The Life and Irish Times of Douglas Gageby

How Dublin's most celebrated editor brought his newspaper back from the dead twice: the politics, the rivalries and the drama of the Irish Times' survival.

Writing of his trade, veteran journalist James Cameron admitted, ''We journalists spend our time splashing in the shallows, reaching on occasions the rare heights of the applauded mediocre." He added, "It looks, perhaps, easier than it is."

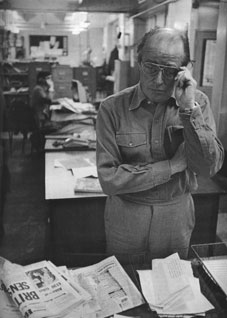

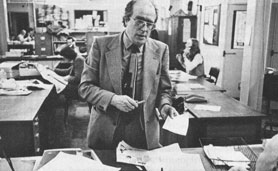

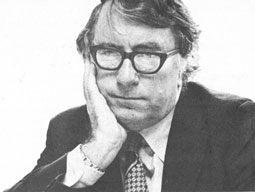

In a trade where hyperbole is the norm the applauded mediocre is all too common and few figures are accorded any measure of respect unalloyed with cynicism. Douglas Gageby, after twenty years' association with the Irish Times, is one of that few. Journalists on his staff, some with political and social views quite divergent from Gageby's, unashamedly declare themselves to be "fans" or "admirers". Fergus Pyle, who replaced Gageby as editor of the paper for three lean years, and who might be expected to be bitter about his own unceremonious dumping after Gageby made his way back to the editorial chair, displays nothing but admiration. Tim Pat Coogan, editor of the Irish Press, declares his rival to be "the outstanding editor of his time."

The statistics are there to substantiate the plaudits. In his first decade as editor Gageby doubled the circulation of the Irish Times. More significant was the method he used to do so, bringing the paper away from its peripheral role as the voice of a fading Protestant ascendency and on to the centre of the journalistic stage. Soon after Gageby resigned as editor in 1974 circulation went into a tailspin and for a time the future of the paper was in doubt. Immediately following Gageby's return to the editorship in 1977 circulation spiralled upwards, surpassing even his earlier achievement.

The statistics are there to substantiate the plaudits. In his first decade as editor Gageby doubled the circulation of the Irish Times. More significant was the method he used to do so, bringing the paper away from its peripheral role as the voice of a fading Protestant ascendency and on to the centre of the journalistic stage. Soon after Gageby resigned as editor in 1974 circulation went into a tailspin and for a time the future of the paper was in doubt. Immediately following Gageby's return to the editorship in 1977 circulation spiralled upwards, surpassing even his earlier achievement.

If Gageby was the engine which powered the Irish Times in its triumpharit progress, the road on which it travelled was thrown up by the shifting ground of Irish social developments. While Gageby's talents are undoubted he also encountered an extraordinary amount of luck. Paraphrasing James Cameron, it looked, perhaps, simpler than it was.

The Voice of Southern Unionism

Douglas Gageby began his association with the Irish Times in the paper's centenary year, 1959. The standard joke in the newsroom in that period was to check the number of items in the "Deaths" column in the first edition as it came off the press. If there were ten, for instance, the joke went that while yesterday's circulation figures might have been 33,000 today's would be 32,900. Many of the journalists were aware that they were writing for a dying class.

The Irish Times and Daily Advertiser was founded in June 1859 by Major Lawrence Knox, a member of Isaac Butt's Home Rule movement who described himself as a Conservative Nationalist when he stood for election at Mallow in 1870. The paper from the beginning included a business page and was aimed at the business and professional classes. It was later bought by Sir John Arnott and became a public company in November 1900.

From 1907 the paper was under the editorship of John Edward Healy. Fiercely pro-British, stern and inflexible, Healy edited the paper for 27 years, holding the Unionist flag aloft in the face of the advancing nationalists and the paper maintained its pro-British, pro-business line throughout the tumultuous events surrounding the founding of the Free State. The IrishTimes quite deliberately assumed the role as the voice of Unionism in the decade that followed and when it used the terms "the Army, "the Government" or "our Prime Minister", it was referring to those institutions in Britain.

Without falling into the camp of the Free Staters the paper vehemently opposed de Valera in the 1932 election, citing "the need for self preservation" in the face of what appeared to be, and what subsequent events disproved to be, rampant republicanism. "If Fianna Fail takes office," said the Irish Times, "the Free State's carefully fostered prosperity will wither, and she will become an Ishmael from that Empire which the ex-Unionists, their sons and their ancestors have helped to mould."

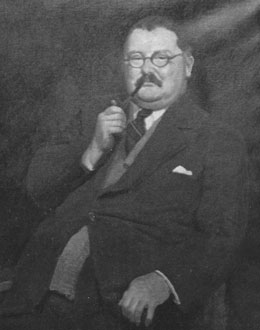

The Unionist tradition was maintained by the flamboyant Bertie Smyllie, who took over as editor on Healy's death in 1934. Smyllie, with his broad-brimmed black hat and silver-topped cane, was an extravagant, theatrical figure most at home amid a coterie of hangers-on in the Palace Bar. In his book Head or Harp a one-time leader writer Lionel Fleming described the late-night scene in the newsroom, with Smyllie correcting proofs with one hand and using the other to play dominoes with Alec Newman, while at the same time regaling the reporters with blue lyrics sung to the melody of Beethoven's Choral Symphony. Smyllie's allegiance lay with what he called "the red, white and shuddering blue", and Fleming related the following piece of dialogue as an example of where the Irish Times stood politically.

"Mr. Newman!"

"Mr. Smyllie, sir?"

"It will not have escaped your attention, Mr. Newman, that the British forces on the north-west frontier of India have conducted a successful and well-merited aerial offensive against the dissident wogs up there. A leading article justifying their action, if you please."

Despite such jingoism Smyllie was well aware that the clock could not be turned back. His was a Dublin paper and its Protestant constituency did not include the bulk of the upright Loyalists in the North. It accommodated to the realities of the Free State and in doing so found a niche between the pious Fine Gaelism of the Irish Independent and the triumphalist Fianna Failism of the Irish Press. While those papers carried the flags of the political parties which they respectively supported and wore proudly the sash of the Catholic Church, the background and traditions of the Irish Times dictated that it remain politically unaligned, its unionist flag waving ever more limply as the years went on, and its social attitudes antipathetic to those of the rampant Catholicism of the time.

Even under Healy the Irish Times had, at first tentatively and then with determination, raised a note of opposition to the enshrining of Catholicism in the laws of the state by supporting the right to divorce and by consistently editorialising against the 1929 Censorship of Publications Act. This Act led to a stifling effect on literature and prohibited the publication of information about birth control. The Report of the Committee on Evil Literature, on which the Act was based, was described by the Independent as "a model of moderation, good sense and brevity".

Even under Healy the Irish Times had, at first tentatively and then with determination, raised a note of opposition to the enshrining of Catholicism in the laws of the state by supporting the right to divorce and by consistently editorialising against the 1929 Censorship of Publications Act. This Act led to a stifling effect on literature and prohibited the publication of information about birth control. The Report of the Committee on Evil Literature, on which the Act was based, was described by the Independent as "a model of moderation, good sense and brevity".

When the Spanish Civil War erupted in 1936 the Independent, predictably enough, raised the Catholic flag and sent a reporter to the fascist side. Smyllie immediately put a proposition to Lionel Fleming. "You say you've got no money for a holiday. Give you fifty pounds and go down on the republican side. I don't give a bugger what your conclusions are, as long as you're honest."

Fleming's reports drew Catholic ire and the paper's advertising revenue was threatened.

By the mid-1940s the Irish Times had broadened its readership to include those Catholics who found the other papers too shrill, partisan or pious. Owing no debt to nationalism it was less insular, owing no debt to the Catholic establishment it could be critical. It became the paper of the intellectuals and academics, regardless of religion or politics. Although not liberal in itself it became the national focus for what liberalism survived the stifling social attitudes of the time.

The Irish Times' unionist reputation brought the paper under suspicion during the Second World War. The censorship which was applied to all papers was redoubled in the case of Smyllie's paper and every single inch of copy, including advertisements, had to be submitted to the censor. The paper was not allowed to describe even factual events occurring in the conflict and all mention of military rank and military causes of deaths and injuries was forbidden. A former Irish Times staffer who was wounded in action was described as having received "lead poisoning". Smyllie's anti-neutrality views occasionally slipped through. On the last day of the war in Europe he as usual submitted a copy of the paper to the censor. It escaped the official's notice that the numerous small photos on the front page, illustrating various inoccuous social events, were arranged in the shape of a V for victory.

While the Irish Times was being muffled by the blanket of the State its future editor was enjoying his first gainful employment within an arm of that state. Douglas Gageby served during the war years as a second lieutenant in Military Intelligence. In that period the de Valera government was involved in continuing conflict with the IRA, the internment camps were open, and the military tribunals directed the execution of several IRA men brought before them. The German Abhwer was sending agents to Ireland to exploit the situation and Gageby, who had joined the army as a private on the outbreak of the war and who had acquired a degree in modern languages at TCD, was brought in to Intelligence on the basis of his command of German.

Robert John Douglas Gageby was born in Dublin in 1918. His grandfather, Rogert Gageby, a Shankill Protestant, had gone to work in a mill at the age of 11, become secretary of the flax dressers' union and was one of six trade unionists to win a seat in the Belfast municipal elections of 1898, with Independent Labour Party support. Determinedly non-sectarian, Robert Gageby remained a Belfast Councillor for twenty years, and when he stood as a Labour candidate in the 1910 general election he received almost 4,000 votes, just 2,000 short of the Conservative candidate, despite Belfast Telegraph editorialising that Gageby's election would mean the break-up of the Union.

Robert Gageby's son, Thomas, left Belfast to escape the poverty and sectarianism and took a job as a minor civil servant in the South. He returned North with his family in 1922 to take a job with the new Unionist regime, which was seeking experienced civil servants, and his son Douglas returned to Dublin in 1936 to study at Trinity. After his parents died during his stay at the College Douglas Gageby decided to stay on in Dublin.

Although he had not dabbled in student journalism while at TCD, Gageby had decided on a journalistic career and while in the Army wrote some pieces for the Irish Press. The wartime paper scarcity meant that being published in the four-page paper was an achievement in itself and before Gageby left the Army in 1945 he wrote to the Irish Press seeking and getting a job as a junior sub at four guineas a week.

His subsequent rise was swift. Within four years he became assistant editor of the Sunday Press and three years later, in November 1951, was appointed editor-in-chief of the Irish News Agency. This had been set up by Sean McBride, who was Minister for External Affairs in the Interparty Government, with the aim of establishing an agency which would keep available to foreign media a constant flow of hard news from Ireland.

Conor Cruise O'Brien, then a civil servant, was made managing director of the INA almost by default, there being, apparently, no one else around who would take the job. The INA had a strong team of reporters, including such people as John Healy, Michael Finlan and Gerry Mulvey whose paths would again and again cross Gageby's. However, the agency folded after about six years when it became clear that the Irish Independent group was not interested in joining with the other newspapers to fund and run the project independent of the government, in line with McBride's original idea. The INA also came under attack from editors and news editors who feared that the Agency would undermine their lucrative sideline of selling to British papers the stories gathered by their own reporters. By then, Gageby had moved on, in 1954, to edit the new Evening Press.

Within six weeks of the establishment of the Evening Press Gageby had a circulation boosting story on his hands, the famous "Missing Babies" saga. The story broke in the run-up to Christmas and Evening Press reporters were instrumental in the recovery of one of the three kidnapped children, giving them an edge over their rivals, the Herald and the Mail. The Evening Press was printing at noon in an effort to outstrip its rivals, which went to press after 3 pm, and teletype machines were installed at a number of sub-stations around the country in order to update the paper as it was distributed. Gageby's lively news sense, his excellent eye for pictures and layout, and his possession of what a contemporary called "the common touch, with quality overtones" helped the Evening Press and sales leaped ahead. By the time Gageby left, five years later, the Press daily sales had passed the 100,000 mark and the paper was well on its way to becoming the top-selling evening paper.

The leaning towards republicanism which Gageby was to display in later years at the Irish Times was well buried in those days. It seemed almost as if he was making a deliberate effort to keep the Fianna Fail image of the Irish Press from spilling over onto the evening paper. He leaned, as a fellow Press journalist put it, "more towards the Archbishop than the altarboy", The "popular but quality" touch led to the hiring of J. Ashton Freeman, who for years wrote an avuncularly informative column on nature and wild life. Similarly, John Healy was dispatched to the amateur drama group beat. At that time there were approximately 750 such groups throughout the country and the coverage was aimed at improving provincial sales among the considerable constituency of the groups' members, friends, relatives and audiences, while at the same time giving the paper a touch of popular culture. A Lieutenant Thomas O'Faolean, an acquaintance from the army days and then working for the tourist board, was brought in to write a social column and the reception-riddled career of the pseudonymous Terry O'Sullivan was begun.

In 1959 Gageby was approached by George Hetherington, managing director of the Irish Times, with an invitation to bring his talents to the ailing paper as managing editor. When taking up his position with the Evening Press in 1954 Gageby had told Vivion de Valera, the Press Group chief, that he would stay for only three or four years. Yet he at first rejected the Irish Times offer. He didn't feel it was his kind of newspaper. He told Hetherington he didn't like the politics of the Irish Times and wouldn't take the job unless he could have a position on the Board, where he could influence policy. A few months later Heatherington returned with an offer of a directorship and Gageby made the move.

In 1959 Gageby was approached by George Hetherington, managing director of the Irish Times, with an invitation to bring his talents to the ailing paper as managing editor. When taking up his position with the Evening Press in 1954 Gageby had told Vivion de Valera, the Press Group chief, that he would stay for only three or four years. Yet he at first rejected the Irish Times offer. He didn't feel it was his kind of newspaper. He told Hetherington he didn't like the politics of the Irish Times and wouldn't take the job unless he could have a position on the Board, where he could influence policy. A few months later Heatherington returned with an offer of a directorship and Gageby made the move.

Gageby became joint managing editor of the Irish Times, along with George Hetherington, in the same year that Sean Lemass became Taoiseach. Fianna Fail's First Programme for Economic Expansion had been published the previous year and a decade was about to begin in which the economic foundations of the state were to be drastically altered. Also in 1958 the Protection of Manufacturers Act was repealed. Successive governments had vainly attempted to encourage a native capitalism, but by the 1950s the home-based economy had reached the limits of its capabilities and was beginning to run down. Between 1951 and 1962 total employment dropped by 164,000 and throughout the 1950s emigration was at an annual rate of about 40,000.

The reversal of policy, which opened up the economy, offering incentives to foreign companies, bringing the Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement in 1965, and eventually membership of the EEC, brought massive social changes in its wake. Irish capital had failed and just as the economic barriers had to be taken down to give international capital free reign so the Green Curtain had to be drawn back in order to adapt the population to the new economic regime. The establishment of a national television channel in 1961 played a large part in starting that process. In addition, the paperback explosion and increasing opportunities in education gave wider access to information. Increased prosperity (in the period between 1960 and 1966 profits rose by 54 per cent) brought a mood of militancy to the unions and social expectations were raised as workers fought throughout the tumultuous decade for a share of the growing cake.

The Irish Times was in a unique position to take advantage of these changes. Whereas the Press and Independent could complacently rely on the continuing support of their respective shares of the Fianna Fail-Fine Gael readers, the Times had no comparable natural constituency. While the paper still had a firm hold on the allegiances of business people, politicians, civil servants, intellectuals and academics, the decline of the Southern Protestant Ascendancy demanded that the Times take steps to widen its roots among newspaper readers. At the beginning of the 1960s its circulation ranged between 33,000 and 35,000, about one-eighth the combined circulation of the Press and Independent. Neither of these papers had any need to hustle for readers and they were far slower than the Irish Times in responding to the changes in society. As a consequence in the period between 1964 and 1974, while the daily circulation of the Irish Times was rising by 34,000, the circulation of the Independent fell by almost 8,000 and that of the Press by a massive 36,000.

Just Pottering Around

Before Gageby assumed editorial control of the paper he had to undergo four trying years, from 1959 to 1963, as joint managing editor, a largely administrative position. Irish Times Ltd., in an attempt to diversify and create a stable of newspapers analogous to the Press and Independent groups, had started the Sunday Review and bought the Evening Mail. Both were financial disasters and almost brought the company into bankruptcy. The Sunday Review was a brash tabloid that was before its time. Gageby experimented with colour printing and there was an attempt to procure the rights to the sort of colour comic strips which now run in the Sunday World, but failed for technical reasons. Unlike the World, the Review carried a lot of hard news and fairly weighty political reporting. When it folded all of its writers were hired by other publicatIons within a couple of days. If the Review had received advertising support (the new TV service was drawing the advertisers) it would have survived and the Sunday World might never have been born.

Before Gageby assumed editorial control of the paper he had to undergo four trying years, from 1959 to 1963, as joint managing editor, a largely administrative position. Irish Times Ltd., in an attempt to diversify and create a stable of newspapers analogous to the Press and Independent groups, had started the Sunday Review and bought the Evening Mail. Both were financial disasters and almost brought the company into bankruptcy. The Sunday Review was a brash tabloid that was before its time. Gageby experimented with colour printing and there was an attempt to procure the rights to the sort of colour comic strips which now run in the Sunday World, but failed for technical reasons. Unlike the World, the Review carried a lot of hard news and fairly weighty political reporting. When it folded all of its writers were hired by other publicatIons within a couple of days. If the Review had received advertising support (the new TV service was drawing the advertisers) it would have survived and the Sunday World might never have been born.

The Evening Mail made a vain attempt to survive by going tabloid but it too went to the wall. Ironically. Gageby had helped to kill his own paper. While the Herald held its own, the Mail collapsed in the face of the continuing success of the Evening Press. Gageby today describes his role in those first four years with the Times as "just pottering around". It wasn't until October 1963 that he left his administrative job and succeeded Alan Montgomery as editor of the Irish Times.

The paper had maintained its independent stance during the 1950s, editorialising against book censorship and, in April 1951, was instrumental in exposing the craven obedience of the politicians to the Catholic bishops at the time of the Mother and Child Scheme controversy. Without the Irish Times' willingness to publish the correspondence between politicians and clergy it is doubtful if the extent of clerical intervention in political and social life would have been revealed at that time. Alec Newman, who had succeeded Bertie Smyllie as editor in 1954, maintained the Times tradition of independence but did not have the same thrust as Smyllie. Alan Montgomery became editor in 1961. A former news editor of the paper, and editor of the Evening Mail for a period, Montgomery sharpened the news reporting but made no substantial change in the direction of the paper. In his eighteen months in the editorial chair he never wrote a leader. In a centenary issue in 1959 the Irish Times gave an accurate enough picture of its own ability, down through the years, to adjust to changing circumstances:

"During the many years when it was the recognised organ of Unionism it made no apology for the fact: it believed in the Union, and spoke fearlessly in defence of the Union. When the cause of Unionism manifestly was doomed, it turned its energies to the reconcilliation of Ireland's aspiration for freedom with the new conception of the British Commonwealth. When this hope faded, too, the, Irish Times accepted the fact and had given itself with the same enthusiasm to the advancing of a Republican nation."

Now, in 1963, with Douglas Gageby firmly in the editorial seat, the Irish Times was ready to make yet another adjustment. In 1962 Major Tom McDowell had taken over as managing director (a role he would maintain, under various titles up to the present). McDowell convinced the Board of the company to spend its way out of the crisis and to give Gageby a free hand on editorial matters, whatever the consequences. Looking every inch a retired major (and referred to by everyone simply as "The Major"), McDowell is aware of the incongruity of his Raj image and is sometimes inclined to play it up. Over the years, however, he has taken an almost paternal interest in protecting the paper's liberal image.

The company's financial problems, stemming from the Review and Mail fiascos, remained throughout the 1960s, being aggravated by a 13-week printers' strike in 1965, and it was not until towards the end of the decade that McDowell could breath easily. Meanwhile, the inffuence of Gageby was bringing the paper's circulation into a steady climb.

Hiring the Talent

Even at the beginning of the 1960s it was not unusual to hear a group of journalists being introduced as the "reporters" from the Press and Independent and "the gentleman from the Irish Times". In London the paper's office had a staff of three, headed by John Arnott (a descendant of Sir John Arnott, who bought the paper in 1900, and later to be knighted himself). The trio's main task was the compilation of a daily "London Letter", designed to keep readers informed of what was happening at the heart of the Empire. The junior of the three, Donal Foley ("the only commoner in the office"), recalled later in his book, Three Villages, how a cry of "A day for the whip, Arnott, what!", would propel the future Sir John to his typewriter to spew 1200 words of rage against the latest London dockstrike.

In Septemeber 1963 Foley received a visit from Major McDowell and an offer to return to Ireland as news editor of the paper. Foley had emigrated from his native Waterford in 1944 to escape the drudgery of unloading bales at a railway station. He held several labouring jobs before gaining casual work with the London office of the Irish Press, and after a few years on staff there moved to the Irish Times. His father had stood as a Labour candidate in Waterford in the 1932 General Election and Foley was a Gaelgoire who tended towards sympathy with the underdog. He had also been away from Ireland for almost twenty years and seemed at first an unlikely choice for the job.

In Septemeber 1963 Foley received a visit from Major McDowell and an offer to return to Ireland as news editor of the paper. Foley had emigrated from his native Waterford in 1944 to escape the drudgery of unloading bales at a railway station. He held several labouring jobs before gaining casual work with the London office of the Irish Press, and after a few years on staff there moved to the Irish Times. His father had stood as a Labour candidate in Waterford in the 1932 General Election and Foley was a Gaelgoire who tended towards sympathy with the underdog. He had also been away from Ireland for almost twenty years and seemed at first an unlikely choice for the job.

Back in Dublin, Gageby's first move was to get the reporters out of the office. Previously, politics was what happened in the Dail or the House of Commons and if social issues were to be covered it was in the context of what politicians or other eminent personages were saying about them. Now the journalists were beginning to go out on the streets to make contacts at less eminent but more informed levels. One of the more fruitful of these expeditions was Fergus Pyle's week in Derry, which was to pay dividends later on. Special correspondents were appointed on the theory that a single journalist assigned to a subject would gain a reputation for expertise and so would attract tips and leaks more readily. Subjects such as education, religion, industry, agriculture and diplomacy, previously dumped in the tray of a jack-of-all-trades political correspondent, were farmed out to individual journalists.

Conditions were improved, with the constant pushing of NUJ representative Michael McInerney, and the Irish Times was the first newspaper to drop the old "grace and favour" method in favour of a non-contributary pension scheme. Senior correspondents' salaries were pushed up by £500, a ploy to woo the best writers at a time when journalists would change papers for a much smaller increase.

Given a free hand by Gageby, Donal Foley played the major part in drafting the talent which made the paper shine in the second half of the decade. Foley's first criterion was that the recruits could write well and have an interest in the issues of the day. Formal journalistic experience was not a priority. Maeve Binchy was a former teacher, Mary Cummins a nurse. Mary Maher walked into the office, with four years experience doing routine reporting on a Chicago paper, immediately following a discussion between Gageby and Foley on the need to hire another female reporter. She walked into the job and began in November 1965.

Gageby's support for the hiring of a substantial number of women journalists derives from an attitude which is old-fashioned in its origins yet progressive in its effect, he simply believes that women are more sensitive, perceptive and accurate in their reporting. Whatever the basis for this attitude, the women hired, notably Nell McCafferty, Mary Maher and Maeve Binchy, were to produce some of the most sensitive, perceptive, accurate and stimulating journalism of that era. Prior to 1966 women's journalism in Ireland revolved around fashion, home tips and cooking and any excursion outside those areas was merely that, an excursion.

One of those excursions was by Ida Grehan, who wrote an article on the then new Ballymun housing estate. Out of ignorance and innocence, rather than malice, Grehan used the phrase "the poor we will always have with us". On the evening after the article appeared a housing protest was taking place outside the GPO and one of the demonstrators used the article and that phrase as an example of the establishment attitude to the housing crisis. Foley and Maher, incensed that the paper should display such insensitivity, complained to Gageby who shot back at Maher, "Why don't you edit a women's page?"

Maher was at first hesitant about the idea but went ahead to edit "Women First", a half page feature five days a week. The women journalists had freedom to explore issues of their own choosing on three of those days and even on the other two days, when fashions and food were mandatory subjects, they were free to investigate the social aspects of prices, value and consumerism. Over the next few years McCafferty and Maher were to play significant roles in the founding of the women's movement in Ireland. Later on, McCafferty's "In the Eyes of the Law" series, which relentlessly exposed the pitiless, mechanical, unjust and class-ridden court system, was a major breakthrough in court reporting.

It was after 7 pm and news editor Gerry Mulvey was unsure whether he should print the "crim con" story. A freelance photographer was claiming damages because his wife had had sex with another man, criminal conversation. "It's too long", said Mulvey, "and anyway, the law is being done away with." Deputy news editor Jack Fagan thought the story should run: "It's a good read". Donal Foley was called over. "Scrap it, we shouldn't touch it, it's a bloody ridiculous law, unconstitutional, it's going to be the last of these cases, anyway." On his way through the newsroom, Gageby joined in. "If Mary Maher was here she'd say we should run it, it shows the antediluvian nature of the law." And, Gageby agreed, it was a good read. "If we mention it at all," argued Foley, "it should be in a leader, saying that it's about time the law was scrapped." Gageby, without seeming to impose a decision, had the last word. The story would run, and if it got boring the paper would just give it a one-paragraph mention during the rest of the week.

It was after 7 pm and news editor Gerry Mulvey was unsure whether he should print the "crim con" story. A freelance photographer was claiming damages because his wife had had sex with another man, criminal conversation. "It's too long", said Mulvey, "and anyway, the law is being done away with." Deputy news editor Jack Fagan thought the story should run: "It's a good read". Donal Foley was called over. "Scrap it, we shouldn't touch it, it's a bloody ridiculous law, unconstitutional, it's going to be the last of these cases, anyway." On his way through the newsroom, Gageby joined in. "If Mary Maher was here she'd say we should run it, it shows the antediluvian nature of the law." And, Gageby agreed, it was a good read. "If we mention it at all," argued Foley, "it should be in a leader, saying that it's about time the law was scrapped." Gageby, without seeming to impose a decision, had the last word. The story would run, and if it got boring the paper would just give it a one-paragraph mention during the rest of the week.

The awakening women's movement was just one of the issues reflected in and supported by Gageby's Irish Times of the 1960s. Earlier on, Michael Viney had begun a series of investigaive pieces on unmarried mothers and on the aged. Eileen O'Brien was writing on such issues as poverty and Mary Maher's first assignment was to report on Artane Boys' School. Fresh to Irish society, she wrote an unblinkered and even naive expose of conditions. A slew of young students, including Conor Brady, Henry Kelly, Conor O'Cleary and Michael Heany, were recruited by Foley and brought a freshness and enthusiasm to the reporting. John Horgan was education and religious correspondent and there wasn't a dissident cleric within reach who wasn't invited to write for the paper. Pope John's reign had stated in 1958 and the Second Vatican Council had begun at the end of 1962. The world-wide debate within Catholicism about the need to adapt in order to survive coincided with and encouraged the increasing frustration with the paternalism and rigidity of the Irish hierarchy. For months on end tbe Irish Times printed long reports on the debate and itself became a forum for the controversy. Foley's influence led to the hiring of three Irish language columnists.

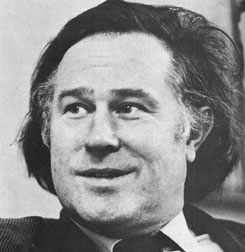

The same economic forces which were causing social changes in the Republic in the 1960s were also causing a change in the relationship between the Republic and the North, symptomatic of which were the meetings between Lemass and O'Neill in January and February of 1965. Gageby's decision to send Fergus Pyle to Belfast, as Northern editor, was not a conscious appreciation of that change but a reflection of it, a belief that for too long the North had been reported as if it was another country.

Prior to Pyle's assignment to Belfast the Irish Times had simply published news reports supplied by Bertie Sibbett, a stringer who worked for the Belfast Telegraph. The paper's office there was used largely to seek advertising. Neither of the other Dublin dailies carried any more than occasional straight news stories, similar to those supplied by local correspondents in remote areas, and more often than not the reports gave just one side of the story. A regular column written by Jimmy Kelly, an Independent journalist who had been reporting the North since the early 1930s, was not carried in the Southern edition of the Sunday Independent. Pyle had made contact with several sources during his sojourn in Derry four years earlier and these were now to prove fruitful. He also made contact with many of the students at Queen's University who were to become increasingly involved in the civil rights arena.

Pyle covered news stories as they occurred but also began giving consistent coverage two or three times a week to the intricacies of Stormont. Gageby's attitude, that "it's happening and that's why we're reporting it and if people don't want to read it that's all right", brought a certain amount of scoffing, The reaction of Bill Henderson, proprietor of the Belfast Newsletter was, "You're off your head". There was criticism that the reporting was overdone. For instance, when Bill Craig was fired by Captain O'Neill in 1968, Pyle sent down a 13 column report (at about a thousand words per column) and it was all printed.

In the event, the investment more than paid off. When the changes made necessary by economic forces came into conflict with the sectarian structures which had preserved the Unionist regime and all hell broke loose, the Irish Times had a huge head start over the other Dublin papers and reaped the benefits. Several reporters were sent North for periods to support Pyle and it took the other papers several years to catch up. During Pyle's stint in the North, from 1967 to 1970, if you wanted to get an idea of what was happening, and why, you read the Irish Times. During that period the paper's circulation rose by over 9,000. At the same time the Independent and Press each dropped almost 5,000 copies per day.

In the event, the investment more than paid off. When the changes made necessary by economic forces came into conflict with the sectarian structures which had preserved the Unionist regime and all hell broke loose, the Irish Times had a huge head start over the other Dublin papers and reaped the benefits. Several reporters were sent North for periods to support Pyle and it took the other papers several years to catch up. During Pyle's stint in the North, from 1967 to 1970, if you wanted to get an idea of what was happening, and why, you read the Irish Times. During that period the paper's circulation rose by over 9,000. At the same time the Independent and Press each dropped almost 5,000 copies per day.

The extent to which Gageby's republican leanings had changed the policy of the paper can be gauged from the following 1969 leader, commenting on a People's Democracy march: " ... to young people the border is more and more an irrelevancy ... a united Ireland would bring much more of the aggressive thinking which these students typify into our political life. "

Such sentiments would have been anathema just decade earlier. They would have given Smyllie a fit of apoplexy.

One of the most innovative elements in the old Sunday Review had been the "Backbencher" column, written by John Healy. It was surprising that Healy, who had taken little interest in politics, should have started the column following Gageby's encouragement, but in the event it was to prove one of the most controversial and influential political commentaries of the 1960s. Initially "Backbencher" caused a stir by printing information which clearly derived from leaks at Cabinet level (thought to have been Donagh O'Malley). It was political commentary with the gloves on, written by what appeared to be a journalistic bowsie, and the readers lapped it up. When the Review died "Backbencher" moved to the Irish Times, and though the Cabinet leaks gave way to a mixture of political gossip and ribald commentary the column played a major role in popularising politics, and in dispelling the air of respectfulness in which political journalism had up until then been cloaked. Each column was reputedly scrutinised by the paper's barrister, Samuel Crivon, but it sometimes appeared that individual "Backbencher" pieces were passed for publication not on the basis that they weren't libelous, but on the belief that the victim would not sue.

Unlike many of the journalists of his generation John Healy did not start out wanting to be anything other than a journalist. At the age of 18 he got a job with the Western People, pretending that he was proficient at shorthand. In 1959 he edited the Sunday Review and later the Evening Mail. His series of articles, "No one shouted stop", in the Irish Times, played a significant role in changing the official attitude to western development. An often boorish man, the sensitivity which enabled him to achieve a reputation as one of reland's most perceptive political and social commentators is kept hidden under a rural roughness, part genuine, part persona.

As well as having worked together for almost thirty years, Healy and Gageby are close friends who often chat on the phone for long periods. They once shared a cottage in Galway while both were writing books. To some associates Healy is "Gageby's blind spot", while others attribute to him Gageby's fascination with things rural and the Irish national traditions. Healy left the Irish Times in February 1976, having been lured by a reported £15,000 a year offer by the Independent. The NUJ objected to the move, at a time when the Independent was threatening to make several journalists redundant, and Healy collected his fee without ever having to write a wprd for the paper. A year later he put his money into a new provincial paper, the Western Journal, and was brought back to the Irish Times on a contract basis to write his "Sounding Off' column when Gageby resumed the editorship.

As well as having worked together for almost thirty years, Healy and Gageby are close friends who often chat on the phone for long periods. They once shared a cottage in Galway while both were writing books. To some associates Healy is "Gageby's blind spot", while others attribute to him Gageby's fascination with things rural and the Irish national traditions. Healy left the Irish Times in February 1976, having been lured by a reported £15,000 a year offer by the Independent. The NUJ objected to the move, at a time when the Independent was threatening to make several journalists redundant, and Healy collected his fee without ever having to write a wprd for the paper. A year later he put his money into a new provincial paper, the Western Journal, and was brought back to the Irish Times on a contract basis to write his "Sounding Off' column when Gageby resumed the editorship.

In his first seven years as editor Douglas Gageby added 22,000 to the average daily circulation of his paper. In the following four years the circulation would continue to rise until it was just short of 70,000, double its 1964 circula-

tion. The Independent was selling 170,000 copies per day and the Press was just over the 100,000 mark, yet the influence of the Irish Times was vastly greater. The other papers were only now adjusting to the changes in Irish society and the Irish Times had established a reputation for accuracy and comprehensiveness which made it more reliable. The Independent, on the other hand, had reacted by turning to sensationalism, even inventing sensational stories if none existed, its conservatism combining with titillation, like a nun kicking up her skirts. (One notable recent invention was the "exclusive interview" with Teddy Kennedy, by-lined to an Independent reporter who happened to be in New York. The story had been lifted from the Christian Science Monitor and the reporter had not seen Kennedy, much less interviewed him.)

In 1971 at the height of his triumph, Douglas Gageby delivered a speech to the Extra-Mural Adult Education Course at UCG in which he noted that "the class papers, as they are called, are particularly vulnerable. About 70 per cent of their revenue is from advertising and only about 30 per cent from sales. Thus a slight breeze in the economy, a slackening of consumer demand, can bring, even with a swing of 10 per cent, disaster".

A more than slight breeze was on its way, and the Irish Times, with its dependence on property advertising, was to be brought to the brink of financial catastrophe. In the process, much of the reputation which Gageby had built for the paper was to be eroded.

Exit Gageby, Enter Pyle

In the last week of June 1974 Fergus Pyle picked up a phone in Luxembourg to hear a voice from Dublin say that Douglas Gageby was about to retire and Pyle was being offered the editorship. Having left Belfast in 1970 to become Paris correspondent and later EEC correspondent in Brussels, Pyle had been away from the home office for seven years. He and his family were happy in Brussels and Gageby would be a tough act to follow, so Pyle was at first reluctant to accept. However, the temptation was too much and nine days later he walked into the Irish Times office as editor.

![]() The abrupt appointment caused uproar among the staff. One reporter who considered himself close to Gageby had been working alongside the editor until late the previous evening and had not received a hint that there would be a change of editor the following day. Why Pyle?, was the question. Although considered an excellent reporter he did not show any abilities which would make him an obvious choice. Why not Donal Foley? True, Gageby announced that he wanted to turn the paper over to a younger man. True, Foley's health wasn't the best. But, as Gageby's right-hand-man, Foley had been responsible for much of the success of the previous decade. It was his judge of character which had resulted in the hiring of the best of the journalists and his instinctive radicalism which had helped liven up the paper. A good-humoured and tolerant man, he had encouraged loyalty to the paper by abandoning such disciplines as suspension for lack of punctuality, which still prevailed in the Press and Independent.

The abrupt appointment caused uproar among the staff. One reporter who considered himself close to Gageby had been working alongside the editor until late the previous evening and had not received a hint that there would be a change of editor the following day. Why Pyle?, was the question. Although considered an excellent reporter he did not show any abilities which would make him an obvious choice. Why not Donal Foley? True, Gageby announced that he wanted to turn the paper over to a younger man. True, Foley's health wasn't the best. But, as Gageby's right-hand-man, Foley had been responsible for much of the success of the previous decade. It was his judge of character which had resulted in the hiring of the best of the journalists and his instinctive radicalism which had helped liven up the paper. A good-humoured and tolerant man, he had encouraged loyalty to the paper by abandoning such disciplines as suspension for lack of punctuality, which still prevailed in the Press and Independent.

What, in the liberal Irish Times, seemed an almost heretical suspicion, began to grow among the journalists, both Catholic and Protestant. Could it be that Foley was denied the job because he was a Catholic? Despite all the changes in the paper might the old sectarianism be alive at the heart of the paper which had presented itself as the champion of liberalism?

After the initial hostility and suspicion the journalists accepted the fact that Pyle was there to stay. Soon the old habits of respecting the authority of the editor asserted themselves and Pyle began to feel that he had the loyalty of the staff. Yet the manner of Gageby's departure and Pyle's appointment created a feeling of unease which was to linger through the disasters of the next three years. Gageby had moved up into a management position (another "pottering around" job, which he left a few months later) following a complicated deal setting up Irish Times Trust Ltd. The Trust, it was announced, had been set up to ensure that the paper would be "completely protected from outside takeover or control." The Board of the Trust seemed to have been appointed by a computer programmed for liberalism, composed as it was of carefully measured proportions of Catholics: Protestants, a Jew, Northerners, Southerners, trade unionists, businessmen and a woman. Three of the directors, George Hetherington and the two Walker brothers, left the Board of the paper while the fourth and fifth directors, Gageby and McDowell, remained. "Journalism benefits", according to an Irish Times editorial on the deal, "The newspaper-reading public benefits. All those who work in this newspaper will submit, humbly, that the people in general benefit."

Five people in particular benefited. The directors sold their shares to the Trust at a price of £1 ,625 ,000, averaging out at £325,000 each. The price was based on the 1972 profit of £242,134 and the expected profit of 1973 (around £400,000) and was, according to the Irish Times financial correspondent, "at the high end of an arguable price range". Ironically, in view of the financial disasters of the next few years, any profits from the paper were to be distributed by the Trust. In the event, the £1.6 million which the paper had to borrow from the Bank of Ireland in order to pay the directors was to become a financial milestone.

Five people in particular benefited. The directors sold their shares to the Trust at a price of £1 ,625 ,000, averaging out at £325,000 each. The price was based on the 1972 profit of £242,134 and the expected profit of 1973 (around £400,000) and was, according to the Irish Times financial correspondent, "at the high end of an arguable price range". Ironically, in view of the financial disasters of the next few years, any profits from the paper were to be distributed by the Trust. In the event, the £1.6 million which the paper had to borrow from the Bank of Ireland in order to pay the directors was to become a financial milestone.

McDowell insists that he, Gageby and the other directors could have received a substantililly higher price for their shares on the open market but they preferred to sell to a Trust as the paper "had never been a wholly commercial operation". Many of the journalists were resentful that Gageby in particular should walk off with a bulging wallet, and that resentment grew deeper as the paper's finances grew shakier. Pyle does not ascribe all his problems in the following years to the financial chaos, yet whatever chance he had of making a success of the editorship was already being undermined. A senior journalist on another paper, commenting on Pyle's appointment, said, "They took the pips out of the orange and left him the skin."

Gageby'S work habits had always been irregular. He would sometimes arrive at the paper at 9 am and work on into the small hours of the following morning. After a few days of this he would disappear for a couple of days fishing. The paper had been to a large extent shaped around this routine and for the first three months Pyle attempted to fill the gap left by Gageby's departure. Then his wife and four young children returned from Brussels and he reverted to a more normal working schedule, appointing Jim Downey and Dennis Kennedy assistant editors. Perhaps symbolically, Pyle moved out of the large room where Gageby had worked alongside senior staff members and into the privacy of the smaller adjoining room previously occupied by Gageby's secretary. The physical isolation would later be echoed by isolation of another kind.

Pyle's editorship coincided with two significant events. It began at the end of the National Coalition's "honeymoon period" and lasted until just after they were removed from office, bracketing a period in which civil rights and press rights in the Republic came under savage attack. It also coincided almost exactly with the duration of the economic recession begun in 1974. Gageby could not have foreseen this, so there was no question of him deliberately dodging a tough period. Yet it would have been interesting to see if he could have maintained his glowing reputation during that period.

The problems created by these outside events compounded the problems which Pyle was already encountering. Displaying a certain reserve, he did not have Gageby's ability to manipulate people, to persuade them to follow his instructions without appearing to dictate. Whereas Gageby's brief for a story would be delivered verbally and with a minimum of formality, Pyle would produce long memos giving precise details of the kind of story the reporter was to bring back. Similarly, while Gageby's news conferences had been snappy twenty-minute affairs Pyle's would meander interminably. While some journalists saw this as a genuine attempt to provoke discussion on issues others resented Pyle's lecturing style.

The long news conferences on occasion had an adverse affect on production of the paper, creating an impression that Pyle was insensitive to production requirements. If the printing of the Irish Times is delayed even hy minutes it can result in extra expenditure or lost sales. The paper must be ready by 1.30 am to be dispatched throughout the country by CIE lorries. If the other daily papers miss the lorries they can call in the vans which they use to distribute their evening publications. The Irish Times has few vans and is dependent on the CIE lorries. A missed deadline can mean that the paper is faced with losing readers in country areas or hiring vans to do a special distribution run.

Indecision on Pyle's part and frequently wrong decisions resulted in regular losses of such kind. For instance, on the night of June 17, 1977; when the General Election results were coming in. Pyle insisted that the results be laid out in a simplistic tabulated form, with neat rules dividing the results. Such a layout is extremely complicated and slow to produce but Pyle refused to revoke his decision. As a result the lorries were missed and many thousands of country readers lost.

Whereas Gageby has a good eye for an interesting photo and a lively layout Pyle preferred great slabs of print across the front page in the manner of certain continental papers. He also encouraged bland light sociological features and the combination resulted in a dull paper. Sales remained steady throughout 1974 and 1975 and began a steep dive at the beginning of 1976. At the same time, the quality of the reporting deteriorated. As well as inhibiting reporters by giving precise details on how a story should be written Pyle reacted to the repressive mood of the Coalition period by blunting further the paper's liberal teeth. Donal Foley has written of the I 960s: "The year 1963 was a great time to come back to Ireland as news editor of the Irish Times. It was a time for extending frontiers ... The role of the Irish Times in the circumstances was clear. It should be a forum for discussion, a mouthpiece for all minorities as well as the majority, and a paper with a clear-cut radical viewpoint. Guided by a radical editor this was the path we took."

While the radicalism of the Irish Times had always been within the liberal consensus of the emerging middle class, it had played its part in by-passing the old frontiers. By 1976 the new frontiers were pushing back. And Pyle took the paper back with them. He had left Belfast in 1970 morally exhausted and disillusioned after three years reporting the conflict, disappointed that his earlier optimism had been dashed. In Brussels he had formed relationships with Irish politicians on EEC business, fellow Irishmen abroad, and at home he enjoyed the diplomatic reception circuit, something Gageby has always avoided. He was a sucker for the "mindless thugs" explanation of the continuing conflict and the paper suffered accordingly. One reporter complained that the emphasis on "balance" was such that reports of a plane crash would soon have to be "balanced" with reports of all the planes that landed safely that day. When the Peace People phenomenon erupted in August I 976 Pyle supported it blindly, to the extent of arranging a drinking session in Hunter's lounge, near the Dail, between Peace leaders and some of his less than enthusiastic staff.

Following the killing of Garda Michael Reynolds the juryless Special Criminal Court tried and found guilty Marie and Noel Murray and sentenced them to death. Although hangings traditionally offend the liberal conscience the subsequent protests organised by the Murray Defence Committee, often involving hundreds of people, went virtually unreported in the Irish Times.

Pyle was not alone in succumbing to the oppressive conservatism of the time, and few of the Irish Times journalists are proud of their role in that period. Most of them had other things on their minds. Such as the prospect of losing their jobs.

In mid-1974, when Gageby left, the indications had been that there would be a £400,000 profit by the end of the year. Then came the "slight breeze" of which Gageby had warned and by the end of the year the company had suffered a £100,000 loss. The effects of the oil price rises and the international economic recession were beginning to filter into the Irish economy and firms whose budgets had gone haywire began to reduce the amount they were spending on advertising. The Irish Times, with a high dependence on property and "upmarket" advertising, was particularly badly affected.

The losses continued in 1975 and in late 1976 management was shaken by a revelation of their own incompetence. In negotiating with the unions, claiming inability to pay the National Wage Agreement, the management had released figures which they believed showed the company's losses. Three months later they had to admit that they had got the figures wrong by £210,000. This inability to even get their sums right cut the ground from under the Board's feet and lost them Credibility with both the unions and the bank, to which they were in debt to the tune of £2.5 million. There was a real fear among the journalists that the paper was about to fold and there was a consequent increase in conservatism. Rocking the boat is fun, but when the water starts splashing aboard there is a tendency to seek calm.

Following the rise in cover price to 15p in January 1976 circulation had begun falling by 500 copies a week. By the end of the year circulation was down below 62,000, the worst figures in six years. Pyle did not have the same power in the company as Gageby had, and didn't have the same close working relationship with Major McDowell, making it more difficult for him to get money to promote the paper. In a reversal of his tactics of the early 1960s, and with the encouragement of whizz-kid Peter O'Hara, who had been brought on to the Board, McDowell began looking for economies. The process of cutting back only increased the problems. Newsagents, for instance, were told they would have to cut down on the number of papers they were returning, and they consequently cut down on their orders. Lack of money affected the quality of the paper. There were restrictions on reporters travelling too far from the office. Often they would be told to phone an expert, usually a TCD sociologist, rather than go out to prime sources themselves.

Pyle on the Slide

The turning point for Fergus Pyle came in mid-1976. On June 11 a deputy chief sub-editor, Niall Fallon, rushing to meet a deadline, allowed a statement from the Association of Legal Justice to be patched on to a five-paragraph article by Dick Walsh, the political correspondent. The statement included the term "sentencing tribunal", as applied to the Special Criminal Court, which had sentenced the Murrays to death. This was in a period when the Irish Press had to fight (and win) a charge of scandalising the same Court by publishing a letter from solicitor Gerald Goldberg, alleging that his client had been beaten by Gardai. Hibernia was taken to court for putting quotation marks around the word "trial". Within a month Pyle found himself in the High Court to answer a charge of contempt.

Pyle's response infuriated his staff. Whereas the Press had fought the case Pyle circulated a memo restricting the terms under which press statements giving "political, social, legal or other views" could be printed. "Phrases like 'a spokesman said' should be avoided," he warned, restricting the discretion of the journalists in using material obtained from unnamed sources. In court he expressed his "respect for the Special Criminal Court and desire to maintain the prestige and dignity of the judges who compose that court". Worse still, in the course of questioning Pyle was asked if he had been in the office that night. Replying to what he believed was a simple matter of fact, he said that he was not. Because he had not made an explicit statement accepting responsibility for his publication whether he was physically present or not, as editors are traditionally obliged to do, Pyle gave the impression that he was passing the buck to Niall Fallon. This added to an existing belief that Pyle did not have the same trust in or loyalty to his staff as Gageby had. Gageby might bawl out a reporter in private but he would strongly and coldly reject outside criticism of his staff. The NUJ Chapel had to resist motions of no confidence in Pyle, arguing that the anger should be channelled into more practical avenues. From that point on Pyle's days as editor were numbered.

On Monday, February 14, 1977, the Irish Times front page headline ran, "Gardai using Northstyle brutality in interrogation techniques". The story introduced a series of articles by Don Buckley, Joy Joyce and Renagh Holohan which detailed the activities of the Coalition's Heavy Gang and which ran as front page leads for three days, prefacing extensive coverage of allegations of garda brutality on the paper's "Focus" page. The paper had grown so dull, stale and conservative that the Heavy Gang series came as a surprise, although such allegations had been common knowledge in journalistic circles for some time. On the night of publication the story had caused a buzz of excitement within the Irish Times itself. As the copy was processed through the setters and into the case room the printers began making excursions upstairs to the newsroom to ask, "Is there any more of this stuff?"

Later on, Pyle would refer to this story as one proof that the paper had not grown timid under his editorship. He believed that the story was one reason the Irish Times lost sales among Fine Gael readers (the other being the paper's disapproval of the appointment of Dick Burke as an EEC Commissioner. Pyle felt the Fine Gaelers interpreted the opposition as a reaction to Burke's conservative stand on contraception, while Pyle genuinely believed that Burke was not suited to the job). In fact, any negative reaction from Fine Gaelers would have been more than offset by a positive reaction from those who saw the Heavy Gang series as an indication that there was still life in the paper.

Although Pyle had known the investigation was under way he had no idea of the explosiveness of the story and the reporters were wary of handing over a sheaf of typed allegations too far ahead of publication for fear that publication would be affected by the prevailing atmosphere of caution. By Saturday, February 12, two days before publication, with the story being advertised for the following Monday, not a word had been written. On Sunday evening, Pyle's response on seeing the case histories of allegations, which had been written up over the weekend, was to demand that affidavits be procured from those making the allegations. "How do we know these people are telling the truth?" he demanded. By now the newsroom was buzzing with news of the story, the reporters were excited, the subs were aware they were handling something unusual, and even Donal Foley, who had come in that evening, was reading the copy hot off the typewriters, his eye carrying a glint that hadn't been seen in a long while.

Although Pyle had known the investigation was under way he had no idea of the explosiveness of the story and the reporters were wary of handing over a sheaf of typed allegations too far ahead of publication for fear that publication would be affected by the prevailing atmosphere of caution. By Saturday, February 12, two days before publication, with the story being advertised for the following Monday, not a word had been written. On Sunday evening, Pyle's response on seeing the case histories of allegations, which had been written up over the weekend, was to demand that affidavits be procured from those making the allegations. "How do we know these people are telling the truth?" he demanded. By now the newsroom was buzzing with news of the story, the reporters were excited, the subs were aware they were handling something unusual, and even Donal Foley, who had come in that evening, was reading the copy hot off the typewriters, his eye carrying a glint that hadn't been seen in a long while.

Some of the staff wanted to defy Pyle's demand for affidavits, others wanted to agree and then do nothing about getting them. They argued with Pyle, telling him that if he wanted lawyers to write the paper he should employ lawyers, that the reporters trusted their sources. When the front page lead was handed to Pyle at about 9.30 that evening he seemed already to have abdicated and did little more than glance at it before wandering out of the office. The atmosphere was such that had he tried to stop publication at that stage his orders might have been disregarded or there might have been a walkout of the staff. The paper had been hijacked from under him.

The next day, as the ripples from the story spread and other sections of the media ran to catch up, with reporters from the BBC seeking out Times staff for comment and background, Pyle seemed to brighten and take some hesitant pride in the fact that his paper had made a stand. It is probable that the series helped put the brakes on Garda brutality in that period. It was also a milestone on the road to the removal of Pyle from the editorial chair less than five months later.

Pyle had joined the paper under Alec Newman's editorship and one afternoon, in the third week of Pyle's trial month, Newman stopped on his way to a news conference and gave a broad hint that he was happy with Pyle's work and would be keeping him on. The news conference lasted longer than usual and when Newman emerged he walked over to Pyle and murmured, "The bastards have pushed me out." Pyle's own exit, sixteen years later, was to be as abrupt. Palace revolutions can be cruel.

Gageby had kept in touch with the paper and was aware of the problems. He talked with Major McDowell and with Pyle and had passed on a message, through Pyle, asking the journalists to a meeting "to chew the fat". A group of NUJ representatives composed of Paul Gillespie, Don Buckley and Dick Walsh went to Gageby's house to discuss the situation. In meetings with McDowell and the NUJ it was suggested that Gageby come back and Gageby let it be known that he would be available. By this time management seemed as eager to ditch Pyle as were the journalists. At a "one last try" meeting between the journalists and Pyle, General Manager Louis O'Neill sat in silence as the staff waded into Pyle. When Pyle left the room to make a phone call O'Neill let the journalists know that he was in agreement with them. When Pyle returned O'Neill resumed silence.

Over the last few months Pyle grew more antagonistic to his staff, lecturing and hectoring and blaming them for the paper's troubles. In return, they did little more than clock in, with no commitment to the paper and without the enthusiasm to generate ideas. Privately, Pyle wanted to get out of the job but felt obliged not to resign or run away from the job. When it was put to him by the Board that he should stand down in order to allow Gageby to return he immediately agreed. Members of the staff who had had to conceal their high personal regard for Pyle while bitterly opposing his editorship now felt relieved.

There had been a suggestion that a triumvirate might be set up, with Pyle and Donal Foley reporting to Gageby. It was thought best, however, to leave the paper in the hands of the architect of the 1960s success. Even Pyle felt that there was a rightness about Gageby returning as the saviour of the paper.

Climbing Again

These days Gageby refers to his three years away from the paper as his "sabbatical". He wrote a book on growing up in Belfast and collaborated with Louis Marcus in the making of Heritage, an RTE series dealing with Irish history, and the reading and research which he had to carry out increased his interest in rural life. The Irish Times had always been an urban paper and even in the late 1960s over 80 per cent of its circulation was in urban areas, and almost 60 per cent in Dublin.

Just as Gageby seemed to have mellowed during his sabbatical so did the Irish Times on his return. On the day he returned joy was unconfined in the Irish Times building. At one point, according to one journalist, there was dancing between the desks in the newsroom. Assistant editor Jim Downey, trying to preserve his accustomed air of aloofness, caught the eye of one of the reporters and burst into laughter. Reporters were crossing the newsroom to excitedly pump Gageby's hand. After the ball was over it was back to business.

Since Gageby's return the paper's daily circulation has soared. In 1978 it passed 70,000 copies a day, more than were sold before his 1974 retirement. This year the paper passed the 75,000 barrier. The revival resulted from a combination of Gageby's talents and an easing of the economic recession leading to increased spending on advertising.

The paper improved visually. At one point Gageby remarked that the paper hadn't enough pictures of women. "Women are half the population, but we're always running pictures of men. " A couple of photographers promptly came back from Stephen's Green with shots of women lazing in the sun in various stages of undress. "If I wanted pictures of cunt, I'd have asked for pictures of cunt!" stormed Gageby. However, it wasn't long before Maeve Binchy was despatched to the beaches of Europe to write an interminable series of holiday articles, some of which could be credibly illustrated with photos of topless women bathers.

The paper's "Focus" page began to run one series after another, sometimes stretching a subject over several days when it could have been covered in a single article. Such series made the paper easier to promote, as special promotional material could be printed for a series which would run for several days. In the first year of Gageby's return £100,000 was spent on promotion, much of it on radio. Stickers, metal placards, posters and bus advertisements blossomed. Gageby could pull the financial strings which had been kept out of Pyle's reach, and Conor Brady, who edits the "Focus" page, is also charged with the job of promoting the paper.

Some of the series were geared towards rural areas in order to break out of the urban straitjacket. The Garda brutality story was dropped and although morale within the paper continued to climb there was no more adventurousness than there had been in Pyle's time. Gageby seemed as exhausted with and tired of the Northern issue as Pyle had been. Writing of the first issue of the Evening Press, on its twenty-fifth anniversary, he noted, "The lead story that day, believe it or not, was that the RUC had banned a march in Newry. And guess what the lead story will be on the morning of the 50th anniversary?" Journalists in the Irish Times are themselves aware of the paper's flabbiness but point out that today the social controversies are not as black-and-white as they were in the 1960s. There is a genuine confusion about what the role of the paper should be in the 1980s.

Some of the series were geared towards rural areas in order to break out of the urban straitjacket. The Garda brutality story was dropped and although morale within the paper continued to climb there was no more adventurousness than there had been in Pyle's time. Gageby seemed as exhausted with and tired of the Northern issue as Pyle had been. Writing of the first issue of the Evening Press, on its twenty-fifth anniversary, he noted, "The lead story that day, believe it or not, was that the RUC had banned a march in Newry. And guess what the lead story will be on the morning of the 50th anniversary?" Journalists in the Irish Times are themselves aware of the paper's flabbiness but point out that today the social controversies are not as black-and-white as they were in the 1960s. There is a genuine confusion about what the role of the paper should be in the 1980s.

The Irish Times had not been extending any new frontiers in the wake of the social changes of the 1960s, merely trying to find them. The conservative backlash of the mid-1970s made clear enough where those frontiers were and since then the paper has been happily spreading its roots and boosting its circulation within them.

Back in his Press days Douglas Gageby left the Burgh Quay office one evening and dropped in to the Pearl Bar to have a drink before going home. He called aside by then the editor of the Irish Times, R. M. Smyllie, who demanded to know why Gageby wasn't working for the Times. Gageby replied that he didn't like the paper, didn't like its politics, and wouldn't want to work for a newspaper whose staff was divided into gentlemen and players. Smyllie harumphed, stormed out of the pub and wouldn't speak to Gageby for six months.

If the day of the gentlemen journalist is gone it's equally true that the day of the highly paid players is here. Unlike in Smyllie's day, journalists are not hired on a whim, paid low wages, tried out for a few weeks and allowed to wander off if they can't make it. Wages were so low that a few mistaken hirings were acceptable.

Unlike in the 1960s, journalists are not hired according to the instincts of a Donal Foley or a Gageby. Wages are so high and grading agreements so well-monitored by the NUJ that grace and favour has given way to careful selection by a panel. The old way had the drawback that people were sometimes hired for their writing ability alone and turned into stars, leading to problems later on. However, it would be hard to imagine a panel having the insight to hire some of the talents of the 1960s. Some of the innovations of the 1960s are beginning to show flaws. Specialist correspondents, in developing an expertise in a single subject have had to develop close relations with an even dependency on vested interests. As a result, sensitive areas may be ignored in order not to lose the confidence of those who feed information.

There was an element of truth in the old advertising slogan. If you missed the Irish Times quite often you did miss part of the day. The latest slogan, "Keep up with the changing Times", reflects the paper equally well. Some of the old columnists, notably Binchy and Foley, have been performing the same tricks for too long and John Healy's reporting and commentary degenerates on occasion into the pseudo-philosophical ramblings of a rural bootboy. Much of the content of the paper, the features in particular, seems to be chosen as much for ease of promotion as for its merit.

Gageby has taken the paper away from the brink of financial disaster but the debt to the Bank of Ireland will be a burden for many years yet. Meanwhile the old hot metal process is being phased out and the new computer typesetting is being brought in. The trick for the Irish Times will be to carry through this change, to maintain if not continue boosting circulation, to continue paying off the debts, to find a successor to Gageby, and to do it all in the face of the coming economic recession. Already the slight breeze of the credit squeeze has blown across the property advertising pages.

Gageby came back with the intent of staying for two years or so while the paper got out of its difficulties. The indications now are that he will stay another year or two, possibly three or four. Looking back to his retirement in 1974 he believes that if he had known that the recession was going to hit a few months after he left he might have stayed on. He is unlikely to leave again unless economic prospects are fairly stable. (the prospect of a Third Coming would be too daunting.)

There is a certain briskness to the steps of a number of senior journalists at the paper, all of whom are well aware that the succession stakes have begun. Negotiations following Pyle's abrupt and controversial appointment have ensured that the NUJ will be consulted and it appears that the union will have a virtual veto over the choice.

The front runner is Assistant Editor Jim Downey, who is well respected by the staff. However, a lengthy stay by Gageby may reduce the chances for Downey, who won't learn any more by waiting for several years. The reverse is true of Conor Brady, whose job in charge of promotion and of the "Focus" page puts him in a strong position. He is the dark horse in the race and his chances improve with every year Gageby stays. The possibility of Henry Kelly coming back to the paper as editor is the subject of much speculation, mostly by Henry Kelly. Conor O'Cleary was brought back from the London office so that a closer eye could be kept on his performance. The choice might be someone outside the paper and John Healy has been mentioned as a possibility. He however, is a stranger to the people and processes within the paper.

It is important that the decision be taken some time before Gageby leaves so that the speculation ends and the successor has time to ease into the job, unlike Pyle who went in at the deep end. In the meantime, there is talk of appointing a journalist to cover the USA on a fulltime basis and beefing up the Brussels office, so the disappointed contenders will have consolation prizes available. (Gageby is rumoured to have promised to "lean over backwards" to ensure that the next editor is a Catholic. The office joke, following his effusive and emotional writing on the papal visit, is that the first Catholic editor will be Gageby.) There is little possibility of the next editor being a woman. One thing at a time.

The transition to the new technology has been creating more problems. In theory the new process is faster, in practice it has brought deadlines back an hour. This means that the paper uses more fillers and stories set in advance, thus reducing the amount of space available for later news. Because both the old and new processes are being used there are problems in aligning the different types of printing plates to ensure that equal pressure is applied to all pages, otherwise one will be properly iriked while another carries only a faint impression. While introducing the new process is supposed to reduce typesetting staff, it has actually increased the number.

The changing Times should ensure that the paper is better prepared to meet the next recession than it was to meet the last. The Bank of Ireland was extraordinarly tolerant of the paper's financial problems in 1976 and supported the paper partly because of the Trust agreement but mostly because of McDowell's record of clearing up the financial mess in the eariy 1960s. The Irish Times cannot count on such tolerance continuing indefinitely and, even if it makes for a duller paper, the hatches are being battened down for the future.

The 5 pm news conference was almost over when someone mentioned an AFP report that South Africa's ruling National Party had lost a by-election. Bruce Williamson looked up eagerly. ''We must do a leader, on that! It's the first time they've lost a by-election in, oh, it must be eighteen years. We should put it on the front page."