Raiders of Ethiopia

Some historic manuscripts plundered by the British from Ethiopia in the 19th Century are now in the care of the Chester Beatty Library and Trinity College Dublin. It is time to consider sending them back to their country of origin, say Professor Richard Pankhurst and Dr Elene Negussie

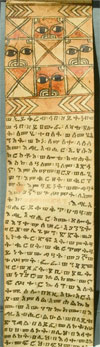

Like the Celtic monks who crafted the Book of Kells, the Ethiopians preserved their Christian tradition through handwritten texts on fine parchment made of animal skin, often embellished with artistic ornamentation. Some of these are to be found in the Chester Beatty Library, Trinity College Dublin and possibly unrecorded in private Irish collections. In Ireland, at least five of the 13 ‘Ethiopic' manuscripts held by Trinity College Dublin, and several manuscripts in the custody of the Chester Beatty Library, can be directly linked to plundering surrounding the British ‘Abyssinian Expedition' and the capture of Maqdala in 1868.

Like the Celtic monks who crafted the Book of Kells, the Ethiopians preserved their Christian tradition through handwritten texts on fine parchment made of animal skin, often embellished with artistic ornamentation. Some of these are to be found in the Chester Beatty Library, Trinity College Dublin and possibly unrecorded in private Irish collections. In Ireland, at least five of the 13 ‘Ethiopic' manuscripts held by Trinity College Dublin, and several manuscripts in the custody of the Chester Beatty Library, can be directly linked to plundering surrounding the British ‘Abyssinian Expedition' and the capture of Maqdala in 1868.

In the case of the Trinity collection, some of the manuscripts were purchased by early-day librarians, either directly from England, or from Dublin-based auctioneers. Others were presented by private individuals such as Colonel Lefroy of Carriglas Manor, Co Longford.

Illicit plundering and theft of cultural heritage are historically widespread features of war. During the Colonial Era, such activities were even considered legitimate by European powers during ‘expeditions' to faraway places, which often included archaeologists and museum personnel who collected ‘exotic' cultural artefacts. Increasingly, the implications of such spoils of war are coming to the fore and claims for restitution are presently under rigorous debate.

A famous and long-drawn case is that of the Elgin Marbles (or the Parthenon sculptures), which were bought by the British government from Lord Elgin, British ambassador to the Sultan of Turkey in Constantinople, for the British Museum in 1816. The Greek authorities are seeking for these to be returned and housed in the New Acropolis Museum in Athens, which is scheduled to open later this year.

In Ethiopia, the capture of Maqdala by the British in 1868 resulted in the removal of a significant portion of Ethiopia's cultural heritage, much of which has now been scattered around the globe. And a small portion of this – mostly historic manuscripts written by priests and monks of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, a cradle of Early Christianity – survives in Ireland.

The Abyssinian Expedition

In 1867, a British expedition was sent to Ethiopia as a result of the detention by Emperor Tewodros (or Theodore) of a handful of British and other Europeans. Under the command of Robert Napier, the king's mountain fortress of Maqdala (or Magdala) was invaded and set on fire. Tewodros himself was defeated in battle, and chose to commit suicide rather than fall into the hands of his enemies. The invading force, as the British historian Clements Markham observed, then “dispersed over the amba”, or mountain top, “in search of plunder”. The treasury was soon “rifled” and, according to Markham, the loot contained “tons” of “manuscript books”.

The troops also broke into Tewodros's principal church, that of Medhane Alem, which was dedicated to the Saviour of the World. Virtually everything in it was taken as booty. The American journalist HM Stanely recalled that the looted articles soon covered “the whole surface of the rocky citadel, the slopes of the hill, and the entire road to the [British] camp two miles off”.

The Looting of Maqdala

The British military authorities, in accordance with the custom of the day, duly collected the loot from the soldier-looters. The goods were then transported, on 15 elephants and 200 mules, to the nearby Dalanta Plain. There a two-day auction was held, on 20 and 21 April 1868, to raise prize money for the troops. “Bidders”, Stanley recalls, were “not scarce” for “every officer and civilian desired some souvenir”, including richly “illuminated bibles” and other manuscripts.

The bulk of the loot – 350 manuscripts – ended up at the British Museum (now the British Library), which thus, according to critics, became a receiver of stolen property. Other manuscripts were acquired by Cambridge University, the Bodleian Library in Oxford, and the John Rylands Library in Manchester. Six of the finest manuscripts were presented to Queen Victoria and are now in the Royal Library in Windsor Castle.

Other important articles of loot ended up elsewhere. Two Ethiopian crowns, a gold chalice and many fine processional crosses were acquired by the then South Kensington Museum (later the Victoria and Albert Museum). After Ethiopia's entry into the League of Nations in 1923, the country's then regent, Ras Tafari Makonnen (the future Emperor Haile Selassie) paid a state visit to Britain. Faced with the need to honour the princely visitor and his then imperial ruler Empress Zawditu, the British foreign office decided to return one of the two crowns. The gilt crown was given back to Ethiopia in 1925, while the crown of solid gold was retained in London.

The Quest for Restitution

Extensive coverage of the issue of looting in the Ethiopian and international press led to the foundation of AFROMET, the Association for the Return of Maqdala Ethiopian Treasures. The agitation of the association – which has branches in both Ethiopia and Britain, and enjoys the support of the Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone – has resulted in the repatriation of an increasing number of articles from Maqdala. Most notable of these was the Royal Amulet which Emperor Tewodros was wearing at the time of his historic suicide: an artefact which can be seen at the Institute of Ethiopian Studies Museum, and has been featured on an Ethiopian postage stamp.

The issue has been recognised internationally and UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, has played a key role in the restitution debate. Its 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property provided a useful mechanism for restitution, although it cannot be applied retroactively. The Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its Countries of Origin or its Restitution in Case of Illicit Appropriation has provided a better framework for bi-lateral negotiation for restitution of cultural property lost due to foreign or colonial occupation prior to 1970. Although no enforcement measures exist, this is the “age of evolving moralities” in the words of the British archaeologist Colin Renfrew.

The ICOM Code of Ethics for Museums, 2006, by the International Council of Museums, stipulated that museums and cultural organisations should explore the possibility of developing partnerships with museums in countries that have lost a significant part of their heritage.

Measures to be Taken

So what of items like this in Ireland? The first step to be taken is to achieve immediate scholarly access to Ethiopian manuscripts in Ethiopia. It is estimated that at least 5,000 Ethiopian manuscripts are scattered in Europe, North America, Asia, and Oceania. Whereas microfilming in Ethiopia has been of major assistance to international scholarship, the failure to copy Ethiopian manuscripts in the rest of the world remains an obstacle to scholarship within Ethiopia itself.

Written in Ge'ez – an ancient language still used in the liturgy of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church – the manuscripts are of little use to scholars outside Ethiopia. They are, however, essential for the study of Ethiopia's history and culture. The majority of the manuscripts are religious, but many are devoted to secular subjects such as law, government – including royal chronicles – mathematics, medicine and linguistics. They are also of great significance for studies in Ethiopian art.

The Chester Beatty Library acted on this matter by handing over microfilm copies to the Ethiopian prime minister on a state visit to Ireland in 2002. Elsewhere, the likes of Yale University in the United States and Uppsala University in Sweden have provided microfilm of all manuscripts in their custody directly to the Institute of Ethiopian Studies in Addis Ababa. Trinity College Dublin should follow this example by initiating a digital photograph project.

The second step is to consider whether some of the manuscripts in Ireland – those that carry the stigma of loot – should be returned. A committee needs to be established representing both Ethiopian and Irish cultural interests in order to work out both short- and long-term plans in partnership.

Perhaps a partnership project could be established between Trinity College Dublin, the Chester Beatty Library and the Institute of Ethiopian Studies.š

Professor Richard Pankhurst is founder of the Institute of Ethiopian Studies. Dr Elene Negussie is lecturer on the World Heritage Management Programme at UCD