Have SPUC, Will Travel

Colm Toibin got on the anti-abortion bandwagon and travelled with it to its candle-lit march.

Father Nolan was saying ten o'clock Mass on Christmas morning in Enniscorthy Cathedral. Father Nolan had an announcement to make. He told his congregation that a bus would be leaving from the Abbey Square at a quarter past twelve on Monday morning. Its destination was Dublin and a march for the rights of the unborn child. The interest in the bus was disappointing so far, Father Nolan said. He would like parents to consider it as a day out for themselves. He would like parents to consider bringing their children on the march.

Father Nolan was saying ten o'clock Mass on Christmas morning in Enniscorthy Cathedral. Father Nolan had an announcement to make. He told his congregation that a bus would be leaving from the Abbey Square at a quarter past twelve on Monday morning. Its destination was Dublin and a march for the rights of the unborn child. The interest in the bus was disappointing so far, Father Nolan said. He would like parents to consider it as a day out for themselves. He would like parents to consider bringing their children on the march.

It was Monday December 27 and there was no way of getting out of Enniscorthy. The trains weren't running, nor were the buses. CIE was staying at home that day. Thus was Father Nolan's bus a godsend. Father Nolan was my shepherd. Father Nolan was a true friend to those in need of getting back to Dublin on December 27. But Father Nolan's bus, hereafter called the SPUC bus, had other distinct advantages. One, it wouldn't be stopping in every god-forsaken village along the way. Two, it was cheap. The train costs £12. The bus £6.80. But the SPUC bus was just what this reporter needed. The SPUC bus cost £2. And that would take you all the way up and back. Travel SPUC. SPUC saves you time. SPUC saves you money. Every town should have one. See Ireland with SPUC. Three cheers for SPUC. There was a moral in this story.

The first thing I saw in the Abbey Square in Enniscorthy on Monday December 27 at a quarter past twelve was a Knight of Columbanus, a common enough breed about the town. The second thing I beheld was a Fianna Fail councillor, also common in their own way. There were two young blokes leaning against a monument to Thomas Rafter and there were about twenty women from the town. "We should have brought a pack of cards," said one. "I don't want to see another card until next Christmas," replied another. There was a priest, there were a few school girls. There were some little children. And a woman who as long as I remember has never been able to keep her nose out of the whole town's business. These were my fellow travellers. And then there' were some late-comers. One of them was wondering how everyone got over the Christmas.

The bus arrived in the square and we got on. There were still some empty seats. The Knight of Columbanus, apparently, had merely come to offer the blessing of his august organisation to the bus and all its passengers. He did not get on the bus, and as it moved away he could be seen walking up Castle Hill.

The bloke who sat beside me looked about thirty. He was a farmer. He hadn't been in the movement long, just about six months, and he hadn't had time to be very active in it. Why did he join? He thought for a moment and told me that his wife had had a miscarriage and he had realised that what she was carrying was a human being. He thought this amendment was 'going ‡to work. It was a rough world, he said, and he was glad something good was going to happen. But the miscarriage wasn't the only reason he joined. There were other reasons. He supposed I had my reasons as well. He glanced at me. I could hardly tell him that I was only here for the bus. I looked out the window.

We stopped in Ferns and more SPUC people got on. One woman sat in front of me beside the Fianna Fail councillor. They talked the rest of the way to Dublin. All their colleagues in SPUC also talked the rest of the way to Dublin. People like this reporter who had never been on a SPUC bus before may imagine that they.say the Rosary, sing hymns or listen to sermons on SPUC buses. This is not the case. This SPUC bus was a day out, as Father Nolan had promised, and the SPUC people blathered away to each other as though it was a day trip to Curracloe. The Fianna Fail councillor and the woman from Ferns, for example, got into a long discussion about women's lib and its ins and outs. "Women don't 'go for the sort of man who carries the shopping bag," said the councillor. The bloke beside me talked to another farmer about cows and fields and how to kill badgers. "Hit him on the nose with a bar," was one suggestion.

"God, I didn't feel the journey," said the woman as the SPUC bus stopped in 0 'Connell Street. Everybody took out flasks of tea or coffee and everybody unwrapped sandwiches. There was going to be a sort of picnic on the SPUC bus. And then the passengers were going to join the march with other SPUC people. But there was no hurry. There was time enough.

The SPUC march was smaller than the anti-amendment march just one month before. There were no nuns on the anti-amendment march, but this march was creeping with nuns of every description. There was one TD on the anti-amendment march. (The people of Limerick have since seen to that.) Jim Tunny, Sean Barrett and Alice Glenn were on this march.

Then there was the woman the other marchers didn't want to go on the march. She was dressed all in black and had a big banner over her head. The banner proclaimed: 'Abortion is Mortal Sin'. There was a photograph of Pope Paul VI on one side of the banner. She had been asked by the organisers and a Capuchin priest not to go on the march. She might put others off, and the movement was non-sectarian. She talked about the devil. "The devil is making hooks in the eyes of the world." She talked about the Pope. " 'Young people of Ireland, I love you,' he said. Well, if he saw what I saw them doing last Saturday night he wouldn't say that." She went on more about the Pope. "I wouldn't thank him if he flew in this morning and out tonight. Where are the bishops? Why aren't they here? They should be leading the march. Abortion is the work of Satan."

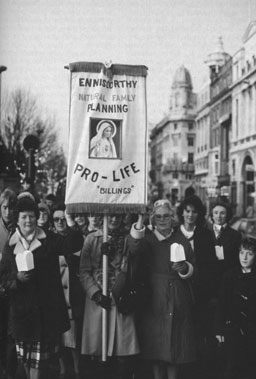

She was following the march up Kildare Street where two children had left a wreath at the gates of Leinster House. She was following the nuns and the priests and fathers and mothers who had lit torches for SPUC and were going to carry them all the way down Grafton Street to the Central Bank. She was following the children who had been brought out for the day. One of the children, whose friends were probably at home watching Bosco, held a banner which declared "RTE: Regularly Touting Evil". The Enniscorthy branch of SPUC had the best banner. The woman in black, whom these people didn't want on their march, was born near there.

Then came the moment which Loretto Browne, the high priestess of SPUC, had been waiting for. A lorry was parked on Dame Street in front of the Central Bank and Loretto could address the crowd once Alice Glenn had finished. As the buses roared by Loretto told the SPUC people that politicians who said one thing in public and another in private should look out. Hell hath no fury like Loretto Browne.

The march was over. SPUC moved away in peace. The Knight of Columbanus would be waiting in Enniscorthy for his family to come home. It had been a great day for SPUC. A Capuchin monk began to walk alongside. "Did you try and stop a woman dressed in black going on the march?" I asked him. He laughed. "I asked her not to march," he said. "If the media saw her, they'd make a haymes of it."