Primal words

John Lennon's legacy is elusive, but Harry Browne says the 25th anniversary of his murder was followed by an event that helps put the Beatle in perspective: the death of his contemporary and fellow tortured-genius, Richard Pryor.

Sure, the bigger-than-Jesus band known as the Fab Four was more than the sum of its parts, and its parts were all essential and variously great. Nonetheless, I've always felt something akin to pity for people whose Favourite Beatle is not John Lennon. Do they not realise what a terrible confession of intellectual inadequacy and emotional shallowness they're making?

I can make an exception for the rare Ringo-lover, whose preference expresses an admirable, rather John-like love of insignificant clowning. But those who favour George and, especially, Paul declare their partiality for lyrical banality and sweet tunes over the bare-faced complexity of an angry, funny, revelatory genius who shakes, rattles and rolls our souls to their foundations.

Or something like that. Actually, as the 25th anniversary of his murder came and went, and each pro forma media tribute felt less adequate than the last, it became apparent that John's precise appeal is hard to pin down, for me as much as for the (other) inadequate tribute-payers. His outbursts of creativity include "Help!" and "Norwegian Wood", "All You Need is Love" and "I Am the Walrus", "Come Together" and "I'm So Tired", "Working Class Hero" and "Imagine" – he's hard to equal, and hard to get.

And yet he was so articulate about himself. The closest any anniversary-tribute came to opening up the mystery of John was a piece on the Counterpunch website (http://www.counterpunch.org/lennon12082005.html): it's a 6,000-word interview conducted by Tariq Ali and Robin Blackburn for a Trotskyist magazine, The Red Mole, in 1971. At this time Lennon was deeply immersed in what reads like a therapeutic form of Marxism – primal screams against capitalism, if you like. His long reflections on class consciousness put the emphasis squarely on the consciousness.

Pop-culture being a strange beast, the results are still audible in this month's Christmas muzak: "War is over, if you want it" goes the chorus at the end of "Happy Christmas (War is Over)" – and with most people's consciousness circa 2005 it seems remarkably easy to ignore the message.

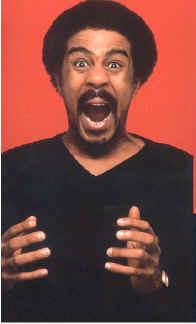

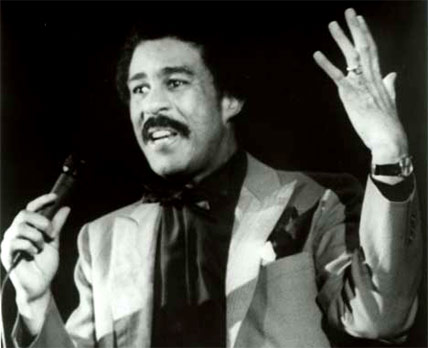

A few commentators tried to squeeze some significance out of the fact that George Best, sometimes called the Fifth Beatle, died a fortnight before the anniversary of his fellow Sixties icon. But 10 December saw the death of another wayward genius who had much more in common with Lennon: Richard Pryor.

The great African-American comedian had a throwaway line that was the comic equivalent of John and Yoko's "bed-in" for peace. "Gettin' some pussy beats havin' a war," Pryor said.

But the commonalities go further than a preference for sex over militarism – which is, after all, shared if not so cogently expressed by most sane people. Pryor was born a few weeks after Lennon in late 1940. And he very nearly died a few months before Lennon's murder in 1980: Pryor was severely burned when, apparently, he was "freebasing" cocaine. (He made brilliant comedy out of the incident, but his career never fully recovered.)

In between, both men spent most of the sixties enjoying what they came to see as stifling success: Pryor was no Beatle, but a tuxedo-wearing Vegas-type stand-up. Like Lennon, Pryor broke free thanks to a combination of drugs and exposure to the avant-garde artistic and political counterculture, prompting him to work that mercilessly exposed his inner life and the external forces that had oppressed him.

"He documented every pain, every abuse that he suffered in his life." Lenny Henry's comment last week about Richard Pryor could also apply to some of John Lennon's solo records. The big difference is that Pryor made his pain, and his people's suffering, incredibly and startlingly funny, achieving unprecedented commercial success. John's solo career, though often brilliant, included a large share of errors, mediocrities and unwise collaborations, and was treated as a Beatles-afterthought by mainstream culture.

"He documented every pain, every abuse that he suffered in his life." Lenny Henry's comment last week about Richard Pryor could also apply to some of John Lennon's solo records. The big difference is that Pryor made his pain, and his people's suffering, incredibly and startlingly funny, achieving unprecedented commercial success. John's solo career, though often brilliant, included a large share of errors, mediocrities and unwise collaborations, and was treated as a Beatles-afterthought by mainstream culture.

The two men were the towering cultural icons of my youth in New Jersey in the seventies, but in my black neighbourhood it was each new Pryor album that generated buzz and excitement and a sense of danger (especially if our parents heard it). Lennon slipped into domestic retirement on New York's Upper West Side, and his status was based largely on the fascinating genius of his Beatles-era persona.

His retirement companion, Yoko Ono, remains a contentious figure for John's fans. Reading the Red Mole interview, in which she takes part, it's clear that she likes the therapy-speak, encourages John's burgeoning feminism – "Woman is the Nigger of the World" was written around this time – but is not so fluent in the passionate jargon of Marxism. Her own political and charitable activities since John's death have been mostly admirable but can be described as liberal rather than radical. (Her artistic work has raised more hackles, including the images of a woman's breast and a woman's pudendum that bedecked Liverpool during last year's Biennial there. She called the work "my mummy was beautiful" and said it was a tribute to John's mother Julia.)

Yoko, however, should require no excuses. Her reputation as an artist pre-dates her relationship with John and survives it. And while John's last, Yoko-soaked album of married contentment, Double Fantasy, didn't do a lot for an alienated teenage punk in New Jersey, surely there was and is some comfort in hearing that our complicated, once-tortured hero felt happy at home.

Anyway, Double Fantasy carries such terminal significance only because on 8 December 1980, when John and Yoko came home to their apartment building, Mark David Chapman intervened. The album became, by terrible necessity, John Lennon's last major artistic statement, but the final word on his life remains extraordinarily elusive.