Derek Hill and the Golden Section

Derek Hill prefers his west of Ireland landscapes, but spends most of his time painting portraits.

The "Golden Section", in art, is obtained by dividing a line unequally, so that the smaller section is to the larger as the larger is to the whole. Theoretically, the ratio produced is "ideal". It gives harmony in composition wherever applied. It is expressive of the diversity of forces in art, the underlying regulators, the eternal conflicts of form, texture, colour, resolved by laws which have changed little if at all since Giotto or Giorgione hammered them out.

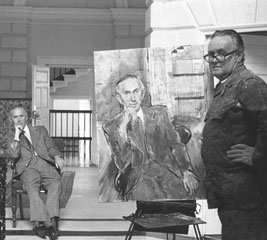

lt was Derek Hill who explained the "Golden Section" to me, standing in front of one of his own paintings. It was not vanity that caused him to invoke the possibility of an ideal proportion imposed on his own work, for though he loves to be admired he is not a vain man; it was the fluent, educated, socially sophisticated, widely travelled, much commissioned artist seeking to explain the grammar of his art. And he does it so well.

He is big and plump; not quite eccentric in his dress, he manages an easy mixture of tweedy off-handedness and gentlemanly elegance. And though in his sixtyfourth year, the cherubic, boyish face, the ready smile, the friendly eyes, retain comfortably that inner resource of enthusiasm keeping Time at bay. It breaks down at times. No one who knows Derek Hill has escaped altogether the agonised voice complaining of someone's derelections - often one's own - and few have failed to respond with the balm of appeasement or conciliation. After all, he is an artist; he has the right to be temperamental.

He is big and plump; not quite eccentric in his dress, he manages an easy mixture of tweedy off-handedness and gentlemanly elegance. And though in his sixtyfourth year, the cherubic, boyish face, the ready smile, the friendly eyes, retain comfortably that inner resource of enthusiasm keeping Time at bay. It breaks down at times. No one who knows Derek Hill has escaped altogether the agonised voice complaining of someone's derelections - often one's own - and few have failed to respond with the balm of appeasement or conciliation. After all, he is an artist; he has the right to be temperamental.

There are deeper agonies, however. Derek Hill is pursued by all the innate problems faced by the portrait painter. Moving from country to country, palace to parliament, stately home to castle, university to university, he does not only carry with him the encumberance of his own personality, but has to create, formalise and make permanent the personalities of other people.

For thousands of people the most permanent version of Archbishop Charles McQuaid is Derek Hill's version in the entrance to St. Vincent's Hospital. And to the next generation of Trinity College students, his portrait of Provost Lyons is not only the "official" version; it also marks a departure in style into an informality, a fluidity in the handling of paint, a more orchestrated compounding of the figure of Dr Lyons with his surroundings; it is a painting more than a portrait. "I think of myself," says Hill, "as a painter who does landscapes and people. I would prefer to be doing landscapes rather than portraits; I believe I feel more for landscapes than I do for portraits. But I spend more of my time painting people."

The "Golden Section"? Is the relationship of Derek Hill's landscapes to his portraits what his portraits are to the whole of his output as a painter? Is there some kind of ideal ratio between the cherubic, tweedy landscape artist, lugging his easel and paints across the stormy seas between Donegal and Tory Island, in order to paint the craggy cliffs there, and the traditional society catalyst, painting the heir to the throne of England for Trinity College, Cambridge, or the Earl of Drogheda for the offices of the Financial Times? In so far as anything is ideal, in so far as anything golden touches the burnt umbra of our lives, then Derek Hill has achieved, through paint, that essential resin that knits together all the diversities present in a career that epitomises the fragmented evolution of his particular generation.

Born in Southampton, educated at Marlborough School, he went off to Munich in 1933, of all years, to sample the Bauhaus influences rather than to engage in politics. In the mid-thirties he went to Paris, again to study art, but also to do stage designing, He went on to do more of this in Vienna, and then travelled extensively, through Russia, Japan, China, Burma and Siam, settling back in Hampshire for the second world war.

Derek Hill claims a diversity of painters as "influences". With a wide and eloquent sweep of his arm he embraces the Impressionists, Corot, Constable, Bonnard, Vuillard, Picasso, the Euston Road school, particularly Victor Pasmore. But the eloquent sweep needs to be gently interrupted. Hill's debt to Pasmore is substantial. But in nineteenth century English painting he probably owes more to Landseer than he does to Constable, and in the twentieth century more to Giorgio Morandi than to the Post-Impressionists or indeed to Picasso, whose impact on Derek Hill has been mercifully light.

He first came to Ireland in 1946, drawn by a variety of forces, among them the broad compulsions of Celtic art. But what he actually did was to paint the seas and cliffs of the west, particularly Galway and Mayo. He was befriended by Bernard Berenson, and spent much of the early fifties at I Tatti, outside Florence. But in 1954 he bought a house at Churchhill, in Donegal, and more or less since then has made the north west his home, though with the inevitable movement around the world, writing books about Islamic architecture, and painting portraits. Yehudi Menuhin, Osbert Lancaster, John Betjeman, Erskine Childers, Isiaih Berlin, Lord Longford and the explorer, Wilfred Thesiger; these are a small selection of subjects exhibited at his one-man show at Marlborough Fine Art in London in the winter of 1978-79.

He first came to Ireland in 1946, drawn by a variety of forces, among them the broad compulsions of Celtic art. But what he actually did was to paint the seas and cliffs of the west, particularly Galway and Mayo. He was befriended by Bernard Berenson, and spent much of the early fifties at I Tatti, outside Florence. But in 1954 he bought a house at Churchhill, in Donegal, and more or less since then has made the north west his home, though with the inevitable movement around the world, writing books about Islamic architecture, and painting portraits. Yehudi Menuhin, Osbert Lancaster, John Betjeman, Erskine Childers, Isiaih Berlin, Lord Longford and the explorer, Wilfred Thesiger; these are a small selection of subjects exhibited at his one-man show at Marlborough Fine Art in London in the winter of 1978-79.

He agonises a bit over the strings of names, reminding one of the fine and splendid paintings he has done of Tory Islanders, men like John Dixon and Andy Shields. But relentlessly one is drawn back to that strange and artificial encounter between portraitist and subject, a gap of a few feet filled with the tensions of revelation and concealment. Derek Hill claims a kind of amateur status. His fees, by the standards of other practitioners like Graham Sutherland (would you believe £20,000 for a portrait?), are low.

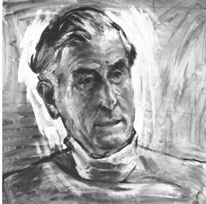

Because of this he is known as "Peanuts" Hill. He laughs excessively at the impact of this, but at the same time is faintly embarrassed. What he really does, in his portrait painting, is to please himself. And one sees it most in the sketches; the brilliant penetration in the Thesiger sketches, the degree of revelation about character in the back of Arthur Rubinstein's head, the remarkable head of L.P. Hartley, the pinched sadness in his own self-portrait.

When he can he makes the gruesome bus journey to Donegal, drives out in his battered motor car beneath the shadow of Errigal, sets up his easel, and with a kind of boyish confidence still in the teeth of time, paints on. Wherever he is, it is the delivery of the paint to canvas that unifies all his actions.