A NATION OF UNEMPLOYED?

By unanimous agreement, unemployment is now the country's most daunting problem. Yet there are no reliable figures on the number of people out of work. Brendan Dowling unravels the bewildering statistical information and describes the dimension of the problem.

How many out of work?

Twelve Months ago the electorate were offered a fairly sjmple solution to a complex problem. Vote to abolish rates, motor taxes and reduce income tax and there will be a fall in unemployment of over 25,000 per annum during the next three years.

Today the issue seems a little less clear. Suddenly there is confusion over whether the commitment was to reduce unemployment or to increase employment. The Government White Paper on National Development uses the expression 'numbers out of work' which has since been interpreted by the Minister for Economic Planning and Development, Martin O'Donoghue, to mean the entire population, school-Ieavers, housewives and all who are not employed.

Thus a promise to reduce the numbers out of work (which is different to the Manifesto promise to reduce unemployment) is reinterpreted as a promise to increase employment.

The Minister's interpretation of the phrase 'out of work' is wholly his own and is found in no official statistics definitions. The Central Statistics Office define the labour force as the numbers in employment and those out of work. But the latter include few, if any, housewives, students etc. who might be major beneficiaries of any increase in employment.

The public might be totally confused by now considering that a year ago they were informed that 'real' unemployment was running at 160,000 and not the 110,000 or so on the Live Register The author, Dr. O'Donoghue, of these figures has since admitted that they they were a guess, that they cannot be estimated and that he has no way of knowing what the true level of unemployment is.

On the other hand the White Paper seems confident that even if it cannot measure the level of unemployment it can measure changes in that level. This is a neat statistical process, an explanation of which would be of interest to many economists and statisticians!

For many people the plausibility of the figure of 160,000 unemployed - apart from their apparent academic status derived from Professor O'Donoghue - comes from the notion that the total labour force is like a football ground with both terrace and stand accommodation. Suppose the stand seats represent the number of available jobs. If they are full then any new entrants to the ground must go to the terraces and, join the unemployed. Therefore the fact that there were already 100,000 plus unemployed in 1975 who were available to take any vacancies in the stands, must mean that unemployment has been swelled since then by around 50,000-60,000 school leavers.

But the matter is more complex than that although the football ground analogy may still be used. In the first place the number of stand seats maybe increasing (or decreasing) and thus swell or diminish the ranks of the employed. These extra seats may be filled by new entrants to the ground rather than those on the terraces. School-Ieavers and housewives do get jobs even while there are many unemployed. Second, seats are vacated in the stands due to retirement or death. Again many of these go to new entrants rather than those in the terraces.

The problem of identifying the flows is made difficult by the fact that the measure of the number of terraces is not comprehensive. On the one hand there are many who went through the terrace turnstiles (registered unemployed) with complimentary passes, such as small farmers, farmers sons, semi-retired persons etc. who are not really interested in a seat in the stands. On the other hand there are many - mainly school leavers, housewives etc. - who have got in over the wall without being counted at all. So the estimated number on the terraces, based on registration, includes some who are not really seeking employment but excludes others who are. Which way the balance is depends on the magnitude of the two groups.

The only guide to the disparities we have is the 1975 Labour Force Survey which attempted to find out the numbers in employmebt and those unemployed or looking for a job. In May/June 1975 the Survey found that there were 86,400 persons who were unemployed by virtue of the fact that they had lost or given up their previous jo b. In addition there were 19,900 persons, mainly school-leavers, looking for their first regular job. Together this makes a total for unemployed of 105,300. At the same time the numbers registered as unemployed totalled around 102,000. Thus even though the registered unemployment total excludes school-Ieavers, it turns out, for 1975, to be remarkably close to the true level of unemployment including school-Ieavers.

The reason is that a substantial number of persons who are on the Live Register must have told interviewers for the Labour Force Survey that they were not looking for work.

The Labour Force Survey also uncovered the fact that there are a considerable number of married women who would seek part-time work if it were available. Similarly, as might be expected given the penurious nature of the Irish student body, a fair number of students were interested in a part time job if one were available. By stretching the definition of unemployment a bit, these potential part-time workers could be included in the unemployed. But that would still leave the total well short of 150,000.

It ought to be possible to relate registered unemployment to some universally acceptable definition of unemployment - say those seeking work on a full time basis who are not now in a gainful occupation - and to discover the degree of overlap. This would highlight the extent to which the register of unemployment covers those who are seeking work but do not qualify for benefit or assistance on the other hand.

It is understood that such a study has been undertaken by the CSO and one can only presume that the Government's failure to allow it to be published reflects the explosive nature of its findings or the possibility that it fails to support the Minister for Economic Planning and Development's utterances on the subject of unemployment in the election campaign.

Whatever the level of unemployment we know that variations in the number of people employed are not necessarily reflected in the numbers unemployed. This is because the labour force is increased by school leavers in excess of those retiring, by students and school leavers who quit school or college to get a job when one becomes available, and by housewives taking up employment when a suitable opening occurs which allows them to combine work and home duties.

Can the Government cope?

Studies by Professor B. Walsh have indicated the magnitude of the task to reduce unemployment over the foreseeable future. Between 1976 and 1981 the labour force is expected to increase by 87,000 persons or 17,400 per annum, if the high projections are assumed, and by 47,000 or 9.4 thousand per annum if the low projections are assumed. The variation is due to the fact that participation rates - i.e. the proportion of the population engaged in employment - are changing and if these rise the labour force will rise and if they fall the labour force will show slower growth.

Over the 1960s participation rates tended to decline because of the introduction of free education and the sharp reduction in the age of marriage. On the other hand the participation rate for married women has been rising and, although still well below European standards, could tend to boost the labour force in future years.

In its recent White Paper the Government would appear to have adopted the 'low' estimate of Brendan Walsh, presumably hoping that any increase in employment or reduction in unemployment will not encourage greater numbers to leave school rather than staying on as so many appear to have done during the recession. The adoption of the lower projection makes it ,possible to project lower unemployment for a given growth in total employment.

The White Paper projections must be seen in the context of recent experience in achieving any reduction in unemployment. The most comprehensive figures we have are those prepared by the CSO each year and are estimates of nonagricultural and agricultural employment, the numbers out of work and the total labour force. The data are based on census classifications and intermediate years are estimated on the basis of trends in employment and registered unemployment.

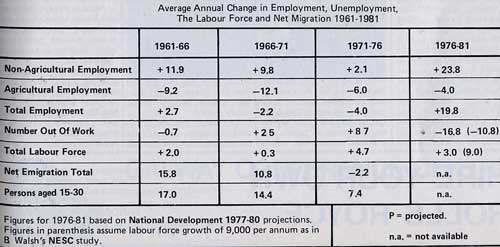

In the accompanying table the average increase or reduction in employment, both agricultural and non-agricultural, are set out along with the changes in unemployment and the total labour force. The figures are annual averages for the intercensal periods. It can be seen that 1961-1966 was the most successful period of the past fifteen years or so in generating an increase in both total and non-agricultural employment. But in spite of the increase in total employment of 2,700 a year the reduction in unemployment was only around 700 a year. This was because the labour force was increasing by 2,000 a year.

If one looks at the net migration date for the period it can be seen that this increase of 2,000 in the labour force was in spite of net migration of 15,800 per annum in the period and an enormous net migration rate of 17,000 per annum for those in the 15 - 30 age group. Clearly in 1961 - 66 the growth in employment was far from adequate to cure unemployment and to reduce to zero emigration, especially of the young.

In the period 1966 - 71 the growth in non-agricultural employment was lower and this exacerbated the increase in the

numbers leaving farm employment. The result was that total emploment fell by over 2,000 per annum, setting total employment back to pre-1961 levels while unemployment rose by 2,500 per annum. The labour force showed little growth of only around 300 per year. Why was this?

The migration figures indicate a slowdown in the outflow to just over 10,000 per annum with an outflow of over 14,000 per annum of persons aged 15 - 30 being offset by a net inflow of young children and old people. The explanation lies in the sharp decline in participation rates with school children staying longer in a school and with women getting married earlier and leaving the labour force.

The 1971 - 76 period was the poorest for non-agricultural employment growth as it included the 1974-75 recession when significant declines in non-agricultural employment were recorded. The total employment fell Non-agricultural employment is expected to increase by 23,800 per annum over the period. (It is assumed that the Government employment targets are based on the same official data as published in the Department of Finance Review and Outlook and that the 1980 target really refers to April 1981).

Agricultural employment is expected to decline by 4,000 a year so that total employment is expected to rise by an average of 19,800 in the five year period. The Government target is a 75,000 reduction in the numbers out of work over the period 1978 to 1980 - interpreted as April 1978 to April 1981 in the table. Thus average unemployment is expected to decline by around 16,800 in the five year period. This would imply a growth in the labour force of only 3,000 in spite of the sharp improvement in job opportunities. This is inconsistent with the labour force projections made by Brendan Walsh.

If one accepts that the labour force will grow by 9,000 a year then the reduction in unemployment, even on the assumption of very high growth rates for non-agricultural employment, will only fall by 10,800. This would be consistent with a 45,000 target reduction in the numbers out of work over the period 1978 - 81, in contrast to the Government's target of 75,000.

Of course, consistency is only one check on the plausibility of the Govern- ment projections. But a consistent fiction is still a fiction and the credibility of the Government projections depends very much on the assumed rate of growth of employment. The projected employment growth is twice that achieved in 1961 - 66; the best experience ever. It represents an annual average target higher than the level achieved in any one year in the past. Of course, it might be argued that the ten year aver-age from 1971 - 81 is only fractionally higher than the 1961-66 performance. But this assumes that the employment lost in the recession is recoverable, that the employment effects of the EEC have been negligible and that world economic conditions in the next few years will be such that world demand will be at a level as if the recession never occurred. This unlikely set of as-sumptions is responsible for the fact that most economists and businessmen have little confidence in the ability of the Government to meet their employment targets.

This is not to say that there are other, instantly available, policies which could do better. Nationalisation of productive capacity will not change the level of world demand, nor will it change the income sensitivity of the demand for imports. A siege economy approach, involving a withdrawal from the EEC, might guarantee full employment but it would do so at real incomes significantly below those at present enjoyed by the bulk of the population. Such a cure would be so drastic that it would suggest that full employment must be obtained at the expense of real incomes no matter how large the fall in the latter.

Presumably there is some trade-off. Thus the problem of unemployment can be overcome by ensuring that adequate income replacement is available for those without jobs, that schemes are available for those who are too long without jobs, that retraining is available for those whose skills have become redundant, and that educational and other social policies are geared to minimising the excess flow of labour onto the market. All this costs money and the real incomes of those in em-ployment will have to be reduced - or the growth in them slowed - to pay for it.

The continued unwillingness of politicians, trade unionists, businessmen, and the media to admit that there are no easy solutions, that there is no simple panacea to cure unemployment remains an obstacle to efforts to ensure that the social misery caused by unemployment is tackled by the Goverment.