The Chickens Come Home to Roost

Those who waited for ten years for the new beginning with Charlie Haughey, must have begun to wonder by now what the long wait was all about. In the seven months since he has become Taoiseach, Charles Haughey has failed to make any significant impact, on any of the issues on which he was most looked to for leadership and change: the economy, the North and security. But worse than that, he has revealed himself as a weak leader who mistakes public relations gimmicks, for decisiveness and courage.

By far the worst and most alarming indication of his weakness and vacillation, was the Donlon affair. For reasons which were perfectly valid and had nothing to do with pressure from Neil Blaney, Haughey wanted Sean Donlon out of the sensitive post of Ambassador to the United States. Haughey believed that Donlon had exceeded his brief in his exertions against the Irish National Caucus and that it was no part of the duties of an Irish diplomat to be frustrating the efforts of American Congressmen, to enquire into the iniquities of the British administration in Northern Ireland.

By far the worst and most alarming indication of his weakness and vacillation, was the Donlon affair. For reasons which were perfectly valid and had nothing to do with pressure from Neil Blaney, Haughey wanted Sean Donlon out of the sensitive post of Ambassador to the United States. Haughey believed that Donlon had exceeded his brief in his exertions against the Irish National Caucus and that it was no part of the duties of an Irish diplomat to be frustrating the efforts of American Congressmen, to enquire into the iniquities of the British administration in Northern Ireland.

Haughey also was deeply sceptical of the advice being given by the establishment within the Department of Foreign Affairs, on the Northern Ireland issue. It was these officials who were, if not the architects, then the engineers of the consensus line on Northern Ireland, which Haughey privately ridiculed for years. (The consensus line being that the there could be constitutional change Northern Ireland, only with the consent of the majority there; Haughey's being that this avoided the issue, in that it legitimised the artificiality of the Northern majority and effectively ensured that there could never be substantial progress on the issue).

Donlon was very much part of this establishment. He had been the official in charge of the Northern Ireland division of the Anglo-Irish section of the Department of Foreign Affairs, for most of the 1970s. In this capacity, he was very much more visible as a public servant than most of his colleagues. He socialised with the gregarious SDLP leaders and with the establishment journalists in the South, and also developed close personal contacts with the Lynch faction in Fianna Fail and the Garret Fitzgerald faction in Fine Gael. Inevitably he was associated with those people in Irish politics, who were identified - correctly- by Haughey, as his political enemies. Hence Haughey's determination to shift Donlon, was doubly motivated.

Of course what he should, as a consequence have done, was to move Donlon to a post which was clearly junior - e.g. Ambassador to Canada or Australia - and then defend his decision to all comers. This would first of all have let the civil service establishment, know that he was intent on bending it to his own will, as it is his democratic right to do.

It would also have clearly indicated his displeasure with a form of diplomatic activity of which he disapproved - this is not to say that Donlon acted improperly at any stage, only that Haughey clearly disapproved of his record in Washington. It would also have had the benefit of disassociating him from the consensus line on Northern Ireland, which was personified by Donlon.

Instead Haughey sought to deprive the moving of Donlon from Washington of any real significance, by the pretence that it was not really a demotion, that it had no political overtones and that nothing essentially had changed. This was achieved by the decision to move Donlon to the UN post and it classically pin-points Haughey's essential political weakness. He basically doesn't have sufficient self-confidence in his own judgements and political views to show them openly and courageously and then defend them vigorously.

It would have been bad enough to have shifted Donlon out of Washington in a manner that suggested that there was no significance attached to it, but the situation was made immeasurably worse by backing off the decision once the political flack started to fly within the Department of Foreign Affairs itself, the political establishment represented by Jack Lynch and Garret Fitzgerald, and within his own cabinet.

And then a flat lie was issued, denying that there was any foundation whatsoever to the reports that Donlon was to be moved. And, to cover it all, Haughey was cornered by Garret Fitzgerald, into repudiating the Irish National Caucus, to which Haughey was vaguely sympathetic.

All in all, it represented the most pathetic collapse of leadership that has occurred within living memory. Although Jack Lynch was vacillating and indecisive at times, he was never quite this bad. Liam Cosgrave may not have been much of a Taoiseach, but whatever else he was, he was his own man. And, of course, something like this would have been unthinkable with either Sean Lemass or Eamon de Valera. It was little wonder that Kevin Boland should dispute that Charlie Haughey was leading Fianna Fail. "It's not clear whether it's George Colley, or a faction of his within the cabinet, or whether it's Garret Fitzgerald that's leading Fianna Fail, but it's not Charlie Haughey," said Boland last month.

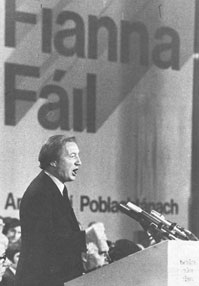

On Northern policy, Haughey has also demonstrated a lack of courage in stating his convictions. In his Ard Fheis speech, he came near to stating what his true position is: that there must be progress towards a united Ireland with or without, the agreement of the majority in Northern Ireland. However he backed off this by repeating the shibboleth about agreement, which of course negates everything said otherwise.

Then at his meeting with Mrs. Thatcher in May, it was clear that he didn't either reiterate Fianna Fail's 1975 policy statement on the North, which calls for a commitment by the British to disengage from Northern Ireland, or give his own more positive view: that the British should push towards Irish unity in spite of the opposition of the Northern majority.

Essentially Haughey's current stance on the Northern question is no more than a pale and confused reflection, of what Jack Lynch stood for and what Garret Fitzgerald postulates. Those who were enthusiastic about his becoming leader had very different expectations.

On security, it was also expected that Haughey would be somewhat different. He was privately caustic about the bombast and rhetoric that accompanied the succession of outrages we have had here, both North and South, in the last decade. Haughey was known to agree with the thesis that all these security measures and obsessions were to no avail, while the basic political problem went unresolved. Indeed that the rhetoric made matters even worse in that they raised expectations that something could be done, while the political problem remained ignored. It was also thought that he would stop the undermining of our judicial procedures and civil rights here, in response to the emotions of the latest outrage. But what has happened?

Within days of his becoming Taoiseach he issued a loud rhetorical statement on the killing of members of the Northern security forces near the border. He did it primarily, one presumes, to demonstrate that he was as opposed to violence as the next and that he would not prove soft on the security issue.

One might have allowed him one or two such statements to protect his flank, but the problem is that once one starts down that road; it is difficult to know where to stop. Inevitably we have gone further down that road and with the murder of the two Gardaí in Roscommon last month, we have gone even further. Again there have been promises of new security packages, with open hints that these would cut in further in to the area of civil liberties and not a mention of the basic reason why these outrages occurred in the first place. And when it emerges that most of the high profiled security operation in South Galway last month was primarily a cosmetic exercise, it will be appreciated that very little has changed since the Paddy Cooney era.

The handling of the economy has been no more assured under Charles Haughey than it was under Jack Lynch, who was never suspected of having any great expertise in that area. The inflation rate has been fuelled by the budgetary increases, unemployment has soared again over the 100,000 mark, the growth rate has stagnated and our borrowing rate has remained at a level which, there is general agreement, is unsustainable. Meanwhile, there have been no new plans for economic regeneration, no inkling of a new approach which would rescue us from the depths of recession. Perhaps too much was expected of Haughey in this area but, in the absence of such expectations, what was there to expect of him?

So what has been the point of having Haughey as Taoiseach at all? Nothing seems to have changed on Northern policy, on the economy, or on security. He was the great white hope of the dissidents, not just those within Fianna Fail, but those who were dismayed generally by the futility of the consensus line on Northern Ireland and the vacuity, at best, and harmfulness at worst, of the security obsessions.

Haughey carried a lot of baggage with him into the leadership of Fianna Fail and those who supported him, hoped that the baggage would not prove too burdensome and would be lightened by the stimulus he would give in the economic, security and Northern areas of policy. But this has not happened. Instead, the baggage has begun to prove very burdensome indeed.

The Magill revelations on the arms crisis should never have proved a major problem for Haughey, but now they have for two main reasons. The first is that things were going so badly for him in other spheres that he couldn't ride through the Magill revelations, in spite of the triumphal welcome of Ray McSharry at Dublin airport on the day that the first issue was published - and indeed it wasn't because of the amenability of an otherwise hostile press, that this ploy didn't work.

The second reason they have proved a problem is because of his own refusal to speak out on the issue in a frank and truthful manner. True, he would have difficulties in explaining his denials during the course of the arms trial and at the Committee of Public Accounts, but he is going to have to face the truth at some point, and the earlier the better.

The fact is that Haughey has believed since the conclusion of the arms trial that the issue was settled once and for all and he has refused to allow his mind to dwell on the subject. But this evasion is now no longer possible.

The significance of Jim Gibbons' challenge is that it was revealed for the first time that, Haughey promised he would clear Gibbons' name by stating that his (the latter's) evidence at the arms trial was true and, by implication, that his own was not. Haughey can now either ignore his challenge, in which case he will have lost his authority over the party in the same manner as Jack Lynch did when Jim Gibbons refused to vote for the Family Planning Bill. Or Haughey can take Gibbons on 'within the Parliamentary

The significance of Jim Gibbons' challenge is that it was revealed for the first time that, Haughey promised he would clear Gibbons' name by stating that his (the latter's) evidence at the arms trial was true and, by implication, that his own was not. Haughey can now either ignore his challenge, in which case he will have lost his authority over the party in the same manner as Jack Lynch did when Jim Gibbons refused to vote for the Family Planning Bill. Or Haughey can take Gibbons on 'within the Parliamentary

Party, in which case he will have to deal 'with the substance of the arms crisis affair and risk drawing Jack Lynch and Des O'Malley into the controversy against him.

Then, of course, he must face the challenge of the Dáil debate in October. Either he refuses to be drawn on the issue then, in which case all kinds of inferences will be made about the significance of his silence, or he replies, in which case either he admits to having not told the truth, or he worsens the situation still further for himself, by further untruths or evasions.

But the greatest difficulty arises for him in his handling of future press conferences and radio and television interviews. One of the effects of the Magill articles has been to inform journalists about the salient facts of the 1970 arms crisis and therefore questions about this affair are going to be more informed and perceptive, than they might otherwise have been.

Either Mr. Haughey refuses to give such interviews, which refusal will greatly restrict his access to the public and raise doubts about his suitability for office, or again he will be forced into evasions or admitting that he didn't tell the truth at the arms trial. Every time this occurs, there will be further controversy about the arms crisis, giving rise to further questions at press conferences and interviews.

This is now a matter of considerable seriousness for Mr. Haughey, even though its full significance may not be appreciated as yet. Unless he tackles the issue head on and truthfully, he runs the risk of it corroding his position electorally and inside his own party and cabinet. It could lead to a situation in which the question would be not whether he would win the next election but whether he would stay until the next election. It may be invidious for Magill to be making this point, but the situation arises not so much out of what was revealed here, but of the adverse external circumstances and Mr. Haughey's own introverted reaction to the affair.

His position within his own party is another major problem for Haughey and again was part of the baggage he brought with him to office. He is a highly contentious figure within Fianna Fail, but it was hoped that he would restore even the gloss of unity once elected. Instead the position has worsened. It wasn't helped of course by Jack Lynch's statement about Martin O Donoghue or by George Colley's denying he had promised loyalty, but the rest has been largely Haughey's own doing.

His cabinet appointments reflected neither the new approach he was expected to bring to Government, nor the need to unify the party, let alone make the best of the available talent. Michael O'Kennedy's appointment to Finance, prompted by gratitude for his support in the leadership election and a desire to have his own tame nominee in a sensitive post, was a mistake and again reflected Haughey's lack of self-confidence. If he was sufficiently assured in his own economic policy objectives, it would not have mattered whether the person appointed to Finance had opposed him in the leadership election. There were good reasons - mainly cosmetic - for moving George Colley from that position, but surely somebody of the calibre of Des O'Malley or Martin O'Donoghue, could have been drafted in?

Des O'Malley is admittedly a very unpleasant individual. His role in the arms crisis was one which Haughey has good reasons to feel resentful about - the full story of that role and, especially, of the nature of surveillance under which Haughey was placed, has not yet been revealed and O'Malley is unaware that Haughey knows the full story. But the fact is that, in spite of O'Malley's behaviour then, he is still a fit person to be in Government and he has the ability to meet the challenges of a senior position like Finance.

It is true that Haughey is highly suspicious of O'Malley's judgement - and again with good reason - but if Haughey had sufficient self-confidence in his own abilities, this would not have been a major problem. There might also have been difficulties in negotiating a new National Understanding, given O'Malley's personality, but again, Haughey himself could have counteracted these deficiencies, or even appointed another, such as Martin O'Donoghue, to take responsibility for that.

The management of the economy has a lot to do with the personality and projection of the Ministers in key positions in Government. O 'Kennedy simply lacks credibility in Finance. O'Malley would not.

It is true that McSharry, Reynolds and Woods, were considerable additions to the cabinet, but the effect of these appointments were off-set in the first place, by the dropping of Martin O'Donoghue and then by tile appointment of Ministers for State whose suitability for Government office was not immediately apparent. At least two of these have entirely failed to meet the demands of office, although three of Haughey's most, fervent supporters, Killalea, Fahey and Doherty, are considerably more able than they are given credit for.

Haughey committed a major blunder on the day before he was elected Taoiseach by allowing George Colley dictate who should be Ministers for Justice and Defence and generally hold a veto over the structure of Government. It was for this reason that Gerry Collins was retained in Justice - this represented a very significant compromise by Haughey - and that Padraigh Faulkner was kept in the cabinet.

Haughey's stature within the party would have been immeasurably improved, had he shown himself to be his own man from the outset. Had he appointed what he considered to be the best cabinet and had he challenged the George Colley threat from the beginning - first by telling him where to go on Monday, December 6, when he laid down the terms of his remaining in Government, and then when he denied the promise of loyalty. Then Haughey's stature within the party would not be in doubt. But again he lacked the self-confidence to do this.

Fianna Fail is now hopelessly divided. Charlie Haughey will understand to what extent when he learns that two of his ministers, George Colley and Des O'Malley, are saying the same things about him in private that he said about Jack Lynch when the latter was Taoiseach. A significant proportion of the backbench TDs who voted against him last December have not been won over and a number of those who enthusiastically supported him are having doubts. Haughey himself has almost entirely isolated the party secretary, Seamus Brennan, who was prepared to forget his past misgivings about Haughey and buckle under in preparation for the next election. The party organisation is now being run by Haughey's own henchmen and in a manner which has alienated the corps which brilliantly organised the last campaign.

All is not lost as yet, but time is running out for him. It has been one of Haughey's political maxims that elections are not won in the run up to the polling day but in what determines the mood of the electorate some six months to a year before the election takes place. It is apparent from directives he has recently issued to various Government Departments, concerning the need to have legislation on the statute books by a year's time, that he is not contemplating an election within twelve months, Indeed the indications are that he will wait until 1982 before calling one, although this could all change were there to be highly favourable results in the two forthcoming by-elections,

Given this, it is clear that the Government fortunes will have had to change considerably for the better by the first half of next year. It is by no means impossible for this to occur.

First he has the opportunity of a cabinet reshuffle when the EEC Commissioner is appointed later this year. The opportunity is extended if he opts to propose Padraigh Faulkner as Ceann Comhairle, and given the arithmetic of the Louth constituency, this makes a lot of sense. There are suggestions that he would move Brian Lenihan to Finance, in which case Haughey can start making his retirement plans, However if he moves O'Malley in there, it will serve as an indication that he is serious about economic policy and that he is doing something decisive to heal the rift within the party.

There are several indications that he will drop Gerry Collins, in which case he leaves the way open to appoint someone whose image on the civil liberties and security front, would be more sympathetic and who might push rapidly ahead with the law reform. It seems likely he will opt to move Sean Doherty into the full cabinet post.

Albert Reynolds should have made some discernable progress with the telephones by about a year's time and his plans for Dublin transport should be bearing fruit about then too. There is the vague hope of an oil find which would engender confidence and with a reasonable National Understanding successfully negotiated, then the picture may not be quite that gloomy.

But Haughey is going to have to start delivering on the expectations which his election as Taoiseach aroused. He needs to show his mettle on the three critical areas of Government: the economy, the North and security. Without the self-confident assertion of his own personality in these areas, his liabilities may prove too great a handicap.