Jack Lynch: My Life and Times

Exclusive: For the first time, An Taoiseach, Jack Lynch writes about his background, his sporting career, his entry into politics, his ministerial career, and his period in office as Taoiseach.

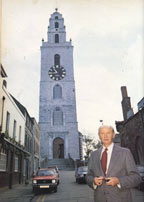

I was born at home near Shandon, in Cork, on August 15, 1917. I was the fifth son in the family, one of whom, died before I was born. There were two sisters both younger than me.

My father's family came from a small farm in the townland of Baurgorm, south of Bantry. The farm was later amalgamated with another and this, in turn, was again amalgamated. The fact that the holding is still a very small one gives some idea, of the size of the original holding.

In my father's family, there were three sons, my father, Dan, one brother, Jerry, who went to America and another, John, who stayed on the farm for a while and then followed my father to Cork. We lost touch almost completely with the American side of the family, although one of our Los Angeles cousins visited us over two years ago. I was out of the country at the time, but some of my brothers met him.

My father came to Cork city at the turn of the century and became an apprentice to a tailor, first at Daniels, a merchant tailor on Grand Parade, and later on at Cash's, one of the main drapery stores in Cork. When he first came to Cork, he shared digs for a while with J. J. Walsh, who became Minister for Posts and Telegraphs, in the first Free State Government.

He got married in 1908 to Nora O'Donoghue, whose family originally came from a farm near Glaunthaune, but they had moved into the city by the time my father came in contact with them. She was a seamstress and continued to work part time after they got married - a much needed supplement to my father's income.

Although we were not well off, we were always well dressed, even if our clothes were usually hand-me-downs. My mother's training as a seamstress made her fussy about our clothes and appearances. I suppose I learnt a certain fastidiousness, in that regard from her.

My mother was one of seven daughters in the O'Donoghue family, there were also two sons. One of her sisters married Bill Kelly, whose son Jim was, up to his recent death, of the Limerick Leader. Another sister, Statia, married Michael O'Reilly and they lived near us in Cork. They had three sons, two of them doctors in Dundalk and three daughters, all married in Cork.

My mother was one of seven daughters in the O'Donoghue family, there were also two sons. One of her sisters married Bill Kelly, whose son Jim was, up to his recent death, of the Limerick Leader. Another sister, Statia, married Michael O'Reilly and they lived near us in Cork. They had three sons, two of them doctors in Dundalk and three daughters, all married in Cork.

My father was a tall, dignified looking man, quiet and modest in all his doings. He liked a drink occasionally, and was interested in sports. In his day he played football, first in west Cork and then for a Cork City team, Nil Desperandum, now defunct, whose members were associated with the drapery trade in Cork. He was interested, in all sports, attending soccer and rugby matches as well as gaelic football and hurling. His main recreation, when I was young, was walking and occasionally throwing a bowl along the road, which, of course, is still a favourite pastime in west Cork and the environs of the city.

My memory of him is as a strict, but fair father. I was regarded as the wild boy of the family and, therefore, came into conflict with him more often than did my brothers, but we had a good father/son relationship.

He took particular interest in my sporting career and was often quietly critical of my performances, but always in a helpful way. I remember once after a match I had played for Glen Rovers, him commenting: 'You were rather lackadaisical today', which was quite true on the occasion and coming from him, a stern rebuke.

My mother was also a quiet person and naturally I was very close to her when growing up. I was absolutely shattered when she died unexpectedly when I was in my early teens. She had gone into hospital because of what we believed to be a minor ailment and we were expecting her home the day that she died. She had been fairly healthy up to then and had been in hospital for only a week or two. I remember my aunt, Mrs. O'Reilly, had gone into town to get some new clothes for my mother in anticipation of her coming out of hospital, when a nurse rushed up to the house from the North Infirmary IO, to tell us that she had died. I walked around the streets in a daze for hours before coming back home and for years later, I was deeply affected by the loss.

Our first home was near St. Anne's, Shandon. When my mother died, we went to live with her sister Statia's family, the O'Reillys, first to 5 Vernon View on South Douglas Road, but as this was three or four miles from the schools we were all attending, we moved back to the north side to 22 Redemption Road on the North side.

There were six of us, plus my father, in our family and, initially, two O'Reilly children, plus the two O'Reilly parents. However, ultimately there were six O'Reilly children, so the house was a crowded one, even though some of my older brothers had moved out before the younger O'Reilly children were born - 13 or 14 of us lived regularly in the house.

My three brothers all live in Cork. Theo, the eldest, is a retired national teacher; Charlie is a parish priest in Ballinlough and Finbar has recently retired from the Civil Service to take up a civilian job in Cobh. Rena, the eldest of the two sisters, is married to Gerard Dunne, principal of the Cork School of Commerce and Eva works in an insurance office, her husband, a doctor, having died some years ago. Both the sisters have large families.

Schooldays

My first school was St. Vincent's convent, in Peacock Lane. I was there for two years until 1925, when I went to the primary section in the North Mon, and was in "the Mon" for 11 years in all. One can't remain in a school for such a length of time without it having a profound effect and I suppose the North Mon has left its mark on me but how, it's difficult for me to say. It's a very competitive school, however, and maybe some of that rubbed off. They used to publish examination results in the papers and used to push scholarship classes very hard. They also concentrated strongly on sport and it was in this sphere I'm afraid, that I made most impact in school. My older brothers were all involved in sports, so it was natural for me at an early age, to play both hurling and football. At quite an early age, I remember feeling that I had an ability, especially as a hurler. This may sound rather cocky, but I think it was just a self confidence which is really an indispensable ingredient, in any successful sportsman, or maybe even politician!

Early on I played in local parish leagues and, of course, I started to play with North Mon in the Cork Colleges and Munster Colleges competitions - there were no All Ireland Colleges championships at the time except at interprovincial level on the lines of the Railway Cups.

I think it was recognised fairly early on that I had an ability as a hurler and frankly I took advantage of this for missing an occasional class, as I used to have allowances made for me by teachers who were convinced I was otherwise preoccupied, which may not have been always the case.

My older brothers - Theo, Charlie and Finbar – had joined Glen Rovers at an early age and I did likewise. There I came in contact with one of the great father figures of the Glen, Paddy O'Connell, who took a special interest in my progress, which suggested to me that he thought that I had some potential. He used to take me to some of the big Munster Championship matches and point out facets of play to me and the techniques of various players. For instance, I remember him getting me to watch Mickey Cross, the Limerick left half, back in the early thirties. He was one of Paddy's own favourites. I noted how he moved towards a ball, how he sized up to it, how occasionally he would let it pass him in order to create better space for himself, etc. I learnt quite a lot about tactics and I suppose about how to think about the game during these outings.

My older brothers - Theo, Charlie and Finbar – had joined Glen Rovers at an early age and I did likewise. There I came in contact with one of the great father figures of the Glen, Paddy O'Connell, who took a special interest in my progress, which suggested to me that he thought that I had some potential. He used to take me to some of the big Munster Championship matches and point out facets of play to me and the techniques of various players. For instance, I remember him getting me to watch Mickey Cross, the Limerick left half, back in the early thirties. He was one of Paddy's own favourites. I noted how he moved towards a ball, how he sized up to it, how occasionally he would let it pass him in order to create better space for himself, etc. I learnt quite a lot about tactics and I suppose about how to think about the game during these outings.

My best friend in North Mon was Michael Twomey whose father was a provisions merchant in Shandon Street. Michael did very well academically in DCC and got a job on the administration side of the College. He died of cancer in 1952. He was a very good student and we did our homework together. Other contemporaries at the time were Tadhg Carey, now president of UCC, Leo Skentelberry, who later became ambassador to Argentina and also Australia - he was involved in the accreditation dispute in Australia. Another school friend was Tadhg Carroll, now head of the Department of Labour.

Meanwhile my school career was making progress of sorts. I won a scholarship to get from Primary to Secondary school - I remember coming first in English in the scholarship exam, but not doing as well in other subjects.

I skipped the first year at secondary level in North Mon, and did the Inter Certificate there in my second year - we were expected to do the Inter twice, but in the event I didn't do it the second year because I was indisposed with severe congestion.

Inevitably, a number of my teachers at the time had a significant influence on me. There was Brother O'Byrne, who was the last teacher we had for Maths, Science and Geology – incidentally, chemistry was by far my worst subject. There was also Brother Malone who trained the hurling team. I had a particular attachment to Brother Lawlor, who later went to Argentina where he was killed in a motor accident. I remember well two lay teachers, John and Dan Moore. John taught Maths and Science and Dan taught Latin and English. Brother Moynihan, who later became Brother Provincial of the Southern Province, was one of our teachers and there was Brother McConville, who was in charge of the Tech., and was regarded by us as a mechanical genius - he used to make hurleys and was responsible for making the props for the school plays. Another lay teacher was Pat Callanan, who inculcated in us a great interest in Shakespeare. I had an easy time in fifth year because there were no exams and I was beginning to make a name for myself in hurling with the Glen. Indeed, I was chosen on the Cork team for a League match while still in my fifth year and was on the championship team the following year. I knew that if I was to go to University I would have to get a scholarship, as my father couldn't possibly have paid fees and maintenance. However, by then my interests were primarily with hurling.

My Leaving Cert. marks were not high enough to earn a scholarship. However, I also sat several other exams, all of which I got, and these gave me a choice of career. These exams were teacher training, the ACC, the ESB and the Civil Service.

Early Career

Immediately after I did my Leaving, I got a job in Dublin in a roundabout sort of way. My brother, Finbar, was in

the Department of Agriculture and just about this time the Dail, following a milk strike, had passed the Milk Supply Distribution Act, which set up the Dublin District Milk Board, under the guidance of Sean O Braonain, who later became Secretary of Roinn na Gaeltachta. He was then in the office of the Minister for Agriculture and had special responsibility in relation to the Milk Board. O Braonain was trying to staff the new Board and he enquired of Finbar if I would be interested in a job. O Braonain was a senior official with the Civil Service Hurling Club and he was anxious to recruit new talent to the club, as he was to the new Milk Board. Finbar contacted me and I accepted the job on a temporary basis, pending the results of the various examinations I had sat.

The headquarters of the Board were at 36 Upper Mount St. and I went into a flat with Finbar and a few friends at 46 Upper Mount St. That was in the autumn of 1936; little did I know then what significance that street would have for me later on.

When I received the results of the various examinations I had taken in June, I decided to join the Civil Service. I went home to Cork for Christmas 1936 and on December 29, I joined the Circuit Office in Cork, where vacancies had arisen unexpectedly. The County Registrar asked me to sit with him in court and after a while, he let me take over as acting registrar, sitting in the court on my own until 1943. In the six to seven years I worked in the Circuit Court, I gained a knowledge of law and legal procedures and naturally developed an interest in it.

It was possible at the time to do the Kings Inns Barristers' course on a part time basis at VCC for the first two years of the course and I started there in 1941 under the Professorships of D. P. O'Donovan, a well known member of the Cork Bar, and C. K. Murphy, a Cork solicitor. We also took lectures in sociology, economics and politics and one of our economics lecturers was Alfred O'Rahilly. David Marcus, now literary editor of the Irish Press, took the Bar course at VCC at the same time. In fact he was the only other Bar student with me at VCC then.

The final two years of the Bar course could be taken only at the Kings Inns, so it was obviously necessary for me to leave the Cork Circuit Court. My transfer to Dublin, within the Civil Service structure, was facilitated, again because of my sporting connections. Paddy 0 Ceallaigh, a principal officer in the Department of Finance and also chairman of the Civil Service Football Club, arranged my transfer to Dublin and I joined the Club - we won the Dublin Senior Football Club Championship in 1944, for the first time in the history of the Club.

In Dublin, I was attached to the District Court Clerk's Branch, which is near what is now the entrance to the new wing of Leinster House, close to where ministerial cars are parked when the Dail is sitting. I was able to get off work there during term time at 4.30 pm to attend lectures in the Kings Inns.

I wasn't in the District Court Clerk's Branch for long, however, as I was transferred to the Department of Justice proper to become private secretary to the Secretary, who was then, Stephen A. Roche - he was succeeded by

Tommy Coyne, who in turn was succeeded by Peter Berry.

Stephen Roche allowed me to continue the arrangement whereby I attended Kings Inns lectures and in 1945 I was called to the Bar.

Stephen Roche allowed me to continue the arrangement whereby I attended Kings Inns lectures and in 1945 I was called to the Bar.

I had to seriously consider what I was then to do, as I was making progress within the Civil Service and Bar practice is traditionally hazardous. However, on the toss of a coin I decided to practice law and I resigned from the Civil Service.

With some of my friends I went to Glengarriff on holidays in 1943 - the evening of a Munster final in which we had just played. There were a few girls in a group staying at the same hotel - the old golf links - and we teamed up with them going for hikes, swimming and in the evening at dances. Many a time we rolled back the carpet for an eight hand reel and then settled down to a sing-song. Two of the girls were Mairin O'Connor and her close friend, Beryl Fagan, now married to Brendan Smith of Dublin Theatre Festival fame.

Shortly after that holiday, I transferred to Dublin to continue with my bar studies, so I was able to keep up contact with Mairin, who was living there. We were married on August 10, 1946.

Entry Into Politics

My first political involvement occurred quite out of the blue. In 1946, the late William Dwyer resigned his seat for the Cork City constituency and the by-election was called for June 14. I had no previous involvement in politics. Remember I had been a civil servant from 1937 until I was called to the Bar in 1945, which was within a year of the by-election.

My father was not political and very seldom was politics even mentioned in our house. I remember when Dev came to Cork in 1932 during the general election campaign of that year going to the city boundary. I carried a banner for that rally and there was great feeling for Dev at the time. I was conscious of him being a marvellous, romantic figure.

I should also note that many of my West Cork relations, to whom I went on holidays frequently, were very anti-treaty and I suppose some of these instinctual feelings were transmitted to me.

Contrary to subsequent rumours, no approaches were ever made to me by Fine Gael, but I did get an indirect approach from Clann na Poblachta, for the 1948 election. A friend who was a butcher in Cork, Paddy Murphy, was friendly with a lot of the Clann na Poblachta people, asked me if I would be interested in standing. I immediately declined saying my interest lay with Fianna Fail.

Contrary to subsequent rumours, no approaches were ever made to me by Fine Gael, but I did get an indirect approach from Clann na Poblachta, for the 1948 election. A friend who was a butcher in Cork, Paddy Murphy, was friendly with a lot of the Clann na Poblachta people, asked me if I would be interested in standing. I immediately declined saying my interest lay with Fianna Fail.

The Fianna Fail approach prior to the 1946 by-election came from members of the Brothers Delaney Cumann in Blackpool. The brothers Delaney, who were from Dublin Hill, were killed during the Civil War. The Fianna Fail members who approached me were Maurice Forde, Pat McNamara, Bill Barry and Garrett McAuliffe. They called to our small flat in Summerhill.

However, a friend of mine, "Pa" McGrath, who had been a life-long member of Fianna Fail was seeking the nomination and I wasn't going to stand against him. I told the delegation from the Brothers Delaney Cumann, that I wouldn't seek a nomination on this occasion, but perhaps next time.

My first overt political involvement was at a meeting during that by-election campaign in Blackpool Bridge, where I made my first political speech. I confined myself solely to extolling the virtues of "Pa" McGrath. Michael O'Driscoll, barrister, stood for Fine Gael - I knew him well, as I worked with him. Tom Barry stood as an Independent and Michael O'Riordan, who was in the North Mon in my time, stood for the Communist Party.

McGrath won the by-election easily, getting elected on the second count, on Barry's transfers. The surprise of the by-election was the fact that Barry got fewer votes than O'Riordan - 2,574 to 3,184.

From 1946 to 1948, I had no active political involvement at all, but prior to the 1948 general election, members of the Brothers Delaney Cumann, approached me again and I was also approached by Tom Crofts, the Chairman of the Comhairle Geantar. This time I allowed my name to go forward.

I didn't go to the convention as there was a law dinner on the same night. During the dinner in the Metropole Hotel, I was informed that I had been selected and was asked to go to the court house to accept the nomination, which I did, clad in dinner jacket. I hadn't formally joined Fianna Fail at the time of being nominated.

Four candidates were selected, two of them outgoing. They were Walter Furlong, "Pa" McGrath, Sean McCarthy and myself. That night, I became a member of the Brothers Delaney Cumann and have been a member ever since.

The main issue of the 1948 election, was the cost of living. Having been in an area where there was a lot of unemployment, I felt that, at last, there was a chance that with Fianna Fail policies, something could be done, especially for the north side and the Blackpool areas.

Having played with Glen Rovers, I was identified very much with the Blackpool area, where there was a strong nationalist tradition dating back to William O'Brien.

Glen Rovers decided they would conduct a campaign for me. The Fianna Fail organisation was not happy when the Glen put out special polling cards and did a personalised canvass for me. I asked Glen Rovers not to do it, but they argued that it was purely a private matter for them and didn't involve the Fianna Fail party. 1 went so far as to impound the personal canvass cards, but they got another supply.

There was some tension for a while as the other Fianna Fail candidates, quite rightly, didn't approve of what was happening. The tension died down however, when Tom Crofts, the director of elections, personally intervened and suggested that when canvassing, the Glen Rovers members should ask for support for the other Fianna Fail candidates and this they agreed to do.

I topped the Fianna Fail poll in the election with 5,594 first preference votes and Dr. Tom O'Higgins, 79, topped the overall poll with 7,351 votes. However, I was not to top the Fianna Fail poll again until the 1957 election.

"Pa" McGrath was a very popular man - an old IRA man with a prodigious memory which served him well in politics. He was Lord Mayor on a few occasions and few men ever worked harder for those he represented. We worked well together in the Dail.

I met Dev personally for the first time during the 1948 election campaign when he came to Cork for the final rally. He used to stay with Mrs. Dowdall, wife of the late Senator J. C. Dowdall whose brother T. P. Dowdall was a TO in the 30s. (Dowdall and O'Mahony were margarine manufacturers in Cork). In fact Mrs. Dowdall herself was a Senator and was appointed to the Council of Arts by de Valera. They had a big home in Blackrock. I met Dev in the house a couple of hours before the meeting. He was usually keen to find out at such meetings, what the local issues were. He then went back outside the town to make a processional entry. I had a reverential awe for him, but at that meeting I found him very human.

I was no stranger to Dail Eireann. I had been in the Dail before, for I had sought out Finian Lynch, a Fine Gael TO for south Kerry, for Stephen Roche, when Lynch was being appointed a Circuit Judge, this was around 1943/44, incidentally when Fianna Fail were in power.

I also had a lot to do with Donnacha O Briain, who was Fianna Fail Chief Whip. He used to speak much in Irish to me and I responded not very well, although I did go to Ballingeary and Ballyferriter in my younger days. It was only after I became a TO, that my speaking knowledge of Irish improved. In North Mon in the last two years, I did all subjects through Irish. I felt that, as one of the new generation who had learned Irish at school, I should use Irish-in debates and I did from time to time. It began to come easy to me after that.

Fianna Fail went into Opposition after the 1948 election, having been in power for 16 years. Naturally, the party took a while to acclimatise itself to these new circumstances. One of its first decisions was to appoint a researcher and secretary to the Parliamentary Party. I was asked to take on both jobs, having been promised that I would still have time for my Bar practice. I agreed, but quickly found that these duties involved me full time, especially as I was expected to help draft speeches for Dev, index Dail debates and newspaper reports, prepare briefs for front bench members, etc.

I stayed with the job for a year, but after that I went to Dev and told him that I couldn't afford to continue to neglect my legal duties completely. He understood my position and he took in Padraigh O Hannrachain as his own private secretary and this relieved me of most of the work I had been doing.

Parliamentary Secretary

After the 1951 election, I got the first hint that I was to be promoted to Government office when I went to my pigeon hole in Leinster House, to collect my mail on the day the Dail resumed. The Fine Gael TO for North Kerry, also Jack Lynch, father of Ger Lynch, who was TD until the last election, handed me a letter which he had mistakenly opened. He said something to the effect that the news would please me. It was a letter from Dev informing me of my appointment and asking me to come to see him.

I did so and he informed me in Irish, that he was appointing me to a new position, Parliamentary Secretary to the Government, with roving responsibilities for the Gaeltacht and the congested districts. Incidentally that was my first time in the Taoiseach's office - the same office that I occupy today - there have been very few alterations, one of them being that I have had the desk shifted from one side of the room, to another. The most major, is a complete change of decor, not surprising after so many years.

I reported directly to Dev in this position and I had offices for a while off the corridor known as the Burma Rd., in Leinster House. These were cramped and completely inadequate and so when Sean Lemass informed me that Liam Cosgrave's old offices in the Department of Industry and Commerce were vacant - Liam had been Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Industry and Commerce in the 1948-51 Coalition and Lemass had none - I readily moved.

One of my primary functions in this new assignment, was to head an inter-departmental committee representing nearly all the major departments (finance, agriculture, local Government, etc.), dealing with conditions in the Gaeltacht and the congested districts. One of the things we did, for instance, was to initiate a special scheme for Gaeltacht roads - Kruger Kavanagh used to refer to the road around Slea Head as "Jack Lynch's road". I had a head of Department and three executive officers, as well as a small typing staff.

The Cork Bar

When Fianna Fail were defeated in the 1954 election, 1 returned to my practice in Cork. I found it difficult to settle back during the first year, but by 1955, I had picked up the traces pretty well and the following year, my practice was flourishing. 1 got very few briefs through political connections, the late Martin Harvey, solicitor, a strong Fianna Faller in Cork, briefed me fairly regularly. My most regular briefs came from Michael (Collins) Powell who, as his name would suggest, had no connections with the Fianna Fail party.

Notables at the Cork Bar at the time included: Michael O'Driscoll, who was the leader of the Bar, Frank McCarthy Morrough, Frank Buckley, James Francis Meagher and the "Pope" O'Mahony. Sean Fawsitt, now a judge, was leader of the young generation of barristers. Denis P. O'Donovan, brother of John O'Donovan (former Labour TD) was there, John Gleeson, and William R. Ellis, recently appointed a judge of the High Court, Jim Desmond, and Bertie Willwood, both circuit court judges.

In the last year, I was earning as much money as I subsequently got as a minister. I had to forego £800 in brief, the very week I became a member of the Government in 1957 and that was a lot of money at the time. It was a special week of course, one of two weeks that the High Court sat in Cork.

I knew Dev was thinking of making me a Minister, but I wasn't very keen because I was doing fairly well at the Bar. Also, I found it very difficult in 1954, to catch up on recently decided cases and I felt I shouldn't again absent myself for so long, from Bar practice.

Ministerial Career

On St. Patrick's Day, 1957, I was working in my office in Cork and I got a phone call to ring Dev, who asked me to come and talk to him next time I was in Dublin. I went to see him as arranged and he offered me Gaeltacht or Education. We had two meetings after that before he finally offered me the Education portfolio. Dev asked me to hold the Gaeltacht portfolio as well and I did so for a few months before Michael 0 Morain was appointed to the Cabinet, as Minister for the Gaeltacht.

Prior to my acceptance of the position as Minister for Education, I told Dev that I liked the Bar and was beginning to feel that I had a good career there. However, as I hadn't got a family, I felt I wasn't risking too much, by going back into politics full time. My wife would very much have preferred me to stay at the Bar, but I felt I had an obligation to accept the offer, once it was made. I was, of course, flattered to be offered a Ministry at all.

I got on very well with Dev and liked him a lot. One of his traits I noticed particularly, was his meticulous attention to the words he used in public speeches. I used to help him on his speeches from 1948 to '49 and I learned a lot of the need for precision in speech, from Dev.

I was Minister for Education for only two years, but during that time, I was responsible for removing the marriage ban on women teachers. I also decided on a major building project at the training college in Drumcondra, following a visit there and talks with the then President, Fr. Cregan.

I restored the 6 per cent and 10 per cent cuts effected by the previous Coalition in vocational and secondary per capita grants and I doubled the rate of primary school buildings and also introduced the idea of an oral test in Irish for the Leaving Cert. This was to highlight the importance of speaking the language and we made this attractive by giving bonus marks for it. I tried to establish that as much attention as possible, be given to the spoken language.

I restored the 6 per cent and 10 per cent cuts effected by the previous Coalition in vocational and secondary per capita grants and I doubled the rate of primary school buildings and also introduced the idea of an oral test in Irish for the Leaving Cert. This was to highlight the importance of speaking the language and we made this attractive by giving bonus marks for it. I tried to establish that as much attention as possible, be given to the spoken language.

I established a commission to review accommodation and grants and as a result, there was a considerable increase in university grants, I asked that the committee should investigate whether Earlsfort Terrace should be expanded, but it was felt that the acquisition of new property in that area, would be very expensive, therefore, they would have to build upwards. It was then that the massive Belfield project got under way.

It was not absolutely a new experience for me to go into cabinet, for I had attended a few cabinet meetings from time to time, in the 1951 to 1954 period. Dev ran the cabinet more the way I do. I like to engage everyone around the table, like Dev did. I don't count heads. Nowadays, we argue it out and eventually I interpret a decision, if it has not already become clear cut. I usually have an idea myself in advance what decision I think is the right one and this is usually the one that we make, though not always.

Lemass was more direct in handling Government meetings. Under Dev, Government meetings went on very long and invariably, there were two meetings a week. It was fairly unusual to have two meetings a week, under Lemass. I'm somewhere in between.

When I was in education, I had very little difficulty in getting things through Cabinet. Dev, who had been Minister for Education at one time for a few months, was sympathetic to any demands I made. He used to ring up every now and again to enquire how things were going.

In Cabinet, Sean McEntee, precise on every subject, especially his own, was very forceful then, so too was Paddy Smith, in an earthy way. He brought subjects down to bedrock pretty quickly and he didn't confine himself to agriculture. Frank Aiken too was very strong. Sean Moylan used to scribble very good verse about some of the topics we discussed on Government meetings. What a pity somebody did not keep them.

Jim Ryan brought the first programme for economic expansion to the cabinet. We very quickly appreciated its worth and of course, Lemass supported it vigorously. It took really only one meeting to approve of the publication of Ken Whittaker's Economic Development, largely because it conformed to the thinking of most members of the Cabinet, especially Sean Lemass. Jim Ryan introduced it in a very bland way, which I suppose is ironic in view of its later significance, but absolutely typical of Ryan.

Though it was my first administrative job, I didn't find it difficult to cope. I had been in the civil service myself and had a good idea how the civil service worked. I never read only the top document on a file, usually a summary of what was written elsewhere, I always flipped over to read the conflicting arguments for and against a proposal. I also usually approached relatively junior civil servants in connection with an issue, when they were the people directly involved and when their memos impressed me.

I wasn't involved in Dev going to the Park and there was really no question but that Lemass would succeed him. I never detected any animosity against Lemass in Cabinet.

Dev announced his retirement at a party meeting and there was great emotion in his voice. He said that if elected, he would have to place himself above politics.

I was never among those who doubted that Fianna Fail would fare any less well under Lemass, than it had under Dev. I had enormous respect for Lemass, especially his direct approach and capacity to make quick decisions. I had an example of this in one of his first actions, on being appointed Taoiseach.

I was in my offices in the Department of Education, in Marlborough St., when I got a call from Lemass asking

me to come and see him in his Kildare St. offices - he hadn't yet moved into the Taoiseach's offices. It transpired he wanted to move me from Education to Industry and Commerce and I was none too keen on the change. In the first place, I felt I had a better command of the issues related to Education, than I had with the multifarious issues connected with the Department of Industry and Commerce, which incidentally included at the time, responsibility for transport and power. Secondly, I felt I was just on the verge of achieving something in Education and didn't want to leave just at that point.

His first words when I entered his office were, "I want you to sit at this desk". He prevailed on me to agree to the change (I suppose I had little choice), and I transferred over to Industry and Commerce, where I was to stay for six years. During that time, enormous changes occurred in our industrial life. In the first place, the high walls of protection gave way to freer trade, the Control of Manufacturers Act was repealed and foreign industry assiduously courted into Ireland. It was during this time, of course, that we first applied for EEC membership and incidentally, our application reached Brussels, before the British one did. However, de Gaulle vetoed the British application and ours lapsed as a consequence. .

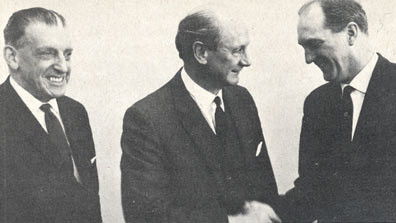

In the light of the failure to gain membership of the Common Market, we were keen to change the nature of our relationship with the British, to take account of our move towards free trade and to alter the unfair trading relationship between us and Britain, on agricultural produce. Lemass and I visited the then British Prime Minister, Harold MacMillan, in London, but there was no political will in Britain at the time, to engage in a venture such as this. It wasn't until the Labour Party came to power in 1964 that we were able to open negotiations, on what was to become the Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement, which was signed in 1965.

Industry and Commerce at the time was also responsible for all labour matters and I was being constantly called into the settlement of strikes, which provoked a mini cabinet crisis in 1964. This was when Paddy Smith, for whom I had great personal affection, resigned as Minister for Agriculture, in protest against what he saw, as capitulation to the trade unions. Although I disagreed with his views at the time, he was representing a growing tension between the industrial and agriculture sectors, as the industrial one, boomed under the expansionary Fianna Fail policies at the time and the agricultural sector lagged behind.

It took me some time to settle in at Industry and Commerce, but I felt in command of the job after a while and got considerable satisfaction from it, even though it virtually shattered my private life. Constant demands were being made on ministerial time, at public functions and engagements throughout and outside the country. There were a number of occasions during which I was called back from holiday because of strikes and my wife and I lost a few holiday deposits during that period. Sometimes when we were able to get away, for example, holiday weekends, it was at short notice and we often failed to get a booking. It was during this period, that we decided we would get a small holiday home some time, somewhere. We eventually bought it in 1971, in a beautiful location overlooking Carberry's hundred isles.

In all, I was six years in the Department of Industry and Commerce, during a time of rapid industrial expansion in Ireland. It was then that we made major changes on the structure of our industrial sector, from being protected, to becoming open to free trade - a development which was necessary to smooth our way towards EEC membership, which had been a goal of the Government's since the early sixties, but which was frustrated by de Gaulle's veto, of Britain's application to join. At the time, it was never really feasible for us to go in on our own, although since then, the degree of economic independence we have achieved from Britain, has become substantial, as evidenced by our joining the European Monetary System (EMS), while Britain has remained outside.

Department of Finance

As I've said previously, Lemass was still in his old office in Industry and Commerce. When he invited me to "take this chair" - the one he was sitting on. It was a formidable challenge precisely because he had been my predecessor, but it was all the more gratifying therefore, to realise that he considered I had done well - this was implicit in his offer to me of the position of Minister of Finance, after the 1965 general election. Many of the older element in the Government retired in that election, or about that time. As I've mentioned, Paddy Smith left the Government in 1964 and after the '65 election, Sean McEntee had gone to the backbenches, and Jim Ryan had gone to the Senate. It was a very considerable loss for the Government to have three such central ministers go almost together, but it allowed the younger element in the party to be promoted and this Lemass very much and very clearly wanted to accomplish.

It is little appreciated with what ease and tranquility Sean Lemass effected the transfer of power, from his generation, to another. In all countries, there are painful transition processes when such developments occur, but Lemass achieved this here with fairly considerable ease, although it might be said that his successor as Taoiseach, was the one to bear the full brunt of these difficult adjustments.

It is little appreciated with what ease and tranquility Sean Lemass effected the transfer of power, from his generation, to another. In all countries, there are painful transition processes when such developments occur, but Lemass achieved this here with fairly considerable ease, although it might be said that his successor as Taoiseach, was the one to bear the full brunt of these difficult adjustments.

Uncharacteristically perhaps, I was unphased by the challenge of taking over the central department of Government. However, from the outset, I was reassured by the presence as Secretary of the Department, of Ken Whittaker, with whom I had a very good relationship.

Naturally, the promotion to Finance fuelled speculation that I would be the successor to Sean Lemass, as leader of Fianna Fail and as Taoiseach. Quite early on, as the speculation mounted, my wife and I discussed the prospect and we concluded definitively that I should make it clear from the outset, that I would not be a contender for the position.

We had found that our family life had already been greatly disturbed by the demands of public office and we were both anxious to minimise this as much as possible. We both enjoy our own company in the privacy of our home, listening to music, watching television, reading or just chatting. Ministerial life didn't leave much time for private life and we knew that being Taoiseach, would leave even less time.

Quite apart from these considerations, I also found it difficult to visualise myself assuming the mantle of the likes of Eamon de Valera and Sean Lemass. They were both towering figures in my mind and the thought that I could adequately fill their place seemed to me, the height of presumption.

Nevertheless, the speculation about my candidature continued, even though whenever it was mentioned to me casually in the Dail restaurant, or in the party rooms, I dismissed it out of hand. Some of the older TDs were the most persistent that I should allow my name to go forward. These were Jimmy Collins, father of Gerry Collins, Tom McEllistrim, father of the current north Kerry TD, Martin Corry, Eugene Gilbride and Paddy Lenihan, father of Brian Lenihan - this list co-incidentally emphasises, the strong dynastic element, in Irish politics.

The Leadership

About 8 weeks before he eventually retired, this would have been about mid-September, 1966, Sean Lemass called me into his office and enquired if I was interested in succeeding him as Taoiseach. I told him emphatically that I was not and he seemed to accept it.

Some weeks later however, he called me into his office again, this time in the company of Charlie Haughey and George Colley and again he told us that we should be thinking about the future leadership of the party. I reminded him of my previous interview with him, when I said that I was not interested. I cannot precisely recall the response from the other two, but they seemed to indicate that they were interested.

It was following this latter meeting that "the succession stakes", as the press called it, really hotted up. Press speculation was rife, there was constant discussion about it in the party rooms, but I steadfastly remained apart from it all and repeated my disinterest on several occasions, when approached.

Apparently a group of old backbenchers went to Lemass, at the stage when Neil Blaney became a candidate. They were worried that the party would be damaged by division and dissension. They strongly pressed the case for getting me to stand as the sole contender, saying that I had clear majority support within the party over and above the other candidates anyway, that as I had remained aloof from the fray, I was not a divisive force within the party and that my varied and relatively long ministerial career, had suggested that I would be suitable.

Lemass' final decision to retire came rather suddenly. He dispatched a telegram to America, where George Colley was on an industrial promotional tour and advised him to come home. It was at this stage I believe, that the group of backbenchers went to Lemass and pushed for my candidature.

Lemass again invited me to his room, informed me that several backbenchers wanted me to run and that the party generally favoured me as his successor. He pointed out to me that I owed the party a duty to serve, even as leader. He gave me to understand, that the other contenders, to whom he had already spoken, were prepared to withdraw in my favour. I told him I would reconsider my position and would discuss it with my wife. We decided after a long and agonising discussion, that I would let my name go before the party. .

There obviously had been some confusion in Lemass' conversation with George Colley, for the latter, having considered his position, decided to stand as well. I rather welcomed the opposition, for it gave the party an opportunity to express its support and in the event, the count was 52 votes to 19.

Taoiseach

There was inevitably no radical change in the composition of the Government once I took over. As I've pointed out. Sean Lemass had already effected the transition from one generation to another and I had merely to endorse the changes he had made.

While superficially this made life easier for me, it did cause problems, for I was thereby deprived of one major strength every Prime Minister usually enjoys: the power of cabinet appointment. Of course, I had that power formally, but in effect, most ministers knew that they owed their position to Sean Lemass, not to me.

There was another difficulty, during the latter years of the Sean Lemass reign, he had deliberately allowed individual ministers a degree of personal freedom, which is unusual within a Government. He had frequently spoken of Government Departments as, "development corporations", which in itself implied a degree of independent initiative. He had also wanted to create the opportunities for ministers to show their individual flair and enterprise, prior to the change of leadership which he, almost alone, knew was in the offing, before it was generally suspected.

It was therefore incumbent on me to create a team spirit among the Government ministers, to impose a greater cohesion on the operation of the Government as a whole and to exert my personal authority.

This latter was made more difficult by being of the same age approximately, as most of my cabinet colleagues and thus, I was never viewed as a father figure within the party, as previous leaders had been. There was also the difficulty that I had become Taoiseach, not following a general election, but because of an internal party election.

One of the irritations I encountered at the time was that people, knowing of my reluctance to stand for the leadership, assumed that my first wish would be to get out of the job. They used to say things like, "don't worry you won't need to be there long - there is always the Park". The fact was that, from the moment that I became Taoiseach, I was determined to serve my stint there and not to run off at the first opportunity. I had no intention of being merely a caretaker Taoiseach. Neither had I interest in the Park then, nor will I ever have.

There was continuing trouble with the farming community in the period immediately after I became Taoiseach and again, this was due fundamentally to the fact that outside the EEC, agriculture had little scope for development and the main area of progress, was in the industrial sector. The population movement from the land to the towns inevitably caused considerable social tensions, which of course, had their political repercussions.

I was particularly fortunate that the first electoral test I had as Taoiseach, came in two by-elections, in Waterford and South Kerry. There could not have been two constituencies, outside my native Cork, that could have been more favourably disposed towards me personally - because of my sporting contacts, I knew many people in both areas and we won both elections, contrary to prevailing predictions.

The first electoral set-back I encountered, was in the PR referendum of 1968. It has been suggested that I wasn't to blame, as others in the party had pushed the proposal through the Government, but the fact of the matter was, that I was as keen on the change, as anyone else.

I had been very impressed by de Valera's reasons for proposing the change, in 1959. Several European countries had experienced protracted periods of political instability, with disastrous economic consequences, precisely because of the proportional representational system and with the experience of the two coalition Governments here, there were fears that this might happen in Ireland too.

In the event, we were beaten handsomely, but I did not interpret this defeat as an indication that the electorate had lost confidence in the Government and that we should go to the country. As I said in the Dail on November 5, 1968, "the rejection of the referendum proposals was no more a demand that the Government's period of office should be shortened, than that an acceptance of them, would be that it should be lengthened".

The EEC

The basis of Fianna Fail policy from the beginning of the sixties, was progress towards membership of

the European Economic Community, along with the United Kingdom. As I've mentioned already, a great deal of my work in Industry and Commerce, was devoted to restructuring Irish industry, for this eventuality. Almost immediately after I became Taoiseach, the prospect of joining opened up again, with the reactivation of the British application. I toured the EEC capitals to drum up support for our membership and generally was received cordially and got favourable indications of support for the Irish application, which had remained on the table since 1961. However, de Gaulle again vetoed the British application in 1968 and it was two years later before any progress was made in this issue.

EEC membership has already had enormous economic benefits for this country and has proved a great boost, particularly for our agricultural sector. True, the social and regional aspects of the community have been slow to develop, but the great effect membership has had on us, has been to remove Ireland's almost complete dependence on the British economy and to abolish the exploitive element, that was inherent in that dependence, primarily through the operation of the British cheap food policy.

Thus I regard the successful conclusion of negotiations for Irish membership of the EEC, as a major achievement and I was pleased to have been Taoiseach, when this historic event occurred.

The North

Of course, the North was to be, perhaps, my major preoccupation as Taoiseach. Very shortly after I took office, I travelled to Stormont to see the Northern Premier, Capt. Terence O'Neill - this was the time when my car was snowballed, by a handful of Ian Paisley's supporters.

I had enthusiastically supported Sean Lemass' initiative in seeing Capt. O'Neill a few years before, for it introduced an element of rationality to what was essentially, an absurd situation. From my childhood I had come to regard the division of our country as a blight on the land. That division was mirrored in splits and dissensions within almost every other national organisation - we had two trade union movements for a while, there were two athletic boards, two soccer authorities, two Chambers of Commerce in Cork, etc. I'm not of course suggesting that these various divisions were for the same, or similar reasons, rather that division seemed to be endemic to almost everything Irish.

I was never brought up to feel any antagonism to the Northern unionists, nor did I feel that their legitimate rights and aspirations should, or indeed could, be ignored.

I had little personal contact with the North, however, although Eamon de Valera did send me to a meeting in Coalisland in 1948 or '49, for a debate on unity. In spite of this, however, I always wanted to advance the cause of Irish unity by agreement and indeed, I referred again and again to this concept of unity by agreement, even before any of the troubles broke out in the North, in the autumn of 1968.

It had been suggested that unity by agreement was not always Fianna Fail policy, but rather, unity by peaceful means. However, I have always failed to see how unity by peaceful means, could mean anything other than unity by agreement and I think it was helpful to be explicit about this.

Although I had not travelled to Stormont for Sean Lemass' first meeting with Capt. O'Neill, I did attend the follow-up meeting at Iveagh House and afterwards had a meeting with Brian Faulkner, who was then Minister for Commerce in Northern Ireland. That meeting came about following an interview I did with Billy Flackes, the BBC Northern Ireland correspondent. I had announced as Minister for Industry and Commerce, that I would be prepared to give a 10 per cent preference to genuine Northern Ireland manufacturing firms exporting here, over and above what was provided for, in the Anglo-Irish Free Trade Area Agreement. Billy Flackes asked me if I would be prepared to meet Brian Faulkner to discuss the details of this scheme. I said I would and a meeting took place shortly afterwards. I found Faulkner to be very crisp and energetic. Nothing of a political nature related to the border, was discussed at this meeting.

It was obviously our hope that under the O'Neill conciliatory policy, the old attitudes in the North would soften and that gradually the Northern unionists would recognise that their future lay in a united Ireland, or at least, that the discriminatory practices towards the Catholic minority would cease and that there could be an end of animosity and bitterness on the island.

This was not to be. The civil rights movement in the North, which demanded ordinary democratic civil rights for Catholics, evoked hard line unionist opposition, leading to violence first of all from the loyalist side and then, when the situation was in turmoil, from the IRA, which leapt in to exploit the situation for its own ends.

I was unhappy from the outset about the introduction of British troops onto the streets of Northern Ireland, but their presence there soon became a political reality and there were obvious dangers in their precipitous withdrawal.

I expressed my initial unhappiness in my speech on August 13, 1969 on RTE, immediately before the introduction of the troops. While I think that my fears about their involvement in the six county area have been borne out by events, I acknowledge that once they were there and, more particularly, once they became part of the political geography of Northern Ireland, a pre-emptory withdrawal of the troops would have caused even further chaos.

The Northern situation gave a new dimension to the position of Taoiseach because for the first time, at least in our generation, the words one spoke, could have resulted in the loss of lives of fellow countrymen in the North. It imposed a great strain on the office and made one circumspect about all one said and did, while at the same time there remained an obligation to spell out the basic political realities of the situation, without the resolution of which, there could be no permanent peace.

I was careful to pursue a consistent political line throughout, on my handling of the Northern situation. At the Fianna Fail Ard Fheis in January 1969, I said, "the first aim of Fianna Fail today is to secure, by agreement, the unification-of the national territory". On August 28 of that year, I said in response to the Downing St. declaration, "the Government agree that the border cannot be changed by force, it is and has been, their policy to seek the reunification of the country by peaceful means. . . Nothing must be left undone to avoid a recurrence of the present troubles, whether in five or fifty years, but to continue to ignore the need for constitutional change, so clearly necessary, could only have such a tragic result".

In Tralee a month later I said, "it will remain our most earnest aim and hope to win the consent of the majority of the people in the Six Counties, to means by which North and South can come together, in a re-united and sovereign Ireland, earning international respect for both the fairness and efficiency with which it is administered and for its contribution to world peace and progress".

At the Fianna Fail Ard Fheis on January 17, 1970, I said: "until the ugly blooms of mistrust and suspicion which poison the atmosphere have died and the ground is planted with the fresh, clean seeds of friendship and mutual confidence, reunification can never be more than an artificial plant, rather than a burgeoning, blossoming flower. And so I have said our course is clear: amnity not enmity, is our ideal; persuasion not persecution, must be our method; and integration not imposition, must be our ultimate method".

It is nearly 10 years since I uttered these words - they are as relevant now as they were then and I can repeat them with equal sincerity.

In the Garden of Rememberance speech of July 11, 1971, I said: "It would take nothing away from the honour of Britain, or the rights of the majority in the North, if the British Government were to declare their interest on encouraging the unity of Ireland by agreement, in independence and in a harmonious relationship, between the two islands" .

I have repeated these themes time and again throughout the last decade and it is therefore surprising to find them being taken as something radically different, or as some kind of new departure, when I reassert them. These themes are incorporated in the October 1975, Fianna Fail policy statement on the North which indicates that, until such time as the British Government declares itself in favour of the long term unity of Ireland and its commitment to implement a disengagement from the North, it should encourage the establishment of an agreed administration in the North, with devolved powers, which would be representative of both sections of the community.

In my Tralee speech and in a number of statements I made at the beginning of the 1970s and more particularly, in an article in Foreign Affairs, in June 1972, I indicated that we should contemplate constitutional and legislative change in the south in advance of any negotiations about unity, to encourage the Northern unionists, to look favourably at our overtures. However, the reaction to our removal of a section of Article 44 of the Constitution, which gave special recognition to the Catholic Church, was very discouraging. This initiative was completely ignored in the North as of absolutely no consequence, while previously, Northern loyalists had repeatedly pointed to this section, as evidence of the denominational character, of the southern state.

Shortly after the general election of 1973, and the Presidential election the same year, a Northern Ireland politician came to see me and I alluded to my disappointment with the Northern reaction to the constitutional change. He agreed it had almost no effect on Northern opinion. I then pointed out that we had just elected a Protestant President, asking if that had any impact on unionists. He replied that it had little, if any, but said that had we not done it, then there would have been a reaction. I appreciated then that it was futile making any constitutional changes in advance of unity and that any further changes, should be made in an all-Ireland context.

The IRA

I have also been bemused about Northern unionist suspicions concerning my personal attitude and that of my Government, towards the IRA. We have introduced a plethora of measures designed to clamp down on them, we spend very much more on security on a per capita basis, than does the British Government and we have repeatedly expressed our abhorrence, for all the IRA stands for.

By attempting to force a united Ireland on the Northern unionists, against their wishes, the IRA is acting not only contrary to what the vast majority of the people in the Republic and throughout the island would wish, but they are actually doing great damage to the cause of unity, which they allegedly espouse. .

There can be no unity through force or coercion - the unity we seek can come only through agreement and the IRA is making that unity, immeasurably more difficult.

This is quite apart from the revulsion which we all feel towards their repeated acts of barbarity. The catalogue of such barbarism over the last decade is long and agonising, but one incident sticks out in my mind more prominently than any other. This was the bombing of the Abercorn restaurant in Belfast, on Saturday, March 4, 1972. No warning of the bomb was given and two young women and 130 people were injured, many losing limbs and otherwise being maimed for life. One young woman lost both her legs and an arm and many others suffered similar injury.

I was absolutely appalled to realise that on this island, an organisation, claiming to act in the name of the Irish people, should perpetrate such an atrocity. What is the point of a united Ireland if this is the price to be paid for achieving it?

It was later that year that we passed the Offences Against the State (Amendment) Act, which empowered senior Garda officers, of the rank of Chief Superintendent, and higher, to state in evidence in court, their opinion on whether an accused was a member of an illegal organisation. That measure had a very significant effect on the IRA and it meant that for a while, leading members of the organisation, were safer in the North, than they were in the south. This was an indication of our determination to deal with the organisation, that has brought shame on all of us Irish people and I have really been perplexed by the doubts that have persisted about our determination, to wipe out the IRA, by all legitimate means, within the rule of law.

The 1973 Election

The debate on that Offences Against The State (Amendment) Bill, was the prelude to the calling of the 1973 general election. I was naturally very interested in the developments then within the main opposition party, Fine Gael, which was deeply divided on the issue. Quite obviously this would have been a propitious time for us to go to the country and offer ourselves as the alternative, to a deeply divided opposition.

However, I didn't want to curtail the debate on the Bill and it dragged on longer than I had originally assumed. It was my intention to call a general election immediately after the debate concluded, but this became impossible once the debate dragged on, because it would have had to be held either on Christmas eve, or the day after Christmas, neither being suitable for obvious reasons.

I was also anxious not to be seen to take advantage of the public outrage following the bombing of Dublin, on the evening of Friday, December 1, in which two busmen were killed and 83 people were injured. I therefore decided to wait until the new year before advising the President to dissolve the Dail and in retrospect, it must surely have been agreed that had circumstances permitted us to go to the country in the pre-Christmas period, we would have won the election.

In the event, we lost by a mere handful of votes. Had about 2000 votes spread throughout key constituencies swung to us, then we would have ended up with the two seat majority, instead of a two seat minority. In the event, I think that 1973 election result, was probably Fianna Fail's greatest electoral achievement with me as leader, although the party was the loser. We increased our total first votes by almost 24,000 and pushed up our percentage vote from 45.7 in 1969, to 46.2 - never before had a political party, or combination of parties, won such a high vote and lost the election.

The Arms Trial

Remember what we had been through over the previous 4 years. There was a time during that period, when it was widely believed we would be decimated at the polls, whenever an election took place. This was of course, due largely to the dismissal of ministers on May 6, 1970 and the resignation of another minister. Naturally this was a very trying period for me personally. Although I was not close socially to any of the people involved, I had grown up in politics with them and a bond of camraderie, had grown up between us. To have had to dismiss them from office was a very painful thing to do, as was the subsequent recrimination.

History will adjudicate on the rights and wrongs of that period, but I felt I had no option but to act as I did, given the information placed at my disposal, by the security forces. Kevin Boland has since accused me of felon setting in the prosecution of John Kelly, who was said to represent the Citizens Defence Committee, in Belfast. The fact however, is that I knew nothing of his involvement, until he was actually prosecuted. The initial information I received did not implicate him at all. After my abortive interview with Captain James Kelly, which arose from his telling the Gardai that he would talk only to the Taoiseach, I handed the entire papers in the case over to the Attorney General and he took it from there.

There have also been suggestions that I orchestrated the prosecutions throughout the affair, but again the fact of the matter is that I had no involvement whatsoever in anything to do with the prosecution, or with the conduct of the case, once I handed the papers over to the Attorney General.

Almost overnight in May of 1970, we lost four senior members of the Government - Charlie Haughey, Neil Blaney, Kevin Boland and Michael Moran. These were difficult ministers to replace, especially given the fact that a Taoiseach really has only a one in two choice, from which to make Government appointments. In the circumstances, I don't think we did badly, in spite of continued, opportunistic harrassment by the opposition. The growth rate for those years in the early seventies, was very high. We dealt competently with the security situation and we began to make substantial progress with the British, on a solution to the Northern Ireland problem.

The British

One of the difficulties I have experienced in dealing with British Prime Ministers or Ministers on the

One of the difficulties I have experienced in dealing with British Prime Ministers or Ministers on the

North, is that they often are not very well acquainted with the issue and don't rate it high in their order of priorities. This is understandable, given the relative importance of the Northern Ireland issue in the context of the overall British political situation, but it does mean that the Northern problem is allowed to drag on, sometimes unnecessarily.

I felt that we made a considerable breakthrough in our dealings with the British, in the autumn of 1971, when Mr. Heath, the then Prime Minister, acknowledged the legitimate interest of the Republic, in a solution to the Northern Ireland problem. We were making considerable progress, especially after the prorogation of Stormont, in March 1972 and the groundwork for Sunningdale was laid before we went out of office, in March '73.

Opposition

Because of the closeness of the 1973 election result, there was no talk about my going as party leader, not indeed did I feel myself that there was any need to consider retiring. However, when the Littlejohn affair arose in July '73, I felt that my position had been compromised to the extent that I should reconsider my position, as leader of Fianna Fail. It had quite escaped my mind that I had been informed that a junior British minister, had had some contact with the Littlejohn brothers before they came to Ireland - the information was passed to me almost as I was boarding a plane for America and I had simply directed that the papers be handed over to the relevant minister to let him deal with the matter.

I had begun to give my position some thought when I had the boat accident, in which my right heel bone was broken. I was in too much pain for several weeks thereafter to give resignation or anything else much consideration and when I returned to a party meeting, there was such an obvious flow of sentiment emphatically in favour of my carrying on, that I committed myself to leading the party into the following general election.

The question of resignation arose again following the west Mayo by-election in November, 1975. Our defeat was greater than we might reasonably have expected and I had to give some thought to my position. Again however, messages of support streamed in from all over the country and I was asked by a great number of backbenchers, to remain on. I felt it incumbent on me to stay, especially in the light of the commitment I had made just a year previously.

Back in Office

After the inevitable, initial dislocation when we went out of office, I felt that we formed ourselves into a forceful opposition and hammered home effectively, the short-comings of the coalition. Although some of the by-elections had not been encouraging, I nevertheless felt that the country was moving in our direction and it was no surprise therefore, to find ourselves back in office in July 1977, although the size of our Dail majority was certainly a surprise. In that election campaign, as I had done in the 1969 and the 1973 campaigns, I did an exhaustive and exhausting, tour of the country. These tours have now become part of the Fianna Fail electoral strategy and I think we have used them to good effect, even though they take a great deal out of a leader.

The great challenges facing the Government now lies on the job creation front and I believe that the election manifesto in itself, gave a great fillip towards the attainment of that objective, in that it created the kind of confidence necessary to generate investment, which in turn creates jobs. Our ambitious manifesto targets will not be attained this year, largely because of factors outside our control, notably the oil price increases and the industrial relations unrest. However, I think we have made an impressive start and so far 30,000 more jobs have been created since our coming into office - a record for the time span - and our growth rate, though depleted, remains one of the highest in Europe.

I think our successful negotiation of EMS entry and the negotiation of the National Understanding, have been major achievements of this Government. The EMS permits us to take part in a stable international monetary system, which is a precondition for investment, and the National Understanding, not alone secures a period of industrial calm, but mobilises the nation towards the attainment of our challenging, job creation goals.

The Northern Ireland problem still continues to be as intractable, as at any stage, in the last 10 years. It continues to be my primary objective to do whatever I can, to diminish the feelings of bitterness and antagonisms that pervade the two communities in the North and between North and South. If I feel, when I come finally to leave office, that I have done something to advance that objective, then I think my contribution as Taoiseach, will have been worthwhile.

MY SPORTING LIFE

I came on to the Cork senior hurling side during one of the county's leanest eras in the sport. Cork had won the 1931 All-Ireland title, but Limerick dominated hurling in Munster, for most of the rest of the decade.

I played with the Cork minors in the early thirties, but unfortunately, Cork were also then eclipsed in the minor sphere, by Tipperary. My first game with the senior team was in the 1935/36 season in the National League campaign against that famous Limerick side of that era.

Towards the end of the thirties, players of the likes of Willie Campbell, Alan Lotty, Jim Young, "Sonny"

Buckley and Paddy Donovan, came onto the side. We won the Munster Championship in 1939, but were beaten by Kilkenny by a single point, scored in the last minute of the final. That game was played in atrocious weather conditions and incidentally, the date was September 3, the day World War II began.

Although we were beaten by Limerick the following year in the Munster final, we knew we had an All-Ireland winning combination, especially with the advent of another Buckley (Dan Joe), and Christie Ring.

Ring was one of the most accomplished hurlers of all time and I would omit the qualification, were I not to know I would be accused of bias. He had supreme confidence in his own ability, refusing to be taken off a marker who may have been getting of him, feeling that he would turn the tables sooner or later. And so too he often did, but a remarkable burst of sheer excellence that would turn the course of a game.

He was by no means a mere hurling robot. He had a fine intelligence and marvellous perception. His contribution to Cork hurling and especially to the club, Glen Rovers, over 35 years as player and selector, was outstanding.

That defeat by Limerick in the 1940 Munster final, was the only defeat suffered for two seasons by the team and therefore, when we came to face Dublin in the All-Ireland final of 1941, we were firm favourites.

The team was a fine balance of young and experienced players. I played practically all my games for Cork at midfield, although I started at left half back and played a few times at right half forward. Towards the end of my career, when I was slowing down, I was moved to full forward. I was at midfield for all the All-Ireland finals, including our first victorious one, in 1941.

We played only one championship match before reaching the final that year. That was again against Limerick and this time we won easily by 8-10, to 3-2. I was playing well in that 1941 final, before first being injured and then being forced to leave the field. However, Cork won by a huge margin, 5-11 to 0-6 and Cork was set on a remarkable course, which was to yield four All-Ireland titles to the hurling side, in five years.

Dublin were our opponents in the 1942 final again. We had beaten Limerick by 2-14 to 3-4, in the Munster final and this time we beat Dublin by the less convincing margin of 2-14 to 3-4. In those days there were enormous transport difficulties because of the war. As in previous years, in 1942, several cycling parties set out from Cork on the Saturday before the final, stayed in Portlaoise that night and cycled on to Dublin the following day.

We met Antrim in the 1943 final and of the 48,000 people in Croke Park that day, at least 30,000 were hoping for an Antrim victory because of the fillip this would give the game, in the North. It was a disappointing match, largely because Antrim were suffering from stage fright and we ran out easy winners by 5-16 to 0-4.

In 1944, we were going for our fourth title in a row, which would have established a unique record in itself.

We beat Tipperary 1-9 to 1-3, Limerick by 4-6 to 3-6 and Galway 1-10 to 3-3, in what were all very tough games, on the way to the final. Nine of that Cork side had by now, won three All Ireland medals, myself being among them, so we were a very experienced side. The final was perhaps the easiest match of the championship that year

for us - we won over Dublin by 3-13 to 1-2.

We failed to get out of Munster in 1945, being beaten by Tipperary, who went on to beat Kilkenny in the final. However, I was fortunate in having another string to my bow that year, in being on the Cork football side.

I had played football with North "Mon." in college competitions and later with St. Nicholas, a sister club to Glen Rovers. Football however, was a very secondary interest for me, as indeed it was to Cork city in general, at the time. There didn't seem to be much prospect for Cork football in Leinster then, because of the preeminence of Kerry.

However, the breakthrough came in 1943, when we beat Kerry on a wet day in the Athletic grounds in the Munster final. We were beaten in the semi-final that year, by Cavan.

I transferred to Dublin shortly after this to continue my bar studies at the Kings Inns and I played football with Civil Service, when they won their first Dublin senior title. Through playing football with Civil Service, I began, really for the first time, to take football seriously and play in the company of players to whom football, was their only sporting interest. I think this helped me greatly in the game and because of this, I got onto the Cork side which beat Cavan in the 1945, All-Ireland final.

Cork owed their victory then to the fact that the team was backboned by the county champions, Clonakilty, and had in it, great footballers like: Eamonn Young, Jimmy Cronin, the late Weesh Murphy, Calet Crowe, Mick Tubridy and Gerry Beckett.

The hurling team came back in 1946, and won yet another All-Ireland, beating Kilkenny in the final by 7 -5 to 3-8, and by now I had attained the distinction of playing in six All-Ireland finals in a row and being on the winning side, in all six.

Indeed, I blame myself for failing to make that record seven ,for we reached the hurling final again in 1947, this time to lose to Kilkenny by a single point. I had the equalising of the game twice in the closing minutes, but hit wide on both occasions.

It was the end of an era.

My last competitive hurling game was the Munster Final in Killarney, in 1950, when Cork were beaten by Tipperary. My last football game was for St. Nicks, against the army, in the Cork County Championship, of 1951. I was then a Parliamentary Secretary.

I did play one other with Cork however. I attended an interparliamentary congress in Ottowa in 1952 and came home via New York. There I was persuaded by a former Glen Rovers man, Paddy Berry, to turn out for the New York Cork team. I was very unfit and overweight and was stiff and sore for weeks afterwards.

Like most other players, I have marvellous memories of my playing days, of team mates and opponents and of incidents on and off the field. Inevitably I made friendships, practically all over the country, and this, I suppose, helped me in the political sphere afterwards.

I think I learned from hurling and football a discipline and a self-control, how to be part of a team and how to cope with both victory and defeat. All players acquire these qualities in time, if they are to survive, and they apply well to life outside sport.