful to Mr. Breandan MacGiolla Choille, Keeper of the State Papers.