Felipe Contepomi: Life at No.10

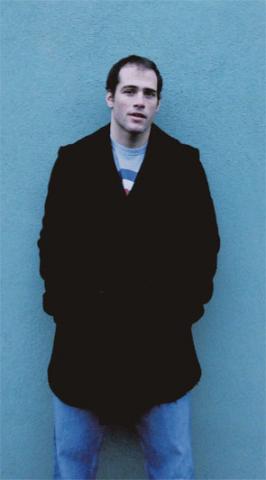

Pin-up, father, ambassador, medical student and razor-sharp fly-half, Felipe Contepomi still takes a backseat to his brothers in terms of fame. He tells Justine McCarthy about his family dynasty, his hopes for rugby back home in Argentina and Ireland's chances in the World Cup. Portrait by Eoin Moylan

In Cardenal Newman College, Buenos Aires, where three of the most illustrious alumni bear the surname Contepomi, there hangs the stock portrait, familiar to anyone educated by the Christian Brothers, of the religious order's Irish founder, Blessed Edmundo Rice, teaching pale, small children to read. The school's mission statement pledges it to promoting “an Argentinian society that lives the values of the gospel”, promulgating justice, peace and responsible freedom.

A little more than a decade after leaving Cardenal Newman College, the most famous Argentinian in Ireland sips coffee in a discreet corner of Leinster Rugby's side chapel, Kiely's pub in Donnybrook, on a shivering winter's night. The province's blue-and-yellow flags flap frostily on the pub's curved street front. Giant picture frames on the walls inside display Ireland and Leinster rugby jerseys signed by legends of the game and the handful of after-work patrons dotted around the bar-room are flaunting their allegiances in the colourways of their supporter shirts. Behind the bar, a poster advertises the latest addition to the bill of fare; a “Trevor Brennan Cocktail”.

“I would say it has a lot of spirit in it,” Felipe Contepomi smiles. Politely, but firmly, he declines to discuss the Dublin-native Toulouse lock's attack on an Ulster supporter during a Heineken Cup tie in January. Stressing that he is speaking generally, he says: “The beauty of rugby is that it is a contact sport but it is a noble sport. If you don't respect the rules, it will turn into a big ring with 15 boxers fighting 15 other boxers.”

He started playing the game at the age of eight, lining out in the back row for Cardenal Newman, where rugby was the main sport (it is largely a private-school pursuit in Argentina), alongside his “not-even-similar” twin brother, Manuel, a fellow international who recently left Bristol Rugby to play for an Italian club.

“He was the good one,” claims the older twin, by virtue of being delivered into the world after his sibling. “He started playing for the national team before me but he was unlucky with injuries. Everyone would have looked at my twin brother going all the way through.”

In a joint interview they gave in Buenos Aires five years ago, the Contepomi twins agreed that Manuel was the “rebellious” one and that Felipe was “calmer”. At the age of 29 (he will turn 30 next August), juggling a hectic lifestyle as a final-year medical student, the father of a one-year-old girl, and a pin-up favourite of both rugby purists and smitten females, Felipe's self-containment is his most abiding characteristic. He has been called “pure magic”, “the Latin virtuoso” the Pumas' “pretty boy” and Leinster's “puppet-master” but there is no hint of contrived modesty in his reply when asked if he was always brilliant at rugby. “I don't consider myself brilliant at rugby.”

Contepomi grew up in a sort of low-altitude, Español edition of the The Waltons, one of five boys and three girls born to the daughter of an Italian immigrant and a former Argentina rugby player (capped in 1964, before he went to England to pursue his studies and a job) and, later, Argentina's team manager. The family expanded by half as much again when the four children of a couple the Contepomis knew were orphaned by their parents' sudden deaths and came to live with them. A 20-year gap separates the eldest from the youngest of the children. Of the eight boys in the household, the most famous in their own country is Carlos José, also known as “Bebe” Contepomi, a broadcast rock journalist with his own television programme. When Bebe, who is celebrated as “La Voz del rock” in their homeland, visited Felipe at his Milltown home in Dublin's southern suburbs, it must have been a novel experience being the one overlooked by the public while his brother was the one being fêted. Or so one supposes. “He doesn't care if he is recognised or not,” says Felipe, stoking the burgeoning impression of a family bred on samba, sport and scouts-honour civic spirit.

Home for the Contepomi clan is Hurlingham, an exclusive Buenos Aires suburb given its name by the local cricket, polo and country club whose early membership boasted the Foxford, County Mayo native, William Brown, founder of Argentina's navy.

On their maternal genealogical merits, the twins', whose Italian surname was passed down through several generations on their father's side, would have qualified them to tog out for the Azzurri, thus permitting them to play in the Six Nations championship and rescuing them from Argentina's international fixtures doldrums.

“I wouldn't have played for Italy,” responds the top scorer in last season's Heineken Cup and Celtic League and the Bank of Scotland's senior Leinster Player of the Year. “I feel Argentinean. Obviously, I am Argentinean.” As if to prove the point, his slimline mobile phone purrs and he picks it up, apologising for the interruption. “Hola,” he says into the phone, plunging into a monologue more melodious than any Iglesias.

The opportunity to scrutinise him is irresistible. The jaw is male model-square. The hands that double-job with the oval ball and the scalpel are clean and groomed. The liquid earnestness in his brown eyes and the thinning hair at the front of his head combined with what he is wearing create the image of a serious, dutiful young man. He has come from accompanying “the professor” on his rounds in Beaumont Hospital, via the Argentine embassy to collect “papers that need to be sent off” and is dressed in a collision ensemble of workwear and sportsman's casuals: blue shirt, spotty knotted tie, cream canvass trousers and zip-up navy cardigan. He does not appear quite so flamboyant without the number 10 on his back.

As a nine-year-old in Buenos Aires in the summer of 1986, it was another number 10 that seduced him; the one worn by Diego Maradona while leading Argentina to its second World Cup title. Soccer – or, as Contepomi calls it, football – “is not a sport” in Argentina. “It is religion.” He has met Maradona several times, most recently when the recovering drug-addict superstar attended the last Pumas match in Buenos Aires. “He is my only sports idol. He is one of only a small number of players who have been so influential in a team sport. You can speak about Michael Jordan, but there are only five players on a basketball team.”

The collegiality of rugby is the cornerstone of the Leinster fly-half's passion for the sport and, yet, because he hails from a Cinderella rugby nation devoid of international club competition and doomed to playing inter-country friendlies in the limbo between World Cups, he is often excluded from that fraternity. While his Irish international teammates decamp from Leinster for the duration of the Six Nations, a world-class player like Contepomi, known to Irish bloggers as “Doctor Phil”, is left to captain the team through the second-string Celtic League.

“We would like to join the Tri Nations, the Six Nations, whatever, but there is a difficulty because there is interest from only one side,” he echoes the imprecation of his Los Pumas colleague, Agustín Pichot, following Argentina's victory over Wales last June. “There is a logistical problem and a business problem with Argentina getting into one of the tournaments. You see the results Argentina have been getting and everyone says they should be getting competition. There has been talk about joining the Tri Nations but that is not easy when all players are in the northern hemisphere. Hopefully, we'll be involved in international competition sooner rather than later,” he says, expressing a desire that is probably harboured by all his 100 compatriot rugby players exiled from home.

“Football is the main sport in Argentina. After football, there is basketball. Tennis players are popular because they have done well. Rugby would come in the second layer of sport. If the Pumas are playing, they will take 45,000 people in a stadium but, having said that, rugby is becoming popular at national level, but not at weekend level because a lot of players are abroad. If you give me the budget the IRFU has, I could do a lot more things with it in Argentina than they have done here. They have loads of clubs and loads of people playing rugby, probably more than Ireland, but it is still an amateur sport. You don't have revenue so it's very difficult, you know.

“There is no professional rugby in my country. The only thing that is professional – in inverted commas – is the national team, because most of the players are playing abroad.”

Contepomi's contract with Bristol was about to expire and he was planning to return home to Argentina when Leinster Rugby offered him the job, complete with a flexible arrangement for him to study medicine at the Royal College of Surgeons. He will sit his final exams in April and May with a view to becoming a full-time surgeon, possibly specialising in orthopaedics, where he has had some experience as a customer, having spent six weeks in a neck brace with a rugby injury. This is his fourth season with Leinster and he signed on for two more at the end of last year. After that, he will decide whether to remain for yet another season or to commence his internship in a hospital.

Contepomi's contract with Bristol was about to expire and he was planning to return home to Argentina when Leinster Rugby offered him the job, complete with a flexible arrangement for him to study medicine at the Royal College of Surgeons. He will sit his final exams in April and May with a view to becoming a full-time surgeon, possibly specialising in orthopaedics, where he has had some experience as a customer, having spent six weeks in a neck brace with a rugby injury. This is his fourth season with Leinster and he signed on for two more at the end of last year. After that, he will decide whether to remain for yet another season or to commence his internship in a hospital.

“It is difficult to plan from day to day,” he admits. “At the moment it's a bit insane. I think it is too much. These are the last few months I have to get my degree. I have a baby daughter and I would like to spend more time with my family. I don't think you can go on living like this forever. It is exciting and I don't regret anything I have done, but you have to put a stop to living like this some time.”

His day starts at 6.45am when he leaves the home he shares in Milltown with his partner, Paula, an Argentinean public relations executive, and their year-old daughter, Catarina, for Beaumont Hospital across the city. He travels back through town for rugby training in the middle of the day, then returns to Beaumont until the evening, when he goes for fitness training in a Clonskeagh gym. Considering his nerve-jangling schedule, Contepomi's disclosure – when asked – that he is not obliged by his Leinster Rugby contract to do media interviews such as this, indicates a sense of public duty redolent of the Christian Brothers' ethos in Buenos Aires.

Though he says he wishes neither to manage the Argentinian rugby team nor to enter national politics when he goes back home, he exhibits no reticence on either subject. He was, for instance, only five years old when his country went to war with Britain over the Malvinas/Falkland Islands in the south Atlantic, and yet he discourses passionately on the slaughter of his countrymen. (One thousand of them were said to be on board the Belgrano when it was torpedoed by Margaret Thatcher's navy in 1982.)

“It is part of our history,” he says. “I think it was a nonsense war. Even in Argentina we cannot understand how we were involved in that. To send young people, as they were – young boys – out to war knowing they were at such a disadvantage, it was nonsense.

“Yes, I had a lot of things said to me in England because of being Argentinean but I would put that down to English black humour. I

would not take it personally. I don't think English people care what was going on in the Falklands war, other than Thatcher, and she is

not the most liked person in the world. English people have been really good to me and they are generally very good to everybody.”

While he has been living away from his home country for most of this millennium, Contepomi has retained close links with Argentina, most tangibly through his work for an organisation supporting former rugby players living with crippling spinal injuries. When Mary McAleese made a state visit to Argentina, the Leinster out-half was photographed with the Irish president at an official function in Buenos Aires.

Come next autumn, however, when Ireland and Argentina meet in their final pool match of the World Cup, all amity will be temporarily suspended.

“Both of us are in the group of death,” he gravely sets the scene. “That's unlucky. Obviously, France are quite tough and they are the local team and they will be quite strong. Ireland are the team that most improved in the last few years and Argentina are the team that have proved in the last few years that they are strong. Perhaps our [Argentina's] ambitions are less than what Ireland and France are expecting of themselves. I know Ireland's target is to get into the semi-finals and France always want to get to the final.

“If the World Cup had been played in November, Ireland probably would have got to the final. I am lucky I play here and I can see how the players have developed. They have a very good squad, not only a good 15. I reckon Ireland will be one of the entertainers of the competition. If they win the pool, I think they will go to the semi-finals but, if they don't win it and come second in the pool, they will meet the All Blacks in the quarter-final.”

Felipe Contepomi has already taken his place in the Irish rugby history books. That inevitable “off day” that awaits every sports person arrived for him at the worst possible time, when Leinster and Munster confronted each other in Lansdowne Road last year in the Heineken Cup semi-final. The famous Latin game-making panache deserted him. He missed a “sitter” of a penalty, failed to make the 10 metres for a re-start and kicked to touch on the full – blunders he was previously thought incapable of committing. Some commentators diagnosed a “mental breakdown” in the normally unflappable Contepomi ignited by a Lansdowne Road aflame with Munster's scarlet.

“The atmosphere was great,” he remembers with gracious under-statement, “but we could not play the game we wanted. Munster had a very good game. It was Munster playing their type of game over our type of game. It's as simple as that. That's the way it's been ever since I came here. They are two such different types of games and whoever can impose their game, they win. I am used to playing away games more than at-home games. With Argentina, I play away games mostly so I don't care what supporters do.”

As for the current Heineken Cup, he is characteristically restrained with his prophesy-making. “When you see the teams that didn't make it through the pools stage, like Toulouse, Gloucester and the Ospreys, once you have got through, anyone can win it. I think we are prepared to have a go and try our best. We are a more mature team than we were last year.”

Having been written into the Irish rugby annals once again last New Year's Eve when he played in the last match at Lansdowne Road between the refurbishers move in, he says: “It's nice to be part of the history of a stadium like Lansdowne Road, but it was an important match for us to continue in the Celtic League with ambition. There was a great atmosphere but it's not that I was carried away on the emotion.”

Last September, he found himself ensconced in a rather alien place for an Argentinean professional rugby player when he was invited to the All-Ireland hurling final in Croke Park and watched what he describes as “one of the best spectacles I ever saw. It was incredible.”

Though he will not get to play in the GAA high temple for the Six Nations, he has not discounted the possibility that he could yet make his debut there.

“It can only be good for Irish sport that Croke Park is open for rugby,” he commends the decision to allow the Six Nations games to be played there, before advocating that it also be opened to Heineken Cup ties. “I know there is a lot of history going on in Croke Park but we are now in 2007 and for one of the best stadiums in Europe, not being able to show it off to the rest of Europe would be a missed opportunity. It would be great to have Croke Park for a quarter-final or a semi-final of the Heineken Cup. It is the third-best stadium in Europe and you can create an incredible atmosphere there.”

If that is ever to happen, it had better happen soon; before Leinster's fly-half and sometime captain departs for home. “I would like my children to be educated in Argentina because that is how I grew up,” he says, preparing to dash off for his evening training session.

No, he adds, he would never dictate to his children whether or not they should play rugby (a sport still not as dangerous as diving or horse-riding, he points out) because they must live their own lives and, besides, “the day comes for us all when we are alone and have no one to tell us what is the right thing to do”.

On his way out of the bar, his quiet attempt to pay for the coffee is waved off like some preposterous notion. He protests. The barman insists. Hands are shaken across the counter.

And he is gone. A sports star today, a doctor tomorrow and an exemplary Christian Brothers' old boy from Buenos Aires whose recorded message on his mobile phone is the sound of his baby daughter laughing.