The real public sector

The long-running project whereby a wedge is driven between private and public sector workers, as if each was a separate species (and with the defining characterisitics of the latter a tail and pointy horns) has had a fairly simple outcome, as Hugh Green writes below, and that is 'to mobilise animosity among disaffected and hard pressed workers employed in the private sector...so that they seek, via the assault on the public sector, to drive down their own wages, working conditions and social provision.' Meanwhile, overlooked, buried, ignored and absent from all discussion of public v private is any mention of the fact that most of the people who work in the public sectors of health, education and public administration are women. Because once that is factored into the argument, suddenly a space opens up in which to point out that this is not simply an argument about efficiency, and the valour of working sixty hours a week, it's an argument about power, patriarchy, and misogyny.

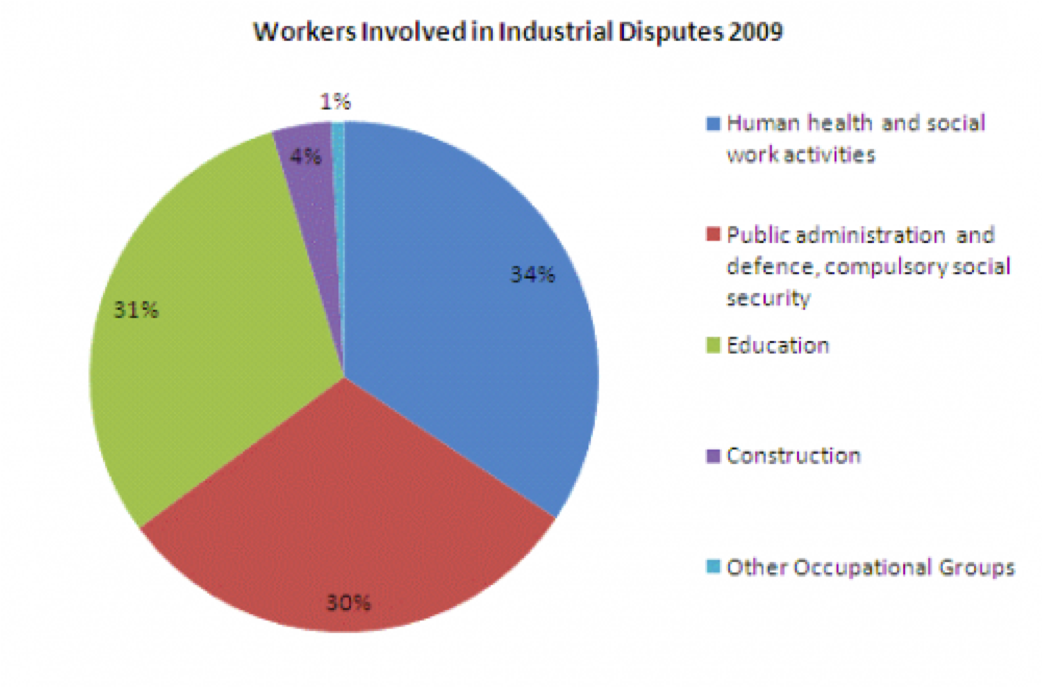

People are already aware of a lot of these things to some degree, but because very little attention gets given to them, their importance can fade from view. In the piece I wrote for the May Day International project, I looked at the sectors of the economy that had shown the greatest militancy, simply in terms of actually having engaged in industrial disputes, since the current crisis began. This is a fairly crude measure, and it doesn’t say a great deal about how potentially militant other sectors are by comparison, given other potential conditions. However it does tell you which groups have demonstrated a capability to mobilise thus far.

We’re talking mostly here, of course, about workers in the public sector. And these workers have been the main target of a concentrated propaganda campaign, on top of being subjected to pay cuts on a scale scarcely if ever seen in rich countries. As illustrated by Richard Wolff’s tweet here, this is not something IBEC members dreamt up in 2006 on a retreat to Lough Derg.

The whole point of cutting public sector pay has nothing to do with getting value for money - it is to drive down wages in the economy, part of what is known as ‘internal devaluation’; what happens when a government is unable to devalue currency to make its exports more cost competitive. The European Commission document ‘The Economic Adjustment Programme for Ireland’ describes how this works in practice in the Irish situation:

Led by cuts in public sector earnings which started in 2009, private sector nominal wages per employee also adjusted, including by declining hourly wages. By promoting cost competitiveness through an ‘internal devaluation’, these developments enhance medium term growth prospects.

Public sector wages maintain a standard for wages in the rest of the economy. This is because there is a greater concentration of unionisation in the public sector, not because the state is a benevolent paymaster. If you can drive down pay and conditions in the public sector, you reduce the number of people affiliated to a union, union contributions fall, and the amount of resources unions have at their disposal to mount campaigns in protection of worker interests falls too.

When you have public sector redundancies, either you cut the provision of the service that the person was performing, you get someone else within the public sector to do more work (‘reform’), you get the public to pay a private company to provide the service (‘outsourcing’ and/or ’privatisation’), or you get members of the public to do it themselves (‘The Big Society’, ‘Meitheal Mentality’). The social costs of this can be immense for those who have to bear them –usually women- way beyond the reduction in what is being paid by the exchequer. But since the people who must shoulder these costs are often those with the least social and political power, it is relatively easy for a right-wing government, aided and abetted by big business propaganda, to mount a concerted campaign against public sector workers.

The means of doing this are so familiar that we tend to forget about them. The most obvious example is the division of workers into the categories of ‘public sector workers’ and ‘private sector workers’ as though these were two different species of human being that thrived in entirely different working habitats but were somehow doomed to co-exist. The whole point behind this is to mobilise animosity among disaffected and hard pressed workers employed in the private sector, or unemployed workers who would expect to work in a private sector occupation, against public sector workers. Their reflexes are manipulated so that they seek, via the assault on the public sector, to drive down their own wages, working conditions and social provision.

As well as that, the purpose of the propaganda campaign is to efface the basic figure of the ‘worker’ from public discourse. Just as the incumbent Tory government in the UK introduced the ‘Minister for Women and Equalities’, where the plural of ‘equality’ indicated that there was no general matter of equality for the government to attend to, merely a series of particular dispersed scenarios where an equality needed to be enforced, the continuous references to ‘public sector workers’ and ‘private sector workers’ serve to develop the idea that there is no such thing as a worker, in the sense of a wage labourer who must sell her labour power to an owner of capital.

Instead, ‘work’ is just the stuff that everybody does to get on in life. There are no relations of power involved, and sure if you own a mobile telephony company and a series of media outlets, or if you clean toilets for a living, at the end of the day, isn’t either just whatever people have to do to make an honest buck? Class? No such thing these days, unless you’re talking about the villains who run the country –the unions, the government, and the public sector fatcats- against the rest of us. At the risk of exhausting my quota of Eoghan Harris references for the next twenty years, his antics in this regard give a really good cartoon sketch of the type of ideological manipulation that is being engineered, though usually under circumstances a little bit more subtle.

Furthermore, attacks on the public sector – the idea that public sector workers should be subjected to rigorous accountability trials, discipline and the fear of getting fired, when not just arbitrarily fired - offers a cheap sensation of power over others that most private sector workers are unlikely to experience in their own working environments. There is an invitation to identify with the managerialist world-view of industry bosses. What the CEO is to the workforce of his firm, the taxpayer shall be to the people working in the public sector.

It’s important not to confine our thinking about this – the attack on public sector workers - simply within the framework of the current crisis, or within Ireland. Consider this piece by Saree Makdisi, writing about California state workers:

The fixation on the basic benefits offered to state workers in return for years of public service, rather than on the grotesque inequalities that surround us, is problematic not only because it distracts us from core questions that urgently require our collective attention, but also because it embodies the potential victory of a stark and misanthropic way of viewing society – basically the view that there is no society, only individuals who are condemned to a primal competitive struggle against one another. Remember what Thomas Hobbes said about that primal struggle in the state of nature? The only certainty was that life was nasty, brutish and short.

What we are talking about here is, as Makdisi points out, the development of the habit of viewing society in a particular way, and one that fits in with the way the owning class portrays itself and society. This is not only in terms of the idea that those at the top (in these parts, wealthy white men) are there on account of the heroic struggles they have won, but also, more viscerally, in the sense that what is public is bad and what is private is good.

That is, the various characterisations of what public sector workers are, or what the public sector is as a whole, serve to shape perceptions of the public and the private, viz.

Public

Private

Bureaucratic

Streamlined

Lazy

Hard-working

Inefficient

Efficient

Unfit (for purpose)

Agile

Parasitic

Wealth-generating

Archaic

Modern

Bloated

Slimline

Secretive

Open

Fat

Lean

Gluttonous

Hungry

Lethargic

Vigorous

Intransigent

Dynamic

Mandarin

Leader

Drain

Self-reliant

And so on, ad infinitum.

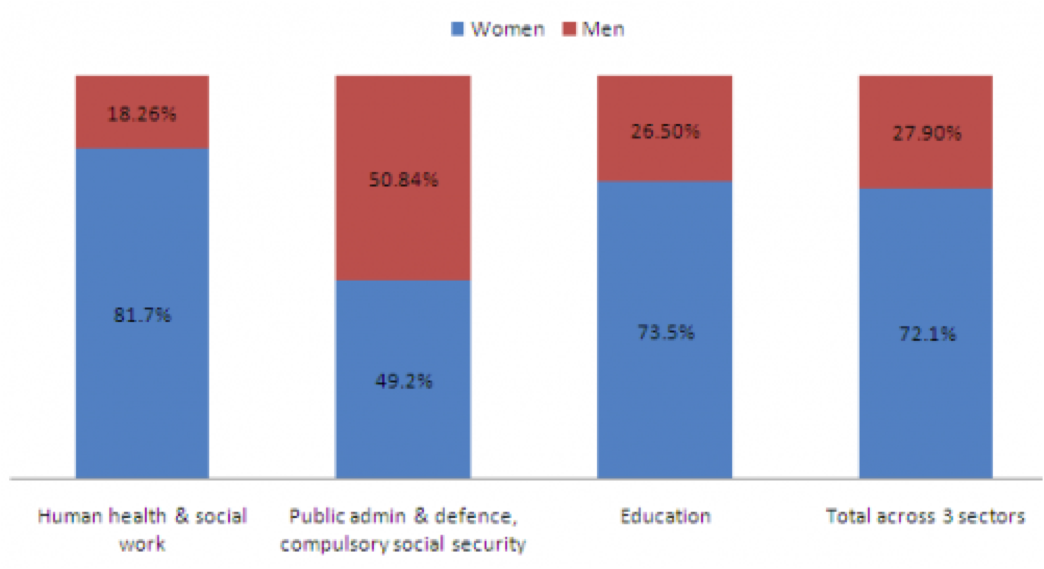

Returning to the question of who is resisting this, and who is under attack. Let’s look at the gender breakdown of the three sectors that have shown the greatest resistance hitherto:

Nearly three quarters of workers in these sectors, habitually demonised as fat, lazy, bloated, inefficient and parasitic, are women.

Nearly three quarters of workers in these sectors, habitually demonised as fat, lazy, bloated, inefficient and parasitic, are women.

Contrast this with the composition of the constituency for whom the EU-IMF-ECB bailout was engineered – the upper echelons of the financial sector. Pauline Conroy’s paper for the TASC conference in 2009 revealed that:

- The Central Bank for 2007 when the banking crisis was dripping into the mainstream was composed of 13 governors of whom 1 was a woman.

- AIB (2006) had a Board of 18 persons, of whom 2 were women.

- Bank of Ireland’s Court (2007) and Non-Executive Directors come to 14 persons, of whom 1 was a woman.

- At the European Central Bank, just one of the six members of the executive board of the governing council is a woman.

Just as public sector pay maintains the standard of wages in the economy, so too do public sector working conditions. We can take this further – pay and conditions for women in the public sector, sustained by protections won by unions- serve to protect pay and conditions for women in the rest of the economy. If the ‘internal devaluation’ program is – like all neoliberal projects - a project for restoration for class power, it’s also a project for the restoration of male power.

Angela Nagle noted on the special Crisisjam edition for International Women’s Day that:

Since the beginning of the recession, Dublin Well Woman Centre has reported an increase in women seeking crisis pregnancy counselling, with one in five citing financial concerns. Chief executive Alison Begas listed among these concerns unemployment, debt and the inability to afford crèche fees. This situation has, unsurprisingly, also been directly linked to an increase in Irish women seeking abortion illegally in the UK. For employed women who have chosen to have children during these turbulent times, UNITE trade union have reported a sharp increase in the abuse of Irish women in the workplace, especially around issues of maternity cover, with pregnant employees being verbally abused and told they would be replaced. For unemployed women who have chosen to have children during these turbulent times, the situation is also grim, with social welfare and child benefit being cut, the cost of education being increased and the chances of remaining in the home and falling permanently into a cycle of poverty rising by the day. Dublin Rape Crisis Centre reported a 42% rise in calls to their now even more under-funded emergency helpline in 2009 and refuges from domestic violence have noted an increase in demand for their services of over 40%. Women’s Aid have found themselves only able to answer one out of two calls because of a lack of resources and 70% of Irish women who reported being victims of domestic abuse cited economic dependence as the reason why they could not leave.

The antiseptic language of the programme of ‘internal devaluation’, which entails ‘getting our competitiveness back’ and ‘developing a leaner, fitter public sector’, is proferred by conclaves of male economists, male industry bosses, male technocrats and implemented by a overwhelmingly male government. We can improve on Makdisi’s description of a ‘stark and misanthropic’ view of society; what we are really talking about is a stark and misogynistic view of society. The class war underway is also, crucially and inseparably, a war on women, and it is women who are both the primary targets, but – as the figures show - also the people who have engaged in the most strenuous public resistance to date. Next time you hear about a bloated public sector that needs to be ‘leaner and more efficient’ or one which exists as ‘the enemy within’, don’t forget to remember who they really have in mind.

Image top Pantagrapher on Flickr.