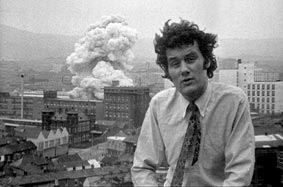

Man of war

Justine McCarthy talks to Kevin Myers about his memories of the Troubles in Northern Ireland and discovers that the Irish Independent columnist is capable of touching kindness, in private

He has been recounting his gruesome eye-witness memories of cold- blooded murders, gun battles, street riots and violent depravity for 55 uninterrupted minutes before the tears start to slide from Kevin Myers' alarmingly penetrating eyes. What has distressed him is not the image of a soldier's bullet lethally entering the cheek of a stone-throwing teenager as he talked to him on an Ardoyne street, or a UDA attempt on his own life in a south-Belfast pub, or the guilt of consciously failing to prevent the death of an ambushed soldier whose helmet local lads kicked around as a football while the body was still warm, or the eight killings he says he witnessed and the 40 funerals of friends and acquaintances he says he attended in seven years of covering the Troubles. Not Bloody Sunday or Bloody Friday or the anti-internment riots or the La Mon bombing or the massacre in McGurks Bar. What finally cracks his composure is his confession that he once deflowered a virgin called Brenda and, to make amends for breaking her heart, bought her a recording of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony.

Myers, the fearless, savagely-literate critic of bleeding-heart liberalism, is sitting skew-ways at his wooden kitchen table, the golden-copper light of an autumn morning illuminating a bucolic tableau of ancient tranquillity in the valley beyond his french windows. His coffee mug is perched on a luridly blue coaster declaring Elvis Lives. "I'm sorry," he says, fixedly facing the side wall where a wax coat is draped to dry over a clothes pulley. His embarrassment is as unexpected as his tears. "It's a terrible thing when you realise you've hurt somebody. One of the values I was brought up with as a Catholic was that you must never, ever hurt somebody."

Victims of his vicious penmanship – including "mothers of bastards", as his most abhorred column in the Irish Times categorised single mothers – might wonder about the descending hierarchy of his do-not-offend value system, but that's Kevin Myers, the infuriating, inflammatory paradox.

In print, he can be brutally outlandish while, in private, he is capable of touching kindness. He can be chivalrously lachrymose about shunning a woman he slept with 30 years ago but does not flinch in his denunciations of whole categories of strangers. The difference, one suspects, is that it is his own flawed behaviour he is lamenting in the case of Brenda, his smitten conquest and for that he, in part, blames the Troubles.

"Without that experience and those years, I wouldn't have become Kevin Myers," he proclaims. "This is going to sound a bit pompous but... I don't think I would have the moral authority to talk about Northern Ireland the way I do if I hadn't had that experience. I've been there."

Though he no longer wakes from nightmares in the middle of the night, he believes he returned "damaged" from his seven years in Belfast, working for RTÉ and later for Hibernia, the Observer and NBC in the US. He reckons too that he became addicted to violence. "I was a likeable, untroubled cheerful young man when I went up and when I left I had developed a really dark side. Yes, I was mad. I was drinking a calamitous amount towards the end. I recognise now that I would have been clinically diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome, but I've got over it. At times, I'm not a very nice person. There is a burden those years have put upon my soul. I knew people who had killed my friends. I drank with them.

"I wasn't a very good reporter. All I was doing was counting bodies. I was a young man who wanted to take risks. I did enjoy the thrill of violence. We got a charge from it – testosterone or whatever. Men like danger more than women but there's a small number of women who are addicted to it. I was going out on gun battles night after night after night. When you're young you can forget the really bad things associated with violence – that somebody was going to die. I was able to shove it aside and forget the personal consequences of these things that I was getting such a vicarious pleasure from. I didn't identify it as a disease until much later."

It took him two months to write Watching the Door, his 271-page memoir of his time as a Troubles reporter from 1971 to 1978. It reads like Hemingway on Viagra, an action- packed, melo-machismo orgy of bloodletting and bloodshedding punctuated by the author's sexual athletics or, as he describes them, "my endocrinal safaris". The jacket sleeve says it is "a coming-of-age book like no other" but it also serves as a reinvention of the author in one of his Shakespearian latter ages as an – if not the – elder statesman of the Fourth Estate's Troubles veterans. Such self-aggrandisement invites deconstruction from others who were there but it also explains why he was so furious at not being commissioned to write for the Irish Times supplement on the 90th anniversary of the Easter Rising this year that he quit and joined the Irish Independent as a columnist.

Bubbles of inconsistency float to the surface of several chapters. For instance, Leo McGuigan, the Ardoyne boy shot dead by the soldier, was aged 16; not, as Myers says in the book, 14. His claim to have arranged a meeting between the Provisional IRA and the UVF does not tally with other accounts previously published. An aside that he once overheard Gerry Adams issuing orders to kill a man jars with Myers' fierce loathing of the Provos, begging the question why he did not volunteer this incriminating testimony before. As he wrote the book without the benefit of either his contemporaneous reporter's notes or a diary (his only source document was David McKittrick's book, Lost Lives) how much of it is the novelistic embellishment and imaginings of a fantasist?

"I have been as scrupulous as I possibly can about life and death, about the deaths that I saw and the suffering that I saw. Whereas, dealing with the narrative of the non-violent knockabout things that I saw, some of that has been elaborated on. I cannot remember word for word what people said to me on a particular day but I have a reasonable memory. In the mid-'70s, I was a PhD in death. I knew all those killings. When I came across them again an entire catalogue of memories was prompted by the names.

"One of my problems is that I have a memory that is so stacked with events. I have an unusually retentive memory. It's both retentive and vibrant. I have a friend, Barney Cahill. I had lost contact with him and then he rang me recently. He's working class and a republican from Belfast. He doesn't agree with my politics at all. He said to me: 'Kevin, you're the only journalist I know who actually went to the heart of the Troubles.' I didn't live with other journalists, or socialise with them. I drank with the UDA, the IRA and the UVF."

According to his passport (reproduced in the book with his passport picture on the back cover capturing a curly-haired '60s free-love refugee), he had brown hair, blue eyes and an oval face. He describes his younger self as "very English in accent and manner", an outsider "made more so by my aloofness in manner, my supercilious speech". His personality, he admits in the book, "did not invite affection from the general student body" in UCD. He was born to Irish parents in Leicester, England 60 years ago next March and attended Ratcliffe boarding school where, "on a point of principle", deceased community members were laid out and the boys required to file past "to see what death was like". It proved an inadequate rehearsal for the worst years in Belfast.

On the night he saw Leo McGuigan die, he went back to RTÉ's office and announced: "It's mad in Ardoyne." He was told to go live without a script on radio. "I didn't put this in the book. I broke down on air," he recalls. "I didn't cry. The boy's face came back to me. I was there on my knees beside him. I froze. I had seen Private Malcolm Hatton [aged 19] shot dead the night before. I had been up since dawn. I had seen 20 or 30 gun battles. It got to me when I was doing the radio piece."

In Newry, covering a nationalist march, Myers independently calculated that the marchers amounted to about 25,000 people but other journalists arrived at a figure of 100,000 and so that was how many he too reported, not his own estimate. This, he argues, is indicative of journalism-by-consensus.

"Journalism disappoints me," he confirms. "Journalists subscribe to consensus without knowing it. It's not a political consensus defined by left-wing or liberal values. It's a series of values which journalists generally hold in common. They're values journalists discuss in pubs that make them feel comfortable. Any journalist who says, 'I like Michael McDowell,' is going to be sneered at because we don't listen to opinions we regard as being unusual. We want orthodoxy.

"Journalists, for instance, who would demand that a brain surgeon prove his credentials never challenge the credentials of people they call asylum seekers. Journalism warps history. That first draft has to be revised again and again and again. The sneer is a social tool. You see it repeatedly when interviewers become all huffy if someone voices an opinion that is outside the consensus. I don't think Ireland has changed much in terms of intolerance. The lynch mob is poised."

Whatever about sneers, chortles will greet some of the Carry On Up The Khyber scenes in his book. Like the night he went home with the wife of "a senior IRA man" and, hearing the husband's car pull up outside, clambered naked into hiding under the marital bed. When the Provo, a weightlifter, stripped for bed, the wife cajoled him into making her a cup of tea and, in his absence, our hero scarpered into an adjoining bedroom where the wife's sister was sleeping off a massive binge.

On another occasion, he went drinking in a south-Belfast pub with a loyalist called Dougie Big Eyes (code-named Sammy Flat Face in the book for legal reasons, "though we've found out since that he's dead"). There, he was introduced to the local UDA commander, Rab Browne, who quizzed him about the name 'Kevin' and whether he might be a Fenian. After four hours drinking with the men, his driver warned Myers that the guns had been sent for to kill him. He escaped from the bar and crouched on the far side of his driver's car, from which vantage point he heard two of the men emerge. "Ah fuck, he's gone," groaned one. Myers then made his escape running alongside the car as his driver steered it away.

In yet another cameo, he and his RTÉ colleagues took it in turns to dig a grave on the Black Mountain for the dearly departed wife of a fellow worker during a grave diggers' strike in Belfast.

He resigned from RTÉ in protest at the government's sacking of the RTÉ Authority after Kevin O'Kelly's famous radio interview with Sean MacStiofain. To his surprise, nobody else handed in their notice, despite copious pledges to do exactly that in solidarity with their jailed colleague, O'Kelly. Asked if the national broadcaster protected its people working in the North, he replies: "There was a negligence about our welfare which, in retrospect, was quite scandalous. News desks are run by people who've never been in action. They haven't got a fucking clue. There was no concept of duty of care. The concept didn't exist in those days."

From the house he shares in rural Kildare with his wife, Rachel ("my rock and my love at all times"), and their eight dogs, you can see Mount Leinster 40 miles away on a clear day. Closer to the house, lands owned by Barretstown Castle roll luxuriantly towards the horizon. Through a window on the other side of the kitchen, a horse's nose bobs over a half-door in the stable yard. The contrast with Belfast in the 1970s could not be starker.

Kevin Myers comes outside to see off the visitor. "By the way, why the title, Watching the Door?"

"Watching the door," he answers, "waiting for death."

And he waves goodbye.