IFA: Stormy Weather and Divided Ranks

An agreed IFA position on taxation and the coming merger with ICMSA seem to demonstrate the growing strength and unity of the farmer organisations. But there are troubles ahead: farm incomes are under pressure and next year's IFA elections have opened a serious rift already.

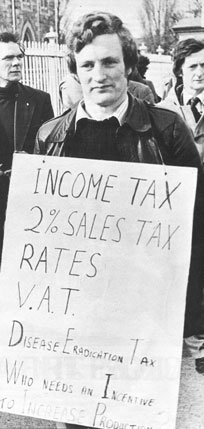

Jim Gibbons took some early precautions. Soon after he moved into Mark Clinton's seat, he let it be known that farmers' interests came first, even if that meant conflict with Fianna Fail. When George Colley announced the 2 per cent sales levy last February, the Minister for Agriculture suggested to a reporter that he had nothing to do with it and successfully avoided the subsequent flak.

Ministers for Agriculture have since Ireland's entry into the EEC become Ministers for Farmers, but they are also at the mercy of the farmer organisations. The farming vote has settled into a regular pendulum pattern, and it can now largely determine not merely the fate of individual agricultural ministers (watch out for Gibbons in the re-shuffle) but also the fate of governments.

Jim Gibbons and Mark Clinton have represented a sectional interest in a way which is unthinkable for, say, ministers of Labour, Health or Industry and Commerce. But inevitably, differences can, and do arise. Just now, they are arising rather frequently. The editorials and commentary in the Farmers' Journal mark the end of the honeymoon period. The paper, which is the unofficial organ of the Irish Farmers' Association, condemns "leadership inertia" - including Fine Gael's John Bruton in the swipe. And an editorial in the Journal recently suggested that "his advisors should tell the Minister for Agriculture, Jim Gibbons, that we now live in late 1979."

Jim Gibbons and Mark Clinton have represented a sectional interest in a way which is unthinkable for, say, ministers of Labour, Health or Industry and Commerce. But inevitably, differences can, and do arise. Just now, they are arising rather frequently. The editorials and commentary in the Farmers' Journal mark the end of the honeymoon period. The paper, which is the unofficial organ of the Irish Farmers' Association, condemns "leadership inertia" - including Fine Gael's John Bruton in the swipe. And an editorial in the Journal recently suggested that "his advisors should tell the Minister for Agriculture, Jim Gibbons, that we now live in late 1979."

Some of the cut and thrust is for public (party-political and IFA membership) consumption. The atmosphere at the two or three meetings per month between IFA delegations and ministers or department staff is generally friendly and business-like. Paddy Lane and his fellow Clareman, Sylvester Barrett, were happy to play a round of charity golf together last month - and Barrett was even happier to win. The new, aggressive tone of public statements is a clear indication that the pre-Budget negotiations on the thorny question of farmer taxation are about to begin.

The new tone also reflects what is being called, in the current catch-phrase of farmers' leaders, a "crisis of confidence". A number of problems rolled together at once has produced not only a hint of panic in political relations but also a very tangible effect on farm production. In 1979, for the first time in many years, total output from Ireland's farms is likely to drop. The honeymoon with the EEC is also over.

Asked to explain the deterioration of relations with the Minister, IFA President Paddy Lane is vague: farmers have faced stop-go policies on taxation for too long, he says; we need to have discussions between the four social partners - farmers, employers, government and unions - to determine the nationally agreed place of agriculture in the economy and, on that basis, establish a fair code of taxation. But he is unable to say precisely what he thinks the Minister should do at present.

Neither Jim Gibbons nor the government as a whole have much discretion over many of the problems affecting agriculture. The direct lobbying of the minister is become increasingly irrelevant, as the big battles leading to a slow-down in the rise in farm prices, or changes in commodity policies are played out at European level. The IFA has itself played a large part in streamlining farmers' representation in Brussels, and in internationalising the representations made to the agriculture ministers in each EEC member-state. But the personal assault on the minister in Dublin is what the members expect.

That public relations brinkmanship may get the IFA into difficulties. Since Paddy Lane became president and Joe Rea became vicepresident in 1976, the IFA has become noisier, their approach more assertive. The internal worries this has caused are reflected in the line-up for next year's presidential election in which Joe Rea is likely to be competing with Donal Cashman.

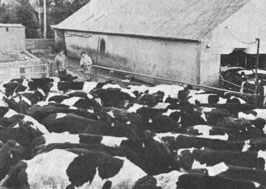

To many outside, it has seemed as if the IFA continued a chorus of complaints even when farm incomes were rising comfortably ahead of inflation. Even now, they are exaggerating the decline in dairy farming resulting from slower price rises. Total applications for grants under the EEC's Dairy Herd Conversion Scheme - an incentive to move farmers out of milk production in which there is in the EEC a nearly 20 per cent surplus - have certainly increased. But they still represent just over 1 per cent of all dairy farms in the state, a proportion for which natural wastage might largely account.

Now that farmers are really heading into more troubled times, they could find that they are suspected of crying wolf yet again. Their position is also weakened by the difficulties which they have in achieving agreed policies on several of the crucial issues, and by the apparent double standard affecting some of those positions.

On taxation, the allegation of "stop-go" made against successive ministers would apply with equal force to the farm organisations. Only at the end of September, after a round of county discussions on a document produced by the IFA's taxation committee, did that organisation decide a policy. It was not done easily, as differences emerged between senior officers of the organisation, as well as between them and some of the county executives. Days before the IFA National Council was due to discuss the tax document and amendments, Paddy Lane could give only a very general outline of what might be decided: taxation on accounts, with an option for the more intensive farmer to pay the average rate plus a surcharge rather than be taxed on full accounts.

Lane acknowledges, however, that the IFA's resistance to the proposed 2 per cent sales levy proposed in this year's budget may have been misunderstood as resistance in principle to any taxation. His own position on the evening of the Budget was that the farmers would be willing to contribute the amount which Colley was aiming to collect from the sales levy, but they would not accept that particular method of collection. Within days, however, a serious rift emerged between Lane and his normally close deputy, Joe Rea. While the president was in Brussells the vice-president prepared for a massive picket on the Fianna Fail Ard Fheis. On his return, Lane scaled it down. By the Ard Fheis weekend, the point had been made with force and Colley started the retreat.

Subsequent talks between the government and the farmer organisations failed to produce an acceptable alternative, so, with the sales levy in force, the IFA has turned to the courts, confident that it can have the scheme declared illegal under provisions of Ireland's EEC membership. While that challenge continues, Paddy Lane is also insisting that Col1ey's stated target of a £100 million farmer contribution to state revenue through taxation is unrealistic. It is based, he says, on income projections which later rises in prices of oil, feedstuffs, fertilisers, as wel1 as reduced yields from some commodities, have made academic.

Although Jim Gibbons has avoided the flak on the tax issue he is personally involved in rows with the farm organisations over disease eradication and calf exports. On both, he has taken a firm line: the waste of public funds caused by systematic circumvention of TB and brucellosis eradications schemes has got to stop; the export of calves, from which some farmers are making short-term gains, can only have a damaging effect on the national herd and the longerterm future of the livestock industry.

On both scores, Jim Gibbons and the EEC behind him - has supporters in the ranks of the IFA, right up to National Council and subcommittee chairman level. But the current style of IFA leadership leaves no room for farmers to admit publicly that they may not always have been right. When Co. Wicklow farmer Alan Gillis stated, as chairman of the IFA's Animal Health Committee, that farmers had to take some of the blame for the failure of the £250 million disease schemes, he was left standing on his own by the National Council. Although it is widely recognised that switching of ear-tags and the sale of animals known to be infected have undermined the several programmes aimed at clearing the state, county by county, of the two main cattle diseases, the IFA's senior officers and National Council could not accept that it was any part of their function to acknowledge this in public. Gillis resigned his committee position and only resumed it after much persuasion.

On both scores, Jim Gibbons and the EEC behind him - has supporters in the ranks of the IFA, right up to National Council and subcommittee chairman level. But the current style of IFA leadership leaves no room for farmers to admit publicly that they may not always have been right. When Co. Wicklow farmer Alan Gillis stated, as chairman of the IFA's Animal Health Committee, that farmers had to take some of the blame for the failure of the £250 million disease schemes, he was left standing on his own by the National Council. Although it is widely recognised that switching of ear-tags and the sale of animals known to be infected have undermined the several programmes aimed at clearing the state, county by county, of the two main cattle diseases, the IFA's senior officers and National Council could not accept that it was any part of their function to acknowledge this in public. Gillis resigned his committee position and only resumed it after much persuasion.

It is the strength of the dairy lobby in the IFA - and, even more obviously in the Irish Creamery Milk Suppliers' Association, with which it will be merging next year which makes these organisations acquiesce in the current high level of calf exports. These keep up the prices of calves which the dairy farmer is selling, but they reduce the margins for the beef farmers, notably for the (usually) smaller farmer raising calves to store level. Gibbons's measures to limit calf exports took effect earlier this year and they have added nothing to his popularity with the most powerful farmers.

The slow-down in farm price rises is more a function of the EEC Commission's increasing difficulty in raising the finance to support the present structure of agricultural prices than it is of the growth of the consumer and trade union lobbies' influence in Brussels. Nonetheless, it takes place against a background of growing scepticism about the value of the Common Agricultural Policy. It presents the farmer organisations therefore, with new challenges to justify this costly scheme to workers who are beginning to resist actively the burden of taxation which is put on them partly in order to finance that scheme.

Faced with that very considerable challenge, the crisis of confidence in agriculture, the differences with the Minister for Agriculture already mentioned, as well as a likely battle on his Land Bill of next year, the IFA farmer organisations are clearly in need of decisive and coherent leadership. The merger with the ICMSA will add another 60,000 members to the IFA's present 150,000 and prevent future Agriculture Ministers using the differences between the two organisations to defer decision. The Irish Farmer's Union, as it is likely to be called, will also have increased centralised resources to further improve the effectiveness and efficiency of farmer representation. This should herald an era of even stronger, more concerted lobbying by what is already the country's most effective lobby. In the choppy waters ahead, farmers would seem to need just that boost. But there are a few more cross-winds, some blowing within the IFA, some blowing without.

The leadership of Lane and Rea has spawned widespread political (though not party-political) controversy within the organisation. For many months - and long before nominations have been declared for next year's presidential and vicepresidential elections - the organisation has divided into factions along the lines of the presumed candidacies for those elections. It is widely accepted that the presidential contest will be a race between Joe Rea and Donal (Donie) Cashman, current honorary secretary and chairman of the taxation sub-committee, and that their respective running mates will be Pat Dunne, of Cork (chairman of the Pigs Committee), and Alan Gillis.

The leadership of Lane and Rea has spawned widespread political (though not party-political) controversy within the organisation. For many months - and long before nominations have been declared for next year's presidential and vicepresidential elections - the organisation has divided into factions along the lines of the presumed candidacies for those elections. It is widely accepted that the presidential contest will be a race between Joe Rea and Donal (Donie) Cashman, current honorary secretary and chairman of the taxation sub-committee, and that their respective running mates will be Pat Dunne, of Cork (chairman of the Pigs Committee), and Alan Gillis.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to discern any significant differences of policy between the two camps. They part on matters of tactics and style. Some of that gap is already apparent from the Gillis resignation. It comes down to two views of the organisation as either a "trade union", which is aggressive and willingly raises antagonisms with governments and other sectional interests (as in last month's statement from Paddy Lane on threatened power cuts), or as a "business organisation", which reasons and documents its case more carefully.

The internal regime of the IFA changed with Paddy Lane's election to the presidency - so much, indeed, that it has produced converts to the Cashman camp. Lane brought to the post the confidence and discipline bred by three years on an Army cadet course; he wanted to encourage alertness through more rapid turnover of staff. The organisation's resources were increasing steadily and this made it possible to add fifteen technical advisors and field officers to the staff in little over three years. In the same period, a dozen senior officials have left and, since the resignation of the former deputy secretary, Richard Hourigan, a couple of county executives have been insisting they should know the reasons for the resignations.

In IFA headquarters, however, Hourigan, who has returned to farming in Co. Limerick and has set up an estate agency, is suspected of stirring up this discontent. He had hoped to become chief executive after the resignation of Sean Healy, secretary of the IFA/NFA, since the foundation of the organisation in 1955, and secretary of Macra na Feirme before that. Hourigan is a first cousin of Paddy Lane, which has added to the complications. Sean Healy's earlier resignation was surrounded by controversy too. He had been in bad health and this was given as a reason to replace him, but several of the senior elected officers made no secret of their desire to see him moved aside.

Healy was replaced by Michael Kehoe, one of a pair of identical twins who have been in and out of a number of executive posts and management consultancy. The Agricultural Relations Bureau was set up in the Farm Centre to provide Healy with a well-paid sinecure. Its jargonridden statement of aims talks of "optimum achievement of purpose", "ongoing review" and insists that "an era of meaningful, constructive negotiation (between rural and urban communities) ... must be made to evolve." But it has made little or no public impact.

The round of resignations causes Paddy Lane no discomfort; indeed, he draws satisfaction from the success of former IFA officials in landing top positions in agri-business: Lorcan Blake as agricultural adviser to Allied Irish Banks and Billy Murphy and Eugene Brennan as advisers to the big Avonmore (Co. Kilkenny) Co-op. The IFA staff is exposed to the public, he points out, and these successes point to the organisation's ability to choose people who stand that test well. The turnover could well be more rapid, he says, and it is possible that the Co. Donegal executive, which raised questions about the resignations, might not be aware of the current level of staff and the inevitable turnover that it produces. However, Co. Donegal is not alone in its concern. When a Donegal resolution seeking a committee of inquiry appeared to have been shelved, the Co. Dublin executive sought to have it re-activated. But no inquiry is taking place.

The round of resignations causes Paddy Lane no discomfort; indeed, he draws satisfaction from the success of former IFA officials in landing top positions in agri-business: Lorcan Blake as agricultural adviser to Allied Irish Banks and Billy Murphy and Eugene Brennan as advisers to the big Avonmore (Co. Kilkenny) Co-op. The IFA staff is exposed to the public, he points out, and these successes point to the organisation's ability to choose people who stand that test well. The turnover could well be more rapid, he says, and it is possible that the Co. Donegal executive, which raised questions about the resignations, might not be aware of the current level of staff and the inevitable turnover that it produces. However, Co. Donegal is not alone in its concern. When a Donegal resolution seeking a committee of inquiry appeared to have been shelved, the Co. Dublin executive sought to have it re-activated. But no inquiry is taking place.

The transition from T.J. Maher as President to Paddy Lane brought a brasher, more thrusting style; the possible change-over to Joe Rea - puritanically dedicated to becoming a successful farm leader - would accentuate that even further. Rea has been a very pushy vice-president, often appearing to hog as much of the publicity as Lane, and, on occasions, to have more influence on policy. Since he defeated Cashman comfortably for the vice-presidency, he has travelled the country extensively to attend county meetings, almost as if he had started a presidential election campaign the day he took the deputy position. Rea is abrupt and brusque but, through his "Milk League" column in the Farmers' Journal, in which he compares prices being paid by different co-operatives, very popular.

That column emphasises a second tangle presenting itself to the IFA. Its criticism of the co-ops can hardly be expected to warm the cockles of T.J. Maher's heart. But as president of the Irish Co-operative Society, and now as member of the European Parliament, Maher has retained considerable influence in Irish farming circles. Few inside, and even fewer outside, farming can recall that Jerome Buttimer was his predecessor as president of the lAOS, as it then was. The organisation was moribund. With the increasing concentration of power among the top ten agri-business coops, the "movement's" co-ordinating body hardly seemed to have a function.

Before the end of his term as IFA president, T.J. Maher was drafted on to the lAOS Council although he had no base in any particular co-op. Maher had no difficulty in being elected president of the organisation and subsequently being re-elected to the post with increased support. A new broom was applied to the lAOS headquarters, Plunkett House, just across the road from Government Buildings. A study commissioned from the Irish Management Institute produced new internal structures. A chief executive was appointed - John McCarrick, former agricultural adviser to the Bank of Ireland. And the flow of public statements from McCarrick and Maher on current farming controversies increased steadily.

It is doubtful if the co-ops needed ICOS very badly; two of them don't pay any subscriptions. The ICOS document, Framework for CoOperative Development, has not found unanimous support. But a personal vehicle for T. J. Maher has been created - and possibly a platform for future IFA presidents when they end their term. However, while Paddy Lane describes the ICOS as an additional focus of farming representation, he can also see its danger as an alternative focus, even though there is considerable overlap in the two organisations' council membership.

Maher has underlined his difference with Lane's chosen successor, Joe Rea, by taking a delegation to the Minister for Finance to discuss the pig industry at a time when Rea was leading a picket on Government Buildings on the same issue. Maher's delegation came to the Minister's office from Leinster House, protesting later that they had seen no picket!

Maher's campaign for the European Parliament and even more his election with a very impressive majority caused ripples through the IFA and its headquarters, the Irish Farm Centre. The IFA had decided, after some discussion, to stay out of the elections, but Maher's confirmation that he was running came late. Paddy Lane's proposal to the National Council was that they should not stop any individual members working for Maher, but that they could not give the IFA's blessing to his campaign. In the event, IFA members in every part of the Munster constituency - and from as far away as the Inshowen peninsula in Co. Donegal - were active in the campaign. Even the one member of the IFA Council of 1973 who had opposed entry into the EEC - Joe Dunphy, from Co. Sligo - swung into the campaign. But, privately, some of the leading figures in the Farm Centre, notably Paddy O'Keeffe, editor of the Farmers' Journal, were expecting, and perhaps hoping, that Maher would do badly.

Maher's campaign for the European Parliament and even more his election with a very impressive majority caused ripples through the IFA and its headquarters, the Irish Farm Centre. The IFA had decided, after some discussion, to stay out of the elections, but Maher's confirmation that he was running came late. Paddy Lane's proposal to the National Council was that they should not stop any individual members working for Maher, but that they could not give the IFA's blessing to his campaign. In the event, IFA members in every part of the Munster constituency - and from as far away as the Inshowen peninsula in Co. Donegal - were active in the campaign. Even the one member of the IFA Council of 1973 who had opposed entry into the EEC - Joe Dunphy, from Co. Sligo - swung into the campaign. But, privately, some of the leading figures in the Farm Centre, notably Paddy O'Keeffe, editor of the Farmers' Journal, were expecting, and perhaps hoping, that Maher would do badly.

Now that Maher is safely installed in Strasbourg and has become a member of the Agricultural Committee, which includes former farm organisation leaders from several other European countries, the IFA has to depend on him to some extent. COPA, the EEC-based confederation of farmer organisations, has been quick to set up relations with the Agricultural Committee, in order to back up its frequent direct representations to the Commission. And the IFA plays a prominent role in COPA, Paddy Lane currently being a senior vicepresident. Just to complete the circle, TJ. Maher is president of the EEC agricultural co-operatives body, COGECA, until December and both Maher and Lane are members of the EEC's Economics and Social Committee. Even though his additional European commitments remove him from the Irish scene more than before, it is unavoidable that Maher should have some direct or indirect influence on the IFA elections next spring. And that influence is in support of Donie Cashman.

The problems which farmers and their organisations are facing should not obscure the IFA's remarkable successes. In the expansion of the organisation to its present level, with a staff of 80 and an annual expenditure of over £1 million, the IFA has succeeded in avoiding two rifts to which it might well have been prey: division along party lines and division between small and big farmers. All attempts to organise farmers as one single lobby up to the 1940s had broken down on party rows. So, the young farmers' organisation, Macra na Feirme, set up in 1944, had the explicit aim of keeping out of political and economic controversy. So persistent was the flow of requests for action on such matters, however, that Macra took the initiative in calling together all farm bodies for a convention in Dublin's Four Provinces Ballroom in January 1955 to form the National Farmers' Association. Notably absent was the recently formed ICMSA. Many of its earliest leaders had to pass on before the way could be cleared for the even tually successful unity negotiations of this year.

The county organisations of the IFA include many who are activists either of Fianna Fail or Fine Gael. Inevitably, elections may be decided on party loyalties. At one time, indeed, Fine Gael appears to have made a concerted - though unsuccessful - effort to win key positions throughout the organisation. Nationally, however, the IFA has succeeded in keeping outside and above party divisions, enhancing its ability to play one off against the other. After he had achieved prominence in Macra, Joe Rea was widely expected to run for Tipperary county council as a Fine Gael candidate; but the party's old guard in the county wanted nothing of it. Paddy Lane has family connections in Fine Gael, but when he was being tipped to run for election it was thought that he might represent Fianna Fail. Former NFA president, Rickard Deasy, was one of the few NFA/IFA leaders to make a public option for a political party; his choice of Labour was singularly misguided.

It is striking, too, that none of the current or recent strains within the IFA reflect big v. small. From the outside, the IFA has always appeared to be essentially a big farmer organisation. The description is accurate in so far as its leading officers have always been farmers of 100 acres or more. But farmers of much smaller acreage play an active role in the organisation and are increasingly involved in county and national committees. The much-abused Sean Lemass dictum that a rising tide lifts all boats applies with some force to the farming population. And, with greater prosperity, and some blurring of the lines between different strata of farmers, the smaller-acreage farmers have been in a position to play a fuller part in the IFA's affairs. The IFA itself has also benefited from the rising tide. It can now afford to pay expenses to delegates at committee and council meetings, so less well-off farmers who would previously have lost heavily by taking national office can afford to do so.

It is striking, too, that none of the current or recent strains within the IFA reflect big v. small. From the outside, the IFA has always appeared to be essentially a big farmer organisation. The description is accurate in so far as its leading officers have always been farmers of 100 acres or more. But farmers of much smaller acreage play an active role in the organisation and are increasingly involved in county and national committees. The much-abused Sean Lemass dictum that a rising tide lifts all boats applies with some force to the farming population. And, with greater prosperity, and some blurring of the lines between different strata of farmers, the smaller-acreage farmers have been in a position to play a fuller part in the IFA's affairs. The IFA itself has also benefited from the rising tide. It can now afford to pay expenses to delegates at committee and council meetings, so less well-off farmers who would previously have lost heavily by taking national office can afford to do so.

The IFA leadership has come mainly from the dairy belt of North Munster; the two likely candidates for the next presidency represent that area, too. The first NFA president, Juan Greene, comes from a family with one of the largest tillage farms in Europe. The leaders who camped on the steps of Government Buildings in the 1960s, and some of whom went to prison in that "Farmers' Rights Campaign" were, for the most part, dairy, livestock or tillage farmers on very substantial holdings.

More recently, however, it is small farmers from Roscommon and Leitrim who have picketed the Dail - as, for instance, over the 2 per cent sales levy. They have done it, not in the name of some independent small farmers' organisation, but on behalf of the IFA. In a recently published study of small farmers from that region, Damian Hannan, of the Economic and Social Research Institute, notes that participation in voluntary organisations and in the mass media is low, but that it increases very significantly among the younger farmers. The best-attended meetings of the IFA take place in kerry and Clare, two counties where farms are below the average size; Mayo is one of the best-organised IFA areas in the country, and the first to respond to a recently introduced IFA marts levy. The refusals to pay up came from areas east of Roscommon.

For some years, there has been pressure on the IFA leadership to recognise the particular problems of small farmers in the West. Paddy Lane's response was to have a convention organised in Salthill last year. As a result - and against some opposition within the organisation - a Western Development Committee was set up. Within COPA, the IFA has pressed successfully for the problems of the West to be given special recognition. After three years of lobbying by COPA, the EEC Commission has given that recognition to southern Italy and the West of lreland.

For some years, there has been pressure on the IFA leadership to recognise the particular problems of small farmers in the West. Paddy Lane's response was to have a convention organised in Salthill last year. As a result - and against some opposition within the organisation - a Western Development Committee was set up. Within COPA, the IFA has pressed successfully for the problems of the West to be given special recognition. After three years of lobbying by COPA, the EEC Commission has given that recognition to southern Italy and the West of lreland.

None of these achievements change the picture substantially, says Dan McCarthy, president of the National Land League. If there are problems facing all farmers as a result of pressure on farm prices and inflation for inputs, then those problems affect the 60,000 farmers on 30 - 80 acres particularly severely. The accumulating levies which farmers pay have led, he says, to special hardship for smaller farmers. The collapse in the price of store cattle hits them hard, too.

The bulk of farm production still comes from farms between 30 and 80 acres but the rate of increase in output is also slowest in that bracket. At the same time, the virtual halt to land purchases for re-distribution by the Land Commission means that the re-structuring of agricultural holdings which has gone on slowly over the past 50 years is actually decelerating.

From his own experience, however, McCarthy is the first to acknowledge the problems in organising small farmers independently of the IFA, ICMSA or even as a caucus within those organisations. The first problem, he says, is finance, but the aspiration of most small farmers to become big farmers, arid their willingness to entrust their interests meanwhile to those who have the staff on their farm, the education and the ability to represent them effectively add to the obstacles. The National Land League has about 1,000 members who attend branch meetings. The Small Farmers' Association has all but disappeared.

Between 1965 and 1975, the number of holdings between 50 and 100 acres actually increased, while those below or above those limits decreased or remained static. Two thirds of all farm holdings are between 15 and 100 acres. With that stabilisation among the small-to-medium-acreage farmers, the IFA and, after it, the new Irish Farmers' Union (whose chief executive will probably be the present secretary of the ICMSA, Donal Murphy) cannot afford not to represent the less prosperous farmer.

Between 1965 and 1975, the number of holdings between 50 and 100 acres actually increased, while those below or above those limits decreased or remained static. Two thirds of all farm holdings are between 15 and 100 acres. With that stabilisation among the small-to-medium-acreage farmers, the IFA and, after it, the new Irish Farmers' Union (whose chief executive will probably be the present secretary of the ICMSA, Donal Murphy) cannot afford not to represent the less prosperous farmer.

Pat Dunne has just bought himself an Opel Senator. T.J. Maher insisted that his going-away present from the NFA should be a left-hand-drive diesel Mercedes. Their lifestyles are very different from those of the vast majority of farmers. But however far apart their approaches to farmer politics may be, they both depend largely on the farmers with smaller holdings - and smaller cars for their support. it is not for nothing that Joe Rea has been to Ballycroy, Co. Mayo, twice in the last two years.