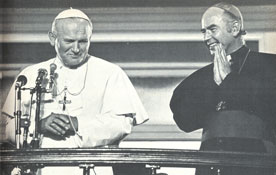

A Pilgrim of Peace

The Pope's mission to Ireland was not just to plead for an end to violence but to chastise the Irish bishops for failing to identify with the poor and repressed.

There has been no greater or no more intense communal religious experience in Irish history. The significance of the three-day visit to Ireland by Pope John Paul II is certain to be profound and enduring but the nature of that significance is yet obscure.

Over two million Irish people attended ceremonies presided over by the Pope and the entire Irish nation and much of the rest of the world witnessed him intervene directly in the Irish conflict with a personal plea to violence couched, significantly, in terms not of condemnation but of forgiveness.

Over two million Irish people attended ceremonies presided over by the Pope and the entire Irish nation and much of the rest of the world witnessed him intervene directly in the Irish conflict with a personal plea to violence couched, significantly, in terms not of condemnation but of forgiveness.

The Drogheda speech was drafted personally by the Pope and worked on over several days before his departure from Rome. It is seen in the Vatican as a prelude to further interventions in the conflict and the beginnings of an initiative by the Irish primate, Cardinal a Fiaich and his English counterpart, Cardinal Hume, both of whom have been asked by the Pope to work together in conjunction with other Christian churches to· promote reconciliation in Ireland.

The Pope's personal authority and magnetism, coupled with the enormous prestige of his office, virtually ensures a revival of religious fervour in Ireland and a significant change in the political climate in Northern Ireland in relation to Violence. Indeed he explicitly acknowledged this himself when he said: "do not lose trust that this visit of mine may be fruitful, that this voice of mine may be listened to".

The Pope has also sought to mobilise the Irish bishops on important social questions. In a private address to the bishops on the eve of his departure he sharply criticised them for remaining passive in response to 30 letters and communications from Pope Paul VI asking them to take an "oppositionist" position to the Irish establishment.

The two pronged nature of the Pope's strategy in Ireland: a plea to revolutionaries to renounce violence and a direction to the Irish hierarchy to identify with the poor and oppressed in all parts of Ireland. A Vatican official, travelling with the Papal party, said on the night of Sunday, September 30, that the Pope's message could be illuminated by the words of St. Thomas of Canterbury: "the faith and social ethic demand respect for the authority of the state, but that respect must fmd its expression in individual acts of mediation, in persuasion, in moral influence and firmly expressed demands. Precisely because we are denied the right of defence by the sword we have a special right and duty to influence those who wield the Source of authority. It is out duty when faced with secular authority to become the spokesmen for the moral order" .....

While the Pope expects his influence will have a socially radicalising effect on the Irish church, it is by no means certain that this is what will happen. The implicitly triumphalist nature of much of the festivities inevitably fosters the reactionary elements in the Irish church, the concentration on Mariology, which is implicitly antipathetic to women's rights, and the assaults on materialism, also contribute to a strengthening of the conservative elements in Irish catholicism.

It had been the Pope's intention to visit the ecumenical service in St. Patrick's Cathedral on the night of Saturday, September 29, but by the time he had completed his other engagements he was personally exhausted and the service was nearly over.

In spite of that intended gesture and his appeal to Protestants to view him as "a friend and brother in Christ", the visit may add to the sectarian tensions in Irish society. This danger is given added edge by the Taoiseach's blunder on the Saturday night in referring to the Catholic Church as "our church" and the Catholic faith as "our faith" - inadvertant casualness no doubt, but to many reflective of the denominational character of the southern Irish state.

The emphasis on Mariology is also divisive and the inevitable triumphalist response of much of Catholic Ireland to the visit may harden sectarian attitudes even further.

There is also the point that the two most reactionary periods in recent Irish history followed major religious events: the Eucharistic Congress and the Marian Year in the fifties. In both instances there were other factors in operation but these precedents give some validity to the recurrent claim in left wing circles that the Pope's visit will be followed by a period of reaction.

While the Pope may be enjoining the Irish bishops to break their ties with the Irish establishment, the fact is that it was the Irish establishment which ensured the huge organisational success of the visit. One joke going the rounds among Government members and the press prior to the Government's meeting with the Pope on the Saturday night was that if only those who ran the Papal visit could be allowed to run the country we would be all right.

While there were enormous traffic jams, especially in Mayo and Louth after the Pope's visits there, otherwise arrangements went smoothly, although security precautions were at once over-rigid and again almost non-existent. The facilities for the world's press were, according to most foreign correspondents covering the visit, at the least comparable to the best elsewhere.

While there were enormous traffic jams, especially in Mayo and Louth after the Pope's visits there, otherwise arrangements went smoothly, although security precautions were at once over-rigid and again almost non-existent. The facilities for the world's press were, according to most foreign correspondents covering the visit, at the least comparable to the best elsewhere.

Most of the people responsible were from various governmental agencies, plus representatives from most of the country's PR companies.

By his visit to Ireland, the Pope has developed his philosophy of "religious" journeys as methods of presenting the Papacy within the context of modern society. Within the Roman curia there were objections raised to the idea of a Papal visit to Ireland. One of the principal objections was the theory that the Pope should go only where the situation was relatively calm. The thinking behind this was that the Papacy should be neutral in world politics. According to this theory, the sole motive for the Pope to leave the Vatican would be a pastoral one, carefully avoiding any risk of involving the Papacy in political conflicts.

John Paul II totally rejected this idea. He pointed out that the first journey outside Italy taken by a Pope in modem times was that of Paul VI, who went to Jerusalem in January 1964. If a Pope has carefully to avoid setting his foot anywhere certainly he would have avoided the arena where long and cruel wars between Arabs and Israelis had been going on and off for the last 30 years. John Paul II also maintained that the presence of the Pope should be made visible in the most difficult areas of the world.

As a result the papal drive through the crowds was delayed, increasing the impatience of the crowd, many of whom blocked avenues in breach of the now lax security. The blocking of avenues meant that one section of the crowd, cut off and in a hollow, could follow papal progress only by listening to the cheers as the Pope drove through the multitude to the tune of "Slattery's Mounted Foot" and shouts of "Fine girl ya are".

"John Paul Rules OK", read the banner facing Our Lady of Lourdes church in Sean McDermott St. It was 8 p.m. and the Papal motorcade should have been at Aras an Uachtarain an hour ago. Hundreds of people waiting on the footpaths and on stands outside the church sang and wondered if the Pope would really stop at their church. Some had radios and followed the progress of the motorcade. A shout of "He's in Whitehall" and a cheer went up. The flats across from the church were festooned with bunting, some windows alight others dim but all crowded with faces. High above the street the dark figures of children, almost invisible against the night sky, moved back and forth. Further down the street a banner hung across the road. "Peace to all who pass this way", a sentiment extended to more than the Pope, from the people of an area steeped in a reputation not of their own making.

Then the RTE camera operator on the crane above the crowd was suddenly alert. Then the helicopter was overhead, the police cars arrived, the motorcycles, and, finally the oddly shaped Popemobile. The Pope waved, the face beneath the broad-brimmed red hat tired and unsmiling, and dozens of flashbulbs threw an explosion of light on the scene. Then he was gone. Some of the children ran in the wake of the motorcade as soldiers and Gardai tried to block the road.

In front of one of the tenements, the windows boarded where tenants abandoned the building to the rats, four yellow-sashed stewards began dismantling a makeshift altar, blowing out the candles. The 263rd Pope, the only one to visit their street, was gone. The next day the Gardai were putting out radio appeals for a three-year old child who disappeared in the chaos.

The Pope was convinced that he must make his physical presence felt in Ireland because with his sense of history he felt that as the head of the church he had a special responsibility towards Irish Catholicism. He believed that a continuation of the conflict would have irreparably damaged the credibility of the Catholic church both in Ireland and in the rest of the world.

How could he have gone to speak of peace before the United Nations in the Glass Palace in New York without first having thrown all his moral weight into an effort to resolve a conflict in which one of the parties is described as followers of the Church of Rome? If this was the main reason for the Pope's decision to make a stop over in Ireland on his way to the United States and to speak at the UN it is also to be remembered that the whole of his initiatives taken during the three days in Ireland represented an important indication of the political thinking of the Papacy.

How could he have gone to speak of peace before the United Nations in the Glass Palace in New York without first having thrown all his moral weight into an effort to resolve a conflict in which one of the parties is described as followers of the Church of Rome? If this was the main reason for the Pope's decision to make a stop over in Ireland on his way to the United States and to speak at the UN it is also to be remembered that the whole of his initiatives taken during the three days in Ireland represented an important indication of the political thinking of the Papacy.

In his address at Drogheda on September 29, Pope John Paul II has given a new interpretation to the traditional theme of peace preached by his predecessors. All the Popes for centuries have spoken of peace as part of their duty as teachers. Nevertheless this word of peace, both in speech and writing, delivered by different popes, has always been too abstract and general to play a concrete role in constructing the reality of peace in the complex story of our modern age. The great principles are valid and an indifferent world must be frequently reminded of it. But once the word has been proclaimed the world has been left to grapple with its own problems in the light of Papal teaching.

This Pope has not hesitated to use the weight of his moral authority to break through the curtain of abstraction. At Drogheda he spoke of discrimination and of terrorism. He has taken the abstract idea of peace to where it is being oppressed and violated and not only where there is an armed conflict and a struggle for justice in one country, but where it is necessary to speak of the geography of the conscience in the matter of peace.

After listening to his personalised appeal to the young militants in the ranks of the terrorist organisations it was natural to remember that only a man who had personally lived through this problem of armed resistance for a just cause could use the type of language which he did and make his appeal realistic. The man who spoke of nonviolence was the same man who as a youth in Cracow had taken part in the underground resistance against the Nazi occupation and seen many of his friends die as a result of torture by the Gestapo. As a Pole he was in a position to understand the mentality and the reasoning of the all those who are, or believe themselves to be, unjustly oppressed. In a different situation he has made his own the ideas of the Brazilian bishop Helder Camara, on "violence and the peace makers" and on "active non-violence".

His address at Drogheda was the result of mature consideration at the highest levels inside the Vatican secretariat of state regarding the Irish situation. The failure of all the initiatives undertaken by the British Government to find a political solution had brought all the parties to a full stop and the situation was becoming even more desperate as there seemed no hope of a political way out.

It must also be remembered that historically the Catholic church in Ireland has stood for the safeguard and refuge of the national identity and the interests of the people, Therefore the Irish church could not easily produce effective inititives. The bishops have been castigated for not having sufficiently defended the need for justice for fear of losing their links with the middle classes and for fear of upsetting the protestant Loyalists. Seen from Rome the outlook was that of a progressive alienation of the people from the church despite the regular Sunday Mass attendance. It was feared that there was developing a ritual religiosity which would not be sufficient to resist the rapid progress of secularisation nor respond to the demands of the social needs of the time.

Thus there were many factors which suggested to the Vatican that some attempt must be maqe at a high level to reverse the tendencies both on the political and religious plane. The unjust social conditions about which the Catholics in the North of Ireland complain were too obvious because the Irish bishops had continued to remain silent and passive in spite of the cries of the people and they were losing their credibility as the moral teachers of the people.

Thus there were many factors which suggested to the Vatican that some attempt must be maqe at a high level to reverse the tendencies both on the political and religious plane. The unjust social conditions about which the Catholics in the North of Ireland complain were too obvious because the Irish bishops had continued to remain silent and passive in spite of the cries of the people and they were losing their credibility as the moral teachers of the people.

On the other hand, the participation of Catholics in terrorism was rending the Church in half and throwing it under a shadow of suspicion in its relationships wIth the British authorities. And the situation in the North was damaging the cause of ecumenism, which was making headway between Catholics and Anglicans.

The information that the Vatican had indicated that there was a slow but significant loss of consensus about the methods and the role of the terrorist organisations among the ranks of ordinary Catholics. According to the best information in the highest circles in the Vatican, the Catholics were being gradually alienated by tIle militancy of the IRA. Furthermore, the Vatican had reached the conclusion that forces external to the cause of Irish independence were operating to maintain and foment this crisis in the heart of Western Europe, inside the Common Market and in Britain's backdoor.

Mairead Corrigan and Betty Williams, the Northern Ireland Peace Movement leaders, played an important part in the background to the visit. They had been invited to an aµdience with the Pope in November 1978 when he had been consulting several sources to learn how best he might intervene in the Irish situation. The two women convjnced him that nine years of civil war had proved that violence is incapable of resolving serious problems arising from the kinds of injustices from which the country was suffering. To obtain political and social answers to the questions that would be effective there must be one precondition: a change in people's mentality. An intervention by the Pope would be most useful in convincing the men of violence that they had taken the wrong course and to isolate them by mobilising the masses of the people who yearn for peace. But at the same time the Catholic Church would have to take on great responsibilities in contributing to a solution of the social questions.

In essence, this was the outline of his scheme on which the Pope had based his vision of a journey to Ireland. He had taken it on himself personally to consider a visit to Armagh, the ancient see of Irish Christianity and the see of the Primate of all Irelancd, Cardinal Tomas 0 Fiaich. The Pope wanted to go back to the roots of the Irish church and visit the ancient seat of St. Patrick. Political difficulties were raised, but these didn't seem illsuperable when Cardinal 0 Fiaich handed to the Pope an invitation from the representatives from the other churches in the North of Ireland who declared that they would be happy to see the Pope make a stop over in Armagh. There still remained certain resistence by the British government to be overcome.

Negotiations were still in progress on August 27 when Lord Mountbatten and 18 British soldiers were killed in attacks for which an extreme wing of the Provisional IRA, "the Catholic side",' claimed responsibility. The Papal Nuncio, Dr. Alibrandi, had been playing a simple executive role in preparations for the Papal journey and he had declared the day before that it would be quite possible for the Pope to visit a village in the North, but the Vatican authorities regarded this as a diplomatic blunder by the Sicilian while delicate negotiations with London had not yet been completed.

However, with these murders the whole of the Papal programme had to be changed. Drogheda was chosen instead of Armagh and it represented a symbolic historic spot within the diocese of Armagh. from which the significance of the call which the Pope intended to make could be heard. He wrote this address personally. it being the main one of the ten that he had to prepare for the visit.

However, with these murders the whole of the Papal programme had to be changed. Drogheda was chosen instead of Armagh and it represented a symbolic historic spot within the diocese of Armagh. from which the significance of the call which the Pope intended to make could be heard. He wrote this address personally. it being the main one of the ten that he had to prepare for the visit.

At the same time he had set in train contacts with leaders of the Protestant churches, both in the North of Ireland and in England to work with Cardinal 0 Fiaich and Cardinal Hume in preparing an jnitiative to sustain his call for peace. Out of all this was born the address delivered at Drogheda. He hadn't intended to propose a political initiative on behalf of the Catholic church, but to create the preconditions for a political initiative to be taken up by the interested governments.

At the same time the Pope has mobilised the Church to contribute towards resolving the social question, even though the lavish expenditure in the organisation of his visit is npt a good example. It is quite probable that the Vatican intends to exert pressure on the Irish community in America to give concrete support, tlnancially as well as otherwise, to social initiatives to be undertaken by the Catholic church in the North of Ireland.

Giancarlo Zozola reports on the Pope's flight to Ireland:

The leading Italian newspaper, La Stampa headlined on the day before the Pope left Rome for Ireland: "A Trip to the Edge of a Volcano". It was considered the most potentially explosive journey a Pope had ever undertaken in modern times.

There were the most rigorous of security precautions at Rome's Fiunicino airport, with many journalists of the 100 that were to travel with the Pope, having to check in four hours prior to the departure. The Pope arrived by helicopter from the Vatican and to the cheers of only a few airport workers who had gathered to see him depart, he boarded the Aer Lingus 737, where a special sitting room and sleeping area had been provided for him - the latter for use on the trip to America.

For most of the journey the Pope sits in the upstairs compartment of the aeroplane chatting with the Secretary of State, Cardinal Casaroli. With just an jour to go before landing at Dublin he walks into the rear compartment occupied by the journalists and immediately there is pandemoqium. Reporters scramble across seats, photographers jostle for position, a typewriter gets crushed in the melee, later on there are reports that there had been, a punch-up among some Italian journalists and others.

For most of the journey the Pope sits in the upstairs compartment of the aeroplane chatting with the Secretary of State, Cardinal Casaroli. With just an jour to go before landing at Dublin he walks into the rear compartment occupied by the journalists and immediately there is pandemoqium. Reporters scramble across seats, photographers jostle for position, a typewriter gets crushed in the melee, later on there are reports that there had been, a punch-up among some Italian journalists and others.

Questions are shouted at the Pope, "are you going to excommunicate the IRA?". The Pope smiles and replies, smilingly: "I am going there only to pray. My journey is a journey of prayer." But the Catholic terrorists will be excommunicated: "What? Oh no, no, oh my God let us leave .... " The rest of the sentence is lost in the chaos.

He is asked how he interprets his journey to Ireland and he says that it is a form of the presence of the Pope in the Irish situation and then that he is thinking of changing the nature of his journeys.

"In what sense do your journeys need to be changed?"

"Perhaps in the sense that it is usually the journalists who ask the Pope questions. But perhaps now is the time for the pope to ask them questions."

"Do you think it is the function of the Pope to listen?"

"Yes, also because often it is much easier to listen than to talk. The Pope should listen above anything else."

"You are a pilgrim for peace, into difficult areas?"

"Peace must be announced and proclaimed everywhere that is my mission. It must be announced especially where it does not exist".

"Are you disappointed not to be able to go to the North?"

"I am truly disappointed. I intended to go there, especially to Armagh, it is the most ancient seat of Irish Christianity and the seat of the Primate."

"We are English journalists."

"Have the English people taken account of what the Pope's visit means? You should write that the Pope is going

to Ireland as a shepherd."

It was a few minutes before 10 am, local time. We were circling over the green heart of the capital city and we could see the immense crowd that covered Phoenix Park waiting for the Mass to be celebrated by the Pope. Awaiting him in Ireland was a programme of 50 hours with hardly a break, hardly time even for a short nap. No one can foretell whether this visit will be remembered as the first year in a new era of peace. The breath of war was already hanging there in the atmosphere at the airport, surrounding the Pope as he descended the steps from the aircraft and went down on his knees to kiss the soil of Ireland. The wind stretches out the Vatican flags and from the distance comes the muffled sound of the cannon firing a salute. There wasn't at the airport the joy as there was at the airport in Mexico City. There was no other music other than the official anthems and there were lines of distinguished guests and bishops in close ranks. In the distance groups of faithful under the tight security of hundreds of police broke out every now and again into shouts of welcome. Everything was under strict control. The first newspaper headlines that one saw was "faith and fear". Would it be different after the weekend spent in Ireland by Pope John Paul II?

It was a few minutes before 10 am, local time. We were circling over the green heart of the capital city and we could see the immense crowd that covered Phoenix Park waiting for the Mass to be celebrated by the Pope. Awaiting him in Ireland was a programme of 50 hours with hardly a break, hardly time even for a short nap. No one can foretell whether this visit will be remembered as the first year in a new era of peace. The breath of war was already hanging there in the atmosphere at the airport, surrounding the Pope as he descended the steps from the aircraft and went down on his knees to kiss the soil of Ireland. The wind stretches out the Vatican flags and from the distance comes the muffled sound of the cannon firing a salute. There wasn't at the airport the joy as there was at the airport in Mexico City. There was no other music other than the official anthems and there were lines of distinguished guests and bishops in close ranks. In the distance groups of faithful under the tight security of hundreds of police broke out every now and again into shouts of welcome. Everything was under strict control. The first newspaper headlines that one saw was "faith and fear". Would it be different after the weekend spent in Ireland by Pope John Paul II?

Vincent Browne reports:

The Pope looked very much older than his 58 years or his television or photographic image, even at 10 a.m. on the Saturday morning. A foreign journalist who had been with him at both Mexico and Poland said he seemed more hunched and tired at the airport in Dublin - he had bounded from the plane in Warsaw.

He did the rounds of the bishops, the Diplomatic Corps and the Government with characteristic witticisms. At one stage he lifted a baby girl from the crowd and when the baby screamed for her mother he handed her back, commenting "bad Pope".

In the helicopter to the Phoenix Park he was very moved by the size and enthusiasm of the crowd.

Late that night back at the Papal Nunciature he was scheduled to meet members of the Government and Diplomatic Corps. His schedule was then running two hours behind and ministers waited around, first on the steps of the Nunciature and then in the main reception room. When the Pope arrived he first appeared at the door of the room, then withdrew to confer with his staff for a while just outside the door and he then entered to the tentative applause of the Government ministers and their wives. Jack Lynch had to ask him to step back to behind the microphone to receive a gift and listen to the words of welcome. Lynch spoke extemporaneously and nervously and blundered into the remarks about "our faith" and "our church".

The Pope then spoke, reading from a script. The deep baritone was obviously exhausted by then and he seemed almost on the verge of collapse. His face was ashen, his shoulders drooped and yet there were three more speeches and functions.

After the speeches he moved around shaking hands with Govemment ministers and their wives and then made very stilted small-talk with Mrs. Lynch and Mrs. Colley before leaving.

He was back inside within minutes to greet the Diplomatic Corps. His speech presumed a speech of welcome which never materialised. Again he went around the crowd, pausing to speak for a minute or two to the American ambassador, William Shannon. Then upstairs in the Nunciature for what must have been only a five-minute break.

The scheduling of the Pope's itinerary was one of the few major blunders of the visit. It demanded more of him in terms of physical stamina than the fittest of men twenty years his junior could have endured.

By the time he reached the 500 journalists awaiting him in the main hall in the nearby Dominican Convent he was almost speechless with fatigue - by then he had been working for 18 hours non stop. However, the enthusiasm of the welcome obviously revived him.

Bishop Edward Daly had told the journalists that the Pope would not read his scripted speech but when he came and was greeted with prolonged cheering and applause, plus a verse of "For He's A Jolly Good Fellow" he seemed to revive a little. Attempts were made to persuade him to sing a Polish song and he seemed to dice with the idea for a few moments. He was about to leave on a few occasions but returned to make a further comment or acknowledge further verses of the good fellow song. He said he was pleased to be regarded as a good fellow not a bad fellow and that at least he wasn't leaving us without something to report. "Pope two hours, too late."

Pat Brennan and Vincent Browne report:

The Drogheda speech will be remembered and quoted for centuries or for however long the Irish conflict continues to give rise to political violence.

In a carefully constructed speech, delivered in that powerful baritone voice, full of inflexion and tone, given added impact by the heavy foreign accent and the dramatic timing of emphasis he remarked on how religious conflicts are not at the root of the Northern problem, how Christianity does not permit neglect of unjust social or international situations and how it forbids seeking solutions to these problems through violence. "The command 'Thou shalt not kill' must be binding on the conscience of humanity, if the terrible tragedy and destiny of Cain is not to be repeated".

In a carefully constructed speech, delivered in that powerful baritone voice, full of inflexion and tone, given added impact by the heavy foreign accent and the dramatic timing of emphasis he remarked on how religious conflicts are not at the root of the Northern problem, how Christianity does not permit neglect of unjust social or international situations and how it forbids seeking solutions to these problems through violence. "The command 'Thou shalt not kill' must be binding on the conscience of humanity, if the terrible tragedy and destiny of Cain is not to be repeated".

From that generalised statement of' principle he went on to particularise: "The moral law , guardian of human rights, protector of the dignity of man, cannot be set aside by any person or group, or by the state itself, for any cause, not even for security or in the interests oflaw and order.

"The causes of inequalities must be identified through a courageous and objective evaluation, and they must be eliminated so that every person can develop and grow in the full measure of his or her humanity.

"Peace cannot be established by violence; peace can never flourish in a climate of terror, intimidation and death.

"I proclaim with the conviction of my faith in Christ and with an awareness of my mission, that violence is evil, that violence is unacceptable as a solution to problems, that violence is unworthy of man.

"I pray with you that the moral sense and Christian conviction of Irish men and women may never become obscured and blunted by the lie of violence, that nobody may ever call murder by any other name than murder, that the spiral of violence may never be given the distinction of unavoidable logic or necessary retaliation. Let us remember that the word remains forever: 'All who take the sword will perish by the sword'".

Then, having posed reconciliation as the alternative to violence, he spoke "in language of passionate pleading" to those engaged in violence: "on my knees I beg you to tum away from the paths of violence and to return to the ways of peace ... In the name of God I beg you: return to Christ who died so that men might live in forgiveness and peace. He is waiting for you, longing for each one of you to come to him so that he may say to each of you: your sins are forgiven; go in peace."

The power of the plea was in its coupling with forgiveness rather than in the terms of outrage and condemnation. He acknowledged that those involved in violence might be motivated by courage, patriotism and idealism, although, he argued, wrongly applied. There had never previously been a contribution to the debate on violence in Ireland which so comprehensively dealt and grappled with the rationale of those involved.

The invited crowd at the front of the audience led the applause throughout the speech but his specific personal appeal begging those engaged in violence to desist, evoked spontaneous widespread and immediate applause and enthusiasm.

The festive atmosphere early in the afternoon began to dispel as the Pope's departure from the Phoenix Park was delayed by up to two hours. The general low key mood wasn't relieved by the heavy-handed insistence of the MC that the crowd enjoy itself but spirits were immediately revived once the helicopter was seen.

Then the huge crowd, which thronged not only the fields in front of the altar but the surrounding hills, broke into a delirium of excitement.

Streaming out of the arena after the ceremonies, people were clearly moved by the intensity of the Pope's plea for peace and the general power of his personality. Some talked speculatively of going to Knock or Galway again the following day to see him again.

On the 10-hour journey back to Belfast by coach or car, it was clear from talking to people during the many stopovers to relieve the tedium of the non-stop traffic jam, that most felt both that the Pope's impact had been considerable but that it was unlikely to have any direct effect on those immediately engaged in violence.

However several (provisional) republicans acknowledged a certam dismay at the force of the plea for peace. Some put a good face on things and pointed out the Pope's mention of social justice, and the neglected responsibilities of the politicians. The men of violence were also to be found, they said, in the ranks of the British Army and the Loyalist organisations. Some, more bitterly, complained that John Hume might as well have written the speech and this alone should keep the SDLP in business for the next few months.

According to a prominent member of the Provisional IRA, later, that organisation was not taken by surpri~e. A condemnation of violence was expected. Making the best of a bad situation, he blamed the British media for exploiting the anti-IRA angle and playing down the social justice issue.

As far as using the occasion of the Papal visit for publicity purposes, the Provisionals had decided, after some debate and division of opinion within the organisation, to keep a low prome for the duration. They distributed press releases to Dublin-based foreign journalists on the Northern situation generally and left it at that. They claim that after this most recent wave of bad publicity dies down, their support in the Catholic communities of the North will return to normal.

As far as using the occasion of the Papal visit for publicity purposes, the Provisionals had decided, after some debate and division of opinion within the organisation, to keep a low prome for the duration. They distributed press releases to Dublin-based foreign journalists on the Northern situation generally and left it at that. They claim that after this most recent wave of bad publicity dies down, their support in the Catholic communities of the North will return to normal.

Other Northerners were not so sure. They didn't expect the words of the Pope to change the opinions of the "hard core" but believe that supporters and potential new members might be dissauded, and that the politicians might be prompted to seek for and find initiatives for peace.

Margaret Mullens' first son was born mentally and physically handicapped six years ago while she was living in England. He suffered from convulsions and weak lungs. When she returned to her native Tuam three years ago, she started making yearly pilgrimages to Knock. Since then, she claims, he has not been sick.

"I don't pray for a miracle, as long as my child keeps well and his chest stays clear. I feel the Blessed Lady is here every time." On Sunday she made their fourth trip to the Marian Shrine so that he could receive Pope John Paul II's blessing.

Her devotion to Mary is characteristic of the hundreds of thousands who waited in the bitter western wind and rain for the Pope's sermon. One woman from Navan, who arrived at the Knock Shrine at 10.30 on Saturday night and slept on the wet ground in order to secure a place close to the altar, explained that, "The Pope helped me to love Our Lady more".

Not everyone's devotion was expressed in the same terms. Martin Morley, who travelled from Leicester to be at the Knock Shrine for the Pope's visit, said "I've been to one Cup Final but this is far better."

Michael Naughton, who arrived from Donegal at 1a.m., said he was attracted to the Pope "by his immense sincerity". He was one of the few people interviewed who agreed that "the pope is an ultra-conservative, but he offers sufficient scope for people to find means for placing themselves within the ideology of the Church."

Pope John Paul II combined his own adulation of Mary with a call for peace similar to the stirring one he made in Drogheda the previous day. "Mother, protect all of us and especially the youth of Ireland from peing overcome by hostility and hatred. Teach us to distinguish clearly what proceeds from love for our country from what bears the mark of destruction and the brand of Cain. Teach us that evil means can never lead to a good end: that all human life is sacred: that murder is murder no .matter what the motive or end."

Monsignor James Horan, Knock's parish priest, compared the Pope's message with the message of the alleged apparition during an interview. "There was trouble in the country at that time, too. People were settling their differences by violent means. The meaning of St. John, who was in a teaching figure in the apparition, was to 'stick to mass, stick to prayer, and beseech God for help'. The people should have the courage to settle their differences by peaceful means."