Comfort the afflicted... and afflict the comfortable

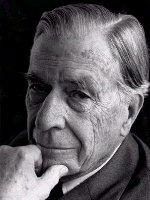

John Nichols looks at the influence of the late John Kenneth Galbraith, the greatest public intellectual of the second half of the twentieth century.

Had it not been for the accident of his birth in Iona Station, Ontario, John Kenneth Galbraith, the greatest public intellectual of the second half of the American century, would surely have been considered presidential timber. As it was, the man whose Canadian birth barred him from seeking the nation's highest office had to settle for shaping every presidency since that of Franklin Roosevelt – either as a trusted counsellor to the occupant of the Oval Office, a wise critic or, as was frequently the case, both.

One of the last veterans of the Roosevelt's epic first term – during which he worked with the Agricultural Adjustment Administration – he would go on to advise FDR's National Defense Advisory Committee and then to serve as an administrator of the Office of Price Administration, where the man who was as quick with a quip as he was with economic charts and tables noted that he "reached the point that all price fixers reach -- my enemies outnumbered my friends".

It will be his epigrams, his one-liners and his sharp asides that many of his friends will miss most about Ken Galbraith, who has died at age 97. The genius of the economics professor so long associated with Harvard and with most of the good – or at least tolerable – presidencies of the 20th century, was that he was never so impressed by his immense knowledge or his powerful positions that he could not find a humourous, and sometimes cutting, phrase with which to note the obvious.

When he was one of President Kennedy's most trusted aides – and, ultimately, the ambassador to India – Galbraith was dispatched to Vietnam to survey the country to which Kennedy was being advised by others to dispatch military forces. Galbraith, who tried harder than just about anyone else to avert the turn toward quagmire, sent back a memo in which he reflected on the difficulty of distinguishing "friendly jungle" from "Vietcong jungle" and asked, "[Who] is the man in your administration who decides what countries are strategic? I would like to ... ask him what is so important about this real estate in the Space Age."

As Galbraith biographer Richard Parker noted in his essential review of his subject's attempt to prevent Cold War hawks from convincing Kennedy and then Lyndon Johnson from expanding US military involvement in southeast Asia, it was in the fall of 1961 that, "Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith, then Ambassador to India, got wind of their plan – and rushed to block their efforts. He was not an expert on Vietnam, but India chaired the International Control Commission, which had been set up following French withdrawal from Indochina to oversee a shaky peace accord meant to stabilise the region, and so from State Department cables he knew about the Taylor mission – and thus had a clear sense of what was at stake. For Galbraith, a trusted adviser with unique back-channel access to the President, a potential US war in Vietnam represented more than a disastrous misadventure in foreign policy – it risked derailing the New Frontier's domestic plans for Keynesian-led full employment, and for massive new spending on education, the environment and what would become the War on Poverty. Worse, he feared, it might ultimately tear not only the Democratic Party but the nation apart – and usher in a new conservative era in American politics."

Parker's recent biography, John Kenneth Galbraith: His Life, His Politics, His Economics, is necessary reading, as are Galbraith's own books, particularly 1958's The Affluent Society, with its Keyneseian indictment of "private wealth and public squalor" in American life, and 1992's brilliant The Culture of Contentment, which offers what is still the best explanation of the contemporary crisis in its observation that, "The long years of high budget deficits when they were not needed made it seemingly impossible to initiate stimulating public expenditures when they were now needed. The celebrated tax reductions for the upper-income brackets and the accompanying economics in welfare distribution had substituted the discretionary spending of the rich for the wholely reliable spending of the poor."

The wittiest and wisest of "the best and brightest", Galbraith broke early and publicly with President Johnson over what had become the Vietnam War and helped the influential liberal group he had co-founded decades earlier, Americans for Democratic Action, move toward an opposition stance that confirmed that even Cold War liberals recognised the madness of engaging in a long-term ground war in southeast Asia.

Galbraith would serve as a distinguished father figure for the anti-war movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, lending his towering presence to student protests and the campaigns of insurgent Democratic presidential candidates Eugene McCarthy in 1968 and George McGovern in 1972. Over the ensuing years, he would remain a steady critic of the imperial endeavors that would rob the US treasury of the resources that could have built the great society.

Galbraith would serve as a distinguished father figure for the anti-war movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, lending his towering presence to student protests and the campaigns of insurgent Democratic presidential candidates Eugene McCarthy in 1968 and George McGovern in 1972. Over the ensuing years, he would remain a steady critic of the imperial endeavors that would rob the US treasury of the resources that could have built the great society.

Several years ago in a valedictory essay that drew together the vital themes of his long career as both an economist and as the Cassandra who warned of the overwhelming costs of misguided foreign policy, Galbraith observed, "We cherish the progress in civilisation since biblical times and long before. But there is a needed and, indeed, accepted qualification. The US and Britain are in the bitter aftermath of a war in Iraq. We are accepting programmed death for the young and random slaughter for men and women of all ages. So it was in the first and second world wars, and is still so in Iraq. Civilised life, as it is called, is a great white tower celebrating human achievements, but at the top there is permanently a large black cloud. Human progress dominated by unimaginable cruelty and death. Civilisation has made great strides over the centuries in science, healthcare, the arts and most, if not all, economic well-being. But it has also given a privileged position to the development of weapons and the threat and reality of war. Mass slaughter has become the ultimate civilised achievement.

"The facts of war are inescapable – death and random cruelty, suspension of civilised values, a disordered aftermath," Galbraith continued. "Thus the human condition and prospect as now supremely evident. The economic and social problems here described can, with thought and action, be addressed. So they have already been. War remains the decisive human failure."

The clarity of his vision led several generations of insurgent political strategists to imagine a "Galbraith for President" candidacy, only to be jarred back to reality by the fact that, while Galbraith had been a US citizen since the 1930s, the Constitutional bar on foreign-born candidates disqualified the most attractive contender from consideration. Few political realities frustrated Allard K Lowenstein, the boldest advocate for a 1968 Democratic primary challenge to Johnson than the fact that Galbraith, his friend and frequent ally, could not be the candidate. George McGovern, who made no secret of his esteem for Galbraith, would have been delighted to make the former Roosevelt aide and Kennedy ambassador his vice presidential running mate in 1972 – a selection that surely could not have hurt, and might well have helped, the Democratic cause of that year. And how amusing it would have been in 1984 if the mentally agile 76 year old Galbraith had been the Democratic nominee against his doddering 73 year old contemporary, Ronald Reagan. As it was, he would be boomed by liberals now and again over the decades as a potential candidate for the Senate from his adopted home state of Massachusetts. But it was never to be, perhaps because Galbraith's healthy ego told him that he was best suited for the top job.

Galbraith professed to be amused by the "Galbraith for President" talk, as he was by Canadian suggestions that he might want to come back and serve as that country's prime minister. But he did, with tongue planted only slightly in cheek, imply an interest in presidential politics that was more than merely academic. When the 200th anniversary of the Constitution was celebrated in 1987, American Heritage magazine asked prominent Americans to suggest how they would amend the founding document. Galbraith's reply: "My answer is obvious: That clause that excludes Canadians and others of foreign birth from the Presidency and, possibly, from the Vice-Presidency as well. My whole life was altered, as also, quite clearly, was the history of the Republic. Henry Kissinger, I cannot doubt, vociferously agrees."

A quite serious law professor Jonathan Turley would suggest some years later that Galbraith provided the classic argument for elimination the Constitutional restriction that "denied the nation some of our best and brightest."

When Austrian-born actor Arnold Schwarzenegger was elected governor of California in 2003, there was a flurry of talk about amending the Constitution in order to allow Americans who had been born beyond the nation's borders to seek the presidency. It seemed at the time that the best argument for the measure was the fact that Galbraith, at 94, was still physically fit, intellectually exceptional and as committed as ever to the liberal ideals that had powered the most successful Democratic presidencies – a combination that made him far more qualified not only than the current occupant of the Oval Office but than most of the Democrats who aspired to it.

With Galbraith's passing, we are left with one less counter to his observation that, "Politics is not the art of the possible. It consists in choosing between the disastrous and the unpalatable." Thankfully, we are left, as well, with John Kenneth Galbraith's wisest piece of political advice; his suggestion that: "In all life one should comfort the afflicted, but verily, also, one should afflict the comfortable, and especially when they are comfortably, contentedly, even happily wrong."

When Democrats nominate a presidential candidate who is as capable as Galbraith was of articulating that sentiment, the liberalism that our late economist so loved will indeed be resurgent.

John Nichols is The Nation's Washington correspondent

© 2006 The Nation