Charlie and the Press Gang

A review of the relationship between Haughey and the media, and the allegations of press bias.

The question was: once they'd voted Charlie out, would they hang on to vote in the new leader? Do that and we could be here all night. No way, they'll do that tomorrow or the next day. Lord, I hope it's Dessie. He's a nasty little get, but at least he's got reasons for wanting to be Taoiseach. Not like the because-it's-there merchants. Dessie you could have some fun with.

Michael O'Kennedy? A used light bulb on legs.

John Wilson? He'd deliver his budgets in Greek. They still wouldn't add up.

Gerry Collins? When he was young he used play the flute with his nose. Enough said.

The journalists had been hanging around Leinster House for almost twelve hours, waiting for word to come down about the margin of votes by which Charlie had been ejected. A man from breakfast TV was slumped in an armchair, feet up. A colleague told him: "I know we're bored with this story, but we've got to cover it." The man from breakfast TV slumped down further. "Don't worry about me. I'm a coiled spring." He yawned.

The sound of roaring leaked into the front hall of Leinster House. The crowd at the gate were howling. The coiled springs sprung. Journalists who had been following the story all day, all week, didn't know what was going on until a Haughey supporter suddenly appeared in their midst, screaming the result and abuse in equal measure. The journalists were asking each other what the guy had said. Charlie won?

The sound of roaring leaked into the front hall of Leinster House. The crowd at the gate were howling. The coiled springs sprung. Journalists who had been following the story all day, all week, didn't know what was going on until a Haughey supporter suddenly appeared in their midst, screaming the result and abuse in equal measure. The journalists were asking each other what the guy had said. Charlie won?

Later on, RTE's Phil Crotty was down at the gate, asking the Haugheyites how they felt. Then she asked them what they thought of the media coverage of the battle. They stuttered in outrage. A TV crew came along and went through the same routine and had to quickly shuffle from one side of the crowd to another as one man spewed out the kind of language you're not allowed to put on TV.

The Haugheyites had a new target, one to be abused with the fervour previously reserved for discussion of Charlie McCreevy, his seed, breed and generation. The press was trying to bury their man, the press was unfair, the press was the enemy. They accepted this new article of faith as readily as they have long accepted that Charlie will deliver unto them the promised land of the fourth green field. And they're as right about one as they are about the other.

Election time and what you do is get schedules, lists of meetings, venues and times for press conferences, direct line numbers to call for any sudden developments or change of plans. And Charlie goes one way, Garret goes another, and journalists run alongside them. Sometimes journalists are allocated to one leader, stick with him throughout the campaign, sometimes they switch around. Garret is favourite. He's easy to cover. But Charlie is more exciting, you don't know when he might just lash out and clock someone or suddenly take a flying leap and start biting the furniture.

With Garret there's a press bus and he'll always get on and chat and discuss the latest poll and tell stories about the time he worked in Aer Lingus. He's friendly. Comes across as a nice guy. Sometimes he's asked a question and he mumbles and thinks and then waffles and you know he's as confused about some things as most people are. Put it this way: Garret doesn't get smart with you.

Charlie seldom has a press bus. If he has, so what - he doesn't get on it. Next town you come to he might suddenly jump into a helicopter and leave you stranded. He doesn't chat. He says things to you. And you feel that before he said them he carefully decided what he was going to say. Six or seven hours on the road, faithfully taking down his every word on how he wants the good people of Ireland to rally round and give him a mandate to fulfill his destiny - and he might suddenly throw a moody and start barking. The kind of thing that happens - there's a function and an aide comes over and says you'd better not take any pictures because if Charlie sees that camera he'll throw the head altogether.

Garret is nice to be with. He makes it easy. He's open - and even if inside he's wishing this shower would bugger off, he grins and bears it. He chats and grins with Brian Farrell, and he chats and grins with the cub from the Ballymacslob Gazette. Charlie carefully chooses those he'll chat and grin with - as opposed to those he'll chat and grin at. At the end of a campaign a whole lot of people really like Garret. And a whole lot of people find Charlie irritating. The fact that one man is open and warm and another closed and cold is a matter of personality. It shouldn't matter, if politics is being coveted. But the politicians make Irish politics a matter of personalities. Inevitably it creeps into the copy.

Famous occation. Des O'Malley speaking at a press conference in the Burlington, microphone in hand. And, incredibly, Charlie's hand starts inching along the table, slowly, inexorably, towards the microphone - until Dessie just has to hand it back, it's getting embarrassing. And Charlie passes the mike to Martin O'Donoghue and as someone asks O'Donoghue if he really thinks Knock Airport should be built Charlie, incredibly, mutters, "Say yes!"

Garret mumbles, makes false starts, is sometimes so obviously trying to evade a question that you feel half embarrassed, half like throwing a chair at him. Charlie sits right down, looks you dead in the eye and says "Black is white". And when you say, "But, Mr Haughey ... ", he looks you dead in the eye again, lowers the thermostat on his vocal chords and says, "Black is white.''' Charlie has made so many u-turns, has acted so arrogantly in doing so, has so patently manipulated other members of his party, that it gets written about. Journalists say, "This man is saying black is white. This man is telling. Martin O'Donoghue to say black is white."

All of that - the fact that the man is distant and cold and manipulative, and that there are glaring inconsistencies in his policy record - is the bread. The jam is the continuous scandals. Okay, maybe you get bored with the Pat O'Connor story, don't worry, the MacArthur scandal will be along soon. And the Doherty scandal, Mark I. And Mark II. '

Yes, there is a bias in the media. Yes, Charlie makes a jam sandwich that just asks to be eaten. Yes, it's hard to find nice things to write about him. Yes, there is an uncommonly large number of nasty things, embarrassing occasions, in which he has been involved. And they get written about. It's called telling it like you see it.

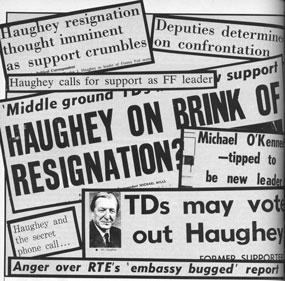

It was like someone pressed a button. One minute it's all Sean Doherty and hasn't he got a neck on him like a jockey's behind. And would you believe this stuff about McSharry and O'Donoghue? And, presto, the next minute those stories are dropped and it's all about how Charlie is going down for the third time. When Charlie first became leader of Fianna Fail he was the media's darling. One morning Tim Pat Coogan and Douglas Gageby went on radio to vie for the honour of loving him most. Then, the simple facts of his disastrous, accident-prone, contradiction-ridden, scandal-plagued regime got him a bad press. That was what was happening, that was what got written about.

When the third push against Charlie appeared, journalists responded accordingly. The point of departure was Will They Get Charlie Out This Time? It was, perhaps, given the events of the past couple of years, inevitable. But wrong. The point of departure should have been somewhere else. Somewhere in the. midst of that murky story involving O'Donoghue, somewhere in the inconsistencies of the "middle ground". People like Ben Briscoe should have been asked why they were kissing Charlie on all four cheeks in October - and what had changed to make them want to slap him now.

When the third push against Charlie appeared, journalists responded accordingly. The point of departure was Will They Get Charlie Out This Time? It was, perhaps, given the events of the past couple of years, inevitable. But wrong. The point of departure should have been somewhere else. Somewhere in the. midst of that murky story involving O'Donoghue, somewhere in the inconsistencies of the "middle ground". People like Ben Briscoe should have been asked why they were kissing Charlie on all four cheeks in October - and what had changed to make them want to slap him now.

There is no solid bloc comprising "the media". There are ranks and files. The political correspondents, a handful of senior journalists, make the running in determining what "the story" is. They more readily get the lead story, front page, they most often set the direction in which the other reporters follow. The other reporters collect "hard news" or chase TDs or party officials for comment or do descriptive pieces - all of which, on a story like the Fianna Fail antics, becomes the wake behind the ship which the political correspondents are steering.

Due to the nature of the split in Fianna Fail several of the political correspondents have established close relations with the anti-Haughey factions, far closer than their relations with the Haugheyites. There are various reasons for this. For a start, the dissidents are of the type more likely to lunch in Dobbins. They are more in tune with the social, cultural and political tendencies of some of the political correspondents. The dissidents have more to gain, are pushing a cause, are more open to pumping about problems.

Haugheyites tend to swear loyalty to that great man Char-less Jay Haw‡hee and say things like "no problem". They have more to hide. Also, let's face it, some of them look funny. They howl, their loyalty is primeval. Many of them are at a vast remove from the interests of the political correspondents. How many political correspondents can swap country and western anecdotes with Donie Cassidy? (Some.)

On the night of Charlie's great triumph there were jokes floating around about Peter Murtagh of the Irish Times. Mock complaints about here we are standing around for hours when we could air be down the pub if it wasn't for yer man and his bloody phone tap stories. And the story started with real, live baddies and goodies. And when some Fianna Fail TDs became genuinely confused about where their loyalties should lie and others began thinking that now might be a good time to abandon Charlie's bandwagon and find one with more potential, the political correspondents took over and that became "the story". And the political correspondents, it turned out, couldn't count. They got it wrong, not for the first time, and sometimes they get things right. Win some, lose some.

The bias is towards the sexy side of the story. When is this incredible guy, who screws up on everything except his own survival, going to cop it? And, because the emphasis is on that, and because everything else flows in the wake of those pursuing that side of the story, other things are played down. The inconsistencies of the dissidents, the paucity of political difference between Haughey and his enemies. And, not least, the about turns of Garret FitzGerald, constitutional crusader in a papal sash.

The media have been hard on Charlie. Quite properly. There are a lot of hard things going on. They've got it about right, where Charlie is concerned, apart from the erratic surges away from the main story and in pursuit of the interests of the political correspondents. What it needs is not so much softening on Charlie as hardening on just about everyone else.