Indo-China: US Spreads the war

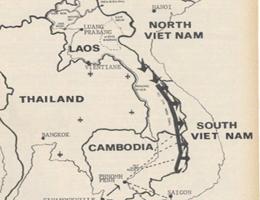

DESPITE THE prospect of further American troop withdrawals from Vietnam, it seems clear that American involvement in the area will continue long beyond any settlement reached in Saigon. Recent events in Laos, Cambodia and Thailand underline the American need for strong, vehemently anti-communist regimes in IndoChinese capitals. And Thailand, rather than Vietnam, is the lynchpin to this policy.

After the American refusal to sign the Geneva Convention of 1954which promised unification and free elections in Vietnam and the withdrawal of all foreign troops from IndoChina-Washington began to assemble an anti-communist military alliance to act as an umbrella for all areas not yet subject to Marxist governments. The centre for this alliance-SEA TO, or South East Asia Treaty Organisationwas Bangkok, the Thai capital.

The conversion of Thailand into an American garrison was perhaps facilitated by the unsophistication of national Thai politics. The French Empire never embraced Thailand, so that unlike other Indo-Chinese racial groups, the Thais did not experience the cohesive or educational effects of colonization. Furthermore, the gulf between the country-side and Bangkok meant that American intrusion did not provoke a popular rural opposition, since it did not significantly alter class relations.

CIA and Sea Supply

The advance of U.S. involvement was clear. In 1954, U.S. aid to Thailand totalled $8.8 million: the following year it was worth $48'5 million. The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency under the innocuous name of Sea Supply, trained the police force, and the Joint U.S. Military Aid Group trained the army. Yet the Thai politicians at the time were covertly anti-American. Newspapers that were their unofficial mouthpieces called for an alliance with China while they themselves made public noises in favour of the U.S. presence. One of the leading anti-American figures was Field Marshall Sarit Thanavat, a colleague of the present Thai leader, the then General Thanom Kittikachorn. Sarit was up for sale, however, and America bought him: he led a coup in 1957, with America's tacit approval. The following year, he led a second coup, a purge of all anti-American elements, and dissolved the National Assembly. Thailand was set irrevocably on the path of being a pawn in U.S. foreign policy. When Sarit died, it was found that he had milked the country of $100 million worth of U.S. aid.

Such corruption hardly matters to Washington, though, for the Bangkok government is host to the largest U.S. Air Force establishment outside America. From Thai bases, U.S. bombers have flown most of their raids on Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam. Thailand now has enormous numbers of political prisoners and a potent military whose dictatorship is reinforced by the presence of 40,000 American servicemen. The army has been doubled to loo,ooo-at the insistence of Washington-and its ration of police to population is I :400one of the highest in the world. American influence is ensured by the establishment and maintenance of a metropolitan caste of parasites which controls the government and enjoys the benefits of U.S. cash.

Thailand is thus a model for the U.S. policy in South East Asia which it has attempted to emulate in Saigon and Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital. In South Vietnam, the imprisonment of all constitutional opposition-by no means pro-communist-is proceeding apace. In particular President Thieu's personal vendetta against two of the most articulate members of the Assembly, Hoang Ho and Tran Ngoc Chau, has indicated the attitude of his regime. Ho has been sentenced to death and Chau to life imprisonment on ludicrous charges. Both men are ardent anticommunists, but are similarly antiThieu. Members of the Assembly commission appointed to investigate the My Lai massacre and which subsequently put the responsibility on Thieu were also imprisoned. The American government obviously is not too pleased with the image of Thieu's regime, yet they have not replaced him-as they surely could if they wanted. Since popular opinion towards the war is hardly likely to be altered by a change of personnel, Washington probably considers it best not to upset a government that does its job, however unsavoury it is.

Despite the great American success in Thailand and in Saigon, the war effort necessary to contain the various revolutionary movements in the area is limited by the needs of American internal politics. President Nixon is committed to some kind of withdrawal from Vietnam. With 100,000 less men still in Vietnam now than at the height of U.S. involvement, Nixon must stabilise governments favourable to him-Bangkok, Saigon-and shape some kind of subservience in two other governments, those of Cambodia (Phnom Penh) and Laos (Vientiane).

Cambodia

It seems most likely that the dethronement of Sihanouk as Cambodian head of State involved American support, active or merely tacit. Sihanouk is the kind of politician unique to S.E. Asia. Unprincipled and totally pragmatic, his capacity to slither in the correct political direction enabled him to maintain power variously as Premier, King-until he handed the throne to his father-and Head of State. His nimble antics, however, deprived him of any real base in higher circles. Thus he was unable to prevent the emergence of a class of military bureaucrats who nourished traditional anti-Vietnamese sentiments. This emergence was probably encouraged by the Americans who were antagonised by Sihanouk's indifference to the extensive use of

Cambodia by the North Vietnamese as sanctuary and supply route for the National Liberation Front. Though Sihanouk himself is not influenced by the racial animosities that characterise South East Asia, the Khmers who form a large proportion of the Cambodian population are activated by a distrust of Vietnamese. This is true particulary in Phnom Penh, where much of the business life is controlled by Vietnamese, many of them sympathetic to Hanoi. When Sihanouk went to France earlier this year, the opposition to the Vietnamese was growing and his opponents used his absence to strike. Well orchestrated anti-Vietnamese riots occurred in the capital and several provincial towns, with truck loads of demonstrators arriving to begin the festivities. What happened subsequently seems in retrospect to have been inevitable. Sihanouk was overthrown by his Prime Minister, Lieutenant-General Lon Nol and Deputy P. M. Prince Sisiwath Sirik Matak, and a courteous, even comradely note was delivered to the Vietnamese infiltrators demaning their withdrawal.

Sihanouk's overthrow was a blow to Hanoi. Much of the material used in South Vietnam by the N L F. came through the port of Sihanoukville in Cambodia, from Soviet ships. Sihanouk quite openly supported Ho Chi Minn throughout his life, and he attended his funeral. Furthermore, his was the second government to recognise the Provisional Revolutionary Governement of South Vietnam set up by the N L F. It is true that as part of his balancing trick, he had drifted somewhat towards the U.S. in recent 19 months, yet when the possibility arose of American troops intruding into Cambodia to pursue guerillas, Sihanouk threatened military action against them.

Benevolent neutrality from Hanoi

Hanoi is therefore championing Sihanouk. It is a piece of real-politik rather than revolutionary ardour. Hanoi in the past has given uncertain support for the communist movement in Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge. Now Hanoi wants to reinject stability -and benevolent neutrality-into the Cambodian government, to preserve Cambodia as a sanctuary for recuperant NLF troops and to ensure that Lon Nol-and more probably, Sirik Matak, do not become American puppets.

The early indications given by the new regime were ambiguous. The first note to the NLF was courteous-the next was not. U.S. forces are said to have made an excursion from Vietnam into Tay Minh province near the town of Krek to attack NLF positions. Even more ominous is the behaviour of the government to indigenous Vietnamese and pro-Sihanouk peasants (by no means a majority Vietnamese). At the end of March, demonstrators calling for the return of Sihanouk were massacred, and in Svay Rieng Pro.vince, next to the Vietnamese border, thousands of indigenous Vietnamese have been murdered by government troops. NLF forces have now encircled the province, and the military incapacity of the Cambodia army could throw the Phnom Penh government into American hands.

This is exactly what Washington wants. The overthrow of Sihanouk reeked of CIA interference. At his impeachment in the Assembly, Deputy after Deputy prompted by armed soldiers, rose to denounce him. The subsequent actions of the government, in particular, the return of the hijacked ship Columbia Eagle and the cal1 of the new government for international help against the NLF have done little to remove this impression. What the CIA is angling for is the closure of the great NLF sanctuaries in Cambodia: the picturesquely named 'Parrots Beak', 'Angels Wing', and 'Fishhook' salients along the Vietnamese border. What is more, the general extension of the war to Cambodia-through which some of the Ho Chi Minh trail passes-would mean both a dilution of Communist ground forces and expansion of allied strength. The United States presumably would willingly arm a militantly anti-Communist government in Phnom Penh, and such a government, with racialist overtones, has been installed. It is possible that Lon Nol would

attempt to strike a line independent of American whim, but clearly, the politics of neutrality are doomed in S.E. Asia. With the Americans prepared to mobilise racial (Le. antiVietnamese) animosities in their favour, it is most likely Cambodia will be drawn permanently into the conflict.

The invasion of Cambodia by 50,000 allied troops emphasises America's desire for victory rather than peace. However the great swathe of pillage and murder that marks the progress of American forces is more likely to help Communist recruitment than damage its war effort.

This will involve Thailand, too. Thai troops and aircraft have been used as 'mercenaries' in Laos by the CIAwhich is responsible for American military aid there. It is logical for the U.S. to pressure Bankok into greater troop involvement in Laos and probably Cambodia as well. This again would serve to reduce American commitment and re-inforce the identity of Bangkok with Washington. The prosecution of American foreign policy by satellite troops clearly is politically desireable. Sihanouk is still popular however; he has ruled for 30 years, nominally and otherwise, and he has almost become part of Cambodian folk lore.

Laos

In Laos, another of the great 'Princes has found his power threatened. Prince Souvanna Phouma, the Prime Minister, is caught between two fires: the communist Pathet Lao, who control most of the north of his country, and his own right wing, probably assisted by the ubiquitous CIA. Only someone as light as foot as he could have avoided political incineration for so long, and his dilemma reveals the bankruptcy of neutralism in a subcontinent that is now torn by bloc polarisation.

Souvanna Phouma has a reputation for cunning second only to Sihanouk. Up until the Geneva Convention of 1961 he (as neutralist leader) and the Pathet Lao were working against the right wing government of Boun Oum. The political settlement then reached al10wed for a coalition government of neutralists, the right wing, and the Pathet Lao, the political wing of which, the Neo Hak Xat, was (and still is) led by Souvanna's half brother, Prince Souphanouvong. The Pathet Lao were driven out of the coalition in 1964 by the other two factions, and held fast in the North Eastern section of the country allocated to their authority at Geneva.

Last year, government and CIA trained Meo tribesmen took over the Plain of Jars, part of the Pathet LaC) 'franchise'. Earlier this year, Souvanna Phouma's men were driven out by regrouped Communist forces, who are. now in absolute control of Sam Neua and Xieng Khouang provinces, and are able to strut the length and breadth of the whole Northern region -including the royal capital, Luang Prabang, and the governmental capital, Vientiane. The ease with which the Communist forces reasserted their might must cause some concern to Washington, which already is committed to supplying a large amount of air-power in defence of Souvanna Phouma.

General Tion Sayavong, military commander of Luang Prabang, has claimed the Pathet Lao's next stop would be the invasion of the royal capital. Until the deposition of Sihanouk, this was unlikely. The North Vietnamese and Pathlet Lao retook the Plain of Jars when Sihanouk's policy of neutralism appeared to work. One of the aims of the Pathet Lao was probably to force Souvanna Phouma into a neutralist position. A second neutral power was probably a viable prospect then. With Cambodia drawn into the conflict, there could be no prospect of an independent Laos. So while Peking and Hanoi are industriously trying to recrown Sihanouk they must face the fact that neutralism in Laos is doomed. By overthrowing Sihanouk the Americans have probably forced the communists into a more extreme position in Laos. Hitherto, the Pathet Lao have shown great respect to the Laotian king in their policy statements. His overthrow must now be on the cards. Nevertheless, the North Vietnamese Politburo is peopled with diplomats, and the demands of the Pathet Lao so far indicate the desire for a negotiated settlement. These basically, are (i) ceasefire; (ii) demilitarised zones for negotiations; (iii) an all party conference to prepare for a provisional coalition; (iv) free elections. The precondition for these is that American bombing should stop.

Probably a strong factor in the changed situation in Laos is the reemergence of China as the main supplier of guns and morale to the North Vietnamese. Till recently, this position was held by the Russians. The Kremlin, however, is now taking a very conciliatory position towards the U.S., and despite the supposed influence of the Moscow oriented Le Duan in the Politburo, North Vietnamese dependence on China has grown. Much of the Russian aid came to Sihanoukville in the Gulf of Siam. From there it was transported by a Cambodian-Chinese truck firm to infiltration points in South Vietnam. Now, however, the majority of infantry weapons are coming overland from China. This explains the increased importance of the Ho Chi Minh trail and the North Vietnamese desire to maintain its viability. In March this year, some 45,000 trucks used the trail, as opposed to 10,000 during the great Tet offensive. An offensive in Laos could possibly therefore be no more than an attempt to defend the supply route. If, as the Pathet Lao demanded, all bombing were stopped before any talks began, it would greatly facilitate the transport of supplies along the trail.

Finally, and perhaps most effectively, the Pathet Lao have revealed the bankruptcy of Nixon's policy of 'Vietnamisation.' Their almost laconic display of military prowess has shown that even if the U.S. manages to field a South Vietnamese army capable of fighting the NLF, it must also pacify Laos before it has any meaning. Of course, America is acutely aware of strategic importance of Laos. It is, in fact, an ersatz state, a political convenience for international powers, consisting of a racial conglomeration of Lao, three Thai groups (called Black, White and Red), Vietnamese, Meos and Khas. Its capital, Vientiane, is unknown to most of its population. U.S. aid is worth $250 million a year, though Vientiane's nominal subjects only total three million, and its real ones a fraction of that. The American political observer, Arthur Dommen, has calculated that only t% of that aid reaches the agricultural sector, which involves 95% of the people. Since 1959, the Royal Laotian Army (RLA) has been under the supervision of yet another CIA front, the Programs Evaluation Office. There are also an unknown number of Special Forces in the area: Time magazine admits that the 2,350 registered Americans claimed by the Vientiane embassy is probably far short, although unlikely to be as high as the 15,000 claimed by Hanoi.

The most effective corps in the RLA is the CIA trained Meo tribesmen. Pursuing the line already profitable in ViC'tnam, where Montagnards have been armed against the Viet Cong, in Laos the CIA have trained some 10,000 Meo soldiers. Strangely enough their brother Meos in Thailand are so far the most coherent popular opposition to emerge against the Americans. The rest of the Laotian armyaround 60,000 men-is comically ineffective.

There are up to 100,000 Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese in Laos. Hanoi's attitude to Laos is that it is no more than an accident of real estate, has no cogent claims to statehood, that it is historically linked with Vietnam and only prevailing political circumstances prevent a lasting solution. Hanoi therefore treats Laotian frontiers with scant respect. The extension of the Ho Chi Minh trail into unpopulated-or where U.S. bombers have been, depopulated-areas makes the write of Vientiane something of a rural joke.

Considerable emphasis has been put on the road building at present going on in northern Laos. From the Yunnan Salient of China to Muong Soui, the Chinese army built a road, at the request of Vientiane. However, from Muong Soui, illegal roads are being built to Pak Beng, on the Mekong River and near to the Thai border, and to Dien Bien Phu in North Vietnam. It seems possible therefore that the North Vietnamese are building these roads. This would be consonant with China's role as main supplier of small arms. It would also increase communications between Hanoi and those Vietnamese living over the Mekong River in Thailand who are said to be sympathetic to Hanoi. Bangkok sources have claimed that units of North Vietnamese soldiers have already entered Thailand although this is extremely unlikely.

Prospects for the future

The seepage of Communist influence into Thailand through Laos is a predictable step for Hanoi. Thailand is too pivotal to American involvement in S.E. Asia for it to rC'main unmolested. Thai troops have already moved to the frontier, and Marshall Kittakachorn, the Thai Prime Minister, is seeking even more arms from the U.S.

America's desire for a military solution to the South East Asia question precludes any idea of a peaceful settlement. It was the U.S. that broke the Geneva Convention of 1961 when it considered it worthwhile to, and presumably, any other settlement would be acceptable only as long as it was profitable. The eclipse of General Giap, the architect of the battle of Dien Bien Phu and the Tet offensive, in the North Vietnamese Politburo led to the fervent espousal of the cause of neutrality in Cambodia. Now that the U.S. apparently wishes to spread the war-zone into that country too, Hanoi will be forced into a more instransigent position. Although Sihanouk has been courted by Moscow, Peking, Hanoi and the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam, their support for him will go on only so long as there is general support for him in Cambodia and a chance to re-establish him. If not, then it may be assumed that guerilla warfare will be started in Cambodia too. American pressure on Phnom Penh since Sihanouk's downfall has been light: it will not be long before she puts the boot in.

Yet Nixon is limited by a troubled economy and a suspicious Congress. American policy clearly is to arm mercenaries to fight her battles for her. Already the United States has drawn in on its shirt tails Australians, New Zealanders, Thais, Philippinos and South Koreans. The cynicism of this recruitment is typified by the deal done with the Phi Ii pine Government: cost plus S50 million for the troops involved. Dead Philippinos-or live ones for that matter-don't have Congressmen in Washington. Furthermore the South-Vietnamese army is at present losing 800 killed a week in defence of a government that only Washington wants.

While the United States must force political and social stabilization in this respective area if they are to prevent the emergence of an articulate power-group willing to capitulate to some Communist demands, if it overreaches itself, it could provoke Chinese intervention. Though part of the U.S. military is itching to blast China back into the Stone Age-as Curtis Lemay, the former USAF chief once put itit would be political suicide for Nixon. He has long since jettisoned principle [or the politics of expediency, and the sinister manipulations of the CIAwhich are beyond the call of the ballot-box-have probably been given greater licence than ever before. Furthermore, American air power in the region is as great as ever it was. It seems the intention of Washington that Asian peasants should be subject to the governments of its choosing for some time.