How Ireland’s recovery strategy violates international law

Ireland’s government has not been shy about proclaiming its commitment to human rights. “We will require all public bodies to take due note of equality and human rights in carrying out their functions”, declared the Programme for Government published by Fine Gael and Labour last year. A few months later, in October, the government told the United Nations Human Rights Council that there was “no room for moral relativism or selectivity” in this regard, and that “respect for dignity and human rights” was “the incontestable baseline of decent politics everywhere”.

These are laudable words, but such annunciations have little meaning if they are not reflected in the design and implementation of social and economic policy. All too often, such affirmations belie policy programmes that take little account of the actual requirements of human rights law. Moreover, the context of an economic crisis makes it all the more important that proper protection be afforded to basic human rights, as it is precisely in such a situation that vulnerable groups are most exposed to violations. The question, then, is whether the Irish Government’s actions are in step with its rhetorical commitment to human rights. An analysis of the recovery measures deployed since the financial crisis took hold suggests they are not.

In October 1974, Ireland ratified the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), and in so doing took on an obligation to dedicate the “maximum of available resources” to protecting the economic and social rights of people living within its borders. International law states that these rights, which include the right to employment, housing, health, education and an adequate standard of living, must be realised progressively and without any unnecessary backsliding, or “retrogression”. Needless to say, the country’s protracted economic crisis has taken a heavy toll on these rights, with poverty levels rising fast, just as the queues at unemployment offices grow and thousands of families find themselves unable to make payments on unsustainable mortgages.

Contrary to the arguments of those pushing for deeper austerity, there do exist practical alternatives to the current approach of drastically prioritising spending cuts over tax increases. The principle of deploying “maximum available resources”, as set out by the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), requires that governments consider not only spending but also the generation of revenue through both the tax regime and other sources. Measures that could lead to retrogression, such as cuts in social protection, can only be enacted “after the most careful consideration of all alternatives”. This means that, where alternative options such as tax reform have not been fully considered, policies leading to deterioration in socio-economic outcomes represent violations of the Covenant. It would require quite a stretch of reasoning to argue that such alternatives were properly debated as Ireland’s recovery strategy was hurriedly designed and implemented from behind closed doors.

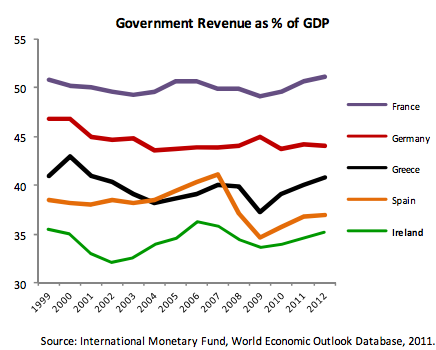

Ireland remains one of the lowest-tax economies in Europe, and arguments that a return to economic health is contingent on maintaining such a dramatically low tax take have been convincingly refuted. At the very least, a modest shift towards more progressive revenue generation could do a great deal to protect economic and social rights and confront deepening inequality, while also maintaining the competitiveness of the Irish economy. Moreover, now that retrogression has become clearly evident in socio-economic outcomes, the Irish government is obliged to take corrective steps immediately.

Ireland remains one of the lowest-tax economies in Europe, and arguments that a return to economic health is contingent on maintaining such a dramatically low tax take have been convincingly refuted. At the very least, a modest shift towards more progressive revenue generation could do a great deal to protect economic and social rights and confront deepening inequality, while also maintaining the competitiveness of the Irish economy. Moreover, now that retrogression has become clearly evident in socio-economic outcomes, the Irish government is obliged to take corrective steps immediately.

It has been argued in Irish courts that under the country’s dualist legal system conventions including ICESCR are not enforceable at the domestic level. This issue does nothing to diminish Ireland’s obligations as a party to the treaty, however, and the Irish government has repeatedly voiced its intention to give greater effect to such agreements in the domestic legal order.

Moreover, it is not only international legal obligations that impel the Irish government to properly consider the human rights of ordinary people before implementing measures that might impact their socio-economic wellbeing. The “directive principles of social policy” set out in the country’s Constitution require the Oireachtas to secure the right to an adequate means of living and “safeguard with especial care the economic interests of the weaker sections of the community”. These fundamental principles cannot be brushed aside when the Government finds itself facing fiscal difficulties, but that is exactly what the previous Fianna Fáil government did the moment it realised its mismanagement of the economy had set the stage for a crisis. Rather than adhering to the standards and norms set out in both the country’s foundational legal document, and the body of international human rights law to which it is party, it moved to impose the costs of its policies on ordinary families least able to pay. The main pillars of their ill-conceived recovery strategy are now being continued by Fine Gael and Labour.

The Center for Economic and Social Rights (CESR), a human rights think-tank based in New York and Madrid, has been tracking the impacts of the global economic crisis in various countries. A new CESR report - entitled Mauled by the Celtic Tiger: Human rights in Ireland’s economic meltdown - finds that the Fianna Fáil government at the helm of the country during both the boom and the onset of the crisis failed to properly consider its human rights obligations in the design and implementation of social and economic policies. The recently elected Fine Gael and Labour administration has signaled a greater openness to human rights norms, but the effective mainstreaming of these principles into the policy cycle remains little more than a vague promise.

CESR’s analysis also highlights the obligations of other actors, such as the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund, which likewise appear to have disregarded their human rights obligations in their “rescue” package. Those states that have ratified ICESCR are required to engage in international cooperation and assistance in order to protect and promote economic and social rights. Countries that are home to Ireland’s creditor institutions, or which count themselves among her creditors, must therefore see to it that their debt agreements do not impede economic and social rights provisions in the country. Moreover, they are required to ensure any influence they might hold over domestic policies works to support rather than undermine these rights. Given the obvious sway countries such as Germany, France and Britain have in the ECB and the IMF, and the role these institutions have played in pushing Ireland into the austerity trap, it can be argued that they have likewise been derelict in their duty.

Ultimately it is up to the Irish government to champion the socio-economic wellbeing of ordinary people in the country, however. Its failure to place human rights at the heart of the recovery strategy represents more than a moral and political failure – it is a transgression of its obligations under both national and international law. This situation is all the more troubling given the country’s repeated declarations of its commitment to upholding human rights. Such lack of coherence is further evidenced by the administration’s recent decision to seek a place on the United Nations Human Rights Council, and with it a boost in its international standing. Indeed, it would seem reasonable to suggest Ireland should redouble its efforts to secure the human rights of people within its own borders before settling into a new role monitoring the performance of other countries in this regard. A solid and much-needed first step would be to design and implement a revised recovery strategy placing human rights at its centre. {jathumbnailoff}

Luke Holland is a Researcher at the Centre for Economic and Social Rights (CESR). Prior to joining CESR, he worked as a journalist in The Irish Times and ITN, the producer of Channel 4 News and the ITV News at 10.

Image top: (UN Human Rights Council, 15th session) United Nations Information Service - Geneva.