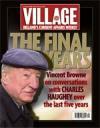

Haughey: The Final Years

Charlie Haughey's last five years were a steady and sad progression towards death. During that time, Vincent Browne visited him frequently at his home in Kinsealy. Here he writes about those visits and those conversations

He was melancholic in the last few months. I asked him eight weeks ago was there anything in his career in which he took pride. He said, "No, nothing." On another occasion I said, "You have had a good life." He replied: "Look at me now."

His condition got worse and worse over the years and every now and again I was shocked by his emaciation and shocked again a few months later by further emaciation. Certainly from a year ago almost every time I went to see him I thought on leaving I would never see him again. On one occasion I thought he was thinking that too. That day he saw me out to the front door – I think it was the last time he did that. And as I was about to leave he said: "Give me a hug." We hugged. I left in tears and couldn't look back to see how he was. When I drove around the roundabout outside his front door he was still in the doorway waving, which had never happened before.

He said a few years ago he believed he would never die but the imminence of death bore in on him in the last few months. He didn't talk to me about it, outside oblique references, but at times, in talking about his ailments, he would break down momentarily. The cancer had got into his bones he said over a year ago. More recently he said it had spread further, into his liver, his kidneys and beyond.

He was getting blood transfusions and was going into the Mater Private every few weeks. He got a great boost from these and would be in fine fettle for a few days afterwards, then sinking back into listlessness and despondency.

We became friends over those five years. We talked about everything: politics, tribunals, personal stuff, family, history, money, the Greeks, the Romans, Alexander the Great, wines, nature and people we knew in common – PJ Mara (of course), Paul Kavanagh (the former Fianna Fáil fundraiser), Dermot Desmond, Albert Reynolds, Bertie, Oliver Barry, Gerry Collins, Seamus Brennan, Mary Harney, Bertie, Michael McDowell, Padraig Flynn, Enda Kenny, Bertie, Garret FitzGerald, Tim Pat Coogan, Michael Mills, Bertie, Martin O'Donoghue, barristers, judges, Miriam O'Callaghan, solicitors, Gillian Bowler, Bertie, Maire Geoghan-Quinn and Bertie.

There was no subject off-limits and he put up, stoically, with abuse, ridicule and wind-ups. After a while he got attuned to the wind-ups and would pay no attention – he would simply go on with what he was saying.

But there was one wind-up which worked every time for a while. I invented a story of a liaison between him and a well-known woman journalist. There was absolutely no foundation to this at all but I used to bring it up casually and always he got irritated. Once, explosively so. Pointing towards me with the index and small fingers of both hands, he said through gritted teeth: "I tell you once and for all that is totally untrue." I said something to the effect, "But you lie to me about everything else, how can I believe you on this?" He had the good grace to laugh after a moment's hesitation, during which time he probably considered homicide. Afterwards the wind-up never worked. Disappointing.

He had got a beautiful black collie dog at one stage and was rapturous about him. He talked about cutting the hay in the field at the back of the house – it was done for the grandchildren. He spoke a lot about his visits to France which he loved and found hugely therapeutic. He had to return suddenly from a visit there two summers ago because of a deterioration in his medical condition. I don't think he ever returned.

We spoke of the monies he received from various people. He had seen nothing wrong with it. Winston Churchill was bankrolled by wealthy aristocrats throughout his career and nobody thought any the worse of him on that account.

Maureen Haughey used to join the conversations from time to time. I used to try to draw her out about her father, Sean Lemass, and both she and Charlie would talk animatedly about him. Lemass's wife used to bring him breakfast in bed every morning at 8.30am and bring up the post and papers sent out from the Department of the Taoiseach. Lemass would read the post and the official papers and by 9.30am he would have taken all the decisions he needed to take for the day. Then into the Department for 10am. Home for lunch at 1pm and at 5pm he would stand up in his office, put on his overcoat, indicating to whoever was there he was about to depart. Then home, where he would read history or biography books and think.

Maureen Haughey used to join the conversations from time to time. I used to try to draw her out about her father, Sean Lemass, and both she and Charlie would talk animatedly about him. Lemass's wife used to bring him breakfast in bed every morning at 8.30am and bring up the post and papers sent out from the Department of the Taoiseach. Lemass would read the post and the official papers and by 9.30am he would have taken all the decisions he needed to take for the day. Then into the Department for 10am. Home for lunch at 1pm and at 5pm he would stand up in his office, put on his overcoat, indicating to whoever was there he was about to depart. Then home, where he would read history or biography books and think.

Charlie clearly loved Sean Lemass, as of course did/does Maureen. She used to correct him on his recollections, gently but firmly, and she was usually right. She had/has a great insight into his political life. They got on effortlessly, he teasing her often, she smiling in happy resignation.

He – they – loved gossip. He would perk up delightedly with news of scandal and reciprocate with jaw-dropping revelations. Some concerning people still very prominent in public life. I mentioned one time that a mutual male friend was seeing a particular woman. "She's no oil painting," Charlie said. I went into helpless laughter. "You are not much of an oil painting yourself," I said to the emaciated, desiccated figure in front of me. He saw the humour and laughed too.

He called me out two years ago to tell me he had decided to write his autobiography – his family had persuaded him to do that. He wanted to know would I assist him. I said I would "assist" but the work would have to be his, not mine. He asked me to find a researcher for the project, which I did: Colin Murphy, now a journalist with Village. Colin and I went out to Kinsealy one Monday morning shortly afterwards. There had been a prominent piece in the Sunday Times the day before about his private life and he had decided not to proceed with the autobiography. But Colin did some research work for him subsequently. I think he had talked to several others about this project, including Anthony Cronin and Martin Mansergh.

Several efforts were made to get him to do television interviews about his life. Noel Pearson and Cathal O'Shannon went out several times and thought they had got him to agree to be interviewed, but he backed off. It was never on. He would be drawing more trouble on himself by anything he said or didn't say. Miriam O'Callaghan tried to persuade him over several months to take part in the TV series. She probably had the best chance of persuading him, but to no avail.

He was contemptuous of the "demands" of "history", of the contention he "owed it to history". Others say he was obsessive about his "place" in history, he conveyed to me he couldn't care less.

I went out to see him around the beginning of June last year. He had been very unwell around that time and there were reports in the papers that his death was imminent. There was a garda at the gate. I asked the garda why a garda presence. He said because of the state of "your man" hordes of sightseers were coming around and they had to be stopped going up to the house.

Usually we were alone, aside from Maureen. But on a visit on 4 December 2004 (a Saturday) there were several people there. Seamus Collimore (a former Fianna Fáil TD for Wexford and a very close friend of Charlie), Des Peelo (Charlie's personal financial adviser), Frank Ward (former general secretary of Fianna Fáil), a few neighbours and Charlie's two son's Conor and Seán (perhaps I am wrong abut Conor Then again on a Christmas visit, on Friday 23 December last there were some neighbours in, his daughter Eimear was there and then his daughter-in-law, Jackie, arrived with carol-singers from Malahide. We all went out to the hall to listen to the Christmas carols. Charlie looked awful and bored. But then was animated talking to the singers. Jackie, a spectacularly beautiful woman, had her arms around him kissing him in the head. Photos were taken, the singers departed and we went back to the bar.

Again what was striking was Charlie's ease with his family members. The obvious affection there was for Jackie, the obvious bond with Eimear, his ease with his sons.

Often I thought how privileged I was to have such access to perhaps the most interesting personality of Irish history in a century or more – maybe Michael Collins or Eamon de Valera would take precedence but he is/was in that league. And over the years I got very fond of him. I had always liked him, even when we were in adversarial combat while he was Taoiseach, but now there was a fondness. I got fond of Maureen too but that fondness wasn't returned and for good reason.

I recall a lunch we had in the Berkeley Court hotel just before or just after he became Taoiseach in December 1979. I arrived a little late and he had his head in his hands. I apologised for being late. He didn't respond. I apologised again, no response. I said: "Jaaze, I was only six minutes late, no need for a sulk." No response. After a few minutes I said: "If you are not going to talk to me I am going to leave because there are people looking over at this table and they are thinking we are having a homosexual tiff." That did it.

Because of his fascination with Greek, Persian and Roman history, at one stage in 2002, I think, I suggested we would both go to Hellespont, otherwise known as the Dardanelles in Turkey. It was here where the Persian king Xerxes built two bridges by tying boats together to allow his huge army from Asia to Europe, threatening Greece. Alexander the Great used the same trick when leading his army into Asia three centuries later. He was intrigued but felt he could not be so far away from his medical attendants. According to the journalist James Morrissey, he told Morrissey I had proposed we go to the "Holy Land" and he had opted out because he couldn't bear to be with me for ten days!

The last time I saw him was on Monday 8 May, just six weeks before he died. I went out to Malahide by Dart and got a taxi to Abbeville. For once I was on time and he noted it. He was standing at the entrance to his study just up the stone steps in the imposing hallway. He didn't look much different to how I had found him on my previous visit on Holy Thursday, 13 April, but he did look awful. A tiny skeletal stooped old man, shuffling in his slippers down the narrow corridor, then through the sitting-room to the bar at the back of the house. He collapsed on a wicker chair and I went behind the bar and got a bottle of white wine from the fridge. I asked him what the wine was and he told me – I thought I would remember but don't. I opened the bottle, got glasses and poured the wine for us both.

I had thought on my previous visit on Holy Thursday that definitely I would never see him again. I would not have been surprised had he died that night. But on 8 May he seemed, initially, in better form. He had just come back from hospital where he had had another transfusion and said this had picked him up quite a bit. He had a chair-lift installed in the house which enabled him to get up stairs. He didn't say it but it must have been a great relief for Maureen who was left to look after him every evening when the visitors had left. He wouldn't have a nurse stay in the house and she must have been hugely stressed. And irritated by visitors who drank with Charlie for hours and then left her to deal with the consequences. On my previous visit I got the impression she was not too pleased.

But on 8 May he talked about Joe Moran who was buying the property from him. He said Joe was a fine fellow had told him (Charlie) he could stay at Abbeville for as long as he wanted.

For the first time in all the visits since April 2001 I thought he had slowed down mentally. But we talked about Albert Reynolds and then about Gerry Collins, which led to a discussion about hats (an explanation for the line of conversation would run the risk of libel). Maureen had come into the bar at that stage and she said hats were her family business. The Lemass family had a hat shop in Capel Street, near Capel Street bridge. She said an aunt was the last to own it and had wanted her (Maureen's) brother, Noel Lemass (who was later a TD), to run the shop. But he wasn't interested, so the shop was sold. Maureen was behind the bar when this exchange took place and Charlie couldn't hear what was going it. He was irritable.

He said he had read The Da Vinci Code and liked it but felt it had gone on too long. I was surprised he had risked a work of fiction, for his regular reading had been history and biography.

We talked of the joys of alcohol. He said he was never able to drink pints of Guinness. He just couldn't face the enormity of a pint. He liked the white wine we were drinking but usually, he said, he drank red wine. I think he was put off drinking red wine because of his medication.

I stayed for an hour-and-a-half and then a taxi arrived for me and I left. It was the least satisfactory of all my visits, partly because I had felt I had outstayed Maureen's welcome on my previous visit and I was keen to get away. Partly because I felt he was tired. But also because I felt he was better than he had been previously and I would see him again soon. We spoke on the phone afterwards and made tentative arrangements for me to go out two weeks before he died but that was cancelled because he had to go into hospital.

I arrived a half hour late for that Holy Thursday meeting. Again Charlie was standing at his study door. I was taken aback by how much more emaciated he was than he had appeared previously but it was only later on that I came to perceive the scale of his deterioration.

We walked through the sitting-room. The volume on the television was very loud and he reached to get the remote control. Very shakily he managed to turn down the volume. I told him that RTÉ was making a fortune from the video of last summer's TV series about him. He was vaguely amused, but only vaguely. We went into the bar and he asked me to go and get the wine from the fridge.

When I sat with him he looked even worse. His right eye was almost closed. His trousers had been falling off him as we had walked to the bar along the corridor, so emaciated was he. There were purple marks on his hands. I asked him what they were and he said they were blood clots. He said he had a tingling sensation down his right arm into his hand and this was often very painful. Morphine could keep most of the pain at bay but not the pain in his hand. He was very drowsy at times that day. The right eye closed and at times the left eye would close as well. He would drop off to sleep, then wake up and apologise. He said the medication was making him drowsy.

We talked about his condition. He said he had been very bad. He had gone into hospital the previous Monday week and was in a very bad way. He said that he was oblivious to a lot of what was going on and that he had two stomach bugs, this is the hospital bug that is going around. He said that he was very weak.

I asked him had he had pneumonia and he said he might have had but he didn't really know. At one stage we (again) were talking about drink, about the curative affect of alcohol. He said that he missed a drink in the evenings when he was in hospital and on one occasion he had asked the nurse, a lovely Pilipino nurse, if his doctor would sanction him having a drink. She smiled broadly and beatifically and said she could speak on behalf of his doctor and yes indeed he could have a drink.

He had said earlier on that his condition was very much up and down, that some days he was great and other days he was poorly. He had been great a few days previously but he seemed to indicate that he wasn't great that day, although he was keen to talk.

He said that he had lots of people coming out to see him. Too many people. I thought that maybe I was outstaying my welcome and at one stage, I said, "Would you like me to go?" and he said, "Oh no, no no."

The grounds were magnificent. Seas of daffodils along the laneway coming in from the road and again coming up the avenue to his house. Trees starting to bloom and the apple blossom coming out.

We talked a bit about Bertie. He said that Albert had wanted to come out to see him and he was being urged by several people, including Oliver Barry and others, to see Albert but that James Morrissey had advised him not to. He said that he thought that Albert would go to the papers afterwards and make a big deal of it.

I referred to Garret's visit and said that I felt that Garret had behaved well even though he had blundered into saying that he had been out to see him. Charlie said, "Oh yes, Garret behaved very well."

At one stage he said, "Lynch was the biggest shit of them all." I don't remember how that came up. We talked a bit about George Colley's father, Harry Colley, and his statement to the military history museum about his part in 1916 and the War of Independence. Charlie obviously liked Harry Colley (whose seat, incidentally, Charlie captured in the 1957 general election).

We talked about Sean Doherty and he said that he had been very upset by the media coverage at the time of Doherty's death and the insistence that Doherty had given him the transcripts of the telephone-tapping. Catherine Butler was able to authenticate that he never saw the tapes of the transcripts of the telephone-tapping.

We talked about PJ for a bit and he agreed that there was a lot to PJ, a lot of substance and he was a decent, loyal, honourable fellow. There was personal stuff about PJ, more personal stuff about Paul Kavanagh.

We talked about the vagaries of political events. He remarked how the Berlin Wall was built over an Easter weekend and had it been built at any other time there would have been protests around the world and they probably wouldn't have gone ahead and yet, because of the chance occurrence of it being built on the Easter weekend, it was there before the world could do anything about it.

I asked him how he had got to know about wines and he said that some fella, McLoughlin I think, that he knew in UCD, used to go down to a bar somewhere off Grafton Street (he couldn't remember the name of the bar) and they would sample wines during the afternoons and that's how he got into wines while he was a student.

I asked him how he got into horses and horse-riding and he said that there used to be circus horses in Belton Park when he was growing up and that he used to ride the horses bareback around Belton Park and I said I suppose the fact that they were circus horses meant that they were fairly domesticated and he said, "Oh yes, but often they would throw you off."

There was also reference to Clontarf Baths. He used to swim a lot down in Clontarf Baths and play water polo. He said he was no good at water polo and I think it was during this time that he met Pat O'Connor, who was very good at it. He said that they used to drink bottles of stout down at Clontarf Baths and this was great hilarity in their teens, he would have been 15, 16 or 17 at the time.

At another stage he said that playing football had given him more joy than anything else. He had said this on previous occasions and he said the sheer joy of being able to run with the ball from hand to toe had given him more pleasure than anything else. He was happiest, he said, at that stage of his life. That was in his late teens, when he was living at home in the modest house in Belton Park, Donneycarney, going to St Joseph's in Marino – all before politics, power, wealth, the lavish mansion and the lavish lifestyle.

We talked a bit about a judge of one of the superior courts whom Charlie knew well at one stage and to whom he had given preferment at the latter's insistence. He had reason to phone this person a few years ago and was fobbed off. As on several previous occasions, we talked about barristers. He became most heated about that species – he himself had been called to the Bar around 1947 but he had never practiced. Had he done so he would have made far more money than he ever earned, or even ever received, as a politician but the thought of being part of that "species" repulsed him. He had a particular animus for a particular barrister, whom he regularly referred to as "that fat fucker".

We talked about the bar that we were sitting in. He said that this was Sam Stephenson's or Arthur Gibney's idea and that they had bought the bar in Belfast, or all the contents of the bar in Belfast, and brought them down to Kinsealy (actually, according to Sam Stephenson, the bar itself came from a bank in Belfast and the wood panelling came from the old Jury's hotel in Dame Street, Dublin). Over the door there were the portraits of the 1916 leaders, a copy of the Proclamation. Over to the right a portrait of the south Dublin Ward Hunt.

We talked about his son Seán and Bertie's handling of the reshuffle last February and what a mess Bertie had made of it. He referred to Paddy Smith having resigned as Minister for Agriculture in 1964. Charlie said Smith had resigned on an evening and that Sean Lemass (the then Taoiseach) had reshuffled the cabinet by the following morning with Charlie as Minister for Agriculture and Brian Lenihan replacing him in Justice. My recollection had been that Smith phoned early one morning and resigned and by the time he had reached Dublin by car, Lemass had made the cabinet readjustments.

We drank a full two bottles of that magnificent white wine that day. At one stage he poured wine from his glass into mine but after he had spilt some of his own wine, when he again dozed off momentarily, he poured wine from my glass back into his. I protested he had taken more of my wine than he have given me a few minutes before. He replied with a familiar epithet.

I got up to leave and he came with me outside the bar. We stopped to look at photographs on a wall just by the bar door and while we were doing so he began to collapse. I took hold of him and was shocked by how light he was. I helped him back into the bar where he sat down for a minute or two. Maureen arrived and wanted him to go to a small room down the corridor for his dinner. I helped him down and left him seated at the table, with another television on, this one with Sky News.

I let myself out, this time certain I would never see him again. Desolate, lonely, devoid of any sense of achievement, bar one. An accomplishment he shared with Maureen: they brought up three sons and a daughter, who are secure, well-adjusted, happy, loving. Of course not happy in the immediate aftermath of his death, but happy generally in themselves. And their children, in turn, seem happy. This wasn't a corny observation. It came after he said there was nothing in his life of which he was proud.

Vincent Browne