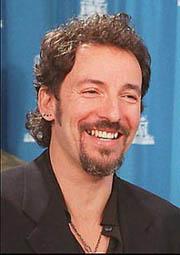

Bruce: back on the loose

Derided by musical snobs, misguided in lending support to John Kerry's Presidential campaign, Bruce Springsteen remains one the great chroniclers of American life. And he's on tour again. By Harry Browne.

Ten years ago it looked like Bruce Springsteen was ready to grow old gracefully. There he was, in his mid-40s, touring with The Ghost of Tom Joad, his receding hair tied back and his acoustic guitar slung below his harmonica, and he sang quiet songs about lives of desperation.

But the man clearly had ants in his pants. A few years later he was back with the E Street Band, and by 2002 he was pumping out a new generation of rock anthems from The Rising, boyishly hanging upside-down from the microphone stand – even his hairline was miraculously restored. Reclaiming his place in the rock 'n' roll pantheon, he was a big enough star to spearhead the drive for John Kerry's election, though not a big enough star to win it.

To complicate matters, now he's here again, touring with that acoustic guitar, showcasing a new album, Devils & Dust, that was mostly written back in the mid-to-late 1990s. Pinning a coherent chronological "arc" on Springsteen's career, a simple enough act during that quiet Tom Joad tour, gets more awkward.

To hear him tell it himself, he's still just working out the dual facets of his musical character. He was signed in the early 1970s as another "guy with a guitar", a folkie – spotted by Columbia Records' John Hammond, discoverer of Bob Dylan and Billie Holiday. At the time Springsteen might find himself fronting a New Jersey bar-band one night, then strumming solo in a Greenwich Village coffee-house the next.

Back then he was saddled, like too many of his contemporaries, with the burden of being the "new Dylan" – ie his songs had a lot of words and they weren't always easy to figure out. In some ways, Springsteen continues to operate in Dylan's venerable shadow, and the new album contains some of the most explicit echoes of that master.

Back then he was saddled, like too many of his contemporaries, with the burden of being the "new Dylan" – ie his songs had a lot of words and they weren't always easy to figure out. In some ways, Springsteen continues to operate in Dylan's venerable shadow, and the new album contains some of the most explicit echoes of that master.

But there was and is a huge difference between them as artists, and perhaps it goes to the heart of why Springsteen remains under-rated by musical sophisticates. The Jersey Boy's songwriting and performing persona are emotionally direct and uncynical – which Dylan's sure ain't. There's something artier about Bob's air of mystery than Bruce's air of approval-seeking. Folk musician Elliot Murphy puts it well: "While Dylan has done his damnedest to keep us from knowing him at all and in most ways succeeded, Bruce Springsteen only wanted us to get to know him better, in a folksy way, and to understand why he had to write these songs."

If the overall shape of Springsteen's career now looks circular, the songs and their writer have nonetheless moved (simplifying slightly) through a few clear stages. There's the verbosity and angsty exuberance of the early 1970s, when his voice was that of a greaser who shifted awkwardly between the city and the shore, looking for love and fun. This culminates and begins to shift in the magnificence of 1975's Born to Run, when the sound turns less jazzy, more ponderous but often explosively rocking. The writing starts to get pared down, more self-conscious, and the unfair accusation that he's over-reliant on cars as his lyrical "vehicle" gets its ammunition. However, many songs, especially on The River, are beautifully considered reflections on the twists in life's journey, with or without wheels.

This period, up to the mid-1980s, is "love him or hate him" time – though some people who hated the rock star "Boss" loved the strange, uncorporate exercise that was 1982's darkly acoustic Nebraska. Ironically, in the minds of many "true fans" Springsteen's commercial apogee was his artistic nadir: 1984's Born in the USA turned him into a household name and unlikely jingo, but nowadays even people who jumped on the bandwagon at that time disdain the album as a hit-seeking missile aimed straight at a middle-of-the-road audience.

Then things quickly quieted down. The next decade's material, both the songs released at the time and the ones that turned up later, tended toward autobiography. Tunnel of Love (1987) can easily be heard as a chronicle of his unhappy marriage to model/actress Julianne Phillips. (We tried to warn him: even the old fans who liked Born in the USA hated that Hollywood marriage.) Then he got it together with backing singer Patti Scialfa, much nearer his own age, background and attractiveness-quotient, and 1992's Human Touch and Lucky Town partly deal with the transition to happiness. The E Street Band had been jettisoned.

Bruce seemed content even with the relative obscurity these records achieved. On Lucky Town's "Better Days" he critiques his earlier success as a "working-class" rock star:

Well I took a piss at fortune's sweet kiss

It's like eatin' caviar and dirt

It's a sad funny ending to find yourself pretending

A rich man in a poor man's shirt

And that, it seemed, might make his epitaph.

But if Springsteen no longer felt comfortable donning poor men's clothes, he remained interested in them (playing a lot of benefit gigs) and their stories. His folkiest album, The Ghost of Tom Joad (1995), was based on meticulous research into diverse subjects: the Vietnamese "boat people" who settled on the Gulf of Mexico coast; the drug trade across the Mexican border; the decline of heavy industry in Ohio. The album contained some of his most specific and spare writing, and if it wasn't exactly easy listening it was certainly a pointed jab at Clinton-era complacency. "Shelter line stretchin' round the corner / Welcome to the new world order", he sang in the title track. And he didn't spare his own history as poet laureate of lovable losers who can drive their way to freedom: "The highway is alive tonight / But nobody's kiddin' nobody about where it goes".

And that, in a sense, is where Devils & Dust comes in. Except that, of course, 11 September, 2001, "changed everything". The social geography of the World Trade Centre atrocity was precisely his territory, and he famously began to hear about victims (firefighters, commodity traders) having 'Thunder Road' or 'The River' played at their memorial services. For decades in America the words "working class" were hardly spoken except in reference to Springsteen – white Americans, except the very rich and very poor, are always "middle class" – but when they were revived to describe the "heroes" of 9/11, it seemed natural that Bruce would re-emerge to chronicle them.

The Rising (2002) did so with extraordinary energy and integrity. He wrote and sang transcendently about firemen, but also questioningly about heroism, and in 'Paradise' he puts himself, uncondemning, in the mind of a suicide bomber. The album ends with 'My City of Ruins', an account of urban poverty and a call to "Rise up!" that had been conspicuously absent from Tom Joad. However, The Rising, despite the evident wisdom about Ireland and the Irish that Springsteen displayed in his brilliantly begrudging, self-mocking speech about U2 at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame this year, didn't have much to do with rebellion.

The Irish-Dutch-Italian Springsteen, often in the past mistaken for a nice Jewish boy who'd changed the spelling of his name, was singing about Christian, and indeed Marian, redemption. In fact, such was the overt spirituality of The Rising that it was slightly surprising that he decided last year to involve himself so temporally in the Kerry campaign. Like many liberals, he mistook Kerry's laboured, militarist run at the White House for a righteous crusade, and got stuck in immodestly. The election, he told rallies, was about the same things his songs are about: "who we are, what we stand for, what we fight for now".

His anti-war statements were almost as cautious as Kerry's, and the title track from the new album – written in 2003 – fails artistically and politically. 'Devils & Dust' is narrated by a US soldier in Iraq, but apart from a dream of "blood and stone" and "mud and bone" it lacks hard specificity and any wider sympathy for the war's victims. Instead it relies on an agonised liberal's vague Q&A:

What if what you do to survive

Kills the things you love

Fear's a powerful thing

It can turn your heart black you can trust…

Between growled lyrics like that and its bland tunelessness, the song is among the best exhibits Springsteen-haters have had in years. Luckily, however, the rest of the album is much, much better. In it, the socially astute storytelling of Tom Joad has been joined by the intense spirituality of The Rising and some of the domestic solace of Lucky Town. Moreover, Springsteen has evidently convinced himself that wearing the "poor man's shirt" is a legitimate literary exercise, and he enters the lives and voices of struggling black and Latino characters more fully than ever.

Indeed, the critics who see the "family values" and Christianity on Devils & Dust as some form of pandering to Bush's America are showing their ignorance of the immigrant and minority communities where these are the foundations of survival and transcendence, and Dubya is anathema. In music as well as lyrics, Springsteen here is particularly exploring country ('Long Time Comin''), blues ('All I'm Thinkin' About') and gospel ('Jesus Was an Only Son'), genres which have never been short of devils and dust.

Sure, there are some hokey claims on rootsy authenticity going on here. But if, as detractors and snobs often insist, Bruce Springsteen is some sort of put-on, it's the most sustained and dedicated fakery in the history of popular music. As a friend told Village: "Most artists who become successful put together some way of presenting themselves to the public which combines some part of who they are and who they wish to be. In the case of Bruce, I know how clearly he sees his mission as an artist and how undistracted he is by the trivial.

"He is simply a person with no real cynicism about him."

Bruce Springsteen plays the Point Theatre in Dublin on Tuesday 24 May