Squeeze my middle

It's a disorienting and frequently disconcerting sensation to live between two countries on the European periphery and witness the striking similarities but also the glaring differences. It is not that things are much better in Spain than in Ireland; for many they are worse. But what there is, to a far greater degree than in Ireland, is the availability of media productions that are a significant countervailing force to the dominant media machinery - which treats the destruction of labour rights, the dismantling of the welfare state, the privatisation of public services and the immiseration of the population as mere administrative facts at worst and necessary measures for national recovery worthy of enthusiastic backing for the best part.

No such luck in Ireland, where all the newspapers and radio stations are right-wing.

I read some of the pieces in the Irish Times's 'Squeezed Middle' series this week. In one of the inaugural pieces, Dan O'Brien wrote the following of the bourgeoisie, which he praised effusively:

'who else made the modern world?'

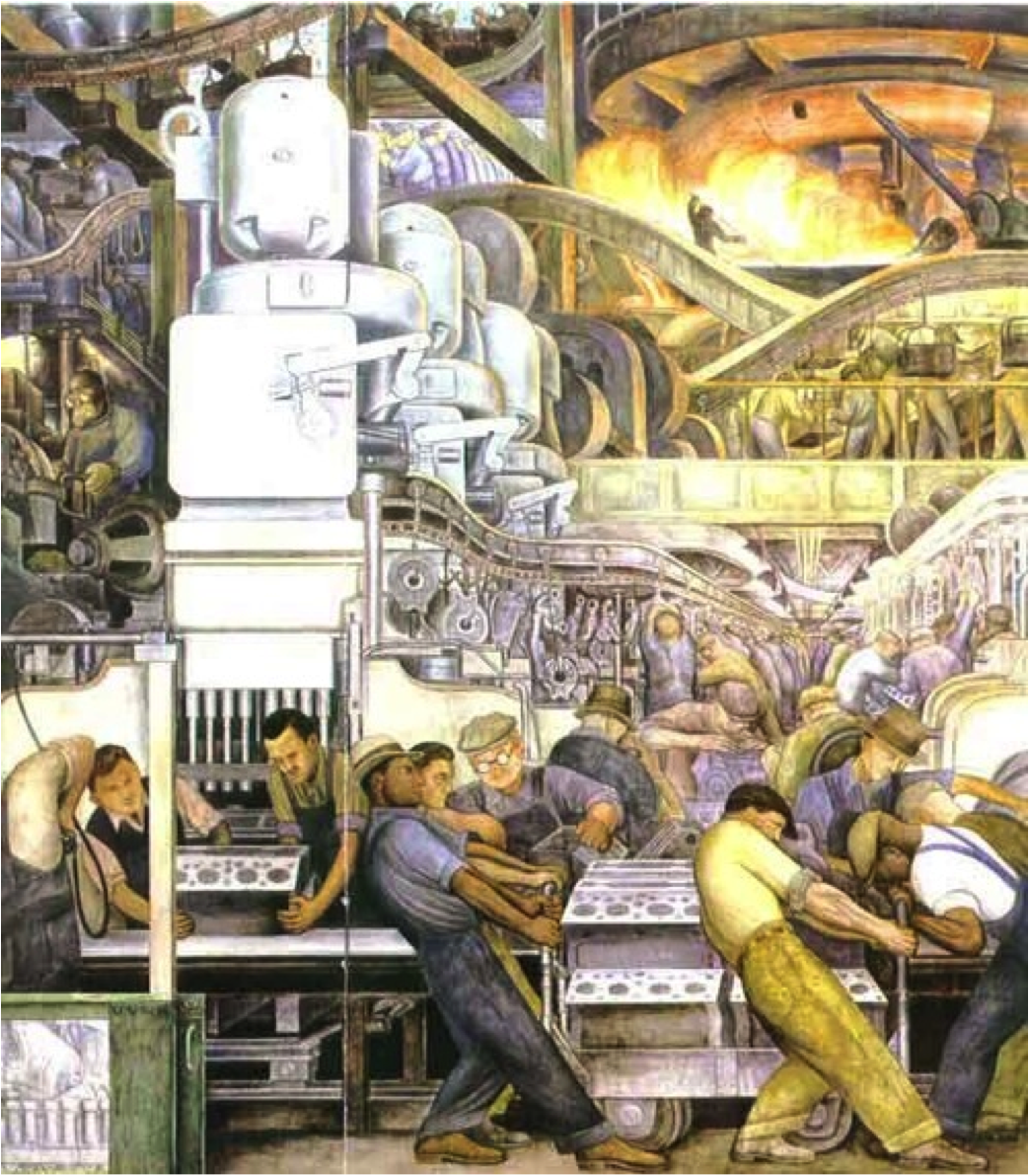

There was no mention of the modern working class that the bourgeoisie had called into existence.

In O'Brien's view of history, it was the bourgeoisie who worked in the canals, the mines, the shipyards, the car factories, textile factories, it was the bourgeoisie who harvested all the crops, cooked all the meals, raised all the children, and built all the homes and aircraft hangars and office blocks.

And - if his characterisation is anything to go by - they were all a happy cross between Marcel Proust and Margaret Thatcher.

The ‘ethical advances, from the abolition of slavery and capital punishment to the curbing of cruelty to animals and the smacking of children’, trumpeted by O'Brien, sit ill at ease with the vicious cruelty inflicted, to use one example in a world saturated by them, on the people of Greece, in order that German bankers can fret over whether or not their diamonds have been ethically sourced.

In the Squeezed Middle series (the question of who is doing the 'squeezing' never comes into it, nor does whatever lies below the middle), we can discern a newspaper trying to fashion a depoliticised readership (a headline from one of last week’s features: 'The best attitude is just to get on with it') with a newfound sense of common identity, forged amid recession, which can be easily and productively targeted by potential advertisers.

Moreover we can see the continuous erasure of labour - basic matters such as pay, working conditions, conflicts of interests, the threat of unemployment - from the domain of politics and public discourse.

To say nothing, of course, of class as a social relation, not an affectation.

In a piece not of the Squeezed Middle series, but worth reading alongside it, Conor Brady, former Irish Times editor, wrote about how 'good journalism, for all its faults, interacts with public institutions to ensure a fuller and healthier democracy'.

Yet the Squeezed Middle series suggests that this is neither the time nor the place for political activity on the part of its targeted readership. This isn't all that surprising: for the Irish Times, politics rarely appears as the task of the citizen; rather, all that is required from the citizen is a vote every few years. Politics is something that one has to be Inside, like the title of its weekly political correspondent column implies.

'We live in a representative democracy...It is as simple as that', wrote its political correspondent on 4 February in an attempt to ward off the prospect of a referendum. But it is not as simple as that. Even if we were to accept the definition of the Republic of Ireland as a representative democracy, which is arguable given the fact that in any major political decision the representation that counts is the one made on behalf of banks and speculators, it is a heavily mediated representation, in which our information and our very ideas about politics are developed, and our reflexes manipulated, by mass media institutions.

Thus, instead of creating political engagement on the part of citizens, concerns are fostered and appetites are stimulated: for privileges in health care and education in a country that never had a proper post-war national health service, not least because its privately-educated elite was dead against it; for consumer bargains, and for psychological readjustment (read: submission) to the inevitable war of all against all, which is intended to unfold as Ireland falls to the bottom of EU states for government general expenditure by 2015.

So private health care is described as a middle class 'staple': as one interviewee was quoted as saying, 'You’re going into a public system that isn’t geared for it... And then I want to scream and roar at the Government, “Where’s your overhaul from the five-point plan, the one where everyone was going to have private health insurance?”’

Questions such as why the public system is not geared to look after the public are as welcome as a fart in a lift.

When it comes to education, the Irish Times correspondent reports that 'private education may have become unaffordable for some, but schools such as Belvedere and Blackrock are continuing to show a surge in numbers'.

Oh for the days when everyone could afford private education at Belvedere! Of course, what is meant by 'some' is 'some of our ideal readership'. And no link is drawn, of course, between the 'roll back in much of the progress made in Irish education recently', and the political choices made by people such as Brian Lenihan (Belvedere) and Ruairi Quinn (Blackrock), and the untold billions of public money spent on bank bailouts, NAMA and associated services, and how the beneficiaries of such transfers of wealth are precisely those people most likely to send their children to exclusive private schools.

The depoliticising thrust of the Squeezed Middle series is none more apparent than in the article on 'positivity' by Maureen Gaffney, which exists in a universe where no-one has read Smile or Die by Barbara Ehrenreich:

The depoliticising thrust of the Squeezed Middle series is none more apparent than in the article on 'positivity' by Maureen Gaffney, which exists in a universe where no-one has read Smile or Die by Barbara Ehrenreich:

If one descended from outer space, one might expect a newspaper interested in a fuller and healthier democracy to address some of the threats to democracy of the day: such as the concentration of immense decisive power in the hands of financial elites, the confiscation of prosperity and imposition of misery by institutions such as the European Central Bank, the European Commission and the International Monetary Fund, which are not accountable to any popular power.

These are questions of immense importance, which demand collective discussion and the development of collective solutions. In their stead, we get the cheery voluntarism of the unitary and isolated bourgeois subject, in which exploitation is of no importance and solidarity is unheard of, as hawked by Gaffney.

The function of the Irish Times, along with that of other Irish newspapers, is to present a political programme, the imposition of mass unemployment and the destruction of the welfare state, which is being conducted in the interests of the wealthiest groups in Irish society, as a moral imperative, divinely ordained.

For its succesful execution, every traditional petty bourgeois prejudice must be mobilised, and questions of class conflict have to be extinguished - whether by denying they exist ('we're all middle class now' - O'Brien); by displacing them - through mobilising resentment against grotesques like Sean Fitzpatrick or faceless mandarins in the civil service and presenting the public sector as a whole as a ruling class; and by fostering a common identity by creating common enemies: welfare recipients, migrants...

Common to all this is ensuring that the figure of the worker counts for nothing. For these institutions it is a matter of realising the dream of every bourgeoisie - as Pierre Bourdieu identified - which is to have a bourgeoisie without a proletariat.

Faced with this, it is self-evident that there is an urgent need to develop media alternatives that undermine the normalised discourse of submission to 'the markets' and accepting one's fate. In this regard I think this post by Tom Stokes, on the Irish Labour Press at the beginning of the 20th Century, is highly relevant.

As I was saying earlier, there is a greater degree of media diversity in Spain, and this prevents public discourse from being entirely normalised to a TINA rhythm. Of note here is the left-leaning daily newspaper Público. Its edition from Sunday 5 February featured an article by Luis García Montero, titled 'Unemployment as a business', in which he sketched out the way in which the Spanish government was fanning the flames of unemployment, using the alibi of deficit reduction, because this served the interests of financial speculators. It was interesting, I think, how García Montero observes that the fear generated by a policy of keeping unemployment deliberately high means people focus on 'survival, not the defence of rights'. By contrast, The Irish Times, as part of its Squeezed Middle series, had a four part Recession Survival Guide.

The best response to that sort of thing, I think, is this: {jathumbnailoff}

Dave Lordan- Surviving the recession @ #occupydamestreet from Paula Geraghty on Vimeo.