Benedict XVI: A Year Later - Former friends

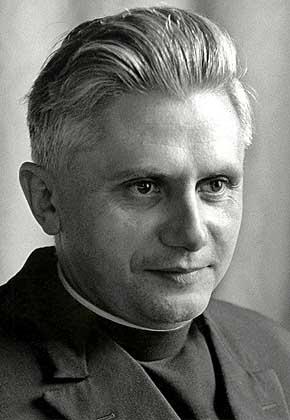

Hans Kung and Joseph Ratzinger were colleagues and friends at the Second Vatican Council in the 1960's. Both theologians, both liberal. But Kung was later "silenced" by the Church and Ratzinger became the Church "enforcer". Now as Pope Benedict XVI, Joseph Ratzinger again has befriended his former friend. Hans Kung writes about an extraordinary meeting.

I have never disguised the fact that I was tremendously disappointed when the most recent conclave selected as pope Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which used to be called the Inquisition.

Nonetheless Benedict XVI deserved to be given a chance. So, despite all the criticism, I was initially restrained in my judgment and, as I had planned years before, I asked the new pope for a personal conversation.

I had waited in vain for 27 long years for a reply to my letters to John Paul II, so it is understandable that I was surprised and delighted when, after writing to Benedict on 30 May 2005, I received a friendly reply as early as June 15: the new pope was ready for a "brotherly conversation" with me.

That conversation took place on 24 September in the papal summer palace, Castel Gondolfo, and lasted a full four hours. For many people throughout the world it was a sign of hope that, although we had gone different ways and adopted different standpoints, we continued to have something decisive in common: we are both Christians, we both serve the same church and, despite all the controversies, we respect one another.

We didn't cover up our differences. I wanted to present the concerns of large and important parts of our Catholic church. With my letter I had enclosed my "Open Letter to the Cardinals", published before the conclave, which gave my view of the future course of the church and a comprehensive programme of reform. But there seemed to be no sense in devoting this personal conversation to the details of individual reforms within the church about which Benedict and I had long had completely different views.

Generally speaking, I was hoping not for another media pope, but rather for a pastoral pope sympathetic to ecumenism. And there were signs of hope here. This pope is a more tranquil, thoughtful scholar, given to reflection, who is not constantly engaged in great public appearances and has reduced the number of both papal visits and public audiences in Rome.

He is a supreme pastor who proceeds more in slow, small steps, who needs time and who prefers to use small changes to set greater ones in motion. Short periods of free discussion at the latest Synod of Bishops and his invitation to the cardinals to express their opinions freely have offered at least a beginning of collegiality.

Benedict is, in short, a conservative who is still open in some respects. At any rate he is not an utterly rigid conservative, and he might still give the world some surprises, as he did in his readiness to have a conversation with me.

I know that many knowledgeable observers of this pontificate are sceptical, asking "can a leopard change its spots?" I remain a realist, but don't want to give up hope. Things rarely turn out as well as one hopes, but they aren't always as bad as one fears.

So where is Benedict XVI taking the Catholic church? The question is one of global political significance, not only to Catholics and other Christians but also to adherents of other faiths and secular men and women in politics, business and the academic world.

After all, with more than a billion active, passive or nominal members, the Catholic church is the most important religious multinational body in the world, with an internal organisation tight enough to make it an efficient global player despite all its weaknesses. Heads of states and governments from all around the world came to St. Peter's Square for John Paul's funeral, and not solely out of devotion.

Quite independent of his person, the pope is a spiritual world power and for many people, young and old, is a credible moral figure with whom they identify.

The future direction of the Catholic church is therefore of global importance, and it was global issues that Benedict and I discussed during our conversation in Castel Gondolfo. In particular we talked about three problem areas in which I hope for some progress in the new papacy.

First was the relationship between the Christian faith and science, indeed secular disciplines generally. The rationality of the faith was always important to Ratzinger the theologian, and in the joint press release after our meeting the pope "endorsed Professor Kung's concern to revive the dialogue between faith and science and to show how in its rational and necessary nature the question of God can be brought to bear on scientific thought".

But I do not know the scope of this endorsement. Is it limited to physical, biological and theological questions of the origin of the cosmos, life and humankind, or could it be extended in a rational conversation to further questions of biology and medicine, such as embryonic research, birth control and artificial insemination?

We also discussed the dialogue of religions. Benedict has on various occasions spoken out against the idea of a "clash of civilisations". He too is convinced that there will be no peace among the nations without peace among the religions, and no peace among the religions without dialogue between them. Thus in the press release I could express my "approval of the pope's concern for dialogue between the religions and encounter with the various social groups of the modern world".

Here too, however, I was left with a question: given all the defects of Christianity and the positive points of other faiths, will this pope be able to combine his conviction of the truth of his own faith with respect for the truth of other faiths?

Third and finally we talked about the importance of a shared human ethic. Benedict understands that "the Global Ethic Project is by no means an intellectual construction" but rather brings to light "the moral values in which the great religions of the world converge, for all their differences. By their convincing meaningfulness these religions can prove to be valid criteria for secular reason also."

It is beyond question an important reinforcement for the Global Ethic Project that the pope sees in a positive light my concern over many years "to contribute to a renewed recognition of the essential moral values of humankind in the dialogue of religions and in the encounter with secular reason", and that furthermore he also emphasises that "commitment to a renewed awareness of the values which support human life was also an essential concern of his pontificate".

Again, however, we must ask a question: at the next meeting of religious leaders in Assisi or elsewhere, will there be only prayer, or will it prove possible also to emphasise the shared ethical standards of the religions?

Looking forward

Of course I had no illusions of true accord between Benedict and myself, nor have I any now. By agreement we concentrated on questions of church "foreign policy", touching only fleetingly on the controversial questions of church "domestic policy" which are being vigorously argued in the church community.

Benedict certainly knows better than to expect me to keep quiet about my concerns for reform in the future, concerns which are not solely my own. Avoiding the church's "domestic policy" may make for a more congenial conversation, but the Catholic church is in so serious a crisis – crisis rooted in those "domestic issues" – that no pope could reasonably expect to sidestep those issues indefinitely.

In my "Open Letter to the Cardinals" I drew on the New Testament, the great Catholic tradition and the Second Vatican Council of 1962-1965 in order to answer the question of what kind of pope the Catholic church needed. A year has passed, but whether Benedict is that man remains undetermined.

Now that he has settled into his role as pope, Benedict must choose between a further retreat into the pre-modern, pre-Reformation universe of the Middle Ages or a forward-looking strategy that will move the church into the postmodern universe which the rest of the world has long since entered.

Benedict might decide to retreat, but I doubt that he will. He might choose to stay where he is, but to simply celebrate the papacy instead of helping the church in its need would in fact constitute a step backward. Or he might decide to go forward, and that is what I – and countless people inside and outside the Catholic church – hope for from him.

The pope realises that the church is in a serious situation. John Paul failed to win many converts to his rigorous views, especially concerning sexual and marital morality, despite all his speeches and travels. Those views were rejected by the overwhelming majority of Catholics as well as national parliaments, even in his native Poland. All his encyclicals and catechisms, all his decrees and disciplinary sanctions, all the Vatican's pressures, whether open or concealed, on his opponents in fact achieved almost nothing.

Perhaps Benedict has also been able to perceive from the Vatican that his campaign for the "re-evangelisation of Europe" has fomented fears of the spiritual imperialism of Rome and tacitly contributed to the rejection of any mention of God or even of Christianity as a cultural factor in the preamble to the European Constitution.

Papal mass rallies, however well organised and effective in drawing the media, cannot conceal the fact that, behind its triumphal façade, things do not look good for the church.

There is a deep gulf between what the hierarchy commands and what church members in fact believe, a gulf reflected in how they live. Church attendance is in decline, as are church weddings. The practice of confession has disappeared in most Western countries, and the acceptance of church dogmas is decreasing. The ranks of the priesthood are thinning and there are few replacements available, in part because clerical credibility has been severely shaken by the paedophilia scandals that have spread from the United States and Ireland to Austria and Poland.

As long as the pope tries to achieve the absolutist primacy of Roman rule, he will have the majority of Christians and the world public against him. Only if he embraces the model of John XXIII and attempts to practice a pastoral primacy of service, renewed in the light of the gospel and committed to freedom, will he be a guarantor of freedom and openness in the church and be able to serve the world as a moral compass.

If Benedict XVI could lead the church out of this crisis of confidence and hope, he would lead what Karl Rahner called the "winter church" into a new spring. He knows the Curia and episcopate better than anyone else, and unlike his predecessor he is a good administrator and a distinguished scholar. One of his rivals in the conclave told me that, if he wanted to, Benedict could carry through reforms which a more progressive pope would not find so easy.

So many people inside and outside the Catholic church are expecting the breakup of a quarter-century's logjam of reforms. They want the church's long-standing structural problems to be discussed openly and they want solutions to be found, whether by the new pope personally, by the Synod of Bishops or even by a Third Vatican Council.

© 2006 Hans Kung

Ratzinger and Kung

Joseph Ratzinger got his first theological professorship because of the direct intervention of Hans Kung at Tubingen university, Germany, in 1966. Kung had been impressed by Ratzinger's performance during the Second Vatican Council and particularly in his role as adviser to Cardinal Frings of Cologne, who made a celebrated assault on the then Vatican "enforcer" Cardinal Octavanni, on 8 November 1963. Frings had told a cheering Vatic II audience of bishops and cardinals: "The Hole Office does not fit the needs of our time. It does great harm to the faithful and is the cause of scandal throughout the world". Ratzinger was believed to have been the author of that speech delivered by the elderly, frail, almost blind cardinal of Cologne.

In 1969 Kung and Ratzinger were co-signatories of what was known as the Nijmengen Statement which declared: "Any form of inquisition, however subtle, not only harms the development of sound theology, it also causes irreparable damage to the credibility of the [Roman] church … We expect our freedom to be respected whenever we pronounce or publish."

Later that same year it seems Joseph Ratzinger's world outlook began to change (although he has repeatedly asserted his views did not change). He was a "target" of the student protests at Tubingen university, his microphone was snatched from him, his offices and lectures were disrupted. He said: "The abuse of faith has to be resisted."

He did, however, later give support to a book Hans Kung wrote attacking the idea of papal infallibility, but subsequently became the Vatican's "enforcer" as head of the Congregation for Doctrine and Faith. Kung once wrote of him: "He sold his soul for power."

Kung is the world's best-known theologian. A Swiss national, living in Germany, the Vatican withdrew his church authority to teach theology in 1979.

He was hugely critical of the pontificate of Pope John Paul II. He wrote: "In my view, Karol Wojtyla is not the greatest, but certainly the most contradictory, pope of the 20th century. A pope of many great gifts and many wrong decisions!

"Outwardly, John Paul II supports human rights, while inwardly withholding them from bishops, theologians and especially women … The great worshiper of the Virgin Mary preaches a noble concept of womanhood, but at the same time forbids women from practicing birth control and bars them from ordination…

By propagating the traditional image of the celibate male priest, Karol Wojtyla bears the principal responsibility for the catastrophic dearth of priests, the collapse of spiritual welfare in many countries, and the many pedophilia scandals the church is no longer able to cover up..."

On the election of Joseph Ratzinger as the new pope, Hans Kung wrote this was "a major disappointment".