The Way Nowhere

The Government's economic plan, "The Way Forward" makes assumptions about output and export growth, which are entirely unrealistic. It avoids almost all the difficult political decisions on economic management including how the budget deficit is going to be reduced drastically next year and it neglects consideration of basic issues related to the economy.

The acknowledgement of the serious mess of the economic crisis is welcome as are the tentative indications that hard decisions are being contemplated, particularly in relation to the ESB and CIE, but as a blueprint for economic recovery it is gravely deficient.Indeed the symptoms of the malaise which have caused our debilitation in large measure, notably the avoidance of hard decisions, are all too prevalent throughout the entire document.

The acknowledgement of the serious mess of the economic crisis is welcome as are the tentative indications that hard decisions are being contemplated, particularly in relation to the ESB and CIE, but as a blueprint for economic recovery it is gravely deficient.Indeed the symptoms of the malaise which have caused our debilitation in large measure, notably the avoidance of hard decisions, are all too prevalent throughout the entire document.

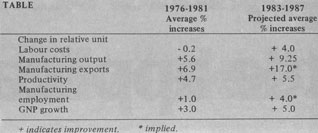

The central feature of the plan is the envisaged growth in output in the manufacturing sector. This growth is the main source of the planned average GDP growth of 5% and export growth of l2 1/4%. A sustained improvement in wage-eost competitiveness is assumed of 4% per annum giving rise to annual increases in industrial output of 9 1/4% and industrial exports of 16%-17% approx. Manufacturing employment is expected to increase by 9,500 after allowing for 5 1/2% per annum productivity growth.

This hypothesised performance of the manufacturing sector appears totally unrealistic compared to the performance in the 70s let alone when the greatly less favourable environment of the 80s is considered, both intemational and domestic. The accompanying table shows the performance of the various economic indicators in the 70s. It is extremely unlikely that the wage-eost competitiveness gains can be achieved. Firstly the assumed average increase in foreign unit labour costs is too high at 7.5% per annum. Secondly, those in manufacturing employment, particularly those with secure jobs in rapidly growing companies, will not accept real income declines for the next few years.

Even if the wage-cost competitiveness gains were achieved, manufacturing industry would still not perform as expected. In the 70s growth in manufacturing output and exports was principally due to the growth in new foreign-owned industry especially the electronics and chemicals sectors. Much of this growth itself was due to new plants starting up rather than expansion of existing industries. The relationship between industrial growth and unit labour costs was tenuous to say the least. Output growth was more or less matched by productivity growth yielding a negligible increase in manufacturing employment.

The growth industries in Ireland in the 80s will again be what Telesis calls "complex-factor-cost industries". If wage-eost competitiveness deteriorates it may prove a major hindrance to growth, but improvements in it will not be the engine of growth in these industries, no more than it was in the 70s. In this Ireland is very much a developed world economy, where, in the 80s, growth in industrial output will be to a considerable extent determined by productivity growth. Output growth will be matched by productivity growth and industrial employment will not increase. Ireland did not deviate very much from this pattern in the 70s and is even less likely to in the 80s.

There are many interesting analyses in the plan for instance: the section on Energy. Detailed forecasts are made for primary and final energy demand. It is evident that a coherent energy policy is being developed for Ireland for the first time. Unfortunately this section is marred by an all too prevalent feature of the plan - the avoidance of harsh or controversial decisions. In this case the White gate oil refinery issue is glossed over. So also is ESB costs and pricing policy, despite the fact that our electricity prices are now the highest in Europe.

Avoidance of any harsh decisions becomes even more serious in the area of budgetary policy, despite the fact that the budget deficit is more out of control than it ever was. Previously excessive growth in expenditure was the problem, in 1982 the shortfall in revenue due to the severe recession has made the problem even more intractable. The plan's target for the current budget deficit in 1983 is about £750m, yet the predicted opening deficit is at least £1,350m, assuming the implementation of an unpopularly low 5% increase in public sector pay and 10% increase in social welfare rates.

If income tax and indirect taxes remain the same in real terms, with PRSI extended to civil servants and higher incomes then the burden of adjustment of the current deficit (approximately £350m) falls on enormous "bouyancy" and large public expenditure cuts. No details are given of these cuts in the plan. Neither is there any contingency set out if the unrealistically high GDP growth and resultant revenue "bouyancy" fail to materialise.

Despite the critical nature of Ireland's structural economic problems like the budget deficit and especially unemployment, the plan does not adequately take stock of fundamental economic policies in Ireland. It merely recommends more of the same with a dollop of income restraint thrown in. There is a clear case for a reappraisal of industrial policy. Such sacrosanct pillars of policy as the present grant schemes and the Manufacturing Corporation Tax of 10% may not be the best way to maximise. industry's contribution to the economy‡ in the 80s.

The present manner of enforcement of tax laws especially for the self-employed seems‡ ludicrous in an economy collapsing under the weight of its budget deficit. Likewise wealth and resource taxes should be seriously considered, rather than dismissed without a fair trial. If manufacturing employment does not increase the impossible burden of curbing the rise in unemployment will fall on the private services sector. This‡ sector cannot possibly achieve the task in the present environment. One alternative is to propose the economic heresy that public sector employment should be increased on a planned basis.

There does not seem any realistic hope of solving the unemployment problem in the context of present economic constraints with current policies and conventional full-time jobs. It is no solution to propose that planned pie in the sky must materialise because it is the only apparent answer to the inexorable rise in unemployment. Neither is it much use to dwell entirely on reforming the budget deficit if the most critical economic problem (unemployment) is ignored.

The reality must be faced. The politicians must honestly tell us what they propose to do to govern a society with unemployment rates of 20% and 30%. Otherwise they must propose how they see chronic unemployment being alleviated. Obvious practical solutions include mandatory early retirement schemes, job-sharing and more part-time employment. Serious consideration of one of these measures would necessitate government action of some sort. For instance reform of procedures for PAYE and social welfare would be necessary for part-time employment to be a realistic option.

Many serious economic issues must be faced now. Neither proposing pie in the sky nor removing Charlie Haughey from office. will suffice as a solution to Ireland's economic problems.