Sundays, Bloody Sundays

The advent of The Sunday Tribune promises a newspaper battle which can only be of benefit to the bored Sunday reader. Vincent Browne has more.

Commentators who like to gulp with astonishment at the phenomenon of that peculiar institution, the Irish Sunday newspaper, have had much to gulp about in recent weeks. The PMPA take over of the ailing Sunday Journal and the impending rise of the Sunday Tribune from the ashes of Hibernia brings to five the number of newspapers battling for space outside the church gates on Sunday morning.

At present, over a million Irish newspapers are sold each Sunday, which is more per head of population than in Sydney" Bonn, New York and just about every other major capital. New York, for instance, has only three Sunday papers to Ireland's five. Only Tokyo, with 11.8 million people, equals the Irish figure.

At present, over a million Irish newspapers are sold each Sunday, which is more per head of population than in Sydney" Bonn, New York and just about every other major capital. New York, for instance, has only three Sunday papers to Ireland's five. Only Tokyo, with 11.8 million people, equals the Irish figure.

The homogeneous population and the geographical compactness which facilitates distribution go some way to explaining the phenomenon. One other seldom admitted fact goes' even further: the Irish Sunday newspapers are appalling. Bereft of all but the most obvious and easily gathered news, tame, predictable, with features rarely rising above the level of the breathless confessions of ex-nuns, the Sundays are individually unattractive. As a result, most readers have to buy more than one, if not all of them, to get a product which even then comes nowhere near the quality of papers such as the Sunday New York Times.

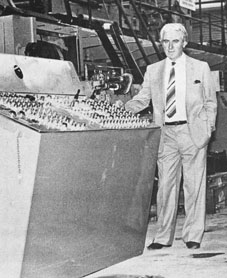

Hugh McLaughlin's Sunday Tribune aims to change that by hiring the best columnists, journalists and writers in the country. No expense is being spared in gearing up for the new paper and the pressure will be on McLaughlin's editor, John Mulcahy, to deliver the goods. As one senior newspaper executive remarked: "There's always room for a better product, if it's a better product."

Hugh McLaughlin, proprietor, and John Mulcahy, editor, are unlikely bedfellows. Mulcahy has been a full-time journalist for a dozen years, following his takeover of Hibernia in 1968. Previously he had been a director of the Smith Group and had pursued a part-time career in business writing. Despite his authoritarian reputation for running a tight ship at Hibernia, demanding loyalty and commitment above the norm from his staff, his paper acquired a liberal and sometimes radical aura. The paper maintained a consistently liberal line on the North, repression, prisons, women's liberation and industrial relations.

Hugh McLaughlin's career has been somewhat more chequered. Born and reared near Ballybofey, Co. Donegal, the son of the local station master:he went to Dublin in the late 1930s and entered the clothing manufacturing and retail business. A decade later he bought a small printing press, sold his clothing interests, and got involved in publishing.

One of his ventures was the Farmer's Journal, one of the outstanding successes in Irish publishing in the last thirty years. He also spawned a series of trade Journals of uniformly bad quality. In the early 1950s he sold the Farmer's Journal to Paddy O'Keefe and John Mooney and used the proceeds to buy a new printing plant which became the basis of the infamous Creation Group.

McLaughlin's success in setting up the Sunday World was overshadowed by the debacle of the Creation Group collapse. In the wake of the collapse, it was discovered that employees' tax and union contributions, stopped at source, had not been paid. Even today, many of the Creation workers are owed money by the collapsed company.

In negotiating with the printing unions to set up the Sunday Tribune McLaughlin found that the ghost of Creation is still at his shoulder. Although it is the Creation company, and not McLaughlin, of which McLaughlin owned only 15 per cent, that owes the money to the unions' members the unions entered the negotiations with barely concealed grins of expectation.

The success of the new Sunday paper, then, depends on the mating of the liberal editor and the hard nosed businessman.

Ostensibly, the decision to start the Sunday Tribune was made when Hibernia faced financial ruin because of the Fr. Egan libel case and Hugh McLaughlin took the opportunity to take over the Hibernia stable and put it in a different kind of race.

The Egan case was indeed serious, with Hibernia having to pay £17,000 in damages and as much again in legal fees. However, John Mulcahy had approached McLaughlin some months before the Egan case and asked if McLaughlin's new printing plant in the industrial estate at Sandy ford could print a Sunday newspaper. McLaughlin replied that that was precisely his intention. From there began the negotiations which resulted in the Sunday Tribune.

When planning the Sunday World in 1973, says McLaughlin, it was a toss-up whether the new paper would be a popular one or a paper aimed at the ABC 1 readership. He decided on the pop format because of the greater availability of journalistic talent for such. The probability that there was also an "upmarket" newspaper gap was kept in mind.

Late last year McLaughlin's son-in-law, Sean Collins heard of the availability of a printing machine owned by The Economist in London. This machine, one of the most advanced in the business, was used to print The Economist and Newsweek and is reputedly capable of high quality colour reproduction on newsprint. The machine, along with its ancillary equipment, forklift trucks etc., and the premises to house the plant, cost McLaughlin a total of £900,000. The machine is owned by Gemini Printing Co., of which McLaughlin is a 100 per cent shareholder.

A circulation of 80,000 will be aimed for, at 25p a copy, and £100,000 is earmarked for promotion. Planning to invest £350,000 in all in the paper, in addition to the money spent on the printing plant, McLaughlin reckons the venture can be made profitable in two years.

It is the Sunday Independent, with the hog's share of the upper end of the market, which is most vulnerable to the

advent of the Sunday Tribune. The Independent Group has for some time been dissatisfied with its performance and market research has indicated reader dissatisfaction with its organisation and presentation. An attempt at reform has been going on, without much evidence of success, for the last twenty months.

Independent management went into a panic at the success of the Sunday World in 1973. The then editor, Conor O'Brien, who had come over from the Evening Press in 1970, came under a lot of pressure and an abortive relaunch was foisted on him in the autumn of 1975, at a cost of £100,000. Typically, the most prominent feature of the relaunch was a serialisation of the book Edward the Rake, and unsurprisingly, the decline in sales continued.

O'Brien had in fact been a courageous editor and it was during his tenure that Joe McAnthony engaged in a series of investigative stories, the most notable being that on the Irish Hospital Sweep Stakes.

In February 1976, without giving a great deal of thought to exactly what they wanted him to do with the paper, management appointed Michael Hand editor. It became apparent shortly after his drafting in from the Sunday Press in early 1975 that Hand was being groomed as editor, primarily because there was no alternative available to take over from O'Brien. A marvellously intuitive journalist, with a good instinct for the odd political scoop that came his way and considerable writing flair, Hand had been brought into the Indo to give a more popular, earthy tone to a paper that had gone desperately dull. Hand predictably sought to popularise the paper in an attempt to withstand the challenge of the Sunday World. With almost no staff, a house agreement with the NUJ which effectively debarred any serious journalism and a skimpy budget for outside contributors, Hand did well to reverse the decline in sales, but at the expense of any quality the paper had under Conor O'Brien.

It has been this process which has left the Sunday Independent now dangerously vulnerable to the McLaughlin challenge. Hand himself is not geared to editing a quality newspaper, indeed it is at least arguable that his talent as a journalist has been wasted by his being appointed editor at all. Furthermore, he has a staff on the paper now very set in its ways and geared for the middle of the road soft "pop" journalism which has dominated the paper in the last few years.

In addition, there are not many on the staff of Independent Newspapers who could do anything journalistically to help out. Recruitment policies have been inept over the last several years which means that the standard of journalism in the Group as a whole is very low.

The Sunday Independent is of vital importance to the Independent Group. Of the three newspapers it earns 80 per cent of the profits and therefore a threat to it is a threat to the entire outfit.

Of the other three Sundays, the Sunday Journal is the weakest, still pulling itself together after its near demise. The lightning transition from the farmer's Sunday reading to a basically urban, and especially Dublin, "family paper' you can be proud to be seen with" is still being consolidated. The paper is losing a!l unspecified amount of money each week, but this is being reduced. The Sunday Press seems determined to remain 'regally above it all. "We think people are buying us because we are the best and everybody else competes with that", says editor Vincent Jennings, without any attempt at false modesty.

While continuing to envy and taunt the supremacy of the Sunday Press, Kevin Marron's Sunday World has had recently to take a few side-swipes at the Sunday Journal. ("Nobody Does It Better"). "Even a coloured tabloid toilet roll" can be opposition and has to be taken seriously, says Marron.

Hugh McLaughlin believes that the new venture can be more financially stable than the Sunday World as the quality market is less volatile. He sold his 54 per cent of the equities in the Sunday World, in 1978, for the equivalent of

£1 million, the paper having started a few years earlier on a capital basis of £70,000. A takeover bid had been made the previous year by Michael Smurfit on behalf of himself and Tony O'Reilly. Though this failed, O'Reilly was successful in 1978.

McLaughlin believes that it will be possible to determine the success or failure of the Sunday Tribune within a matter of weeks and that therefore it is essential that the package be right from the start. There are extreme doubts about the feasibility of tl1is, given the time and people involved.

McLaughlin's options on an editor for a quality paper were limited. And Mulcahy, in spite of his "radical" image, had obvious qualities for the job. Certainly the choice gave McLaughlin a foothold in serious journalism that he previously lacked. Mulcahy, who was used to a free hand (and used it without restraint) at Hibernia, will have editorial freedom within the limits agreed with his boss. However, there have already been some rather seamy backstage manoeuvres in an attempt to dump one Hibernia journalist. It is unclear whether tl1e move was initiated by McLaughlin in support of his "there will be no radical politics in the Sunday Tribune" statement, or by Mulcahy's discomfort with the strong NUJ principles of the journalist involved.

Mulcahy's poor reputation as an employer may militate against the new paper as much as McLaughlin's subsequent survival as a millionaire after the Creation debacle. Hibernia has had a very high staff turnover in the past few years and Mulcahy failed to hold on to many of his best journalists, including Brian Trench, Joe Joyce, Niall Kiely, Daragh McDonald, Andy Pollock, Ed Moloney and Jack Holland. While maintaining a courageous line as editor his concept of journalism as an intelligent summation of the known facts, mingled with informed opinion, and usually conducted almost entirely by phone from the office, results in a style that may lack the investigative edge required by a serious paper.

The dying Hibernia has substantial contributions to make to its Phoenix: a solid financial section, a book section which in spite of, or even because of, its elitism and idiosyncrasies holds the allegiance of even such as Fr. Egan, the country's best film column, and a reputation for in. dependence and courage.

However, even the most well managed and well edited operation may find it difficult to cream off an 80,000 readership from the top of the market and McLaughlin may be forced to aim at a higher circulation in order to get the required penetration in the AB market. Mulcahy's lack of experience here (for example, in what are for a Sunday newspaper essential ingredients, sport and entertainment) may. be a stumbling block.

Getting the right mix within the pages of the new paper may be a problem, but no more difficult than the mixing and mating of the publishing industry's oddest couple, McLaughlin and Mulcahy. Whatever the result, the ripples from the Sunday Tribune's jump into the stagnant pool of Sunday newspapers can only have a beneficial effect on the

editorial standards of a branch of publishing that has been threatening to smother in its own smugness.