The Scandal of the Mental Hospitals

Over 14,000 people, more than the population of Kilkenny, live in mental hospitals in Ireland. Most of them live in conditions of squalor and dilapidation utterly inadequate for their therapeutic needs. And because of deliberate Government action these conditions are now going to worsen. Helen Connolly reports on the dire state of Ireland's mental health facilities.

There is to be a decrease in the level of real current expenditure on the psychiatric services of over £2 million this year (from £65m. to £63m. in 197y terms). All capital projects not approved for commencement in 1979 have been halted. This is in the context of a situation in the psychiatric services, described by Professor Ivor Browne, of St. Brendan's Hospital, Dublin, as "near collapse" .

Over 90 per cent of psychiatric patients are in the 36 public psychiatric hospitals around the country and about 10 per cent of these are attached to acute units where conditions are relatively good. But for the remaining 11,000 patients "catered" for in the public hospitals conditions are simply atrocious.

In an investigation of the state of mental hospitals throughout the country, which included visits to 12 of them, we have found that most of the larger hospitals are in a state of physical disintegration, oppressive congestion, demoralisation, often squalor and inadequate staffing, and that conditions were entirely inadequate to begin to cope with the problems of the patients. Most of these patients are in the literal sense outcasts from society. 10,000 patients are long stay and most of these will die in hospital, having spent 25 years and more - often over 60 years - in the same hospital and even in the same ward. Four out of five of them are single and the vast majority of them never receive a visit.

In an investigation of the state of mental hospitals throughout the country, which included visits to 12 of them, we have found that most of the larger hospitals are in a state of physical disintegration, oppressive congestion, demoralisation, often squalor and inadequate staffing, and that conditions were entirely inadequate to begin to cope with the problems of the patients. Most of these patients are in the literal sense outcasts from society. 10,000 patients are long stay and most of these will die in hospital, having spent 25 years and more - often over 60 years - in the same hospital and even in the same ward. Four out of five of them are single and the vast majority of them never receive a visit.

Over 2600 of the 14,000 patients m psychiatric hospitals are mentally retarded and are literally “dumped” there because of the inadequacy of proper facilities for them elsewhere. The psychiatric hospitals are entirely unsuited to the needs of mentally handicapped people and arguably further add to their retardation, while contributing to the chaos and demoralisation f the psychiatric hospitals.

More than one in three psychiatric patients are over 65 and over 2000 of them are over 75, yet these hospitals are entirely unsuited to any form of geriatric care and clearly a greater number of them shouldn't be there at all. Many old people are admitted to psychiatric hospitals on the recommendation of GPs "sympathetic" to the difficulties of relatives who are unable to cope with the aged. Unsurprisingly, the great majority of the 14,000 psychiatric patients are drawn from the poorer sections of the community.

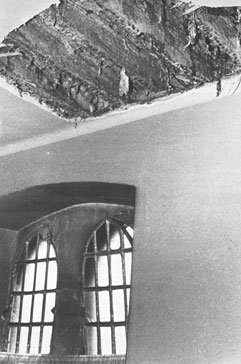

A ceiling collapsed on a sleeping patient in St. Brendan's Hospital, Dublin, in April of this year, revealing dry rot beneath the roofing (see photograph above). The building in question had been condemned sometime previously but it is still used as part of the hospital complex, while slates and bricks regularly fall to the ground. Within the last few months, some of the patients have been moved from this building but some 80 patients are, at the time of writing, still housed there, including geriatrics. The general condition of St. Brendan's is such that Dr. Ivor Browne estimates that it would take a staggering £10,000,000 even to maintain the buildings in their present dilapidated condition.

Conditions of similar dilapidation are common to psychiatric hospitals throughout the country - many of the chief psychiatrists advocate the demolition of their hospitals, rather than any attempted renovation, so great is the disintegration. Dr. Ivor Browne fears that the attention of the Government will be drawn to the plight of mental patients only when the dilapidated buildings at St. Brendan's actually collapse and patients are trapped underneath the rubble.

At St. Ita's, Portrane, mentally handicapped patients have, for many years, been housed in huts which were built at the beginning of this century to accommodate extra patients. Two of these huts (see photograph) are irreparably dilapidated while all are condemned as serious fire hazards. Shortly after Magill's inspection of this hospital, all but one of these huts was closed down. Lack of alternative accommodation for these patients does not permit the immediate evacuation of this hut.

Throughout the big hospitals the areas for the disturbed psychiatric patients and the mentally handicapped are generally the most inferior. Mentally handicapped patients in Our Lady's Hospital, Cork, occupy a unit which resembles a tenement, long overdue for demolition.

A pervading stench of urine, excrement and sweat confronts the visitor to the sleeping areas of many of the psychiatric hospitals in the country, most notably Our Lady's Hospital, Cork, and sections of St. Brendan's Hospital, Dublin.Nurses in several hospitals report patients suffering from pressure sores and urine rashes, which go undetected for long periods.

Thousands of patients exist for periods of between twenty and sixty years of their lives in conditions of simple squalor. Many of the day rooms are filthy, especially during wet weather. Patients are expected to undertake much of the cleaning themselves and many of them are clearly incapable of such activity. Conditions are worst in Our Lady's Hospital, Cork, where three quarters of the units have no full time cleaner. One of the nurses has described the conditions there to us as "barely above lice level and difficult to maintain at that" .

Many patients sleep in beds which are broken and with bedspreads and sometimes sheets torn and dirty. Virtually all of the patients are appallingly dressed - most hospitals work on a half yearly replacement of clothes but dresses and suits are often worn for years on end. The situation is worsened by the arbitrary operation of the laundry system - patients invariably fail to get their own clothes back following washing; and sheets regularly return to the beds still stained. In St. Brendan's hospitals mounds of linen are allowed to accumulate in the wash rooms. Given that a great many patients are incontinent this practice worsens the stench.

The provision of adequate amounts of hot water is a serious problem in many of the hospitals and the plumbing system in any event is suspect in buildings of well over 100 years old. In St. Patrick's Hospital, Castlerea, burst pipes have caused water to flow continuously onto the floor of the wash areas. Apart from these factors, the general conditions of most of the hospitals are depressing. Most of the inner walls are of limestone composition and are cracked and blistering, many of them don't have even a trace of paint.

In contrast conditions in sections of St. Brendan's Hospital, Dublin, St. Ita's Hospital, Portrane and St. Brigid's Ballinasloe, are in relatively good condition. Some renovation has taken place, wards have been painted, furnishing replaced etc. But these "renovated" areas are the exception.

There is also a striking difference between male and female wards. Conforming with the outside world's sexist practices, the women's quarters are often bright and clean in contrast to the drabness and often filth of the men's wards. In some cases it is possible to walk directly from a cheery women's ward into a squalid men's. This contrast is partly explained by the practice whereby male nurses are confined exclusively to men's wards and female nurses' exclusively to female wards.

One of the reasons for the pervading squalor is the priority given to acute units in the allocation of finance. For instance in St. Brigid's Ballinasloe, £500,000 was spent on renovating the acute unit, used by short stay patients, who comprise only one in five of all patients in the hospital. In the long stay section, where the other four out of five patients are accommodated, a meagre £50,000 has been spent on minimal improvements - it is these patients who are otherwise also most neglected.

Eating is the sole diversion of many psychiatric patients. They rush enthusiastically to meet the tea trolley, some of them grabbing as much food as they can stuff into their pockets and mouths and then retiring to a corner to dip thick slices of bread into a mug of tea. Lunchtime is the highlight of the day - for almost an hour, at least there is something to do.

Patients can be seen in all hospitals wandering aimlessly about, sitting in day rooms staring into space or at the television set, sometimes showing only the test card. Canteens and shops for use by patients provide a hangout but these dilapidated and filthy surroundings offer no release from their habitual environment. Patients wander into the wards to lie on their beds and get away from the constant proximity to other patients. They roam up and down the corridors, generally the most run down areas of the big hospitals since all available finance is spent on living quarters.

A small proportion of all mental patients is engaged in cleaning and cooking and farming jobs. There are occupational facilities in all hospitals, but the great majority of patients never uses them. The elderly, the very disturbed and the mentally handicapped are not suited to the jobs carried out at these units and so they remain in their quarters all day, dependent on the once-a-week visit of a therapist and on nurses to provide some means of diversion.

Therapy units where handicrafts and industrial jobs are carried out provide an atmosphere totally different from the hospital environment for those few able to attend. The remainder of patients eagerly seek the attention of nurses to bring them for walks, card games or music sessions.

Patients' routine is disrupted by the working pattern of nurses which involves a three-day on and a three-day off rota, and consequently a steady pattern of diversion for patients is difficult to arrange. Throughout the hospitals nurses were seen to be occupied with arranging patients for meals, dispensing medicines, attending to paper work, and generally keeping a watchful eye over their patients - little effort is made at recreation for patients who are not willing or able to make the effort to do something themselves.

The task of occupying patients is rendered more difficult by the necessity to mix various types of patients through lack of adequate space. Patients of sixteen to sixty years are likely to share the same living quarters; mentally handicapped and mentally ill may sleep and eat together. Idleness becomes a way of life for patients who have known nothing else for very many years. A women of forty years was taken out of 81. Brigid's Hospital by her cousin. For twenty years she had become so accustomed to idleness that on reaching the house she immediately got into bed and refused to leave it until she was eventually returned to the hospital.

A number of patients in hospitals visited were seen to eagerly approach nurses with enquiries as to whether relatives had been in touch with the hospital to take them home. They have been asking the same questions daily for years but if and when they are released, normal active life is beyond their capability.

St. Mary's Hospital, Castlebar, is capable of catering for 450 patients, according to chief psychiatrist, Dr. Gilvarry. There are 636 patients in the hospital. This situation is typical of most of the psychiatric hospitals throughout the country, although a significant improvement has been made in the last 15 years. For instance, there were over 1000 patients in the Castlebar hospital in 1964.

The most striking manifestation of overcrowding is the congested dormitories, where beds are packed so closely together that, in some cases, they have to be moved one by one along a line at night for patients to get into them. This overcrowding is worst in St. Brigid's Hospital, Ballinasloe. At St. Loman's Hospital, Dublin, because of a shortage of space a billiard room is now being used as a ward. The toilet nearest to this room is 50 yards away. At this hospital a recreation room measuring 14' x 28' (no bigger than a large sitting room) caters for 70 patients.

According to one of the nurses at St. Loman's, Peter Storey, patients often wander around the hospital at night looking for a bed. Often, overflow patients are accommodated in nearby Killardin House, which is unsupervised. Recently a patient set fire to Killardin House at night and another male patient jumped from a top storey window.

One of the consequences of the overcrowding is that patients have not even the most basic privacy, which adds further to their degradation. Many don't even have a locker but then a greater number of patients in psychiatric hospitals have absolutely no personal belongings.

Overcrowding is also very apparent in the dining halls of most of the hospitals. The situation is exacerbated by the poor standard of crockery, although the food itself is ample if institutionalised. At Our Lady's Hospital, Cork, 200 patients congregate for meals in one dining hall. The food is eaten with speed from plastic plates and chipped crockery, while 50 pots of tea are consumed at each sitting. Similar conditions apply in St. Brigid's hospital, Ballinasloe.

While in some of the Dublin hospitals eating conditions are less oppressive, as there are small dining halls near the sitting rooms in individual units, there are numerous complaints of the food being cold by the time it arrives from the communal kitchens. Another facet of overcrowding has to do with toilet and bathing conditions in many hospitals. For instance in St. Loman's, a unit catering for 40 patients has one bath, four urinals and four wash-hand basins.

The overcrowding, prevalent in so many of the hospitals, has also significance in terms of a fire hazard. It is of course true that even in the best of circumstances it would be simply impossible to evacuate all but a fraction of these people. The greater proportion of them are old and infirm and could not move quickly without assistance.

The inadequacy of the system in the event of fire is underlined by the inability of the system to permit the patients to be helped into the open air on hot summer days - facilities are inadequate to accomplish the operation even over the space of a few hours. Whatever chance there might be of getting old, infirm people out of third storey wards, it is rendered immeasurably more difficult by the congestion in many of the dormitories. If beds have to be shifted to get patients into them, it is unthinkable what would happen in the event of an emergency.

Many psychiatrists advocate the establishment of designated centres to care for the treatment of alcoholics. These patients account for almost thirty per cent of annual admissions. More than one third of the 7,000 people treated for alcoholism annually use the private hospitals, but their presence in public psychiatric hospitals contributes considerably to the problem of overcrowding.

Our society uses psychiatric hospitals as "dumping grounds" for many of our old people. As mentioned earlier, medical general practitioners frequently recommend admissions to psychiatric hospitals for old people, simply on the grounds that their relatives are having difficulties in coping with them.

These hospitals are absolutely unsuited to the treatment and care of old people. There are no geriatric services available in these hospitals and this is in spite of the fact that over a third of all patients there are over 65. There is a great deal of doubt about the suitability:of these institutions even for the treatment of senility. The mixture of old people who may occasionally be senile with mentally handicapped patients and schizophrenics highlights the inappropriateness of these hospitals for the aged.

These hospitals are absolutely unsuited to the treatment and care of old people. There are no geriatric services available in these hospitals and this is in spite of the fact that over a third of all patients there are over 65. There is a great deal of doubt about the suitability:of these institutions even for the treatment of senility. The mixture of old people who may occasionally be senile with mentally handicapped patients and schizophrenics highlights the inappropriateness of these hospitals for the aged.

There are 2,680 mentally handicapped patients in mental hospitals because there are not enough special residential units to accommodate them. "These patients suffer the greatest injustice in the present system of health care," according to Mrs. Annie Ryan of the Association for the Rights of the Mentally Handicapped. She explains, "the mentally handicapped function at a level lower than those people with an average or higher intelligence quotient - mental illness and low intelligence are two different problems."

The term mentally handicapped is used to describe "those who, by reason of arrest or incomplete development of mind, have a marked lack of intelligence and, either temporarily or permanently, inadequate adaptation to their environment" (Commission of Inquiry on Mental Handicap I965). Residential care for the mentally handicapped is highly contentious, since 52 per cent of the mentally handicapped for whom residential care is provided are accommodated in mental handicap centres. The remaining 41.6 per cent are catered for in psychiatric hospitals (33.7%) and in geriatric homes (7.9%).

At a Seminar convened by the then Minister for Health, Mr. Brendan Corish, held in Waterford in 1975, it was stated that, "the Minister has already decided that this (mental hospital) is not a suitable place for the care and treatment of the mentally handicapped and this is the view of psychiatrists in general'. Five years later, this dilemma has not yet been resolved.

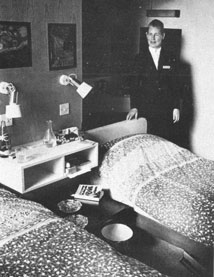

Since the late 19th century, patients whose families could afford the fees have been sent to private hospitals. In Dublin, St. Patrick's and S1. John of God's date back to that period, both in excellent decorative and structural order. The eleven private psychiatric hospitals in the country have approximately 1,050 beds between them, each year used by some 4,500 patients at a weekly fee of about £200, of which up to £60 is paid by the Government, depending on the type of private hospitals involved.

In contrast to the public hospitals, private hospitals do not cater for long stay patients. More than half the patients in private care have been hospitalised for less than a year, as compared to 20 per cent in public hospitals.

In contrast to the public hospitals, private hospitals do not cater for long stay patients. More than half the patients in private care have been hospitalised for less than a year, as compared to 20 per cent in public hospitals.

A quarter of patients have been hospitalised for over five years in private hospitals, as against 60 per cent in public units. Many patients who fail to recover at private hospitals or who can no longer afford the fees are sent to large public hospitals.

Nursing Staff salaries and work routine arrangements have caused psychiatric hospitals to be under a constant threat of strike for a number of years. The June industrial dispute has resulted in psychiatric nurses achieving an annual training salary of £4,400 with a basic of £5,400 when qualified.

The three areas of disquiet remaining are regarded by Professor R. J. Daly of Cork as a major hindrance to the care of the mentally ill: refusal by nurses to change the system whereby promotion is based on seniority rather than on professional skill, refusal of male and female nurses to work together and the roster system of working which involves twelve hours on Nursing staff at St. Brigid's, Ballinasloe duty and twelve hours off for a three day stretch. Some nurses claim that these problems could be overcome by offers of cash, that the pattern of demanding more money for a change in their system has been set out for them by their superiors in the service.

Both nursing staff and psychiatrists agree that nurses are urgently in need of retraining courses and also that under staffing is a problem in many hospitals. At St. Ita's, Dr. McGuinness points out that 470 nurses are insufficient to look after the 1,130 patients there, but this is primarily caused by the rosier working system of the nurses.

Nurse Peter Storey of St. Loman's complains that nurses must work extensive overtime, while nurses undergoing Post graduate training are used for lengthy periods of night duty and consequently miss lectures. Worse still, school leavers coming to the hospital to train are used to do the work of qualified nurses and at the time are denied adequate lecturing facilities.

Dr. Ivor Browne confirms this, but states that an equally pressing problem is the need to initiate a total in-service training scheme for all psychiatric staff. At present students are likely to learn from nurses who have acquired bad habits. A nurse, in Cork pointed out that he and other nurses have to rely on new nurses coming into the service to learn from them the latest methods of using drugs.

Ireland's hospitalisation rate of 26,000 admissions per annum is two and a half times greater than the rate in England and Wales. This reflects the Irish trend of indiscriminately using mental hospitals as dumping grounds for the mentally handicapped and geriatrics, rather than a higher incidence of mental illness.

Preventive facilities in the form of adequate screening of patients and sufficient supply of day centres to prevent unnecessary hospitalisation are grossly lacking. Rehabilitative service such as workshops and hostels or group homes to reinstate ex-patients back into society rather than re-admitting them to hospital (60 per cent of all admissions are' re-admissions) are equally in short supply. So long as the prime source of psychiatric care is located in the psychiatric hospitals, the incidence of mental illness is not reduced significantly.

Since the Health Board first drew up plans for the services in the mid sixties, a certain amount has been achieved. By classifying patients according to their therapeutic needs and relocating them as far as geographically possible to geriatric, mental handicap and psychiatric areas and finding homes for those not in need of hospital care, the population was reduced from 20,506 in 1960 to today's figure of about 14,000.

Reforming the law so as to ensure that nobody is detained unnecessarily will not alter the reality of this situation. A law which involves "detention" and "parole" is urgently in need of reform but updating the theory will not solve the problem of finding alternative and improved facilities, nor will it bring about an improvement in atrocious physical conditions.

"All waste must be eliminated."

Michael Woods, Minister for Health, in a letter to Dr. J. Corr, Chairman of the Southern Health Board, explained that, "in the difficult economic circumstances prevailing it is necessary to impose constraints on public expenditure generally and that. . . the overall allocation for health services was settled taking that consideration into account." The Minister acknowledged that the health board "will be faced with a very difficult task in deciding where the necessary economies will be found."

The bureaucratic machine translated this Ministerial message into concrete terms. The Chief Executive Officer of the Southern Health Board, Denis Dudley, for instance, in a letter of March 26, 1980 to the members of his board, defined in practical terms what constraints on public expenditure were, as far as the psychiatric services were concerned - "it will mean a reduction in spending on furniture, crockery, bedding, clothing, heating, lighting, medicines, medical appliances, x-ray, pathology, travelling expenses, stationery, and telephones. "

And in a phrase that must have seemed ironic to many in that health board's psychiatric services, he remarked, "all waste must be eliminated and spending restricted to essentials. "