THE TYRANNY OF ORIGINALITY

ONCE UPON A TIME there were flowers in fields and gardens, and trees and landscapes, and men and young girls sat on the ground underneath the trees and laughed, and made love. And where the land went into the sea waves broke upon the shore, and children played in the sand, and men and women walked along the beach. And the sun shone down on it all, and the wind blew, and clouds moved across the sky, and the leaves twisted and the trees swayed, and the surface of the water was troubled. By Bruce Arnold

And Painters painted all these things.

That was about seventy years ago. It worked after its fashion but was challenged by a movement in art which sought to see things differently, and see them in a new way.

What transpired was a major cultural revolution which in art gave birth to Cubism, which in turn gave birth to a succession of lesser revolutionary movements, the force of which was steadily attenuated by time, by geographical dispersal, and by the slow, inevitable, insidious fact that emerged: originality becoming a central requirement in art.

The need for it enslaves most artists. The existence of it removes virtually all possibility of objective criticism. There is no comprehensive range of criteria that embraces a situation where revolution has become the normal and desirable state; no constitution for art can be written; there can be no court of appeal. All that one is left with is the question of whether the object is well made, a question that never arose in art until all the other possible questions about art were blocked by the imposition of the slave-state of originality.

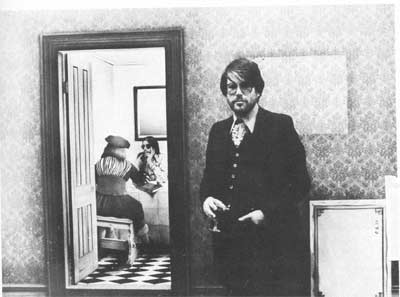

Photo Above: The Conversation, Robert Ballagh, twice, with Jan Verneer.

Yet there is a further absurdity: originality is infinitely rare in art, and though the urge is there the force of tradition is really what dominates and controls everyone. The other controlling force is the market consideration for the modern artist: the elite among painters and sculptors, if they make the necessary break-through, will sell to banks and businesses, art galleries, and collectors who build their houses to receive monuments to their wealth and fashionable taste.

Ireland is no less imprisoned in the cultural world which thus emerges, and this year's Living Art Exhibition, in the Douglas Hyde Gallery in Trinity College, is itself a monument to all the indiscretions and mistakes which must emerge from so topsy-turvy a background. Geroge McClelland, for example, has an assemblage called

"The Healing Screen". Its theme is medicine and religion. Meticulously constructed out of "found objects", it is a stimulating and entertaining piece of work. It is not art, it

has very little to do with art. It is a painstaking intellectual doodle, highly derivative, well constructed, worth doing for fun and provocation.

That it should be included in the Irish Exhibition of Living Art is open to serious question. That it should have been bought by the Friends of the National Collections of. Ireland for the collection of modern art.in the Hugh Lane Gallery is an absurdity. George McClelland is an enterprising ex-policeman from Northern Ireland in his late forties who formerly ran an art gallery, then moved to Dublin to deal in art, and then enrolled as a student in the National College of Art. To have been institutionalised with his first work is wonderful for George McClelland, who is an agreeable chap whom I have known for several years, and whom I like.

But I am not half-way through this review in order to help people I like. His instant assumption -of a new status is an object lesson in the absurdity that derives from a permanent, if artificial, state of revolution where no standards apply, and where there is therefore no argument.

Another example is Paul O'Keefe's "Poison (For Max Nordau)", a large abstract sculpture, also bought by the Friends of the National Collections of Ireland for the Hugh Lane Gallery. The work is an interesting exercise in abstract metal and concrete construction by another, much younger student in the college. It shows that the college is teaching some technical skill and is at least opening the eyes of students to what is happening abroad. It shows nothing else, and again its presense, and even more its purchase for the State, is an absurdity.

Much less absurd is the work of painters like George Potter, Robert Ballagh, Charles Tyrrell, Jack Donovan,Fergus Lyons, Charles Cullen, Charles Brady, Tim Goulding, Martin Gale, Danny Osborne and Charles Harper. They are more or less masters of their own destiny; their feelings as well as their technical competence are palpable; they have a recognisable and consistent "voice" which amalgamates tradition and the individual talent. The price they pay for this is loss of originality; the very recognisability of their work is becoming a handicap. At the same time they are not entirely free men; with one or two exceptions they are still shaking off the shadows of their masters. This is not a fault; just a handicap.

The majority of them will feel their way through to survival of a kind. They have learnt to handle paint, and have put it to a purpose that is capable of arresting and holding, for a while, imagination, response to colour and texture, feelings of joy or amusement, a sense of space and light. lt is a flag of talent carried through a permanent wasteland of revolution.

There are younger men who show promise. There is both feeling and precision in John Murray's "Recollections", There is promise in Fidelma Massey's sculpture and in "The Lifesize London Tie" by John Curran. The hanging and arrangement of the exhibition is impeccable: the works have been subjected to the restraints of architecture and the regimentation of the glowing atmosphere of "taste" that pervades the Douglas Hyde Gallery, Exhibitions have themselves become artistic "events", and the works too often look as if they were chosen for the spaces they occupy rather than the merits they contain. But since no one can really judge the merits this is of small importance. Where have all the flowers gone? Girls, young men, soldiers, revolutionaries, graveyards, ... perhaps, in the 'natural passage of time, the flowers will bloom again.