Shaking more than barley

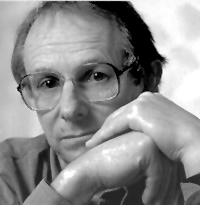

Ken Loach doesn't make films for Hollywood. He makes controversial films which challenge the status quo. In his 70th year, he has been rewarded by a Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival for his latest film on the Irish civil war. By Declan Burke.

'It's typical," Ken Loach said to a journalist during a visit to the Bandon set of his latest film, The Wind that Shakes the Barley, "you managed to be here this morning for the only scene in which the word 'socialism' is used."

The word may only be used once in the film, but the underlying theme of The Wind that Shakes the Barley, as is the case with most of Loach's output, is the pointing up of social injustice. In this case, the solidarity of the rank-and-file of a Cork Flying Column fighting the occupying British forces during the War of Independence is shattered when the treaty with Britain is signed; while some believe peace is worth the price of compromise, others believe they've been hoodwinked into fighting and dying in order to perpetuate the same system under a different flag. In the civil war that follows, brothers Damien (Cillian Murphy) and Teddy (Padraic Delaney) fight on opposite sides, the former resolutely idealistic, the latter a lethal pragmatist. The ending – gritty, downbeat, unsentimental – isn't so much predictable as inevitable, but it's no less shocking for all that. Ironically, for a man who has made a career out of eschewing the easy option of 'Hollywood endings', the 69-year-old director was this week presented with a Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival that appears to have come straight from the drawer labelled 'deus ex machina'.

Born in Nuneaton, England, in 1936, Ken Loach's earliest years were spent moving around the North of England as his family relocated time and again due to second world war. Having served two years of National Service with the RAF, Loach read law at Oxford, there immersing himself in the drama group at St Peter's Hall; on leaving university, he worked for a time as an actor in repertory theatre. In 1963, he joined the BBC as a trainee television director, and was soon directing episodes of Z Cars. His first major undertaking was directing Catherine, starring Tony Garnett, but his breakthrough came in 1966 when he wrote and directed the teleplay Cathy Come Home, a cinema vérité-style documentary tale about teenage homelessness that caused something of a political furore and the subsequent setting up of the charity Shelter, although Loach himself refuses to take any credit for this.

Born in Nuneaton, England, in 1936, Ken Loach's earliest years were spent moving around the North of England as his family relocated time and again due to second world war. Having served two years of National Service with the RAF, Loach read law at Oxford, there immersing himself in the drama group at St Peter's Hall; on leaving university, he worked for a time as an actor in repertory theatre. In 1963, he joined the BBC as a trainee television director, and was soon directing episodes of Z Cars. His first major undertaking was directing Catherine, starring Tony Garnett, but his breakthrough came in 1966 when he wrote and directed the teleplay Cathy Come Home, a cinema vérité-style documentary tale about teenage homelessness that caused something of a political furore and the subsequent setting up of the charity Shelter, although Loach himself refuses to take any credit for this.

His feature-length debut, Poor Cow (1967), highlighted his 'cinematic immaturity', according to Loach, but Kes (1969), a hardhitting drama about a young boy's relationship with a kestrel, set in Northern England against a backdrop of crippling poverty, set the tone for his future work. A huge success at the box-office, the film ironically heralded a decade in which Loach found it increasingly difficult to get his films into theatres (most noticeably Family Life (1971), and Days of Hope (1975), an extended documentary about the British Labour Party) – his vision of 'social-conscience realism' was out of step with the rise of Margaret Thatcher's Conservatives. A Question of Leadership (1983), a four-part documentary on Thatcher's Britain commissioned by ITV's South Bank Show, was spiked by then editor Melvyn Bragg.

After a lean period in which he was unable to secure financing for any projects, Loach directed the feature-length Fatherland (1986), his first time to work in conjunction with the new Film Four. He followed this in 1990 with a typically robust examination of British policy in Northern Ireland, Hidden Agenda, which Conservative MP Ivor Stanbrook less-than-graciously described as Cannes' "official IRA entry" (it won the Jury Prize that year). Its critical acclaim and box-office success rehabilitated Loach, although it's doubtful he will ever feel comfortable in the mainstream: turning down an OBE in the '70s, the erstwhile Oxford law student claimed, "It's not a club you want to join when you look at the villains who've got it. It's all the things I think are despicable: patronage, deferring to the monarchy and the name of the British Empire, which is a monument of exploitation and conquest."

The 1990s was a decade of tremendous output that reflected his championing of the underdog: Riff-Raff (1991), Raining Stones (1993) and Ladybird Ladybird (1994) presaged films set in Spain and Nicaragua, Land and Freedom (1995) and Carla's Song (1996) respectively, all dealing with the same basic theme – that of the hunger for justice of the ordinary man and woman – that underlie his early kitchen-sink tragedies.

My Name is Joe (1998), set in the working class tenements of Glasgow, is arguably his most rounded work to date, although some critics argue that Loach's recent penchant for softening the politics and sugaring the pill – with the likes of Bread and Roses (2000), Sweet Sixteen (2002) and Ae Fond Kiss (2004) – has paid dividends at the box-office.

The Palme d'Or award will no doubt thrust Ken Loach's name into the mainstream, but it's unfortunate that the debate about The Wind that Shakes the Barley has centred on its relevance to the current conflict in Iraq. Behind the overt gestures and dramatic socio-political statements lies a very good filmmaker indeed, a quiet master of his craft who insists, for example, on using actors from the hinterland of the setting of his films in order to ensure authenticity.

Ken Loach has been a humanist filmmaker for many years now; it's unlikely that any award, even one as prestigious as the Palme d'Or, will cause him to deviate from his path one iota.