Made in Mayo

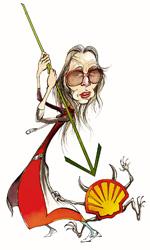

Maura Harrington, one of the Shell to Sea campaign's leading personalities, has rallied against Margaret Thatcher, the EU and, now, against the Corrib gas pipeline. Justine McCarthy profiles the mother of four from Erris who won't give in to the oil industry.

On Christmas Day 1984, a young mother unwrapped her Yuletide present from her husband in their Gaeltacht home overlooking the thrashing Atlantic and beamed with pleasure. Her gift was a money donation to the British miners' strike fund. Earlier that year, she had raised stg£500 for Arthur Scargill's protracted swansong showdown with Margaret Thatcher's capitalist agenda by running a raffle in Mayo. First prize was a bronze figure of a coal miner. Two decades later, her zeal for confronting industry's lucrative interests has not diminished. Maura Harrington's slight, crinkle-haired, swift-moving figure strides the national stage. Depending on whether one sympathises with the Goliath of the Shell/Statoil/ Marathon consortium or with the David of the Rossport Five, the incessantly-smoking, gaelgóir mother of four and school principal is either a feisty heroine or an anti-progress dervish concealing sinister political connections.

The image of her prone and wrapped in blankets on the road outside Shell's burgeoning refinery at Bellanaboy, in the throes of a confrontation between protesters and massed gardaí on Friday 13 October incensed both sides in the €8bn argument. Protesters remonstrated that it was further proof of a police state that had turned against its own citizens. Shell and its supporters saw it as a stunt to jerk the heart-strings of ambivalent onlookers. Self-professed eyewitnesses on both sides have given conflicting accounts of what happened. The woman herself says she intends suing the State for damages as a result of the incident.

"I was in the frontline," she recalls. "We were walking towards the oil roads, on the main road. We saw the guards coming forward. The next thing, I was literally flying through the air. I don't remember how it actually happened. I landed on my head on the tarmacadamed road. No guard has taken a statement from me about it."

Harrington, who is on leave from the five-teacher scoil náisiúnta an Inbhir, where she has taught for 34 years, describes her personal political ideology as being on the "Connolly-ite end" of the socialist spectrum. "I am not a card-carrying member of anything," she said, while recovering at home from her head and neck injuries. "I adhere to the Mayo colours – the green and red – and I'd be broadly Marxist in an economic sense. It translates into how economics are subverted in the name of what's called progress.

"At the first rally we had in Castlebar after the Rossport Five were jailed last year, I said on the platform that day that we were not politically beholden to anybody. We accept support from the far right to the far left because it's an issue that affects everybody."

In its simplest interpretation, the north-Mayo stalemate is an issue of health and safety. Local people living near the proposed route of the pipeline that will transport unprocessed gas 80 kilometres ashore from the Corrib sea-bed to the wildly beautiful Erris peninsula are literally scared for their lives.

The broader, more layered and more divisive debate is between the forces of multimillion-dollar globalised industry and the physical and cultural integrity of a people and their place. By its nature, that debate has attracted two motley crews of agitators. Shell – accused of offering bribes to certain people in the community for their support – has the backing of corporate Ireland, the government, state authorities and some local business people who expect the pipeline to provide an economic lifeline for Mayo. The objectors – accused of inciting a mood giving rise to death threats to marine minister Noel Dempsey – include local people with genuine safety fears, some backbench Dáil deputies, some environment academics versed in the potential dangers and a mixum-gatherum of anti-globalisation anarchists with diverse party-political allegiances. The Workers' Solidarity Movement, for instance, has a strong presence in the campaign, but so too has the Independent Mayo TD, Jerry Cowley. When he and three other Independent TDs visited the protest in solidarity, they were video-recorded by gardaí.

"If Shell had known there was a woman in Erris called Maura Harrington, they'd have brought their gas in somewhere else," suggests one of her admirers. "That woman is never going to give in to them."

But for a twist of fate, she might have proved an even more formidable opponent. Upon leaving the Jesus and Mary order's Gortnor Abbey boarding school in Crossmolina in 1970, she was offered a place studying marine biology at UCD. Destiny, however, took her to Carysfort College in Dublin for two years' national-teacher training. Her mother, Mary Sweeney, had graduated from UCG as a secondary teacher in the 1940s and taught in London before her marriage to a Mayo coastguard's son, John Harrington.

As the eldest of three children growing up in Doohoma beside Blacksod Bay, Maura Harrington developed a deep respect for her county forebear, Michael Davitt, and inherited her appetite for justice from her late father, whom she describes as "a fitter and an egalitarian". At the age of 19, she read four books that would influence her for the rest of her life – Sartre's Roads To Freedom trilogy and Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee, a history of the American Indians by Dee Brown.

In the 1990s, she railed against the Maastricht Treaty because she suspected that the carrot of EU largesse was greatly exaggerated and that the new single European market would impose detrimental changes on her beloved Mayo. She campaigned against the referendum on behalf of the National Platform, run by Trinity College academics Anthony Coughlan and the late Raymond Crotty.

After that battle was lost and the referendum was carried, she faded from the political scene. Then, one day in the summer of 2000, the mother of four (her children are now aged from 18 to 24) spotted a notice pinned up in her neighbourhood supermarket announcing a public information meeting about Shell's plans for the Corrib gas. Harrington went along with a list of prepared questions. Her final one wondered if the petroleum multinationals intended using Irish workers to construct their facility. She has not slackened since.

"We're tough, the Erris people. This is about preserving the integrity of this place that has been preserved for 5,000 years. That's attested to in its place names and its way of life. Those backing the pipeline say this is about progress but, when you're moving in a continuum, you don't move to anywhere other than where you are. That's the defining thing with the whole pipeline."

On the anniversary last year of Davitt's founding of the Land League, 16 August, she launched the Davitt League in the same room of the same building, the Imperial Hotel in Castlebar. It is affiliated to the People Before Profit Alliance, a 32- county "people power" anti-globalisation movement established by the Socialist Workers' Party. Harrington says the People Before Profit Alliance has asked her to be its candidate in next year's general election but that she has declined because she is a single-issue campaigner, and that campaign is Shell to Sea.

"The shits-in-suits dismissed us as a shower of bog-trotters when they moved in and that disdain will always stay with me," she says. "This campaign is ego-less and non-hierarchical. It's just the right side of obsessive. People don't veer away and take up some other issue. There's no dilettantism. My father was an egalitarian and so am I. Strong women are a feature of Erris."