The unaffordable housing scheme

Tenancy in Ireland is a stepping stone. That's long been the idea, anyway: one rents til one buys, and god have pity on anyone not in a position to buy. Government policy throughout the boom was calculated to ensure tenancy could not be a viable long term choice for anyone wishing to have a roof over their heads, leaving, for most, only the option to purchase a home at a hyper-inflated price. Post crisis, not much has changed, says Tadhg O'Sullivan.

In RTÉ's first leaders' debate, on Valentine's day, the arrayed party kings were asked to respond to a question from a lady called Natasha about what they planned to do for people in mortgage arrears. Each of the five nominal leaders used Natasha's name repeatedly in their responses, as their advisors had advised. Natasha was assured, her fears personally assuaged from each wooden lectern - her friend would be okay, he wouldn't be evicted.

Natasha was one of the chosen few who got to frame RTÉ's questions for the five-way leaders' debate in the standard Frontline human-misery-with-a-face-and-a-name format. She was concerned about those in mortgage arrears, like her friend, a man in his fifties, who, having lost his job, was in trouble. He is not alone - all over the country people are facing the reality of huge mortgages from outside the situation in which they were taken on. Interestingly, RTÉ did not present us or the leaders with one of them, just someone who "had a friend".

What did the politicians have for this unnamed friend and his ilk, having engineered massive bailouts for those whose investments went wrong under the aegis of banking? What, under a new government, would be the fate of the mortgage holder Pat Kenny described as "benighted" ("in a state of intellectual or moral ignorance" - OED)?

The five men queued up to ensure the security of those who found themselves behind on mortgage repayments - Labour would "provide a guarantee to people...that you will not lose your home during this recession provided you are making a reasonable effort to pay your mortgage". Enda Kenny too was quick to side with the benighted, following up a summary of his plans to increase mortgage interest relief with a message for the banks: "In respect of those in distressed mortgages... owners have rights and banks had better understand that this is a deliberate and conscious decision by the Fine Gael party to help [owners]."

But Pat Kenny wasn't happy with such vague toughness - what if the bailiffs were coming? "Eamon Gilmore is saying he'll head them off at the pass... are you of the same mind?". "I don't think," replied Enda, "there's a party here that would not want to head them off at the pass." As the leaders lined up to outdo each other in guaranteeing bad loans (between sniping at each other as to who had done or supported exactly that in September 2008), one tweet summed up the absurdity - "Direct debits being cancelled all over the country from 1st March."

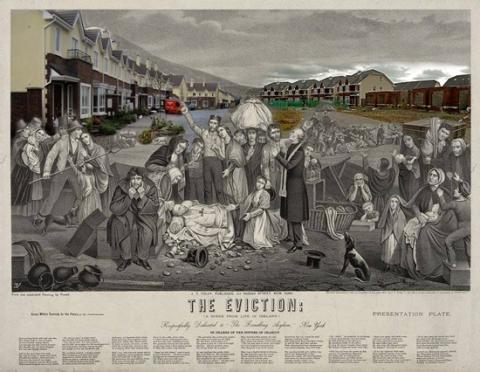

Micheál Martin took a turn on principle - "We must prevent reposessions of homes," before being trumped by Gerry Adams, who eschewed Pat Kenny's cowboy language to foreground the far more resonant imagery of 19th century Ireland that had been bubbling since the first mention of bailiffs: "As a matter of basic principle there should be no evictions in Ireland."

But there is a problem with co-opting this imagery for current usage. In the 19th century scenes etched on the romantic psyche of the nation, the scrawny, defiant peasant was not beyond the resort of interest-only repayments; the burly bailiffs were not the whip-hand of rash banks; the beshawled woman had not signed a 35 year commitment to repayments based on an inflated statement of earnings three years previously. These were tenants, and while their adversaries in the scene - the bogeyman bailiffs - were invoked by name in the five-way leaders' debate, their direct modern analogue were entirely absented from the discussion, as they have been from almost all political discourse in recent years in Ireland.

The likely next Taoiseach's line - that "owners have rights" - is worth scrutiny. He did not say that "homeowners have rights" nor did he go on to position these rights on a spectrum relative to those of the state, those of the tax-paying public whose money props up the banks he was addressing or the right to security for those who are not "owners". So instinctual was its delivery that it came across as unusually firmly and passionately held by a man whose statements typically lack personal conviction. As such it is a useful indicator of the priorities of a government entrusted with beginning to address the systemic flaws in housing policy as entangled with economic strategy.

The 2006 census records 145,317 privately rented homes in Ireland. The laws that govern their situation are set out in the Residential Tenancies Act (2004), a piece of legislation that was informed in part by the Commission on the Private Rental Residential Sector (2000). The Commission's brief included investigating ways to address the lack of security of tenure for tenants, while also making recommendations for increasing the supply of housing stock for rent, "including the removal of any identified constraints to the development of the sector". The report that followed set out the idea that after six months of occupancy, an entitlement to a further four years of security would accrue to the tenant. However, the recommendation, and its adoption in the subsequent Act, was rendered meaningless by a get-out clause for landlords who intend to sell the dwelling.

This clause, combined with the report's recommendation of tax incentives for investors in the sector and its framing of landlords as entrepreneurs ("...as a general principle, the business of providing residential rented accommodation should, where appropriate, be treated for tax purposes in the same way as other businesses"), makes this report a key text for those investigating the relationship between houses, unfettered property speculation and the economy in general in Ireland's property bubble.

In the bubble years, tenancy was the only option for a large portion of the population who, because of bad credit, low income, age or clear-eyed prescience could not or would not step on the rotting rungs of the ropey ladder. Spending their "dead money" on badly furnished houses and beige apartments whose very architecture seemed themed "temporary", this maligned demographic, so often characterised as homeowners in waiting ("Oh, you're renting still?") were afforded no security in law. Rented houses were not places to raise families or put down roots - they were waiting rooms for the slow to catch on; they were stopping points for peripatetic youth and the migrant margins. It was, and remains, an unshakable national cultural position. From time to time someone will mention that some 70 per cent of Swiss people live in rented houses, to be greeted with a look that says, "And the vast majority of Swiss men own guns - what's your point?" Near-universal home-ownership as an ideal is seen as a non-negotiable starting point for all mainstream conversations on housing in Ireland. If challenged, this position is backed up by recourse to our friends, the 19th century disposessed, before a deep, Celtic grá for the land is wheeled out as though its unquestionable veracity were enough to silence all argument.

But the dispossessed rallied under the banner of security. The land wars - the most remarkable and successful revolt in the country's history - were fought for the three Fs - one of which was not the First Time Buyers' allowance. And as for the deep grá for the land - if it exists it can only be to underpin the price typically exerted for land in this country, for only that would explain the willingness we have to part with it so regularly for inflated sums.

The clauses that hobbled the Residential Tenancies Act were an expression of the legal primacy of the right to sell housing quickly. With the Private Residential Tenancies Board (which came into being through the 2004 act) recognised to have been a failure in enforcing standards and transparency in the rental sector, the 2004 act can now be judged itself to have been a failure, providing nothing but a legal framework for landlordism and rampant speculation in the housing sector. By facilitating temporary revenue streams for those playing the market over time but allowing them to sell at a time of their choosing, the Act - in combination with a vast range of tax-breaks and grants - made housing a universally available sweepstake. Houses and apartments were the tickets and they could be bought and sold in the abstract, before they were even built - all the better so as not to have to deal with pesky tenants. Given that part of the brief given to the Commission on the Private Rental Residential Sector (2000) was to seek ways to increase housing stock for the rental sector, it is now clear that the Commission's report and the legislation that arose from it is severely outdated. We have no great need for new houses.

Absent from all debate about future Irelands of late has been a vision wherein this notional lottery is phased out and replaced with a policy on housing under which houses are primarily for living in. As the Finance Bill was walked through the Dáil like a rowdy drunk at a wedding who has finally succumbed to sleep, its elbows held by those keen to be seen to be helping, a notable absentee from its contents was the Section 23 scrappage scheme, announced in December's budget. The scrapping of this tax relief, which allows the write-off of the value of investment property against tax on all rental incomes, is a political timebomb that all parties seem to have agreed to ignore since it was kicked down the line last month. The scheme was a key element in the Fianna Fáil led trapezium-sceme that drew queues to docklands and flood-plains, inner cities and outer ring roads in the still-called "good times". The demographic affected on the investment side will lose out heavily if and when it is removed and the short-term politics of this election cannot get its head around the implications.

Section 23 is just a beginning - the very economic fabric of this country is woven with the weft of property speculation and nobody is willing to start picking at the threads.

Back at the "leaders' debate" the short-term nature of current strategies was best illustrated by Eamon Gilmore's contextualisation of his guarantee that nobody in mortgage arrears would lose their home on his watch - "These people are going to be back in business." "In the course of time we'll come through this recession." He seemed to see no need to deal with the systemic problem - that we have the infrastructure of a property bubble factory. Indeed, to listen to the three men in the middle, one would assume that bubbles and their manufacture were a viable long term industry for the country.

It is the speculative potential of returns on investment that inflates housing prices to bubble status. Price and utilitarian value are divorced and those with humble ambitions of security are forced into a speculators' market, mostly at the least unaffordable end. In the long-term event of a structural mortgage forgiveness programme, in which debts are written down by the state, these people will not be rewarded for their lack of ambition. Those who overstretched the most will gain the most. This will solve some problems but create a deep resentment amongst those not bailed out. Perhaps rather than repeat itself in this way the State might take a stake in this next bailout, by taking ownership, through its own banks, of houses under distressed mortgages and leasing them back to the occupants on 99 year leases. It is what has been quietly happening with bank repossessions anyway, albeit in short term arrangements - why not make the scheme official while allowing people to move by allowing leases to be traded on the open market. The framing of the leases could be a model for the wholesale reform of the rental sector, opening up tenancy as a realistic option for those who want nothing more than a home for life. The scheme would take a lot of working out and would perhaps be a hard sell to those who cleave to the speculator's dream and invoke mystical, ineluctable Gaelic drives in their passion for buying and selling houses. But a generation is coming up behind them who are watching this carnage and who have neither the money nor the yen for magic beans or get-rich-quick schemes. With open minds and a desire for stability and security in an age of deep uncertainty they might be persuaded by a system that offers some fixity in life, at a fair price, with the freedom to move on if they so wish. Perhaps if the scheme were marketed along the pithy, easily memorised, lines the Taoiseach-in-waiting is so fond of. The Three Fs of Housing, or something.

Image top Tadhg O'Sullivan.