Poverty in Ireland

One million people in the Republic of Ireland live in poverty. Poverty is endemic to Irish society and extends not just to the unemployed, the travellers, and the slum-dwellers, but reaches right into the middle classes.In Ireland, social inequality is greater than in any other EEC country. The proportion of total income which goes to the poorest 30% is smaller here than elsewhere in the EEC, while the richest 30% here get a higher proportion of total income than the EEC average. The 300,000 at the top of the pile receive six times the income which goes to the 500,000 at the bottom.

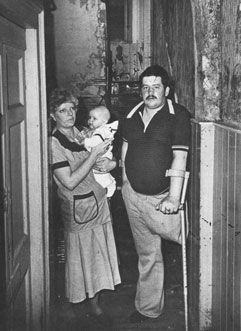

Up to one million people living in the 26 Counties face a constant struggle to provide themselves with the basic necessities of food, accommodation and clothing. They llre debarred from many experiences which the majority of the population take for granted: holidays, entertainment and home comforts. Their expectations are low; they can have little hope of escape from their social ghetto, and even less of a chance to participate in political life and begin to do away with the ghetto.

Few recognise these large numbers at the bottom of the social pile as living in poverty. The fairly recent memories of children without shoes, of widespread insanitary housing and of malnutrition define for many what it is to be poor. The last twenty years of accelerated economic development have dulled sensibilities to the inequities which have survived that process. Nearly one million people do not have access to services and resources which most accept as part of their normal life-style and environment. 400,000 depend on state benefits which they only receive after a means test has demonstrated that they need welfare support. A total of nearly 800,000 of whom over one third are children, are exclusively or largely dependent on weekly social welfare or health board payments. The average weekly income of £30 which the social welfare dependants "enjoy" is, in anybody's book, very low. But the state services and official bodies have recognised that poverty and the need for income support stretch to nearly twice that amount for the average household, Le. just below £60 for a couple with two children.

Few recognise these large numbers at the bottom of the social pile as living in poverty. The fairly recent memories of children without shoes, of widespread insanitary housing and of malnutrition define for many what it is to be poor. The last twenty years of accelerated economic development have dulled sensibilities to the inequities which have survived that process. Nearly one million people do not have access to services and resources which most accept as part of their normal life-style and environment. 400,000 depend on state benefits which they only receive after a means test has demonstrated that they need welfare support. A total of nearly 800,000 of whom over one third are children, are exclusively or largely dependent on weekly social welfare or health board payments. The average weekly income of £30 which the social welfare dependants "enjoy" is, in anybody's book, very low. But the state services and official bodies have recognised that poverty and the need for income support stretch to nearly twice that amount for the average household, Le. just below £60 for a couple with two children.

About 40 per cent of the population, or 1 ¼ million, are covered by medical cards for doctors' and chemists' fees. As of January 1980, the income limit for a couple and two children is £57 - before expenses on housing are considered.

The committee reporting to the Minister for Justice on civil legal aid and advice, and chaired by Justice Denis Pringle, reckoned that the same proportion of the population would be able to contribute "very little, if anything at all" towards the costs of such legal services. They suggested a threshold of £45 per week for a couple and two children in 1977, which is equivalent to about £56 per week at today's prices.

Up to that same threshold state benefits and taxes give households more in their hand as spending power than does their initial cash income, usually wages. The redistribution of income effected through taxation and transfers gives people a disposable income which is higher than their direct income when this is two thirds of the average, or less, is below £60.

Above that limit, taxation and transfers tab away from their purchasing power. However, the increase effected by state benefits is marginal - less than 10 per cent on average for households around the poverty line and certainly not enough to take them out of poverty. These calculations do not take account of the impact of state spending on education which tilts the balance of it.

This, then, can be set as a welfare or poverty line: two thirch of the average income. The state recognises it in several formal and informal ways. Applied to household incomes or to personal incomes, that limit shows consistently one third of the population below it. But these are not evenly distributed throughout the country as the slight drop in the proportion of rural households with incomes less than two thirds of the national average is about 40 per cent while that of urban households is below 30 per cent.

Peter Townsend, Britain's leading poverty researcher and author of a recent mammoth work on the subject, has suggested that people with less than half the average income are in poverty and that those between one half and four fifths are on the margins of poverty and likely to move in and out of the lower category. The two-thirds of-average limit which emerges from an analysis of Irish household incomes falls neatly into the middle of Townsend's margin band.

Peter Townsend, Britain's leading poverty researcher and author of a recent mammoth work on the subject, has suggested that people with less than half the average income are in poverty and that those between one half and four fifths are on the margins of poverty and likely to move in and out of the lower category. The two-thirds of-average limit which emerges from an analysis of Irish household incomes falls neatly into the middle of Townsend's margin band.

The people who have incomes equivalent to two thirds of the national average or less are a much more sizeable but less easily identified group than the travellers, slum-dwel. lers, old people living alone, or struggling small-farm families on the Western seaboard who are most commonly associated with the notion of poverty. They reach into the new suburbs, even into the middle class.

The one million people whose incomes come comfortably inside the two-thirds-of-average limit don't all have particular problems of old age, unemployment, single parent. hood, although poverty for someone with any or all of those conditions is almost inescapable. Nearly half of the poorest 30 per cent of households are families with dependent children and in just less than half of those, one of the parents is working. The size of the family and the size of the pay-packet weigh very heavily in the balance of circumstances which lead to poverty.

For families with children, the chances of falling into poverty increase as the cost of providing for the children increases, that is, as they get older, but before they bring in another income. For single people, the chances of falling into poverty increase with age above 55.

Single women are much more likely to be poor than single men, whether they are deserted or separated wives struggling to provide for children on state benefits, or unmarried working and suffering the still effective discrimination of unequal pay. Approximately equal numbers of single men and single women were assessed for income tax in the last year for which details are available (1977); the average income of the women was three quarters the average for men. Women outnumber men by a large margin in the one million people who live in poverty. The margin is 3: I in the very poorest 100,000 of those.

Less than half of the total number of people drawing unemployment benefit or unemployment assistance come into the poorest 30 per cent of households as do less than half of those receiving state pensions. But a very slight movement of the income threshold upwards would probably show the bulk of these clustered just over the margin. The additional incomes from supplementary allowances, part· time work, other members of the family, or pensions from former employment put them outside the chosen statistical bracket - but not necessarily outside the ranks of the poor.

The linkages between old age and poverty, and between unemployment and poverty are very strong, but they are not nearly exclusive. A quarter of those who qualify for medical cards are wage-earners. One fifth of the poorest 30 per cent of households include children and one wage earner. Nearly one third of the poorest 30 per cent of households include neither children nor elderly people.

The poorest 30 per cent in the 26 Counties have a smaller share of total national income than do the poorest 30 per cent in most Western European countries. So, not only is the income per head of the population smaller than in all the EEC member states but the proportion of total income going to the poorest is smaller, too. At the other end of the scale, in the richest 30 per cent, the proportionate slice going to that group in the 26 Counties is above the Western European average.

The poorest one third of households in the state receive one ninth of total income; the poorest half receive less than one quarter of the total, that is, less than the cut taken by the richest ten per cent. The 350,000 at the top of the pile receive six times the income which goes to the 500,000 at the bottom.

All the indications are that the inequities are increasing. The experience of the recession of the mid-1970s shows that it is the poorest who recede first. There has been a barely perceptible move towards greater equality for the tcn years up'to that, but the trend was reversed in the following two years. The weaker sections of the population bore the burden of the recession not only through unemployment but also in a shift of income to the higher income-earners.

All the indications are that the inequities are increasing. The experience of the recession of the mid-1970s shows that it is the poorest who recede first. There has been a barely perceptible move towards greater equality for the tcn years up'to that, but the trend was reversed in the following two years. The weaker sections of the population bore the burden of the recession not only through unemployment but also in a shift of income to the higher income-earners.

Economists working in the social welfare field believe that the gap has continued to widen, that access to income, to education and to housing is increasingly difficult for the poorest and weakest. Only in health provisions is the gap between rich and poor closing.

There is some redistribution of income through direct taxation, differentiated rates of indirect tax, social welfare payments and state support for education, health and housing. But it is weak - and significantly weaker through taxation than through such benefits as pensions and children's allowances. Yet the spending on social welfare is a declining proportion of overall government spending, falling from 16 per cent in 1975, to 13 per cent in 1979.

It is doubtful, at best, that the diversion of state funds from 1977 to 1979 into job creation schemes intended to alleviate poverty through the elimination of unemployment redressed the balance.

The real value of social welfare benefits has gone up by about 2h per cent~nn ally for the past five years - a smaller increase than that of industrial earnings. However, the real value of children's allowances has declined and in spite of the recognition that larger numbers of children and older children impose particular burdens on families, no specific provision is made to meet this need. The level of payment per child is stable from the second child upwards.

The value of the monthly allowance for the first child (at May 1978 prices) dropped from £3.95 in 1974 to £2.30 in 1978, with similar losses in the value of allowances for the second and subsequent children. Again at May 1978 prices, the total payment to a family with four children fell from £35.46 in 1974 to £25.80 in 1978. And the value of the income tax allowance for children has fallen at the same time.

While the February Budget deliberately cut the tax allowance it did set out to increase the allowances but the real value of the allowance for the first child is still 50 pence below the 1974 level and the drop in the real value of total allowances for a family of four children is over 40 per cent, even with the increases due in July. Children's allowances in the 26 Counties are lower than the corresponding payments in any other EEC member state when different wage levels are taken into account.

There are 68,000 people receiving disability benefit at a new maximum rate, for a person with two children and dependant spouse, of £45.60 per week. 62,000 receive oldage contributory pension at a new maximum (from this month) of £44.55, if they are aged 80 and they have an adult dependant over 66.

Unemployment assistance for a person with an adult dependant and two children ts paid at a maximum of £39.85. The widows' non-contributory pension, paid to 65,000 people, comes to £22.50 for a person under 80 with no dependants. Among the 400,000 who rely almost entire-' lyon social welfare payments, the biggest single group is the 134,000 elderly people receiving non-contributory pensions, for which the maximum payment with one adult dependant is £31.55 a week. The £7 and £8 increases which take effect this month for pensioner couples and married men with children who are on unemployment assistance will still leave the vast majority of them comfortably (or uncomfortably) inside the poverty line.

There are few opportunities for supplementing the in. come from benefit.s subject to a means test. The "income disregard" limit - that is, the amount which may be earned in part-time work, out-work at home, or by other meansstands at a mere £6.00. Many of the women who do night cleaning, or work at home knitting or punching cards, are deserted wives, unmarried mothers or the wives of the long term unemployed. They have to disguise the income they receive from these sources in order not to lose the full value of benefits and allowances. But the work is still necessary in order to makes ends meet.

The "poverty trap" can catch a deserted wife for no more shameful reason than that the maintenance she reo ceives from her husband increases. By giving her an income above the means-test limit and thus reducing her allowance, the increased maintenance may result in a net loss of income.

A round of means tests and follow-up inspections is just part of the humiliation of poverty. There are means tests for a range of state benefits, for medical cards, local authority house loans and rent subsidies. But the "passport principle" of making qualification for one benefit or service auto· matic qualification for another is applied only in a limited range of cases. And the means tests have not yet been standardised.

Behind the means test lies an assumption which reflects the historical period and political circumstances of its introduction, that people own the house they live in. Housing expenses are not recognised in the means test for assistance payments. These expenses are especially severe for those in private rented accommodation in towns and cities who may make up one fifth of social welfare recip· ients in some categories.

Behind the means test lies an assumption which reflects the historical period and political circumstances of its introduction, that people own the house they live in. Housing expenses are not recognised in the means test for assistance payments. These expenses are especially severe for those in private rented accommodation in towns and cities who may make up one fifth of social welfare recip· ients in some categories.

The recently increased pressures on public housing come at a time when the state's financial commitment to it is declining in value. It reflects the exclusion of an increased proportion of the population from the market for specu· latively built private houses and ensures that housing will remain a central determining factor of poverty.

Poverty is endemic in the society of the 26 Counties. It is not just the experience of marginal groups which can be ended by a series of regulations and benefits. The unemployed are concentrated in the ranks of the poor but they take their place there alongside even larger numbers who are employed.

Poverty is the fate of tens of thousands of elderly people who can "look forward" to poverty as a near-certain part of retirement particularly if they live alone. Nearly half of those of pension age qualify for means-tested benefits. The average age of heads of the poorest 15 per cent of house. holds is 62.

Poverty reflects the very marked inequality in this society, an inequality which two decades of rapid economic development have done little or nothing to reduce. The rising tide has not lifted all boats by the same margin. The life chances for the poorest one third have not broadened at the same rate as those for the majority of the population. In that sense, the poor will always be with us, because this society constantly reproduces the structures which keeps them poor

LOW WAGES

The lowest-paid are also the slowest to advance. The 28,000 who work in the six industries producing the lowest hourly and weekly earnings have had smaller increases since the 195 Os than those in all other industries. Their "progress" is, in some cases, less than half that of those on top earnings.

In these six categories - hosiery, boots and shoes, clothing, textile goods, furniture, and leather - the hourly earnings range between 55 and 65 per cent of the average for all manufacturing industries. The average hours worked are shorter, too - just over 38 as compared with an overall average of 42. Both the low pay and the shorter hours reflect the concentration of women in these industries, where there is an above-average amount of part-time work.

70,000 workers, including 30,000 farm labourers, have minimum wage rates set by Joint Labour Committees (JLe's) whose regulations have statutory power. Outside of agriculture, women are again disproportionately represented. The 18 JLC's cover a range of services and industries with weak trade union organisation and generally fairly small work-forces.

70,000 workers, including 30,000 farm labourers, have minimum wage rates set by Joint Labour Committees (JLe's) whose regulations have statutory power. Outside of agriculture, women are again disproportionately represented. The 18 JLC's cover a range of services and industries with weak trade union organisation and generally fairly small work-forces.

The services (for which no statistics on earnings are available) include hotels, catering, hairdressing and clerical work in solicitors' offices. The minimum weekly wages for adults go from £45 to £60. In most of the categories there would be few opportunities to boost earnings through productivity schemes and overtime. So, the bulk of these 70,000 take home less than half the average male industrial earnings.

Since the collection of data on distribution of earnings ceased ten years ago it has not been possible to assess the claims made for National Wage Agreements (introduced in 1970) that they have protected the lower-paid. But by 1978, even the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union which has supported all but three proposed National Agreements (and then always accepted the barely revised versions) had its doubts and it launched the HELP (Higher Earnings For LowerPaid) campaign, focussing attention on workers whose basic wage was £50 or less.

The campaign encouraged negotiators to seek preferential treatment for the low-paid, using the limited flexibility of the 1978-79 National Wage Agreement. But where progress was held up by recalcitrant employers who were little impressed with the union's HELP campaign, the loopholes were closed by the National Understanding of last year. The Union has no detailed record of the campaign's results but it is known to have improved the position of a couple of thousand workers in jobs where all were low-paid, even if it did not do much to narrow differentials within particular employments.

The stumbling block of differentials was one of those on which the Irish Congress of Trade Unions' committee on low-paid workers fell three years ago. It is now being revived, reflecting a greater concern with the problems of low pay. A more dramatic turn in the same direction was taken last year when the ICTU reversed its policy of a few years previously and called for a national minimum wage. However, neither the level of that base-line nor the means to achieve it have been agreed.

Those industries most vulnerable to intensified competition and who felt the mfst severe effects of the mid 1970s recession are also those with below wage rates. It was they who were most likely to claim "inability to pay" under clauses of the National Wage Agreements recognising "special economic circumstances". At the other end of the scale, well organised workers in industries showing steady growth were able to circumvent the National Agreements and boost increases on the basic wage through productivity bargaining and incentive bonus schemes.

The first and only study of the impact of National Wage Agreements has been prepared for the Economic and Social Research Institute by Jim O'Brien, now with the Dublin Newspapers Management Committee. It is unlikely to provide much comfort for those who advocate National Wage Agreements as a means to protect the low-paid when it is published later this year - just in time for the next round of centralised pay bargaining.

The impact of low pay is very evident from the results of the 1977 Household Budget Survey published late last year. For households with incomes between £30 and £60 (£37.50 and £75 at late 1979 prices), wages formed the bulk of income - from 55 per cent at the lower end of the bracket to 80 per cent at the higher end. The worker with a family to support on a wage of less than £60 per week is one of the categories of poor which the state supports cannot adequately assist and which voluntary agencies such as the Society of St. Vincent de Paul encounter even more frequently.

ON THE DOLE

However persistent the myths of dole scroungers and of unemployed persons earning more than those at work may be, the fact is that 87 per cent of families with children and with neither parent working find themselves in the poorest 30 per cent of households. 100,000 children are dependants of unemployment assistance recipien ts. The maximum weekly payment to a long-term unemployed person with an adult dependant and two children is £39.85. And more than one third of unemployed men have an adult dependant and at least two children.

A recently published report on unemployment in the Dublin suburb of Ballyfermot shows the concentration of people without work in particular areas of multiple deprivation. 16 per cent of the labour force in Ballyfermot is out of work - twice the national average. The levels of unemployment are higher again among teenagers and in the 45 to 64 age group who generally become "unemployable" after being made redundant. Among teenagers, unemployment is 17 per cent higher than the national average; in the older age group it is 81 per cent higher.

Previous reports have demonstrated the same accumulation of unemployment, low pay and low participation in higher education in older working class areas. Surveys of Southill (Limerick) and Edenmore (North Dublin) showed that anything up to one quarter of adult males were unemployed. The Edenmore survey, carried out by the local branch of the Socialist Labour, Party, shows that 29 per cent of those between 16 and 19 were unemployed. However, young people do not become eligible for unemployment benefit until the age of 18. So, in an area like this the increased costs of providing for older children are felt especially keenly.

Previous reports have demonstrated the same accumulation of unemployment, low pay and low participation in higher education in older working class areas. Surveys of Southill (Limerick) and Edenmore (North Dublin) showed that anything up to one quarter of adult males were unemployed. The Edenmore survey, carried out by the local branch of the Socialist Labour, Party, shows that 29 per cent of those between 16 and 19 were unemployed. However, young people do not become eligible for unemployment benefit until the age of 18. So, in an area like this the increased costs of providing for older children are felt especially keenly.

In the north inner city of Dublin a November 1978 study showed that half of the unemployed were receiving the minimum benefit. In five out of the seven streets or blocks with unemployment levels even above the 18 per cent recorded for the area as a whole, three quarters received only the means-tested assistance. Over half of the unemployed were registered as unskilled. At work, they would command the lower rates of pay and would have little chance of saving for the "rainy day" - that is, for the unemployment which comes as an inevitable part of their life-cycle. Thus, a lack of skills or even the possession of skills which are only appropriate to a declining industry, low pay and unemployment are links in a vicious circle of poverty.

Studies of the unemployed on the Live Register in late 1977 and late 1978 showed that the proportion who were long-term unemployed was increasing, including the section who have ceased to qualify for any state benefit at all. The average income of the unemployed was seen to be a declining proportion of the earnings of those at work.

The proportion of the unemployed who are claiming the higher unemployment benefit rather than long-term assistance is declining. In 1975, the ratio of benefit claimants to assistance claimants was 3:2; in 1978 that ratio was 1:1. The percentage of male unemployed who have been out of work for more than six months has gone up one or two points each year from a level of 50 per cent in 1976. The average number of weeks worked during the previous twelve months by those on the Live Register has dropped steadily in the same period, while the percentage of claimants with no work experience at all has gone up.

So, while the total number of unemployed (as recorded on the Live Register) has fallen, the position of those on the dole has worsened steadily and, in spite of improvements in maximum payments of benefit and assistance, the gap between them and those at work has widened.

The Live Register is widely recognised to be an inaccurate measure of the extent of unemployment and gives no impression at all of under· employment. The figures do not nor· mally include those who have left school and are looking for work but who have not yet found a job. Some of these would, indeed, be eligible to "sign on" but because they are living at home are entitled to such small payments that the journey to the labour exchange is not worthwhile. The 1977 Labour Force Survey, estimated that 15,000 people over the age of fifteen were looking for their first job.

The Live Register does not record as unemployed the many women who have been refused assistance despite their claims to be seeking work because they are considered to have home duties which make them unavailable. Changes in pension entitlements and in the upper age limits for some benefits have removed many more from the Live Register who are still fit for, and in search of, work. Most recently, seasonal adjustment of the figures to take account of regular fluctuations through the year have reduced the number on the Live Register. Also, the reduction to negligible amounts of workers on shorttime has contributed to the overall decline in numbers on the Live Register since 1975, when short-time workers reached over 9,000.

STATISTICAL GAP

The possibility of the government and of state agencies tackling poverty hinges largely on the precise information they have as to who is poor and why. But the available information on the distribution of income in the 26 Counties is anything but precise.

By the time the results of research on the redistributive effects of taxes and benefits carried out by a Central Statistics Office team were published quietly two days before the Budget they were out of date. The basic material on which the more sophisticated calculations were done was collected for the 1973 Household Budget Survey, that is, before the mid-1970s recession which opened up the gap between rich and poor.

However, that CSO study is one of the very few from a state body to deal with income distribution. When economist Brian Nolan, then with the Central Bank, published a paper on the same subject, and using some of the material, two years ago, it was greeted as "light in a dark area" and 'pioneering work' by fellow-economists and statisticians.

However, that CSO study is one of the very few from a state body to deal with income distribution. When economist Brian Nolan, then with the Central Bank, published a paper on the same subject, and using some of the material, two years ago, it was greeted as "light in a dark area" and 'pioneering work' by fellow-economists and statisticians.

Nolan himself underlined the connection with poverty: 'I would like to reiterate the importance of relating research on income distribution to the problems of poverty and need ... the relevance here of the study of redistribution in particular is obvious.' He pointed to the weaknesses of the income data contained in the Household Budget Survey; as they are based on voluntary statements they are likely to under-estimate the real levels, a presumption confirmed by the discrepancies between income data and expenditure data.

For over ten years, governments and state bodies have recognised the inadequacy of their statistics relating to poverty. The Third Programme for Economic and Social Development (1969) referred to the 'need for more information regarding the distribution of incomes.' Yet it was in that same year that the Central Statistics Office ceased compiling its series on the distribution of earnings. In justification for this move, the CSO has variously cited lack of demand and the unreliability of the statistics.

The National Economic and Social Council and the Economic and Social Research Institute, both funded by the state, repeat the demand frequently for more statistical information of this kind. In 1975, the NESC stated that it was 'a matter of urgency to assemble the statistics that would give a comprehensive picture of income distribution in this country.' And a year later, the NESC suggested that 'some blame for the low level of debate on social issues must rest on the inaccessibility of some of the relevant information.' And they drew up a comprehensive list of recommendations to government departments on the reports they should publish.

The ESRI's plea is little different. In a 1974 report, it was stated: 'Unfortunately in this country, as in most others, statistics of income distributioll by size are the least developed, though obviously most important from the social point of view; without them how can the problem of poverty be properly investigated?'

The passing reference to other countries is misleading, however. Economist Patrick Lyons who published a study of the distribution of wealth in 1972 has said that Ireland is 'unique among developed nations (in that) we have no information about the distribution of incomes.' In Britain much of the information which it would take months of computer work to assemble here, if the raw material exists at all, can he bought in a well presented statistical summary, 'Social Trends', over the counter.

Few of the NESC recommendations have been acted on but there has been a slight improvement in the quality of statistics on income, both through the greater detail of the Household Budget Survey (research work on whose 1980 edition is just beginning) and the publication of annual reports by the Revenue Commissioners. However, the time it takes to publish them diminishes their value. The 1977 report of the Revenue Commissioners was publishcd in mid-1979.

The NESC insists that 'the aim of the public service, and of Ministers too, should be to promote understanding of the issues involved, so that the public are aware of the extent of various social problems and can seriously and realistically discuss alternative strategies to resolve them.'

There is no indication that the civil service or the government accept that. Objections from the Department of the Environment have prevented publication of a report commissioned by An Foras Forbartha on the condition of the country's housing stock. The small bits that did filter out caused panic - in state offices.

A report on income support services commissioned by NESC from Eithne Fitzgerald was delivered to the government at the end of October, printed and bound. Four months later, it was still unpublished - and likely to remain so until the Budget controversy had died down, for the report implies very specific recommendations as to what that Budget might have done to redress the loss in real value of state transfers to families with children.

SINGLE PARENT FAMILIES

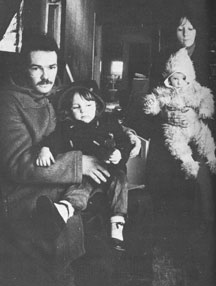

Those social groups which are traditionally denied direct access to earned income are those most likely to experience poverty. Apart from the old and the disabled, the most obvious examples are women and children who are supported by a husband or father. When that support is cut off, as in the case of the widowed, separated or unmarried mother, the threat of poverty increases dramatically.

In Britain, one in ten families is headed by a lone parent. Almost half these families and two fifths of the children of these families live in or on the margins of poverty. Most of these families are headed by women. Of these women, the widowed and the divorced fare best. Separated women and unmarried mothers are worst off.

In Ireland, there are no recent statistics on one-parent families. According to the 1971 census, there were over 80,000 families with one parent and at least one child. More than two thirds were headed by women. There is every reason to believe that the number of single parent families has increased since 1971, especially those with young children. Separations are on the increase and more single mothers are choosing to keep their children.

In Ireland, there are no recent statistics on one-parent families. According to the 1971 census, there were over 80,000 families with one parent and at least one child. More than two thirds were headed by women. There is every reason to believe that the number of single parent families has increased since 1971, especially those with young children. Separations are on the increase and more single mothers are choosing to keep their children.

The absence of divorce legislation and the exorbitant cost of legal separation proceedings results in broken marriages being concluded either in orders for maintenance payments or in desertion. Dublin District Court handles about 400 maintenance payment orders each year, a figure which has levelled off in recent years following the mid-1970s boom in marital breakdown.

Desertion - sometimes called the poor man's divorce - among Dublin couples occurs most often among the lower income groups. The average age for desertion is about 30 and there are usually three to four young children involved.

More than 5,000 women collect either deserted wives' benefit or the means tested allowance. For a mother with three children the weekly rate is £41.70 for the allowance and £45 for benefit. Most of these women are worse off now than they were when their husbands supported them, although even then they were at the lower end of the income scale.

About 4,000 women collect the means tested unmarried mothers allowance of £27.90 for a woman with one child. Their major problem is accommodation. Most are in private accommodation which often eats up half their weekly income or more. Not only is accommodation expensive, it is insecure because of the social stigma which still surrounds the unmarried mother. Many are forced to move as often as four times in the first year of their baby's life. Hostel accommodation is severely limited and by the time most unmarried mothers get local authority housing (if they succeed at all) their babies are usually several years old.

Because of the housing problems, unmarried mothers are one group who clearly can not live on the state stipend. If they work, or have any other source of income, anything they make over £6.00 per week will be deducted from their allowance.

Two studies in progress at the moment indicate that most unmarried mothers must return to work as soon as possible because the allowance is so inadequate. Until they sort out their accommodation and child care problems, many seek "off the record" jobs that won't interfere with social welfare payments. There is no shortage of employers who are willing to offer low-paid, uninsured jobs to desperate people.

However inadequate the unmarried mother's allowance is for a woman and her baby it is far more inadequate for a woman and a growing child. Social welfare payments for child dependants are the same for a two-month-old baby as they are for a ten-year-old child (although the child dependants of some categories of social welfare dependants receive more than the child dependants of others).

The realities of dealing with a growing child and inadequate allowances mean that unwed mothers do not really benefit from the constitution's guarantee to protect the place of the mother in the home. Nor does the state help the unwed mother, or for that matter any working mother, return to work by providing sufficient day nurseries for young children. The result is a growing number of untrained, untaxed and most importantly unsupervised babyminders supplementing their own incomes by taking in the children of working mothers.

In spite of daunting hardship, the number of unwed mothers is actually growing. In the last five years the percentage of illegitimate births has risen, and the numbers of babies available for adoption has fallen, indicating that more women are choosing to keep their babies.

There has been ample speculation and little research in Ireland into the effects on children of being raised in a single-parent family. The National Children's Bureau in Britain has found that the children of unwed mothers have greater learning, behaviour and educational problems. However, these problems were found to be caused by disadvantage (economic hardship, bad housing, poor diet etc.), rather than by lack of a father.

Surveys in Holles Street hospital have found that expectant unmarried mothers received little if any antenatal care. They were subject to more birth complications than married women of similar age. Interference with the baby's oxygen supply (a major factor in brain damage) was a factor in 20 per cent of these births.

Children of deserted wives living in local authority housing on deserted wife's allowance or benefit have been shown to have more problems than children of more affluent families. One study has found that one third of these children (average age 12) have appeared in court or in a child guidance clinic in relation to home or behavioural problems. These children are not inevitably disadvantaged but are rather more prone to the problems resultant from poverty because of economic pressures, housing and social problems that might have been alleviated.

CHILDREN - BORN TO FAIL?

A recent EEC report on popular perceptions of poverty shows that 80 per cent of Irish people think that children born into poverty stand a reasonable chance of escaping from it. Statistics and studies into child development are not nearly so optimistic In fact, the story of the cumulative debilitation resultant from poverty begins not at birth, but conception. Mothers in the lower income groups are less likely to receive adequate antenatal care. Their children are more likely to be still born or handicapped or underweight at birth. By the time the children of poverty are old enough to consider "pulling themselves up by their own bootstraps" they will probably lack the necessary personal resources - health, education, and imaginative intellect.

A recent EEC report on popular perceptions of poverty shows that 80 per cent of Irish people think that children born into poverty stand a reasonable chance of escaping from it. Statistics and studies into child development are not nearly so optimistic In fact, the story of the cumulative debilitation resultant from poverty begins not at birth, but conception. Mothers in the lower income groups are less likely to receive adequate antenatal care. Their children are more likely to be still born or handicapped or underweight at birth. By the time the children of poverty are old enough to consider "pulling themselves up by their own bootstraps" they will probably lack the necessary personal resources - health, education, and imaginative intellect.

The National Children's Bureau in Britain has followed the progress of several thousand children born in one week in 1958. They have studied exhaustively the differences between ordinary children and the disadvantaged, measured in terms of family composition, low income and poor housing. (The Irish National Teacher's Organisation has defined disadvantaged children along similar lines, in an effort to identify those who are likely to need special educational treatment.)

In the British survey, almost twice as many disadvantaged babies weighed less than 5 1/2 pounds at birth than the babies from the ordinary group. (Holles Street hospital reports show that more than half of the birth defects occur in the 6 per cent of babies born underweight).

At eleven years of age more than twice as many disadvantaged British children as ordinary children were less than 4 feet 7 inches in height (height is one recognised measure of the overall development or retardation of children). Hearing and speech problems, obvious factors in the development of communication skills, were three to four times more common in the disadvantaged group. Almost six times as many disadvantaged children were either receiving or waiting to receive special educational treatment. Almost three times as many were poor readers.

In Ireland there has been no comparable study into the effects of deprivation on developing children, but the limited available Irish research, when pieced together, forms roughly the same picture of children, born in poverty, never developing the wherewithall to escape from it'.

The 1974 ESRI report on Marital Desertion in Dublin looks at the recipients of Deserted Wives' Allowance. The report clearly shows that this particular deprived group, who were for the most part in the lower income groups before desertion as well as after, experienced an infant mortality rate three times higher than the overall Dublin rate. Annual reports of Holles Street Hospital also show higher still born rates for the lower socio-economic groups.

At the moment the Medico-Social Research Board is compiling more detailed statistics on the relation between infant mortality, birth defects and socio-economic groups. This information is readily available in most western countries and is used as an index to measure how a particular society is developing.

A study carried out on the delinquent boys being assessed at the St. Michael's Assessment Unit in Finglas, showed that these boys, most of whom were from the lowest income groups and very large families, were shorter, weighed less and had a smaller head circumference than a group of local boys from the Finglas area. Possibly the most interesting aspect of this study was the assumption that since these boys had suffered such severe deprivation they would obviously be retarded in growth and development and that therefore it was more useful to compare them with nondelinquent boys from working class backgrounds and large families than the national average. The control group of non delinquents was also shorter and lighter than the national average.

The same study, examining the causes of delinquency, found the delinquent boys were less able to learn from experience and less physically agile than the non delinquents. They had a higher incidence of eye defects and lower IQs. In the past more than one third of them had sustained childhood trauma as compared with only 14 per cent of the non delinquent boys.

A Labour Party Report of 1973 looked at child development in relation to poverty. Of children who were educationally retarded, the report concluded 55 per cent were from lower income groups, 22 per cent had fathers who were unemployed, 91 per cent were from homes where neither parent was educated beyond the primary level, 26 per cent were from over crowded homes, and 48 per cent of the parents aspired to no more than primary education for their children. Of 450 primary school students in one Dublin Corporation Housing Estate 22 per cent of the children had instructional difficulties, 23 per cent were maladjusted and 12 per cent had speech difficulties.

The cause of such educational and physical retardation in deprived children is obviously multi-faceted. However, the disadvantages that begin with inadequate ante natal care and poor nutrition are quickly compounded by less easily identified problems. The pre-school in Dublin's inner city area of Rutland Street - set up on the model of the American Head-Start programme - was designed to give children from deprived backgrounds an educational boost before throwing them into the less personalised National School System. Over the years it has become apparent that the children who leave the Rutland Street school quickly lose the learning advantages they had gained, indicating the great importance of home environment and parental attitude toward developing children.

The cause of such educational and physical retardation in deprived children is obviously multi-faceted. However, the disadvantages that begin with inadequate ante natal care and poor nutrition are quickly compounded by less easily identified problems. The pre-school in Dublin's inner city area of Rutland Street - set up on the model of the American Head-Start programme - was designed to give children from deprived backgrounds an educational boost before throwing them into the less personalised National School System. Over the years it has become apparent that the children who leave the Rutland Street school quickly lose the learning advantages they had gained, indicating the great importance of home environment and parental attitude toward developing children.

State funded education is seen as one of the methods of wealth redistribution through taxation. However, it is the upper income groups who benefit most from "free education". The state spends proportionally very little on the primary school pupil, and the bulk of children from low income families are not educated beyond primary level. In 1978 the average primary school pupil cost the Department of Education £224. Second level education cost about £450 per pupil and third level more than £1,000. More than one quarter of all primary school pupils are in classes with 40 or more pupils, and 57 per cent are in classes with more than 35 pupils.

A 1978 survey of the population of Ballyfermot showed that more than two thirds of the area's 15 to 19 year olds had left school at or before 15 years of age. 17 per cent of these teenagers were unemployed. Of those at work, at least half are in jobs that require and give no training.

An earlier Department of Labour study of youth employment in Dublin's north city centre area showed that the young people of this particularly deprived part of the country were likely to have grown up in over crowded housing conditions with unemployed or marginally employed parents, received little education, be unemployed themselves or employed in unskilled and insecure jobs, and have pathetically limited aspirations for themselves. More than a third of the 14 to 18 year olds in the study lived in overcrowded homes (two or more people per room). More than half of their parents had no education beyond the primary level.

Sixty per cent of the 15 year olds and 75 per cent of the 16 year olds had left school. Of those who had left school half of their fathers were unemployed. Only half of the school leavers had themselves found work and of these well under half were in jobs that required or offered any training. The vast majority of these young people aspired to no more than their present status, although the small minority that had remained at school were more inclined to want more for themselves.

With so many young people receiving little more than primary education (40 per cent drop out before taking the leaving certificate), skills learned at the primary level are particularly important. More than 6 per cent of final year primary students are functionally illiterate in reading and writing, and most of these are from poor backgrounds. Nearly one quarter of the students entering second level schools have reading difficulties, more than one quarter of AnCO applicants in 1979 had reading difficulties, and in 1975 13.5 per cent of the boys in Saint Patrick's Institution for juvenile offenders were illiterate and nearly one third had reading ages of between 7 and 9 (the vast majority of these boys would also be from low income families.)

The findings of the National Children's Bureau in Britain are similar to the findings of various Irish studies: 58 per cent of the disadvantaged as compared with 20 per cent of the ordinary children were poor readers while only 7.3 per cent of disadvantaged and 37.3 per cent of the rest were good readers. The study concluded that high educational attainment, or the lack of it, is more associated with social class than any other single factor.

Many disadvantaged babies grow up physically retarded, under educated, and often unemployed, to become disadvantaged adults. For the most part, they will marry within their social class, at an earlier age than the national average, and soon become the parents of similarly deprived children. There is little indication that recent economic growth has done anything to halt this depressingly consistent cycle of poverty.

THE ELDERLY

A survey by the Society of St. Vincent de Paul of 1,500 old people living alone (as yet unpublished) has found that one third of these pensioners had no kitchen sink or flush toilet. One half have no hot water supply or bath or wash hand basin. The AnCO report on Youth Employment in North Central Dublin showed that a disproportionately large percentage of the population in that area consisted of old age pensioners. One third of the housing units had no bath. In neighbourhoods with the largest percentages of elderly people, there were baths in less than half the homes.

The income of the single old age pensioner amounts to about one fifth of average male industrial earnings. About 134,000 of pensioners are in receipt of the means tested non-eontributory old age pension of £21.00 weekly (£31.55 for a married couple). A further 61,838 collect the contributory pension. Presumably many of these people would have additional pensions from their jobs. In fact, those living in poverty in their old age are probably those who lived on limited means throughout their lives, never accumulating the assets needed to guard them against poverty in old age. Those employed by the state receive index-linked pensions equivalent to one half of their salaries at retirement and those in employment with good private pension schemes may get as much as two thirds of their salary upon retirement.

The income of the single old age pensioner amounts to about one fifth of average male industrial earnings. About 134,000 of pensioners are in receipt of the means tested non-eontributory old age pension of £21.00 weekly (£31.55 for a married couple). A further 61,838 collect the contributory pension. Presumably many of these people would have additional pensions from their jobs. In fact, those living in poverty in their old age are probably those who lived on limited means throughout their lives, never accumulating the assets needed to guard them against poverty in old age. Those employed by the state receive index-linked pensions equivalent to one half of their salaries at retirement and those in employment with good private pension schemes may get as much as two thirds of their salary upon retirement.

According to the St. Vincent de Paul pre-Budget submission, many needy pensioners spend between 40 and 50 per cent of their weekly income on food. A further 25 per cent goes on gas, electricity and fuel: Still, a cut down on food is one of the first economies old people make although medical evidence suggests that the elderly actually need more money for food and fuel simply because they are old and consequently have greater need for substantial heat and nutrition. The elderly are further penalised by the fact that they tend to buy their food at its most expensive - in local shops in small quantities.

Community welfare officers could bring up the standard of living of many old people through the supplementary welfare allowance (SWA), which at their discretion they can use to help out any needy member of the community. A recent report hy the Combat Poverty Committee shows that this allowance is under used and often used arbitrarily, depending on which community welfare officer is in charge.

In total, the incomes of 6,657 people are supplemented by the SWA at an average weekly rate of £2.42. The poverty committee report shows that just 2.4 per cent of non-contributory pension recipients were also receiving SWA. 3.6 per cent of contributory pension recipients - who collect more money than the non-contributory pensioners and are more likely to have another pension - were in receipt of SWA. The report concludes not that this tiny percentage of pensioners had extraordinary needs, but that few old people knew there was such an allowance or felt they were entitled to it. A survey of community welfare officers shows the arbitrary nature of the scheme, some officers normally pay the allowance in particular circumstances, others do not.

Most old-age pensioners pay little in rent. The lucky ones are in local authority housing. Of those in controlled tenancies, many live in the kind of horrific conditions which have been widely publicised by organisations like "Alone". The landlords cannot raise the rent and therefore find modernising or repairing their property not economically feasible. At the same time many of their tenants are living in conditions which do not meet minimum standards. Elderly tenants opt for the secure cheap roof over their heads, albeit a leaky one, rather than seeking more expensive alternative accommodation.

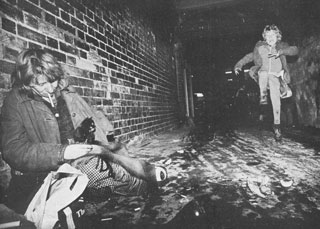

"Alone" estimates that there are up to 5,000 old people living alone in the Dublin area in very bad conditions. About 1,000 would be living in absolute squalor. Most of these would be controlled tenants, many living in isolated near-empty houses that have been vacated by other controlled tenants who have either died or been rehoused by the local authority.

Inadvertently, the operation of the points system for housing by Dublin Corporation actually encourages decaying living conditions. As living conditions deteriorate the pensioner on the housing list accumulates more points. The pensioner stands an increasingly good chance of being rehoused and the landlord of vacating his property of controlled tenants.

HOUSING CRISIS

There are about 35,000 families on local authority housing lists throughout the country, representing 90,000 people including about 30,000 children. The numbers indicate a high proportion of those waiting for housing are young couples with just one child - not huge families as once was the case. This apparently encouraging trend possibly explains another trend, the decreasing numbers of houses built by local authorities.

There are about 35,000 families on local authority housing lists throughout the country, representing 90,000 people including about 30,000 children. The numbers indicate a high proportion of those waiting for housing are young couples with just one child - not huge families as once was the case. This apparently encouraging trend possibly explains another trend, the decreasing numbers of houses built by local authorities.

From January to October 1979, 4,200 local authority houses were completed. In the same period, 17,367 private houses were built. The percentage of new housing built by local authorities has dropped from 32.7 per cent (about 8,800 houses) in 1975 to 23.9 per cent (about 6,200 houses) in 1978 and less than 20 per cent in 1979. In one local authority area - Dublin County Council - the official housing need has been estimated at 1200 houses per year. In the past four years the same area has averaged 650 houses annually.

This drop in public housing has coincided with massive increase in the cost of private housing, putting private housing out of the financial reach of many young couples. In the last three months the price of houses in the under £20,000 bracket has risen by as much as 10 per cent. In Dublin this combination of events has been officially recognised as a housing crisis.

The policy which enables local authority tenants to purchase their houses ( and resell them on the booming property market) has further diminished the public housing stock. Since 1972 50,000 local authority houses have been sold nationally, and 20,000 have been sold in Dublin. With the cost of private housing rising, this reduces the numbers of low cost houses available to young families.

Local authority tenants are housed after qualifying for available housing through a points system. The criteria for the accumulation of points varies from area to area, nonsensically at times. In some areas a wife whose husband deserts actually loses housing points because there is less over crowding. In Dublin a couple living in a 'one room flat with three small children do not necessarily have enough points to be rehoused. Generally they can look forward to a two to three year wait on the housing list. If they develop health problems (and the chances are high in those conditions) they might gain a few points. Alternatively, if their living conditions deteriorate drastically they may qualify for emergency status and catapult over the bewildered heads of those who have been waiting patiently for years.

The problems of living on the housing list can be pretty harrowing. One Dublin County Councillor, Eithne Fitzgerald, has said, "I know hardly any woman on the housing list who is not on Valium." Overcrowding is the biggest problem. Margaret Sheehan's study of Home Assistance recipients for 1974 found that in the households that contained seven or more persons, half had four rooms or less. The more recent AnCO study on youth employment in North Central Dublin showed that in this area almost half of all housing units were overcrowded and a further 20 per cent were severely overcrowded.

In the neighbourhood with the most severe overcrowding, three quarters of the housing units were owned by the Corporation, indicating either large families or several generations of the same family occupying the same Corporation flat. The effects of this kind of overcrowding on marital relationships and child development are obviously detrimental. (The INTO lists overcrowding in the home as one of the identifying features of a child who is likely to be educationally disadvantaged.)

HEALTH

Peter Townsend's report on poverty in the UK shows a conclusive relationship between poverty and ill health. Townsend found 11.2 per cent of men in the manual classes to be disabled as compared to 7.4 per cent in the non manual classes. In general, the disabled had lower social status, low incomes, and few assets. More of the disabled than able bodied lived in poor housing, missed cooked meals, had poor facilities, were short of fuel and ate meat infrequently.

In Ireland there are about 23,000 people collecting the means tested Disabled Person's Maintenance Allowance of £20.25 and a further 14,500 collecting the Invalidity Pension at a basic personal rate of £22.05. Although the disabled receive priority housing from local authorities, there is no special policy as to where they are housed. There have been cases of the disabled being housed in the high rise flats of Ballymun. The travel allowance which affords some freedom to some of the handicapped, does not cover others who by bureaucratic regulation are seen to be fit enough to travel by bus.

In Ireland there are about 23,000 people collecting the means tested Disabled Person's Maintenance Allowance of £20.25 and a further 14,500 collecting the Invalidity Pension at a basic personal rate of £22.05. Although the disabled receive priority housing from local authorities, there is no special policy as to where they are housed. There have been cases of the disabled being housed in the high rise flats of Ballymun. The travel allowance which affords some freedom to some of the handicapped, does not cover others who by bureaucratic regulation are seen to be fit enough to travel by bus.

One man with no legs below the knees has to travel by bus from Ballymun coping with delays and queues, to have his artificial legs adjusted in a clinic in Dun Laoghaire. He and others have also had to suffer the indignity of returning to the Department of Social Welfare from time to time to see if their disabilities are still evident and their eligibility as recipients, still relevant. The anomolies in the social welfare system particularly affect disabled people as there is no allowance for their dependants. They have to apply for the Supplementary Welfare Allowance which, because it is deemed a temporary allowance was increased by just 20 per cent at the last budget (rather than 25 per cent). Consequently, a family of five headed by a disabled person received about £10 per week less than the same sized family of an Infectious Disease Maintenance Allowance recipient.

Townsend's report also found that in Britain prolonged illness is also linked with low income. Nearly twice as many of those who had been ill for more than ten weeks lived in or on the margins of poverty than those who did not. Significantly more of those complaining of nerve trouble were also from the lower income groups.

A 1974 report by Margaret Sheehan and the Irish Council for Social Welfare, The Meaning of Poverty surveyed Home Assistance recipients and found that psychiatric illnesses were the most frequently mentioned illnesses. More than half of those who had had a psychiatric disorder were under 39 years of age. Three fifths of households surveyed had at least one member with some long term illness.

The reports of the Medico-Social Research Board show that between 1972 and 1977 there was a marked increase in the rate of admissions to psychiatric hospitals in the lower income groups. The rate for unskilled manual workers was up by 50 per cent.

For semi-skilled manual workers the rate is up by 35 per cent, by 28 per cent for farmers and the intermediate non manual grades, and by 9 per cent for skilled manual workers. For employers, managers and professionals the rates for admissions have fallen by between 10 and fifteen per cent.

Taking the unskilled manual group alone, not only has the rate of admissions risen beyond that of any other socio-economic group, the admission rate in each of the various categories of psychiatric disorders is greater than the average of all groups, particularly in areas such as schizophrenia, neurosis, alcoholism and mental handicap.

The lower socio-economic groups are also over represented among the mentally handicapped, particularly among those who's handicap is not caused by any identifiable brain damage. Mild mental handicap therefore is probably caused by environmental factors rather than organic ones.

Sile O 'Connor of the Medico-Social Research Board has surveyed 400 problem children with IQ's greater than 50 who have been sent to various centres in four counties for assessment. 60 per cent of those referred came from homes headed by semiskilled, unskilled or agricultural workers. The remaining forty per cent were from the skilled manual and non manual classes. In relation to the distribution of the population the lower income groups were over represented.

A greater proportion of those with reading and language difficulties were also in the lower income groups. Nearly half of those in the lower income group were found to be mildly mentally retarded, as compared with 37 per cent of the other group. Of those not retarded (i.e. IQ over 70), nearly one quarter of those in the low income groups needed special education, as compared with just 10 per cent of the other group.

Rural Ireland

Some rural poverty and deprivation is actually caused indirectly by recent advances in farming technology. The revolution in agriculture has resulted in a rationalisation of production which favours the larger farming units causing the development of a dual structure within the farming community - large efficient farms and small uneconomic ones. Two classes of farmers have been created in recent years and the gap between them is actually increasing although on the whole the farming industry is prospering.

Population trends in recent years have indicated a move away from rural areas to urban, with the old being left behind in proportionately large numbers. Of the remaining farm households, 50 per cent earn less than £2,000 annually according to 1978 figures. 50 per cent of farms are less than 50 acres. Many of these are part time farming households which rely on additional income from employment or social welfare payments. Of the full time farmers some 30,000 earned less than £2,000 in 1978. Most are on small farms and the vast majority live either in the three counties of Ulster or in Connacht.

Population trends in recent years have indicated a move away from rural areas to urban, with the old being left behind in proportionately large numbers. Of the remaining farm households, 50 per cent earn less than £2,000 annually according to 1978 figures. 50 per cent of farms are less than 50 acres. Many of these are part time farming households which rely on additional income from employment or social welfare payments. Of the full time farmers some 30,000 earned less than £2,000 in 1978. Most are on small farms and the vast majority live either in the three counties of Ulster or in Connacht.

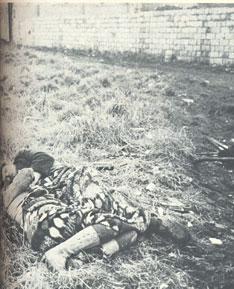

In remote areas, where a disproportionately large percentage of the population is elderly, public services like hospitals and local authority housing schemes are also being run down, further isolating this section of the farming community. In some areas housing problems are alleviated by the building of pre-fabs next to deteriorating cottages rather than building housing estates that might be empty in twenty years time. In other areas, the price of land has been so inflated by foreign interest in holiday homes that local authorities will build houses only when land is provided.

The development of the agricultural industry has also had adverse effects on some sections of the non-farming rural population. Large farming operations can operate independent of the villages and local services that were once part of the farming economy. By reason of age or fixity of residence some of these people have not moved to centres of industry and are probably living in or on the margins of poverty. This group - likely to consist of small households of one or two elderly people - are worse off than the small farmers. A breakdown of percentage of regional populations on medical cards shows the highest proportion in the North-Western (63 per cent) and Western (60 per cent) health board areas as compared with 27 per cent in the Eastern and 36 per cent in the Southern health board areas.

Since the beginning of the 1970s IDA policy has favoured the establishment of manufacturing industries in rural areas in an effort to absorb the local labour force (that would have traditionally been directly involved with agriculture). To an extent this policy has been successful. In the period from 1973 to 1976, when the older industrial centres were experiencing net job losses, job creation schemes in rural Ireland were able to keep pace with the movement off the land although they didn't actually reduce the numbers of unemployed.

Disproportionately large numbers of Unemployment Assistance and Disabled Persons Maintenance Allowance recipients live in remote areas, particularly in the Western Health Board area. These are probably people who aren't quite old enough for the old age pension, and have never worked in insured employment. The DPMA is particularly attractive because for the person with no dependants it's worth more than unemployment assistarlce and in many areas it is sent out by post which is handy for people living in remote areas with no transport.

Travellers

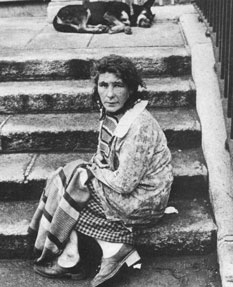

In the case of the most visible manifestation of poverty in Ireland that involving travelling people - the situation has improved significantly in the last two decades, although it still remains a considerable problem.

There are some 2,000 families of travellers in Ireland representing about 13,500 people. Of these more than 6,000 are school aged children. Half of these families have been "settled" to some degree by local authorities either on approved sites, in the transitional chalets, or in houses. The other half live in the squalor of roadside camps.

In 1977 there were about 250 families in the Dublin area. Today there are 465. Because travellers can no longer eke out a living in rural Ireland as itinerant tinsmiths, handymen, and horse dealers, they are moving to Dublin and other cities to collect the dole, deal in scrap and beg. Those who have moved to Dublin are also more likely to be settled in approved sites. Of the 465 families in the Dublin area less than forty per cent are still on the roadside. 80 have been housed, 165 are in special chalets (originally designed as transitional housing between travelling and settled life), and 42 families are camped in the two new approved sites (which provide caravan space, running water and toilet facilities).

In 1977 there were about 250 families in the Dublin area. Today there are 465. Because travellers can no longer eke out a living in rural Ireland as itinerant tinsmiths, handymen, and horse dealers, they are moving to Dublin and other cities to collect the dole, deal in scrap and beg. Those who have moved to Dublin are also more likely to be settled in approved sites. Of the 465 families in the Dublin area less than forty per cent are still on the roadside. 80 have been housed, 165 are in special chalets (originally designed as transitional housing between travelling and settled life), and 42 families are camped in the two new approved sites (which provide caravan space, running water and toilet facilities).

Although most itinerant men would collect unemployment assistance, very little of this is used to support the family. It is the wives' task to provide for the daily subsistence of herself and her children. This they do through begging and the children's allowance.

As itinerant families settle, living conditions for their children improve however slowly. The average family is twice as large as the national average. In 1961 more than 11 per cent of itinerant babies died in the first year of life and many more died in early childhood. (In 1961 only 23 per cent of itinerants were over 30 years of age.) Access to medical facilities for travellers living permanently in urban areas has improved this situation more mothers are receiving some antenatal care, more children are born in hospital and more children receive medical care through the schools.

The vast majority of travellers are illiterate. In 1960 only 114 travelling children were attending schools. Today there are some 3,000 in school on a reasonably regular basis. In all there are 10 special pre school centres throughout the country, 60 special classes for travelling children and 5 training centres.