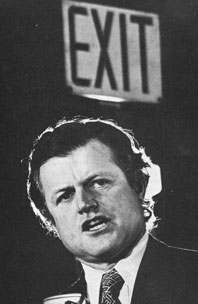

Edward Kennedy: The Last Hurrah

Staff reporter Gene Kerrigan has been through New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Illinois and New York on the campaign trail of Senator Edward Kennedy.

The blinding lights of the TV crews had been burning for over three hours, illuminating an empty rostrum. The waiting crowd had packed tighter and tighter as the latecomers pressed nearer to the stage. Sweat rolled, feet ached, shoulders strained, but nobody dared move to a more comfortable spot for fear of losing a vantage point. The fire marshalls had sealed off the building, nobody else allowed in. A three piece band bopped away annoyingly in a corner of the room. Photographers jostled one another and inched forward to get a better angle, sometimes glancing at their watches as the minutes ticked away towards a deadline.

It was 10 pm, Tuesday, February 26, on the ground floor of Parreseau's, a disused store on Elm Street, Manchester, New Hampshire. The last polling station had closed two hours before and the figures were being totted up for the result of 1980's first major primary election in the fight for the Presidency of the United States. This was Edward Kennedy's election night party. It might have been a victory rally but for the predictions coming from the pundits on the three TV sets at the far side of the room.

"Be ready when I give you the signal", murmured a Kennedy aide to the keyboard player. "You know what to play, don't you?"

"Yeah, yeah, My Wild Irish Something, right?"

The bearded bassist giggled, "How about, I Will Survive?" The keyboard player laughed, the Kennedy aide was not

amused.

Then, finally, the curtains at the back of the room opened, the cheers erupted, and the Senator was walking out, smiling, shaking a hand here and there. Secret Service men materialised, staring icily into the crowd. The band broke into When Irish Eyes Are Smiling. When the cheering died away Kennedy stared gravely down at the audience, patted his tie, touched the microphones briefly and said, "I have a very important announcement to make tonight, to the people of Manchester and New Hampshire."

Then, finally, the curtains at the back of the room opened, the cheers erupted, and the Senator was walking out, smiling, shaking a hand here and there. Secret Service men materialised, staring icily into the crowd. The band broke into When Irish Eyes Are Smiling. When the cheering died away Kennedy stared gravely down at the audience, patted his tie, touched the microphones briefly and said, "I have a very important announcement to make tonight, to the people of Manchester and New Hampshire."

Throughout the crowd there were audible intakes of breath. He was going to do it, here, now. The polls had been bad, the press attacks withering, the incumbent president seemingly invincible. The unexpected uphill fight, the waiting for a break in the Iranian and Afghanistan crises that were helping Carter, the hopes that all was not as bad as it seemed - it all built to this moment. Well, they wouldn't have Kennedy to kick around any more.

Kennedy drew out the pause as the audience became totally silent. Then, his mouth twitched into a mischievous smile as he continued, "I want to announce that tomorrow is my daughter Kara's birthday!" And the crowd screamed in release. A birthday cake appeared, candles flickering, the band played Happy Birthday. The ice broken, the awkwardness of facing his supporters after a third unexpected defeat diffused, Kennedy put it on the record, shouting, his arms swinging up in wide arcs to point off into the distance. "We're going to continue this campaign, down into Massachusetts, on to the Democratic Convention and into the White House!" And the crowd screamed again, the prospect of humiliating surrender postponed if not done away with.

The next day Kennedy did some early morning handshaking in Boston and then flew down to Birmingham, Alabama. Kennedy knew he had no chance in the string of primaries coming up in the South. He would depend on the industrial constituencies of Illinois and New York to rescue his campaign after the defeats of Iowa, Maine and, most important, New Hampshire. His Southern visit was merely a token one, to consolidate the black and liberal support.

A meeting in a downtown hotel was interrupted by a dozen hecklers, one of whom carried a placard saying, "How can you save the country if you couldn't save Mary Jo?" On to a meeting of black Ministers in Montgomery, where Kennedy made an emotional civil rights speech invoking the memory of his dead brothers and his own liberal record. "Every time the roll has been called on those issues which make such a great difference to the quality of life in America, I have been there with all of you ," he thundered, to a chorus of "Amens" and "That's rights".

Then Baptist Pastor Walter Fauntroy, the Democratic Representative for Washington DC, with a long record of involvement in black struggle, rose and urged the audience to support Kennedy in his hour of need. To the obvious embarrassment of Kennedy and the unease of most of the audience, Fauntroy suddenly broke into song.

To dream the impossible dream, To fight the unbeatable foe, To bear with unbearable sorrow ...

Fauntroy's obvious sincerity merged with the grimness of Kennedy's situation and, despite the hamming, the appropriateness of the lyric (from Man of La Mancha) created a palpable pathos amongst the audience.

One man, scorned and covered with scars ...

And Fauntroy pumped every line with the crassness of an Irish lounge singer.

To be willing to give ...

He handed Kennedy a dollar bill.

When there's no more to give He held up an empty wallet.

Two days later, on the last day of February, Kennedy met with his closest advisers for a twelve-hour council of war. For twelve years he had resisted the appeals to raise the Kennedy flag again. Then, at the peak of his Senate career, he had launched his campaign on the Presidential waters - and watched in dismay as it sprang leak after leak and began to slowly sink. The campaign contributions had slowed to a trickle after the Iowa defeat. New Hampshire put the tin hat on it. Now, the previously unthinkable was being spoken aloud. Kennedy might even lose in his home state of Massachusetts primary on March 4. Only four months earlier, Kennedy had led a pathetic Carter in the national polls by 2-1. Then, incredibly, the last of the Kennedy brothers had stumbled, fallen, and now appeared to be crawling doggedly towards the kind of defeat which would finally bury the Kennedy myth.

The war council decided to cut paid campaign staff to one hundred, half the number they had started with, and to reduce pay. Fifty top field organisers were despatched to Illinois, where the campaign was in a shambles. The South would be all but ignored, with no advertising money to be spent in Georgia or Alabama. And 300,000 dollars was to be used for three national half hour television advertisements in an attempt to create a national debate on the issue on which Carter was weakest, the economy.

The defeat in the New Hampshire primary, that peculiar and in many ways grotesque aspect of the American political process, was the clearest indication that more than the vaunted Kennedy charisma was needed if Camelot was not to have heard its last hurrah.

LIVE FREE OR DIE

In the long difficult pregnancy which produces a President for the United States there are about three dozen primary elections. Registered supporters of each party vote in separate elections to send delegates to national Conventions in the summer to decide on a candidate. These delegates are selected to represent a candidate in proportion to the number of votes received by the candidate in the primary election. The theory is that the citizens not only vote to choose between the candidates in the General Election in November but also have a prior say in the choice of candidates. The original idea was to take the choice of candidate out of the proverbial smoke filled rooms of the party machines.

New Hampshire is the first and most important primary in that all the registered supporters of the parties, plus citizens registered as Independent, can vote. The earlier delegate selections, in Iowa and Maine, are merely caucuses

of party officials. This small state, in which just a quarter of a million people voted on February 26, has an inordinate influence on the selection of candidates, an influence of which it is ferociously proud and which it adamantly defends.

In 1971, the Florida legislature moved its primary to the second Tuesday in March, the traditional date for the New Hampshire primary. New Hampshire promptly brought its primary forward to the first Tuesday in March. In 1975, Statute 58:I was passed, shifting the date to "the first Tuesday in March or on the Tuesday immediately preceding the date on which any other New England state shall hold a similar election", petulantly but effectively blocking an attempt by Massachusetts and Vermont to hold their primaries on the same day as New Hampshire.

Since 1952 no candidate has become President without winning his party's primary in New Hampshire. Though the state sends only a handful of delegates to each Convention reputations are made and broken in the snows of New Hampshire. President Truman lost in 1952 and did not seek re-election. Without a record 23,000 write-in votes in the 1956 primary Richard Nixon would probably have been forced to step down as Eisenhower's vice-President - and out of national politics. In 1960 John Kennedy displayed an unbeatable strength in New Hampshire which assured him his party's backing. In 1968 Eugene McCarthy's unexpectedly strong showing here forced President Johnson out of the race and drew Robert Kennedy into contention. George McGovern's strong finish against a sagging Ed Muskie in 1972 gave him the national prominence necessary to make a credible bid for the nomination. And it was in New Hampshire that Jimmy Carter emerged from nowhere in 1976 to head the poll and make his successful bid for the Democratic nomination.

A victory or unexpectedly strong showing in New Hampshire creates the supply of media attention and financial support necessary to fuel the campaign for the road to the national Convention in the summer. Everyone loves a winner. And it all happens in a peculiar state with just 0.36 per cent of the US population.

Every car licence plate in New Hampshire is embossed with the state slogan, "Live Free Or Die", a blustering gesture to liberty attributed to War of Independence hero General John Stark. In modern political terms the slogan represents a dislike of Federal interference and a powerful and conservative individualism. This is the only state in the US with no sales or income tax. Publicly funded facilities are, in consequence, sparse. Public transport, for instance, stops at 6 pm. It is one of the few states where registered Republicans outnumber Democrats, and with no large cities and no significant proportion of black voters is extremely unrepresentative of the Democratic Party. Yet a bad loss here can ensure that a candidate is knocked out of the race before reaching the bigger, more representative states. Contributions dry up as people don't see the point of contributing money to a loser. The media pours cold water on the candidacy. Party officials draw back from throwing their support to someone who looks a loser and give their organisational support to someone more likely to be able to deliver patronage from the White House.

A road safety sign just inside the Southern border of the state gives a wry and hopefully self-mocking expression of New Hampshirians' conservatism. It advises that making a child wear a seatbelt "saves our little tax deduction".

THE MAN WITH THE WHITE HAT

On the morning of Monday February 25, the day before the New Hampshire primary, the state's largest selling

newspaper, The Manchester Union Leader, appeared with a two-inch deep advertisement running across the top of the front page. The ad in red print, said, "Sure I have a sense of humour", says George Bush, "Bill Loeb's editorials always give me a kick!" Republican contender George Bush was paying 1,300 dollars for the pleasure of taking a kick back at the paper and publisher which had harassed him viciously for almost two months. That paper had more than a little to do with the outcome of the New Hampshire election.

The Union Leader is a journalistic legend. Published by septuagenarian William Loeb and carrying a personally signed publisher's editorial each day, the paper is as idiosyncratic as the state which it influences.

Loeb was a friend and supporter of Senator Joe McCarthy, the drunken anti-communist crusader whose 1950s' smears ravaged the civil rights of thousands because of their real or alleged political beliefs. Though McCarthy bas long been discredited Loeb still describes him as "the man with the white hat going into the Western bar to clear out the bad guys." Loeb appears to believe that he has inherited the white hat of the long-dead McCarthy.

In an editorial in February 1977 he described the TV series Roots as a Russian conspiracy to brainwash Americans. In 1973, in an editorial entitled "Let's Go After Our Oil", he advocated an economic blockade of Arab countries. And if that didn't work, he proposed, the Arabs mould be asked, "How would you like to have us bomb your sacred cities of Mecca or Medina out of existence?" In 1972 he wrote: "This newspaper would urge the Nixon administration to level North Vietnam - dikes, Hanoi, Haiphong, populated areas, everything." In 1975 he advocated that the Vietnamese be told pull back "beyond the peace line or we will obliterate one of their cities by conventional or nuclear weapons, whatever is the handiest."

Loeb's trigger happiness is not reserved for foreigners. In 1971 he advocated that those vandals who smash picnic tables at state parks should be shot on the spot. At the height of the anti-war protests he demanded that "rioters .. should be shot in the legs with shotguns and birdshot. If that doesn't work then machine guns should be used." Untiring in his daily rants against communists, women's liberation, liberals, the metric system, homosexuals and short skis, Loeb is undoubtedly a certifiable nut and could be relegated to the status of a curiosity if he and his paper did not have such an influence on the population of New Hampshire and, in particular, its largest town, Manchester.

Underneath the George Bush advertisement on the front page of the Union Leader on that election eve morning ran a large denunciatory headline, "George Bush Is a Liberal". There were three other anti-Bush headlines on the front

page. Inside the paper there were another four anti-Bush articles.

Loeb was backing Ronald Reagan, the 69 year old exGovernor of California, for the Republican nomination, as he did in 1976. Reagan lost then to Gerald Ford and Loeb has a habit of backing losers. His influence tends to be negative, turning voters off particular candidates rather than convincing them of the merits of his favourites. Loeb was, predictably, scathing about Kennedy, dismissing him as not only a liberal but also "a coward". However, his efforts were concentrated on promoting Reagan by denigrating his Republican rivals. The first target was Philip Crane, a young right wing conservative. Crane's politics being too close to Reagan's to be susceptible to ideological attack, Loeb took the personal angle. Last year a series of derogatory articles alleged that Crane was a heavy drinker and a playboy and that his wife had a drinking problem. That took the wind out of Crane's sails in conservative New Hampshire.

The attack switched to George Bush after he unexpectedly took a majority of delegates at the Iowa caucuses in January and became a threat to Reagan. Loeb went to work with a vengeance. In a major assault in the three days leading up to the vote Loeb published seventeen anti-Bush articles, another seventeen pro-Reagan and five anti-Kennedy. Many of the other candidates simply were not mentioned. One of the most outrageous anti-Kennedy attacks was a call to the gun lobby to counter Kennedy's stand on gun control. Loeb's editorial advised that this was their chance to get Kennedy. The headline read, "Golden Opportunity for Gun Owners", and the illustration for the piece was a small red target. In the circumstances in which the unspoken fear in the Kennedy camp is that there is a soul brother of Lee Oswald or Sirhan out there waiting to complete the Kennedy hat-trick the editorial was sick.

Though some commentators suggest that Loeb's polemics are no longer taken seriously by his readers the antiBush onslaught clearly had an effect. In the Union Leader's home base, Manchester, where 18 per cent of the New Hampshire votes are cast, Reagan defeated Bush by 8-1. Reagan's private polls showed subsequently that 48 per cent of Republican voters changed their minds in the three weeks before the election and one third did so in the week before the ballot, the period of Loeb's onslaught.

At Kennedy's election night rally in Parraseau's store on Elm Street, Charles Margelot, a Union Leader photographer inched his way along the barrier towards the stage as the crowd waited for Kennedy to arrive. Two Kennedy supporters acting as stewards conferred.

"That guy down there, with the glasses, don't let him any closer."

"Don't worry, I'm keeping an eye on him." ''Walk all over him if you have to."

Next morning the Union Leader's main photo of the rally was supplied by UPI, with Margelot's photo, shot from a distance through a forest of arms, tucked away on an inside page. The petty revenge would not have bothered Loeb. His favourite had trounced Bush by 2-1 in New Hampshire and the coward Kennedy was limping along.

DEAR VOTER

DEAR VOTER

The founding mother came to the microphone. Rose Kennedy, at 89 sounded her age, her voice quivering and strained. It was February 22, the forty-eighth birthday of her youngest son, Ted, the only one of her four sons to live to that age. Before her, around a couple of dozen large tables, sat about two hundred elderly people, many of them wearing blue and white Kennedy stickers. The senior citizens of Manchester were gathered this morning at the Carpenter Community Centre to celebrate Ted Kennedy's birthday. Some wore stickers saying "Seniors for Kennedy".

The old people had waited patiently for over an hour for Kennedy to arrive, their free meal long since digested, a panoply of journalists gathered behind a barrier at the end of the room to observe the ritual. An old man helped pass the time by banging out "America The Beautiful" and "Danny Boy" on a battered and out of tune piano. A social worker approached one of the TV technicians and asked that the harsh lights be switched off until the Senator arrived as some old people had complained that their eyes were hurting.

"Sure, sure, no problems, just a moment." The lights stayed on.

Finally, the Senator was there, making a joke about being allowed a wish on his birthday and couldn't they all guess what that wish would be? Then he introduced his mother to speak as one senior citizen to her peers.

"I know you supported my other sons in other times and I am grateful to you for supporting Ted. I think if you had nine children ... "

Kennedy, sitting a couple of feet behind his mother's right elbow, muttered, "Don't forget to tell them to vote on Tuesday".

" ... I'd hope the ninth would give you the courage and all the wonderful qualities that Ted has given me and all the members of our family ... "

"Don't forget Tuesday, remind them to vote."

" ... when we've been faced at difficult times by crises and the deaths of our three other children who met their fate in such unexpected ways."

As the crowd applauded Kennedy rose, took his mother's elbow and leaned over to whisper into her ear. She turned back to the microphone, "Oh, and don't forget to vote on Tuesday!"

If the road to the Presidency requires you to verbally nudge your aged mother within earshot of a dozen party officials, Secret Service agents and photographers, then so be it. Ten minutes later, having cut a cake presented to him by the senior citizens, Kennedy was speeding to West High School, this time presenting his young son Ted Jr. to speak to his peers, a horde of whistling students. And telling the students that he had been told that he was allowed a wish on his birthday and couldn't they all guess what that wish would be? And cutting the birthday cake presented by the students and speeding off to the next of the fifty-two "birthday celebrations" arranged throughout New Hampshire by the Kennedy Democrats.

Back at the Kennedy headquarters on Elm Street, volunteers were grouped around tables writing personal letters to voters whom they had never met. Each volunteer had a duplicated master letter from which would be copied by hand a chatty spiel. "If you had told me three weeks ago that I would be door-to-door canvassing through New Hampshire I wouldn't have believed you. But here I am - working for Ted Kennedy. Working hard. Things are made a little easier when I meet people like you who take the time to listen and I thank you for that. Just like you I'm not a professional politician, I am not used to this kind of thing ... "

At the weekend several busloads of volunteers from New York and Massachusetts, when finished their canvassing, were assigned the task of letter writing. Working on the theory that a handwritten personal letter was less likely to be consigned to the dustbin along with the rest of the avalanche of election literature, canvassed voters would receive these follow-up epistles. Some volunteers were given master copies of letters to write to people whom they had met, along with an instruction: "Remember that only you will have had the personal contact with these voters to know what 'personal notes' to include in this letter (i.e., Nice meeting your children, petting your dog, etc.)".

Similar instructions were distributed to the dozens of volunteers assigned to ring one voter after another with appeals on Kennedy's behalf. Such instructions always included a reminder to "keep your message to each voter brief, to be polite at all times, and to avoid arguments", and to "thank every voter .. you represent Sen. Kennedy so it is important to be polite in every situation." It didn't always work out that way. At an early stage in the campaign a local middle-ranking Democrat received a telephone appeal for support. Replying that he was undecided between Carter and Kennedy he received the appropriate thank you and a hope that he would do the right thing. As he was about to replace the phone he heard a muttered, "Asshole". He delivered his influence and about fifty votes to Carter.

The letter-writing and phone calling were part of a massive operation to solve the logistical problem of identifying the level of support in the state, working on the voters whose support was lukewarm, and "pulling" the vote on election day. The voters were coded according to their response. Favourable to Kennedy got you a "1", leaning towards him a "2", undecided a "3" and opposed a "4". The "Fours" were ignored, the "Ones" inveigled to volunteer and the "twos and threes" inundated with calls and literature. These categories were subdivided into interest groups and sent appropriate "issue sheets" on health, the elderly, energy, women, gun control or foreign policy. In the last few days before the vote the "threes" were ignored and all the emphasis put on getting the "ones and twos" to the polling stations.

Frank Weaver, Manchester Volunteer Co-ordinator, spread his hands in appeal. "I just want to help out in whatever way I can. I'll be there at seven in the morning". One of the paid campaign workers was explaining that he would not really be needed until noon, when Kennedy made an appearance at a local school.

"It's for crowd control, you can be a big help with that. Now, I can't promise that you'll get a handshake or anything, he'll just be rushing through."

Frank shook his head at her failure to understand.

"Look, I don't want anything like that. I believe in this man, I want to help him." His earnest face, with tired eyes, drooping moustache, looked sad. "He's the last liberal hope. "

Frank can quote from the speeches of John and Robert Kennedy, solemnly, sincerely. "Ask not what your country ....". When Ted Kennedy went off the bridge at Chappaquidick in June 1969 Frank immediately wrote to the Senator pledging his allegiance. He received an acknowledgement which he still treasures. He worked for Kennedy's Senate election in 1970, for McGovern in 1972 and now he was working in the one he had waited for for twelve years, writing, phoning, discussing strategy until the small hours of the morning.

The volunteers and paid staff in New Hampshire, as in all states, were a mixture of locals and out of state enthusiasts, sometimes an uneasy mix. There were the professional politicos like Carl Wagner and Mike Ford, the highly respected field organisers. The Maineiacs, the crew who had followed the campaign from Maine after managing to rescue a respectable defeat out of a stumbling candidacy. Kennedy Senate staff from Washington. Volunteers from Texas and Georgia, from New York and Ohio, drawn to the Kennedy flag, Robert Diller, a young black from Brooklyn, arrived for the last few days of the campaign, drawn by a need to oppose Carter's conservatism.

"I ain't gonna stay in this here town one hour longer than necessary. I wouldn'a come up here near the place if it hadn'a been for Kennedy. If Carter gets back in that's it, man. We've had twelve years of conservative government, with Nixon, Ford and now Carter. He's a Republican, man. And thirteen is a bad number. The people ain't gonna take it. They'll be out on the streets with guns, man, that's what'll happen. We have had eee-nough. A Democrat shouldn't be a conservative, man, if you're a conservative then you should be a Republican. John Connally, you know John Connally? He was a Democrat, he was with John Kennedy, he was in the car. Hell, he got shot with Kennedy. Then he found that his views were getting more conservative, so he changed over, he became a Republican. And I can understand that, man, I can respect that. But that motherfuckin' Carter, man, he's something else. He's a turkey. If he gets back in that is it, man. Four more years of conservative government? There'll be a revolution in this country, that's what'll happen."

When Sirhan Sirhan pumped a bullet into Bobby Kennedy's head in 1968 he fired a shot that started Ted Kennedy down the Presidential road. Kennedy resisted the calls to take his brother's place in the 1968 race, the agony of losing a second brother to the political assassination too new. Chappaquidick poisoned 1972. In 1976 his family problems took him out of contention. Then the Draft Kennedy movement began last year in New Hampshire when Jimmy Carter displayed his ineptitude. On November 8 last year Kennedy finally announced that the time had come. Three days earlier the fifty hostages had been seized at the American Embassy in Iran.

When Jimmy Carter announced last summer that he would take on Kennedy and "whip his ass" it seemed to compound his lack of sense. In November the polls showed that even Jerry Browne would defeat Carter in Massachusetts. It seemed that Kennedy would stroll it. Then the increasing outrage about Iran was fuelled by the Russian invasion of Afghanistan and Carter benefited from the loyalty given to a leader in a time of crisis.

When Kennedy hit the campaign trail he walked into a blinding light which exposed every flaw in his candidacy. Before Chappaquidick Kennedy's drinking and his affairs were common knowledge to the press but were unreported. In the wake of the accident they were strewn across the front pages. Similarly, the sleeping dogs were let lie until Kennedy declared his intention to run. Then the old sins were dredged up again. In a CBS interview with Roger Mudd Kennedy appeared stiff and defensive about Chappaquidick . As a result the polls showed a high percentage of the electorate distrusted him. Magazine articles appeared challenging Kennedy's account of the accident. Initially his campaign had stressed vaguely the theme of "leadership" as an alternative to Carter's incompetence. As the country rallied to Carter in the face of the Ayatollah, Kennedy found that more and more it was being demanded that he define why he was running, to show that simply being a Kennedy was not enough any more. In a country growing increasingly more conservative and summoning up an indignation about Iran which is rapidly washing away the shame of its conduct and defeat in Vietnam, Kennedy found himself forced to define a Presidential platform based on a liberalism which is gone out of fashion in the United States.

There have been a few occasions in his seventeen years in the Senate when Kennedy abandoned the traditional liberal stance. For instance in 1968 and 1970 he capitulated to public hysteria about law and order and supported repressive legislation, the Safe Streets Act and the Organised Crime Bill. On Israel his stance is that of a right wing hawk in deference to his otherwise liberal Jewish constituency. For the past decade, however, Kennedy for the most part has been a classic liberal in American terms, on Vietnam, Watergate, civil rights and bussing, women, homosexuals, labour laws, gun control, and welfare. In recent years he has proposed legislation to civilise America's draconian free enterprise health system.

Moreover, Ted Kennedy acquired a political ability that far outshone that of either of his brothers, John or Robert. "Chappaquidick", commented historian Arthur Schlesinger, "put the iron in Edward Kennedy's soul". However, while there is a constituency for such liberalism for a Senator it makes a poor steed in a Presidential race in which the winner must successfully appeal to a multitude of opposing and antagonistic interest groups and constituencies.

Joss Wall had been out canvassing for several hours, now he was doing a phone canvass. Tall, with that fresh faced American handsomeness, Joss had long stopped denying on doorsteps that he was one of the Kennedy sons. Now he slumped down in his chair, tired and a bit demoralised.

"Hey, Harry, what's Kennedy's position on marijuana?" Harry Owens, a Dublin telephonist who spent his holidays working for Kennedy in New Hampshire and was in charge of the issue sheets, crossed the room.

"Let's see. He wants the penalties for possession reduced, but he's not an advocate of it. I think that's the best way to put it. Why, are you having trouble?"

"Just some guy, thinks Kennedy goes too far." Joss paused. "I wish sometimes he'd pull back a little on things like that."

Harry grinned, "That's what he stands for. You know, you could always tell them that as far as you know he doesn't smoke it."

DIRTY TRICKS

The TV screen shows Amy Carter, the President's daughter, doing her homework. Her father's voice comes on.

"I don't think there's any way you can separate the responsibilities of a husband or a father and a basic human being from that of being a good President. What I do in the White House is to maintain a good family life, which I consider to be crucial to being a good President". Carter is no slouch at putting the boot into Kennedy's well-publicised family problems. Another TV advert uses the theme, "You don't have to wonder if he's telling the truth." Such dirty tricks combine with a judicious use of the powers of an incumbent President.

Prior to his 1976 campaign Carter had for two years assiduously courted the New Hampshire Democrats, constantly visiting the state, sleeping in supporter's houses, engaging in the eye-to-eye retail politics which such a small state demands. This time, insisting that the Iranian crisis keeps him White Housebound, Carter brought the political mountains of New Hampshire to Washington. A stream of local politicos received much-prized Presidential invitations in the run up to the election and a stream of Federal money flowed in the opposite direction. For instance, Transport Secretary Neil Goldschmidt breezed into town with an announcement of a 34 million dollars highway grant.

Winter Olympic champions being interviewed for live TV at Lake Placid found a phone ringing at their elbow with the drawling tones of President Jimmy getting into action. Olympic medal winners were invited to lunch at the White House and when ice star Eric Heiden used the opportunity to hand Carter a petition from athletes opposing the boycott of the Moscow Olympics he found it hurriedly brushed aside, while Jimmy continued grinning for me cameras. On election day in New Hampshire a car load of STOP supporters fanned out through Manchester, handing out anti-Kennedy literature. STOP stands for Stop Teddy On President. The organisation is one of several conservative groups which wage independent campaigns against Kennedy. Others include the Kennedy Truth Squad and the National Rifle Association.

The latter organisation, with a national membership of 12 million, has been particularly vociferous, taking anti-Kennedy adverts in newspapers and on radio and showering New Hampshire with bumper stickers saying, "If Kennedy wins ... you lose." As such groups are independent of any candidate conservative individuals and organisations can contribute the maximum donation allowable under the campaign laws to their candidate, and then make further donations to groups which attack their candidate's prime opponent. At the peak of his success against Reagan, George Bush suddenly found himself the target of similar groups. However, as a former director of the CIA he couldn't have been too worried. His campaign staff included two dozen ex-CIA agents.

On the Saturday before the election a group of large individuals arrived at the Kennedy HQ on Elm Street, to support the campaign. They worked together around a table, not fraternising with the other campaign workers, collating issue sheets and stacking the canvass kits issued to each volunteer. When a TV crew visited the HQ that afternoon the large individuals all took a simultaneous coffee break, disappearing behind a partition at the back of the room. Later in the evening a photographer sitting at a nearby table, his camera dangling, was approached by one of the group, a towering man whose bulk gave the impression that his clothes were too small, that his cuffs stopped several inches short of his wrists.

"Nice camera, fella, what kind is it? Thirty-five millimetre, huh? Yeah, that's a good one, must've cost a few bucks." He stacked a few more canvass kits and then returned.

"Listen, buddy, don't take pictures around us, okay?"

"Why?"

"Just don't take any, right? Not if you like your camera".

The large individuals were union members from Maryland, supporters of Labour For Kennedy. They had been sent to New Hampshire to help out. If this was done openly their union-paid fares and expenses would count as a contribution to Kennedy and would be marked off against the maximum he could solicit. So they worked incognito. The right restrictions on the allowable election contributions and expenditure, brought in after the President For Sale atmosphere of the Nixon era, resulted in such rule-stretching to evade the spirit of the law. Another common tactic in all camps was to arrange for a candidate to end a day's handshaking near the border of a state. That way the overnight stay could be spent in a neighbouring state and the hotel and sundry expenses incurred would not count as election expenditure under the rules.

Technical knockouts were scored by both Kennedy and Reagan in removing opponents from the New York ballot. New York has the tightest requirements for a prospective candidate, who must prove that he has sufficient support

to make a credible stand by collecting several thousand signatures. Kennedy's staff had Brown removed from the ballot by proving to the satisfaction of the election officials that many of the signatures collected by Brown's supporters were illegible. Similarly, Reagan wiped Bush's name off six of the fifteen delegates slates in New York, using the same method.

The neatest dirty trick of the campaign so far was pulled by Reagan. A New Hampshire paper, the Nashua Telegraph, had invited the two Republican front runners, Reagan and Bush, to debate before an audience on Saturday February 22. Officials of the Federal Election Commission ruled that since the debate featured only two of the candidates the cost of holding it would count as an election contribution if paid by the paper. Reagan promptly coughed up the required 3,500 dollars the debate would cost. At that point he did not appear bothered that his other Republican comrades would be excluded.

Several days before the debate a private poll told Reagan that his support was draining and he saw his chance when fellow Republicans John Anderson and Robert Dole sent a telegram to the Nashua Telegraph protesting at being excluded. At 11am on the morning of the debate the other Republicans received hand-delivered letters from Reagan inviting them to partake in the debate. By 2 pm Reagan had been told by the Nashua Telegraph that the paper had drawn up specific questions for himself and Bush and there was no way these would be arbitrarily divided among any other participants. Reagan did not convey this information to his fellow candidates and did not inform Bush of his invitations until moments before the debate began.

When the shoal of candidates walked on stage Bush froze. He sat toying with his notes throughout the ensuing confrontation, conveying at once an impression of snobbery and of inability to handle an embarrassing situation. The Telegraph executive editor, Jon Breen, tried to convince the other candidates to leave, and when Reagan began making a speech called, "Turn off Mr. Reagan's microphone!" Reagan reacted in true Western hero style by grasping the microphone, squaring his jaw and thundering, "I paid for this microphone, Mr. Breen!"

Standing at the back of the stage, Anderson, Dole, Baker and Crane burst into applause along with the audience. And the picture conveyed to the electorate was one of a strong Reagan defending four hapless and ineffective colleagues in the face of an arrogant Breen and an elitist and ineffective Bush. Bush tried vainly to stay afloat in the avalanche of bad coverage which followed, by pointing out that he was merely adhering to the Telegraph ruling. Philip Crane announced the next day that he had been tricked and used by Reagan. The other three had enough sense to bite on the bullet and not compound the image which had been created of their weakness and Reagan's strength.

NEW HAMPSHIRE AFTERMATH

Shortly after dawn on the day after the New Hampshire primary Ted Kennedy was out shaking hands in Massachusetts, bringing nods of approval from his rank and file supporters. The same approval was not forthcoming for some of his staff. Reports that his Campaign is less than streamlined have not been exaggerated. A hundred New Hampshire volunteers contacted in the early days were not re-contacted for the campaign. Many committed Kennedy supporters grew angry at receiving several phone calls and letters when their support had been already assured. One of these was actually working in the Kennedy HQ. Many volunteers felt that their patiently collected data about the issues bothering the voters was not being conveyed to Kennedy.

The campaign lacked a unifying force, someome to take responsibility for co-ordinating activity. Symptomatically, on at least two occasions the HQ doors were left unlocked, with lights blazing, in the small hours of the morning, for want of someone with a clear responsibility for security. Three days before the election, volunteers working on the ground floor were angered to discover at 3 am that the upstairs staff had gone to a party to celebrate the birthday of state campaign co-ordinator Dennis Kanin. The anger was not so much at being excluded from the celebration, more at the fact that supposedly key workers would take time off in such a crucial period.

A thousand minor complaints about the details of the campaign were compounded by Kennedy's own ineptitude on the stump. While he can deliver a set-piece speech impeccably, preferably at a victory celebration, Ted Kennedy has not got the glib articulateness demanded of those who seek high office. The speeches drafted for him, specifically applying to a region, can be fumbled. "The price of gas here in New England is, uh, now .. 1.23 dollars a gallon .. uh, I think . . ." Answering questions, he has a tendency to wander, his sentences dragging out.

At the Franklin Pierce Law Centre in Concord, New Hampshire, about fifty students were turned away from a meeting, while Kennedy staffers and reporters waltzed past the queue. One middle-aged woman, staffer, with the wit to see the tactlessness of the situation, shouted in a loud voice, "I want to give up my seat for a student, hey, you up there, let the students in, I'm giving up my seat." The rest of the students were directed to a separate room where they could watch Kennedy on closed-circuit TV. "Make sure you talk loud when you ask questions", they gibed. Even here they were corralled by secret service agents, and when a promised Kennedy appearance in the TV room did not materialise the cynicism increased.

Lacking a good organisation, Kennedy could not depend on his policies to carry New Hampshire and there was no great surprise when he trailed Carter by over ten thousand votes. The one issue which hurt Kennedy more than all the others was gun control, the right of a citizen to own a firearm. Though Kennedy argued that his position was the same as Carter's, that rifles should merely be registered and that only Saturday Night Specials, hand guns with no other purpose than to kill humans, should be banned, he suffered from the attacks of the National Rifle Association and the individualism of New Hamshirians. In the final days of the campaign Kennedy attempted to woo supporters of Jerry Brown by issuing contradictory leaflets claiming at first that Brown supported drafting young people into the army, and later claiming that Kennedy and Brown were at one on the issues of nuclear power and the draft and that a vote for Brown would be wasted.

New Hampshire was the turning point in Ronald Reagan's campaign. He had lost badly to George Bush in Iowa after following the advice of his campaign manager, John Sears, to keep a low profile. Reagan had spent a total of only forty-eight hours campaigning in Iowa, with Sears arguing that extensive handshaking would give people "the idea that he's an ordinary man like the rest of us." Reagan ignored Sears' advice in New Hampshire and shook as many hands as would shake. At 2 p.m. on election day he summoned Sears and handed him a press statement. it announced that Sears had just resigned.

Sears was the first casualty of New Hampshire - there were more to follow. John Connally, ignoring the state and concentrating on the South, realised too late that he had let Reagan build up a head of steam which brought the former actor thundering down into the Southern States, blasting aside all of Connally's careful preparations. Connally retired from the race having spent 11 million dollars winning enough votes to give him one single delegate.

Robert Dole and Howard Baker, having pulled miniscule votes in New Hampshire, were disregarded in the subsequent primaries. Philip Crane stubbornly hung on, as though New Hampshire had never happened. His supporters, however, deserted in droves to the Reagan camp.

When Gerald Ford announced, on March 2, that he was waiting for "an honest to God, bona fide, broad based group" of Republicans to ask him to enter the race and head off Reagan there was an embarrassing silence. Republicans who months earlier had pleaded in vain with Ford to stand had since been hopping on to the Reagan bandwagon. Now they were being asked to again change forces in mid-election. The episode merely confirmed Ford's legendary ineptitude.

On the night before the New Hampshire election Jerry Brown faced his supporters in the Chateau lounge on Hanover St. "I'm a movement", he croaked. He jibed at Kennedy supporters in the crowd. "Your campaign is over! Join us tonight, tomorrow, next week - we don't care - he's finished!"

Less than twenty four hours later Brown pulled out of several primaries and headed off to Wisconsin to make a last stand on, appropriately enough, April 1. A rousing blustering performer and a practiced opportunist on political issues, Brown had simply failed to produce. Even worse than Connally he had not won even one delegate and henceforth seemed little more than a pest.

The media balloon which had carried George Bush aloft after his early triumph over Reagan burst. Bush grew irritable and snappy with reporters, his campaign mauled by New Hampshire.

John Anderson was coming up on the outside - having pulled an unexpected 10 per cent of the vote and subsequently coming close to winning in Massachussetts and Vermont. The moral and practical support flowed to the Republican Lone Ranger, the underdog who just might bite his way into the big league. In all the fuss, few bothered to examine Anderson's supposedly liberal record. In fact he is a hawk on defence spending and supported the Vietnam war, has economic policies' scarcely less conservative than Reagan's and has a long and consistent anti-union record. In addition, in the Senate he has been a virtual spokesman for the nuclear industry. On a small number of social issues - gun control, women's rights, abortion, the draft - he has been to a greater or lesser extent liberal. His main asset is in directness of speech, an image of not shaping his opinions to catch votes. There is a constituency for such a stance and Anderson systematically works the campuses, pulling even young people who dislike some of his policies but admire his directness.

It is perhaps symbolic of the American political system that the candidate drawing surprise support for his apparent honesty, has based his campaign slogan, ("The Anderson Difference") on a TV commercial which tries to convince viewers that one brand of asprin is superior to another, ("The Anacin Difference").

Ted Kennedy stared gravely from the TV screen, telling Massachusetts voters that he felt priviliged to have represented them in the Senate for 17 years. "I've spent a third of my life representing you". Now, on the eve of the election, "I've come home to ask your help."

"Kennedy volunteers are better because they have enthusiasm," read the poster in the Boston HQ. It was untrue. Until the results came in experienced Massachusetts pols were genuinely worried that Kennedy might lose even his own state. The lack of co-ordination continued, the same unease about Chappaquidick, the same inability to arouse a debate on the real issues. But the people of Massachusetts supported their own man against Carter. Kennedy's votes came from all classes and ethnic groups, even those who had previously reviled him for his unpopular stand on bussing. It was a regional vote rather than an ideological one. In the ballroom of the Park Plaza Hotel in Boston Kennedy shouted out the results to his supporters, his voice relieved and joyful at having at long last a victory to display from the lonely rostrum.

Last October Jimmy Carter went to Chicago to attend a Democratic fundraiser. At the height of his unpopularity, he was grateful for an apparent promise of support at the function from Mayor Jane Byrne, who announced, "I would vote without hesitancy to renominate our present leader." Carter was not to know that earlier that day Byrne had received a telegram from Ted Kennedy: "I have known you and loved you and Chicago longer."

When Kennedy formally entered the race two weeks later Byrne reneged on her promise to Carter and promised the support of the infamous Cook County political machine, built by the late Mayor Daley, to Kennedy.

Shrugging Byrne's knife out of his back, Carter went to work and bitter battle was joined. Federal funds slated for Chicago began to dry up. Transport Secretary Neil Goldschmidt (last seen buying votes with Federal bounty in New Hampshire) announced that since he had suddenly "lost confidence" in the Mayor he would review the scheduled highway grants. Byrne was no less ruthless. Ward leaders and precinct captains of the Democratic Party, most of whom have city jobs controlled by the Mayor, were warned that failure to work for Kennedy would jeopardise their jobs. The machine seized up. The resulting vibrations not only rattled Kennedy's already shakey campaign but will probably dislodge Byrne come the next Mayoral elections.

For the past four months Mayor Byrne has provoked widespread anger by deliberately engaging in head-on confrontation with the unions. First the transit workers (and Byrne set an example by riding the first strike-breaking train), then the teachers, then the firefighters.

On St. Patrick's Day Byrne arranged that Kennedy would head the, city's parade with Carter's float placed 176th in line. As the parade began Ted and Joan Kennedy walked beside Byrne. As the boos and catcalls of the citizens rang out for their Mayor the Kennedys began to hang back. Ten feet, twenty, thirty, forty - as the boos intensified the Kennedy's put a proportioned distance between them and the Mayor. To no avail. Kennedy was trounced, taking only 14 delegates to Carter's 165. He immediately headed off to New York to prepare for a crucial showdown.

'WHERE YOU GONNA BE WEDNESDAY?"

John Gage's bearded face broke into smile. "It's Saturday morning, let's go to the Bronx!" There were three campaigning days left to the New York primary and Gage, a senior Kennedy aide, was lapsing into irony. Two busloads of reporters were trailing Kennedy to the South Bronx, a grim disaster area to the north of Manhattan. Earlier that morning, while Gage was announcing the Senator's schedule for Tuesday, election day, a reporter cracked, "Where you gonna be Wednesday, John?" Gage smiled ruefully and then said deadpan that he wasn't sure but he thought that the Senator would be in Washington all day Wednesday.

There was an air of Wistfulness about those last three days. Reporters read the latest Harris poll, which showed Carter leading by almost thirty per cent, and shaking their heads in bemusement asked Kennedy did he not think that carrying on would merely hurt Carter and help the Republicans. The mathematics were simple enough. Carter had won 702 delegates so far and Kennedy 210. The target for victory is 1,666. To win, Kennedy would now need to take two delegates for every one going to Carter in the remaining primaries, the exact reverse of the present trend.

Kennedy suggested briefly that he had a new strategy. If enough of Carter's delegates could be convinced to abstain in the first ballot at the Convention, denying Carter a first ballot victory, those delegates might then be won to vote for Kennedy in the second ballot. Kennedy was soon disabused of this pseudo-sophisticated nonsense. Delegates are legally bound to vote for the candidate whom they have been elected to represent and cannot abstain.

Without drawing over sixty per cent of the New York vote, against all the odds, Kennedy would be finished. Although drained of funds, Kennedy could count on sufficient contributions to continue a shoe-string campaign in order to harass Carter. Beyond that Kennedy's only hope was to persevere on the chance that some traumatic occurance, such as the execution of the American hostages in Iran, would change the prevailing political winds.

Kennedy declared stubbornly that he would hang on in the race right up to the convention with the aim of keeping the liberal flag flying in the Democratic Party. In the face of almost certain defeat Kennedy gave the impression of a man determined to prove his strengths of principle, maturity and courage. As one defeat followed another he acquired a bounce and cheerfulness, almost as if he was relieved that now that he had been seen to make the expected run he could go back to doing what he was best at - defending his own New Deal version of American liberalism.

On the sixteenth floor of the Halloran House Hotel on Central Park, Kennedy kicked off a 9 a.m. press conference before heading for the Bronx. The President of New York City Council, Carol Bellamy, had just announced her support for Kennedy. She spoke almost resignedly of the need to stand on principle, quoting Kennedy on "swimming against the tide", and expressed little of the usual confidence that usually accompanies such endorsements. When she was asked to predict the outcome in New York she smiled and replied, "It will be ... very close, I think," while Kennedy merely grinned and shook his head.

New York's Mayor Koch, Governor Hugh Carey and most of the city's top Democrats had sniffed the wind and were backing Carter. Bellamy is the city's second highest elected official, the best Kennedy could attract.

An hour later Kennedy was standing on a heap of rubble in the South Bronx, surrounded by a hoard of reporters and a handful of party officials. The highest ranking of these, Herman Badillo, shielding Kennedy from the rain with an umbrella, could claim to be a former deputy mayor.

A sprinkling of local people turned out to hear Kennedy speak of the poverty of the area. Standing on the waste ground of Charlotte St., amid a scene of unimaginable desolation, Kennedy recalled that Carter had stood on that very spot in 1977 and promised to rebuild the area. Nothing had been done. The cops stamping their feet outnumbered the locals who peered through the blinding rain and the storm of reporters to catch a glimpse of Kennedy. Aides hurriedly conferred and decided to abandon a visit to Long Island and a flight to New Haven. The Senator would drive instead of flying - he hadn't been having too much luck with planes lately.

At the start of the campaign Kennedy had hired a jet plane for his entourage of aides and reporters. It ate up a million dollars of his campaign funds, with parking fees alone costing a daily 5,000 dollars. As his campaign faltered the plane was grounded and he began using commercial flights. The day before the Bronx visit Kennedy had sat impatiently at the La Guardia Airport, his flight delayed. Plane delays that day caused him to miss a meeting of 1500 people and an important TV interview. Through the rain streaked windows at the airport he could see the cavalcade of Vice-President Mondale, on his way to campaign for Carter, sweeping through to board a Presidential jet.

Fritz Mondale stepped forward to the rostrum in the banquet room of the Sheridan Centre Hotel, a grin splitting his face as he waited for the applause to die down.

"I stand before you tonight representing the President of the United States ... "

A hiss, a murmer and, encouraged, the black tie audience began to boo without inhibition, forcing Mondale to halt his speech. Each time he mentioned Carter he drew the same reaction. At the end of the speech, just to show there was nothing personal, the crowd gave Mondale a standing ovation and began a chant of "Mondale for President".

Mondale had been trying to patch up the leaking Jewish vote. Thirty-two per cent of New York's Democratic voters are Jewish and Carter's ineptitude in supporting and then disowning the anti-Israeli vote at the UN became his biggest problem, drawing a picket to his New York HQ and constant barracking of his "surrogates". It prompted a flurry of pseudo-activity. Begin and Sadat received surprise invitations to Washington. A celebration of the anniversary of Carter's Middle East initiative at Camp David was brought forward by three days to be held before the primary. Film of the Camp David meeting was repeatedly used in Carter TV adverts. And Carter was prompted to briefly abandon his stance of being too busy dealing with Iran to campaign, when he offered interviews to five local TV stations.

The other major problem for Carter in New York was the impending budget cuts which would drastically effect the already troubled economy and social services of the city. He dealt with that by simply refusing to disclose the extent of the cuts before the primary .

The Bnai Jeshurun synagogue on the upper west side of Manhattan is 155 years old. Amazingly ornate, the walls and ceiling superbly crafted, it is the centrepiece of the life of Rabbi William Berkowitz. For 29 years he has been hosting a series of "Dialogues" each Sunday afternoon in which he, in front of a large audience, discusses issues of faith and morality with invited guests. Kennedy's schedule had been adjusted on the last Sunday before the election to allow him to be Berkowitz's guest. Ostensibly Berkowitz had invited all of the candidates to appear in his "Dialogue" - in fact the scheduling was so arranged that only Kennedy could appear. The overflow audience of over two thousand erupted in applause when Kennedy entered. A woman rushed forward and held up a child to the Senator. Kennedy looked almost puzzled and tentatively, almost regretfully, gave the child a papal-like pat on the head.

The "Dialogue" consisted of Berkowitz throwing soft balls for Kennedy to hit for six. "Your late and unforgettable brother, John, wrote a book, Profiles In Courage - if you were to write a sequel which men and women of courage would be included?" Which gave Kennedy an opportunity to say how much he admired people "whose lives are inspired by making an important contribution to society".

Some of the questions were grotesque in their striving to make it necessary for Kennedy to play up to hi audience.

"What is that you fmd great about the Jewish people? Who are some of the great Jews you have known?"

There was an audible stir among the audience and several gasps at the crassness of the question. Kennedy began a long rambling eulogy on the Jewish commitment to family life, with which he totally agreed. Then it was time to put the boot into Cater.

"At this very moment", said Berkowitz, "Mr. Carter is celebrating his Middle East policy with twelve hundred guests on the White House lawn. How do you feel about Carter's Middle East policy? And about the appropriateness in view of the hostage situation, of holding such a party at this time?" Subtlety is not Berkowitz's strong suit. The occasion did, however, give Kennedy an opportunity to hammer home his commitment to Israel ("A land of honey, where each man has his own fig tree") and to pour salt in Carter's wounds.

Kennedy put most of his energy into campaigning in Jewish, Black and Hispanic communities. He spent little of his time in those districts with a high proportion of Catholics, normally a strong Kennedy constituency. So far in the campaign Catholic voters had expressed strong disapproval of Kennedy due to his marriage problems and Chappaquidick. While Kennedy was appearing at Bnai Jeshumn, Fritz Mondale was being photographed shaking hands with Cardinal Cook.

Craig Peters of Esquire magazine held his head in mock agony "God you should see what I have written - it is coming out tomorrow the lines I wrote! About how he talks about his deact brothers and the voters boo, and he talks

about inflation and they holler, and he asks for their vote and they are silent. O God don't read it please, don't read it!"

Crushed into a second floor room of the Halloran Hotel at Kennedy's New York victory Press conference, the reporters were asking one another how things could change so quickly. In the second row a group was discussing the importance of the news that seven out of ten psychics had predicted a Kennedy victory.

The man from the Washington Post drawls "Well, I'll just say the cognescenti said it all along. No I can't really go with that one. How about the entire state of New York was high on something today. No? Don't worry, I'll think of something clever."

There really wasn't anything clever to say. The polls had shown that Carter was losing the confidence of voters - but also that the confidence was not transferring to Kennedy. The Jewish vote could count for something, the shakey New York economy for something else, but how then to explain Connecticut.

Kennedy himself was cautious at the press conference, merely joking "I like this trend better than the last trend." Cold statistics of a New York and Connecticut victory were that he still had less than half the number of delegates Carter had, 402 to 846, and had closed the gap by a mere 48 delegates. Kennedy could not be sure, and will not be for another month, if his March 25 victory was a sign that he had fmally dumped the Chappaquidick albatross. Or was he just being used to send a message of warning from the voters to Carter.

The message wasn't lost on Carter. He had declined an invitation to a democratic dinner function to be held the night after the New York election, claiming he was too busy dealing with Iran. As the election results came in he changed his mind and decided he could leave the White House for a few hours to talk to party members. When Joan Kennedy walked on stage, her shiny purple costume glittering under TV lights, someone shouted "Well, look at that!" She positioned herself carefully a few inches behind and to the left of her husband. Each time she looked at him and smiled there was the sound of camera shutters clicking in unison like, a flock of birds taking off. At the end of the conference, a reporter called out, "Hey, Joan, how do you feel?" "I am very happy, I feel like singing!".

"Go ahead!"

And to the cheers of the reporters she broke into song,

"I like New York in March …..How about August?"

There are five months and sixteen Primaries left before the Democratic Convention in New York in August. If Kennedy does as well in all of these as he did in New York he will still lose the nomination. He would need to be able to capitalise much more decisively on Carter's draining prestige before he could overtake the lead, built up by the President over the past few months. He had so far spent only one day in Wisconsin campaigning for the April first primary and had planned to go there for only one more day. After New York his aides said his schedule was fluid and that might change. Wisconsin has a high proportion of dairy farmers, well pleased with the Carter policies which have kept milk prices up, so Kennedy was not expecting much support there. His sights are on Pennsylvania on April 22 with its 185 delegates.

As Kennedy left the press conference to go to a private room to be interviewed by Walter Cronkite for CBS, several

dozen of his younger supporters were marching up Lexington Avenue towards the Halloran chanting, "Ken-ned.y, Ken-ned-y." Among them was Robert Diller from Brooklyn who had in New Hampshire predicted guns on the streets if Carter was re-elected "We whup his ass," he roared, "We whup his ass! What's that peanutpicking punk saying now?"

A few minutes later Walter Cronkite was finishing a congratulatory interview with Kennedy, saying "Thank you very much, President Kennedy." As the camera pulled away from him, Kennedy leans back and laughs, "President, Hey!"

Some time before announcing his candidacy Kennedy was approached by a group of party elders who urged him not to run against an incumbent Democratic President. His reply was, "Thanks, but my father always said if it's on the table, take it". Aware of the mud he would have to walk through once his candidacy was announced, Kennedy made calculated moves to clean up his image. Campaign volunteers received instructions on behaviour. Kennedy himself slimmed down by twenty pounds. He took coaching in replying to questions after his first few disastrous attempts.

Although separated for two years his wife, Joan, gamely rallied to the cause and punters were invited to meet "Mrs. Edward M. Kennedy". Leaving the stage at his Boston victory rally Kennedy suddenly realised the husbandly duty of a candidate and turned back to escort her off. Only occasionally did Joan falter or betray nervousness in her roll. When the flat smack of firecrackers sounded at the Patrick's Day parade in Chicago she spun around in obvious panic.

Twelve year old Patrick Kennedy comes to the microphone. A small, thin child, his fair hair falling over his forehead. Patrick is shy and uncertain in public. Occasionally his face lights up when he sees a crowd cheering or placard waving. That's his daddy up there arousing all that enthusiasm. Mostly Patrick stays in the background, grinning shyly and twisting his fingers together when someone makes a fuss of him.

Tonight, as on several other occasions, he is brought to the centre of the stage and encouraged to read a few words to the crowd. This is one of those early defeats for his father but that's not Patrick's problem. He is rigid with fright and embarrassment. A thousand eyes watch his every move, the pitiless TV lights exposing him to millions. He begins reading an innocuous few words of thanks on his father's behalf. His voice is trembling, his hands shaking, his face trying desperately to smile through his terror. He falters, stops. Teddy Jr. steps forward smiling the Kennedy smile, exuding the Kennedy confidence - "As my little brother was saying so confidently ... ", the crowd laughs.

At the back of the stage Kara Kennedy, Patrick's older sister, is hugging him, smiling, whispering a few words of comfort. Before New York a supporter consoled herself by noting that a Kennedy defeat was not the end. There's Ted Jr. and Joe Jr. and lots more to come. "Patrick, well, he's lovely, but ... anyway they were a very fruitful family, thank God".

At the back of the stage little Patrick Kennedy stands alone now, tears coursing down his cheeks, his mother's encouraging smiles not sufficient to dispel his shame at failing to carry out a routine function of the Kennedy males.