How Charlie Won the War: The Battle for the Leadership of Fianna Fail

Back in 1979, before he bacame Taoiseach, Charlie Haughey was talking to a reporter about the infamous fingerprint scandal arising out of the murder of the British ambassador in July 1976. Haughey remarked that the central point of the scandal had been entirely missed by the press.

He invited the reporter to guess the identity of the person whose fingermark was left on a helmet found at the scene of the explosion. When the reporter fell for the bait and enquired whose it was, Haughey replied: George Colley's.

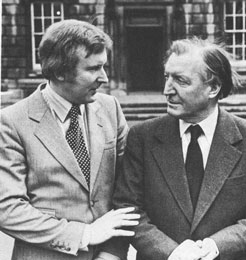

It was, of course, an entirely jockose comment but it did reveal the depth of antagonism that existed between the two men, an antagonism which has persisted since the early 1960s and which has yet to be resolved. The recent traumas within Fianna Fail have had more to do with the antagonism between Charles Haughey and George Colley, than with anything immediately substantive. However, the apparent pettiness of the clash does belie deeper conflicts within the party, which are never properly articulated, at least not by the protagonists themselves.

It was, of course, an entirely jockose comment but it did reveal the depth of antagonism that existed between the two men, an antagonism which has persisted since the early 1960s and which has yet to be resolved. The recent traumas within Fianna Fail have had more to do with the antagonism between Charles Haughey and George Colley, than with anything immediately substantive. However, the apparent pettiness of the clash does belie deeper conflicts within the party, which are never properly articulated, at least not by the protagonists themselves.

Fianna Fail has been in a state of acute schizophrenia since the beginning of the 1960s. It has been in this state since Eamon de Valera resigned the leadership. However, the roots of the party's distress go back beyond that point to the abandonment of any real radicalism either in economic or nationalistic terms in the late 1930s. The party was born out of a radical and revolutionary background. Its aspirations to the republican ideal and to popularist economic and social philosophy were, however, abandoned on its coming into office in 1932. Republicanism was uprooted within the party by the early 1940s. this time de Valera's Government was hanging former comrades in the IRA and allowing hunger strikers to die in appalling prison conditions. Lemass built up protectionist walls within which native Irish capitalism thrived - it wasn't socialism but, at the time, it was radical.

The extraordinary personality and appeal of de Valera masked the contradictions at the heart of the Fianna Fail party for so long as he remained leader. But on his departure the impatient Lemass discarded the pretences and exposed the confusions. Lemass abandoned protectionism and moved towards EEC entry. He gave de facto recognition to the Northern state in a manner which was more forthright than anything which had previously been done,

There were many within Fianna Fail at the time who were unhappy with the new direction of the party, though dissent then concentrated on the brashness of the mohair-suited young bloods whom Lemass had promoted within the party as the architects of the new Ireland. It is in the light of that background and it is in the Iight of the underlying contradiction between Fianna Fail's revolutionary republican past and its pragmatic conservative compromising incarnation against which all the antagonisms and conflicts within the party since then must be viewed,

Fianna Fail is not traumatised because of unique personality conflicts which find their origin solely in the extraordinary personal ambitions of Charles Haughey and George Colley. It is rather that the deep ideological confusion which afflicts the party exacerbates tensions which would be there anyway and which otherwise would be regarded as quite normal and containable.

The antagonism between Haughey and Colley began around 1962 over constituency fiefdom. Colley had supported Haughey's efforts to get elected in the 1950s and there was no sense of bitterness between the two arising out of Haughey's taking of Colley's father's seat in the 1957 general election. But when the two found themselves together in the Dublin North East constituency after the 1961 election the rivalry between them began. They staged what amounted to a "macho" contest in the 1965 election but Haughey won out handsomely by 12,415 votes to 5,745. Thereafter they were to represent separate constituencies but the damage had been done.

Colley identified early on with the older wing of the party, represented by Frank Aiken, Sean MacEntee, Paddy Smith etc., whom he had connections with through his father, Harry. Colley was also somewhat of a "gaelgeoir" at the time and thus was seen to represent the Irish or nationalist (republican was not then a term much used within the party) element of the organisation. In contrast, Haughey was seen as the representative of the new capitalist breed whom Lemass had fostered - a breed impatient with the old values and interested in modernisation, free trade and above all, the quick buck.

Once the 1966 leadership election was over Haughey seemed stronger than Colley within the party. From the Department of Finance he effectively ran the show and he began to repair his image with the republican wing by sponsoring madcap initiatives in Northern Ireland - it was one of these which led to the Arms Trial and his ostracisation from the party's higher echelons for five years. Colley was the main beneficiary of Haughey's fall. The antagonism found further fuel but by then their respective roles had changed - Haughey was now the republican hero within the party, Colley was the compromiser.

The circumstances of the Fianna Fail leadership battle in 1979 permitted Haughey to represent himself both as the republican and the manager supreme of the economy. Having won such a resounding victory in 1977 the party was in tatters following the debacle of the local and Euro-elections of June 1979 and the reverses of the Cork by-elections of November of that year. The manifesto of 1977, with which Colley was closely identified, had by then collapsed around the shoulders of the Lynch Government. But in spite of all that Haughey won the contest by a mere six votes. Colley, in his Baldoyle speech just 12 days after Haughey was elected, signalled that the battle would continue. And so it has.

The circumstances of the Fianna Fail leadership battle in 1979 permitted Haughey to represent himself both as the republican and the manager supreme of the economy. Having won such a resounding victory in 1977 the party was in tatters following the debacle of the local and Euro-elections of June 1979 and the reverses of the Cork by-elections of November of that year. The manifesto of 1977, with which Colley was closely identified, had by then collapsed around the shoulders of the Lynch Government. But in spite of all that Haughey won the contest by a mere six votes. Colley, in his Baldoyle speech just 12 days after Haughey was elected, signalled that the battle would continue. And so it has.

Haughey's term of office as Taoiseach proved an immense disappointment, even to his closest colleagues. He lacked the decisiveness and the determination which were believed to be his hallmarks. Also, his record on the national question proved disappointing. The litany of his failures as Taoiseach and as leader of the Opposition are well known, especially to readers of Magill. They are, however, worth repeating at this stage:

* his identification of the economic problems in his TV address of January 1980 but his subsequent failure to take action - as represented especially in his capitulation to the public service unions in 1980 - there was a 34% increase in the cost of public service pay in that year.

* his fiddling of the books in the January 1981 budget and his subsequent abandonment of all restraint on public expenditure in the run-up to the June 1981 election. (The cost of that exercise is represented in literally thousands of

job losses since then, caused by the corrective measures needed to repair the damage he did.)

* his gross exaggeration of the progress made in the Anglo-Irish talks of December 1980, which resulted in his being immobilised in the face of the H-Block crisis which commenced in March 1981 and which eventually cost him the June 1981 election.

* his opportunism as leader of the Opposition in opposing the July 1981 budget and the other measures taken to remedy the situation he caused while in office and his procrastination in appointing a frontbench.

* his continued opportunism in the February 1982 campaign and his sponsorship of the "magic budget" proposals, in conjunction with Martin O'Donoghue, proposals which were to greatly worsen the budgetary position in 1983.

While that record was sustained initially on being returned to office in March 1982, there was a dramatic change of tack following the Dublin West by-election and whether because of him or in spite of him, his Government began, at last, to show resolution in dealing with the economic situation. There is no reason to justify the two coups against Haughey in 1982. His record in Government and in Opposition by March 1982 had provided sufficient cause for his displacement but that was at no stage advanced as the reason for getting rid of him. It could not have been - because all the main protagonists, including George Colley and Des O'Malley had been members of his Government from December 1979 to June 1981 and had thus been party to the economic "crimes" perpetrated by Haughey during that time.

Equally, they shared his opportunism in Opposition and another opponent, Martin O'Donoghue, had sponsored with him the "magic budget" proposals immediately before the February election. By October there was a good deal less reason to oppose Haughey because his Government had at last begun to deal with the economic problems, an incongruity acknowledged by his opponents then. At no stage through all these traumas within the party have Haughey's major misdemeanours been even alluded to - e.g. the fiddling of the January 1981 budget, the abandonment of all restraint on public expenditure etc.

The reasons that the dissidents want to get rid of Haughey are a mixture of the following:

* they believe he is an electoral liability .

* they believe that he is divisive within the party and will never be able to unify it.

* the old antagonism.

The first is sustained only by the opinion polls. The general election results suggest that Fianna Fail could hardly have fared any better under any other leader, given the circumstances of the election and the prevailing economic climate. The second is self-fulfilling, and the third is there in secula seculorum. None of these provides any compelling reasons for persisting with this Haughey-must-go campaign, while other very compelling reasons go entirely unheeded.

There were good reasons for the most recent attempt to depose Haughey - the bugging of the telephones of the two journalists and the taping of a private conversation by Ray McSharry. But no evidence has been presented that Haughey himself was aware of what was going on; the doctrine of collective responsibility took a knock during the 1970 Arms Crisis, one from which it has never recovered.

The most recent putsch against Haughey began with the disclosures that Sean Doherty, Haughey's very personal choice as Minister for Justice, was involved in the instigation of the telephone tapping of Bruce Arnold and Geraldine Kennedy. There was also the additional revelation that Ray McSharry taped a conversation with Martin O'Donoghue with a tape recorder provided by the Gardai which was later transcribed by the Gardai.

The most recent putsch against Haughey began with the disclosures that Sean Doherty, Haughey's very personal choice as Minister for Justice, was involved in the instigation of the telephone tapping of Bruce Arnold and Geraldine Kennedy. There was also the additional revelation that Ray McSharry taped a conversation with Martin O'Donoghue with a tape recorder provided by the Gardai which was later transcribed by the Gardai.

The revelations about Doherty were especially damaging in the light of other revelations about his conduct as Minister for Justice - the attempted interference with the Gardai on late night drinking charges and drunken driving, the attempted transfer of a Garda Sergeant, the Dowra case, and the suspicious circumstances of the crash in Ballyduff, Co. Kerry involving the Minister's escort car.

Doherty wasn't just any other Minister. He was appointed to Justice by Haughey almost as an act of defiance against George Colley who had insisted in December 1979 on having a veto over the appointments to Justice and Defence. Thus Haughey was all the more vulnerable when his personal appointee proved such a liability. All the more so when Haughey failed to take any action against Doherty at the time of these revelations. even after the confirmation by the Government of Doherty's role in the phone tapping.

Haughey's position was further weakened by the suspicion that he himself had known and had probably asked for the taps - a suspicion bolstered by the revelation that he had attempted otherwise to curtail Geraldine Kennedy's reporting. The revelations about Ray McSharry were damaging. Firstly, they suggested that the taint of corruption extended far beyond one individual minister. Second. they implicated Haughey's most effective ally within the party and therefore undermined his effectiveness. The meeting on Sunday, January 23 was acrimonious but didn't impugn Haughey's leadership. Doherty came out badly in that he failed to explain convincingly his reason for the taps and in that he had managed to worsen his position by a piece of press manipulation the previous day. McSharry frightened the meeting with his account of the conversation with O'Donoghue the previous October.

It was only over the following few days that the full significance of the affair and particularly that of the conversation between McSharry and O'Donoghue became apparent to TDs. There was an appreciation that something was very wrong about the party which could not be put right without radical change - a change involving the leadership itself. The belief, however, that Haughey himself had decided to resign, following representations from several former allies on the following Tuesday appears now entirely mistaken. A critical meeting was held in Haughey's office on Tuesday night (January 25) and again the following morning. These two meetings were attended by Ray McSharry, Padraigh Flynn and Brian Lenihan. It was there that decisions were taken on how to handle the new crisis.

Lenihan was the primary tactician at that stage and there was a certain irony about that. He and Haughey had been close allies in the 1960s and it was Lenihan who did most of the leg-work for Haughey in the 1966 leadership battle. But Lenihan failed to support Haughey in the 1970 Arms Crisis and there had been a coolness between the two from then onwards.

In the December 1979 leadership contest Haughey anticipated that Lenihan would campaign vigorously for him but in the event Lenihan spent almost the entire duration of the campaign in the bar in Buswells Hotel, across the road from Leinster House, in the company of Ray Burke. Both Burke and Lenihan then voted for Colley, although Haughey was to believe for some time afterwards that Lenihan had voted for him.

Immediately after his election as leader in December 1979 Haughey invited Lenihan to come into his office. Lenihan was still suffering from the rigours of his days in Buswells and was unable to offer much help at the time. He did mutter, prophetically as it turned out, "Healing, Charlie, healing" which Haughey eventually understood to be an injunction to unify the party. In contemplating the formation of his first cabinet, Haughey thought of leaving Lenihan out altogether but when Colley and O'Malley refused Foreign Affairs and O'Kennedy had moved to finance, he was slotted in.

When the front bench was eventually reshuffled in lanuary 1980 Lenihan was again almost left out entirely and was eventually given a policy function, one to which be was uniquely unsuited. He did nothing to help Haughey in the attempted coup of March 1982. Neither did he help Haughey in October. This time around he proved Haughey's most crucial ally.

McSharry, in spite of his departure from the frontbench, was also a major figure, primarily in steadying Haughey's nerve and steeling his determination to persist. Flynn offered enthusiasm and energy. Others who were of critical assistance included Frank Wall, the party general secretary, who was able to keep tabs on the organisation as a whole, and Haughey's old ally, P.J. Mara, whose own involvement in the recent embroglio was hampered by his unsuccessful candidacy in the Senate election.

McSharry, in spite of his departure from the frontbench, was also a major figure, primarily in steadying Haughey's nerve and steeling his determination to persist. Flynn offered enthusiasm and energy. Others who were of critical assistance included Frank Wall, the party general secretary, who was able to keep tabs on the organisation as a whole, and Haughey's old ally, P.J. Mara, whose own involvement in the recent embroglio was hampered by his unsuccessful candidacy in the Senate election.

The statement to the parliamentary Party meeting on January 26 that he would go in his own time and would consult his Parliamentary colleagues was interpreted as an indication that he would go by the following weekend. However, Haughey had already decided to hang on and fight it out if necessary - the holding statement proved a vitally important strategem. When he didn't go by the weekend the expectation was that he would be removed at the Parliamentary Party meeting on the following Wednesday (February 2). The likelihood is that he would have been voted out then. The feeling within the party was intense. There was also the point that Haughey would not then have had the Tunney report to exonerate him from blame in the bugging scandals something which was to prove vital at the end of the day.

However ghoulish it may be to suggest, it remains a fact that Clem Coughlan's tragic death on Tuesday, February I saved Haughey from defeat. Coughlan himself had decided to vote against Haughey but that was not the issue. The postponement of the decision by a further five days proved critical. By then the panic which was engendered by the bugging revelations had abated somewhat and the Tunney report had become available. Haughey himself almost blew it with his provocative statement of Thursday, February 3, when he said he was going to stay on in the interests of the party. He managed to correct this in his radio interview of Sunday.

The line up of Haughey's opponents was very much more formidable this time than ever previously, primarily because of the defection of formerly close allies, notably Ray Burke. He simply had concluded personally that Haughey's position was untenable. Ben Briscoe's alignment with the anti-Haughey faction wasn't quite the blow to the Haughey side that the media represented. Briscoe had voted for Colley in 1979, although he tried to give the impression otherwise after the vote. He and Haughey had never been close and the "I love you" reciprocation at the meeting on Sunday January 23 was, at least on Haughey's part, a piece of charade and was intended to be seen as such but, apparently, was not.

The line up of Haughey's opponents was very much more formidable this time than ever previously, primarily because of the defection of formerly close allies, notably Ray Burke. He simply had concluded personally that Haughey's position was untenable. Ben Briscoe's alignment with the anti-Haughey faction wasn't quite the blow to the Haughey side that the media represented. Briscoe had voted for Colley in 1979, although he tried to give the impression otherwise after the vote. He and Haughey had never been close and the "I love you" reciprocation at the meeting on Sunday January 23 was, at least on Haughey's part, a piece of charade and was intended to be seen as such but, apparently, was not.

The nomination of Briscoe as the person to front the recent putsch against Haughey was, from the point of view of the dissidents, unfortunate. Briscoe has little prestige or credibility within the Parliamentary Party and his closing speech on his own motion was a disaster. The dissidents, in fact, were so badly organised that they didn't even have a seconder lined up for the Briscoe motion. Charlie McCreevy had to step in to do the needful.

That crucial meeting on Monday, February 7, was determined by the agreed agenda - it could hardly have been better suited to Haughey. The protracted discussion on the Tunney Report and particularly the concentration on the money offered by O'Donoghue to "de-compromise" McSharry or anybody else who might be compromised, deflected attention from Haughey. Then the announcement of the removal of the whip from Doherty also defused the situation considerably.

By the time the leadership issue came to be discussed the meeting was weary and then one of the contenders for the leadershlp, Gerry Collins, appears to have made a critical error. Instead of pushing for Haughey"s resignation by a measured onslaught on the leader, thereby showing the collapse of the middle ground for Haughey, Collins played it soft. He did so apparently because he felt sure that Haughey was going to be defeated anyway and he didn't want to appear to have been the one to push him - it would have damaged his compromise candidacy.

Another factor favouring Haughey was the absence of any clear-cut and credible alternative leader who would stand a good chance of uniting the party. It seems that Gerry Collins was the favourite to succeed had Haughey been deposed but only two years ago Collins's stock within the party was very low - Haughey would have kept him out of the cabinet in December 1979 had it not been for George Colley's intervention.

While even George Colley was quoted as saying that the leadership issue was now settled at least until after the next election, it is very unlikely that the turmoil within Fianna Fail will abate for long. Haughey has little chance of uniting the party, even if he genuinely wanted to. He is so crisis-prone that another major trauma is certain to break out before long and then there are very many more revelations to come.

Very many more.