Capitalist rioters don't wear hoodies

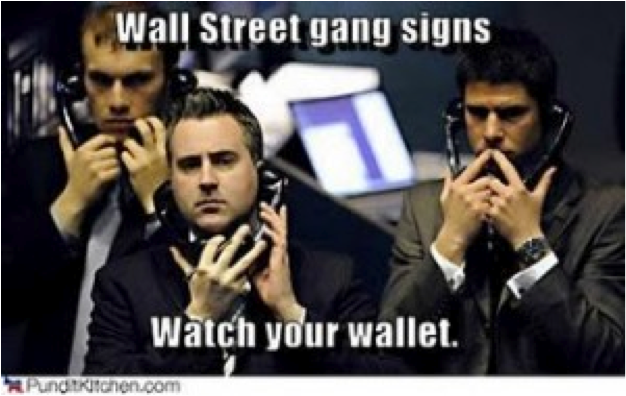

The global media has been nervously covering two simultaneous forms of destruction: the obliteration of wealth in the financial markets and the destruction of property in the United Kingdom. This destruction involves different actors, objects, temporalities, and spatial scales. The looting by youths in the UK had a short-term temporality and has been territorially contained to one nation. But this destructive violence had a profound affective impact because of its power to temporarily wrest the streets from the control of the state and because it can be immediately represented, visually and live, on countless screens. The corporate media promptly mobilised these images of burning shops, burning police cars, or wounded passersby to scare and enrage the ‘normal citizens’ and modulate their attachment to state authority through the image of looters in hoodies.

But the media are simultaneously covering another form of looting, one that operates on a much vaster temporal and spatial scale and creates much deeper forms of social and material devastation. The sacking by the global financial elites of the collective wealth of myriad countries, from the United States to Greece, has been going on for much longer and is ruining not just property but millions of lives. As Paul Krugman has repeatedly argued, the main outcome of this neoliberal devastation is pain. The debris that testifies to this pain is there for anyone to see: dozens of millions of jobs destroyed, millions of homes foreclosed, public services reduced or shut down in hospitals, schools, and public libraries, pension plans evaporated, social security eroded. In Europe, the UK has led the way in this hugely destructive transfer of wealth away from the commons. Yet this devastation and those responsible for it are harder to represent visually in the 20 second-clips that the media relies on. Being scattered in countless places, this is destruction that the corporate media tends to hide from view or to dilute politically as the product of those ever-uncontrollable and faceless market forces.

Yet this capitalist sacking can and should be represented. And we should start calling it by what it is: looting, as many people in the critical blogosphere are. This capitalist sacking has accelerated since the 2008 financial crisis and has become a destructive appropriation, supported with the repressive power of the state and in most cases against the will of the majorities, of what used to belong in the public domain. Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, the UK, the US are all variations of the same story.

The looters in hoodies are being promptly punished by the state. With over 1,000 arrests, the British courts are at capacity and overwhelmed. The capitalist looters in Armani suits, in contrast, destroy with impunity. They know they are above the law because they are the planetary elite, what we should probably call (resurrecting an old-fashioned but also crystal-clear political concept) the global oligarchy of the 21st century. Oligarchs are, after all, actors so wealthy and powerful that they control the state and do as they please with impunity, even if they act against of the will of the majority of the population. Our oligarchs devastated the world economy in 2008-2009 yet landed on their feet with grins on their faces, knowing all too well that this destruction not only left them unscathed but actually made their wealth thrive. They continue calling the shots and preaching the wonders of free markets, as if millions of homes had not been already devastated under their watch. Obama, after all, put the US economy in charge of the same men from Wall Street (Larry Summers, for instance) who deregulated the financial markets and led them to their collapse (as the film The Inside Job crudely shows). These professional looters in suits do not have to fear being called ‘thugs’ by the British prime minister, despite bullying whole nations into destroying their social safety nets and shutting down hospitals or daycare centers. Like zombies insensitive to the ruins piling up around them, they keep preaching their old credo as we enter yet more destructive economic turbulence of their creation.

It’s about time to stop calling the devastation created by capitalism ‘creative destruction’, as progressive thinkers like David Harvey often do. Popularised by Joseph Schumpeter in the 1940s, the term ‘creative destruction’ appropriates the negativity of Marx’s view of capitalist destruction in The Communist Manifesto and rephrases it as creative, thereby depoliticising it. Through a subtle yet decisive ideological sleight of hand, capitalist destruction is redefined as innovative, positive, desirable: an unavoidable outcome of its thriving dynamism. It is therefore not surprising that neoliberal economists and corporate apologists often celebrate the ‘creative destruction’ of capitalism, for in this usage the positive element, creation, subsumes and neutralises the negativity of destruction. But there is nothing creative in capitalist destruction for those who live amid its rubble. Capitalism certainly produces enormous amounts of goods, wealth, and technological innovation, but as part of a destructive system of production that, as Ann Stoler would put it, ruins the lives of millions. Michael Moore’s Capitalism: A Love Story can be seen in this regard as a gripping journey through the experience of people whose lives have been destroyed by unregulated financial capitalism in the United States.

The destructive production created by the capitalist global order takes us back to the destruction of property by kids in hoodies on the British streets. In an interview on BBC that has gone viral, Darcus Howe forcefully articulated (to the horror of the anchorwoman) that in the UK this devastation is profoundly racialised and supported by police brutality. This, he explained (while the anchorwoman was trying to shut him down), is the affective terrain that created the nihilistic rage behind the riots. Many analysts have emphasised the obvious: that riots are complex social phenomena that respond to multiple factors and determinations. But the action of looters in hoodies is not disentangled from the capitalist looting by people in suits that has eroded social services and opportunities in these youths’ neighborhoods and is taking, again, the global economy to the edge of the abyss.

The capitalist looters, needless to say, don’t want us to connect the dots. A certain Andrew Roberts on The Daily Beast wrote, with indignation, a piece on the riots entitled ‘Stop blaming the wealthy’. He proposes, instead, to blame the poor. The core reason for the riots, he says, is the welfare state and the ‘entitlements’ that make poor people lazy. This ‘uprising’, he tells us, is that of ‘the non-working, anti-working, would-do-anything-sooner-than-work class’. The cheerleaders of corporate power hate it when people point their fingers at the oligarchs. It’s much easier to point to youths in hoodies and call them ‘scum’.

There is nothing in the UK riots to feel good about, particularly when lives have been lost. As usual, only the right benefits from them. This is what happened in France after the insurrections at the Paris working-class suburbs in 2005. As Minister of the Interior, Sarkozy demonised the rioters as ‘rabble’ and became the champion of a scared middle-class. A few years later, as French president he proceeded to hand the government over to professional looters (the crème of the national oligarchy) committed to sacking and eroding the national pension plan despite massive opposition on the streets. The bogeyman of the hooded kids setting cars on fire served the capitalist looters well.

There is much to worry about in what is to come, particularly because of the rise in popularity of fascist views of the looters that call for state and vigilante violence (calling, for instance, for their execution). But the riots were also dramatic ruptures in the texture of the neoliberal order, which reveal with brutality that there is nothing orderly and calm behind the façade of the everyday consumerism most of these youths feel excluded from. As Paul Lewis and James Harkin from the Guardian put it after talking with several rioters, capturing the rudimentary anti-systemic politics of their actions: ‘This is unadulterated, indigenous anger and ennui. It’s a provocation, a test of will and a hamfisted two-finger salute to the authorities.’

In the 1980s and 1990s, as Naomi Klein has shown in The Shock Doctrine, Latin America was the terrain on which the global elites first experimented with the extremely unregulated capitalism that is now wreaking havoc in the US and Europe. This is why many people in and from Latin America, myself included, are following the news coming from Europe and North America as déjà vu. Privatisations, brutal spending cuts, default, riots? Been there done that.

By the early 2000s, the social devastation created by the capitalist sacking of Latin America was so dramatic that it led to several popular insurrections, an anti-neoliberal backlash, and a wave of democratically-elected left and centre-left governments that, despite their differences, have partly reconstructed the welfare state, put limits to the reign of corporate power and the IMF, and set on a course of sustained economic growth. And many of those responsible for the capitalist looting of the 1990s had to flee the continent. Most found a safe haven on Ivy League campuses in the United States.

In 2000-2001, I had a first-hand, often surreal experience with some of these former looters in exile when I was a postdoc at Harvard and kept running into them on campus. Most of these former officials could simply not live in their home countries anymore because most people saw them as persona non-grata responsible for widespread social destruction. I once attended a talk, for instance, that included in the audience the former President of Ecuador Jamil Mahuad (toppled by an insurrection in January 2000), his former finance minister, and a former minister of Menem’s cabinet in Argentina. They were all Harvard fellows. But I was still not fully prepared to stomach a speech by the then president of Harvard, Larry Summers, who had just deregulated US financial markets under Clinton. In the spring of 2000, Summers praised at a public event the recent nomination of Domingo Cavallo as finance minister of Argentina for a second time. He condescendingly argued that Cavallo’s Harvard education guaranteed the success of his tenure in that distant South American country, failing to mention that the then rapidly-worsening situation in Argentina was Cavallo’s own making (when he engineered the neoliberal sacking of the commons as Menem’s finance minister). A year and a half later, Cavallo’s policies and his freezing of all bank accounts to protect the banks triggered a popular insurrection. The night of December 19, 2001, a crowd of thousands surrounded the high-rise building in Buenos Aires where Cavallo lived, hitting pots and pans and angrily demanding his resignation, which took place that same night. The following day the Argentinean president followed suit. Cavallo fled the country to the United States and joined the other elite Latin American expats at Harvard, which always opens its arms to looters of all stripes, as long as they don’t wear hoodies.

The cases of Latin America and also of Iceland, where sustained popular protests have began undoing the capitalist looting that made its economy implode just a couple of years ago, simply confirm that there is nothing natural or inevitable in the devastation that is now descending, again, upon the northern hemisphere. And the former Latin American financial oligarchs now living in exile in the Ivy League remind us that, despite their immense power, what these looters in business suits fear is not the looters in hoodies. They fear resonant multitudes on the streets rupturing the neoliberal order not through random destruction but through the collective and assertive defense of the commons.

Originally published on Critical Legal Thinking. LIcensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 3.0 license.

Image top: Tobias Leeger.

Gaston Gordillo blogs at Space and Politics.

{jathumbnailoff}