Beating them at their own game

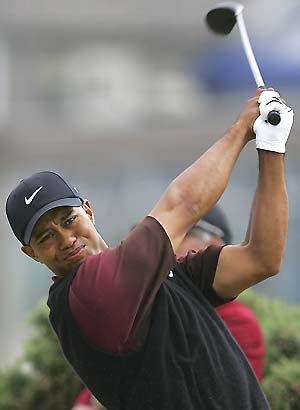

How Tiger Woods overcame the institutional racism of US golf to become the greatest player of his generation. By David Walsh.

There are a few things we should know about Tiger Woods. On his first day at school in Cypress, the town in southern California where he was born, a group of older white boys tied him to a tree and spray-painted the word "nigger" on him. The teacher didn't do much; just told the young Woods to go home and get on with it. The Woods' were one of a handful of black families in Cypress.

When he played golf, Woods encountered the same racism that for so long had been part of the game's DNA. Until May 1961, the constitution of the Professional Golfers' Association of America explicitly limited membership to "Professional Golfers of the Caucasian Race". Tiger Woods began playing the game soon after he learned to walk. At age four, he appeared on the Mike Douglas Show to demonstrate how extraordinarily well he played the game. By the time he was 14, the worldwide sports management agency IMG was hot on his trail.

So you imagine great talent overwhelmed prejudice and that golf clubs couldn't wait to welcome this potential phenomenon? It wasn't quite like that. Once asked by a group of kids what it was like growing up, Woods said, "It was great, but there were times when I wasn't allowed to play golf." Later, he recalled precisely what it had been like.

"At the Navy golf course [Tiger's father, the late Earl Woods was a military man], where I grew up playing, there's an age limit – at military golf courses it was 10 and over. But for some reason, all the white kids were allowed to play who were 10 and under, though I wasn't.

"I had people who were older – and I don't know if they were servicemen or retired or active or guests... I don't know who they were – use the N word with me numerous times. I was there pitching, just pitching at a little chipping green. And they wanted to pitch, so they would yell at me and I'd have to go to the putting green. So I'd go to the putting and I'd get yelled at over on the putting green.

"I'd go back to the chipping green, then get yelled at on the chipping green. These are things that obviously hardened me a little bit and made me realise that golf was not like basketball or football at the time. It was different, under different rules. Even travelling the country as a kid, I wasn't allowed to go certain pro shops or certain clubhouses to change shoes where all the other kids were allowed to. Being black is just looked at differently."

Even in the moment of his first great victory as a professional player, the 1997 Masters at Augusta National, Woods was reminded of who he was and where he was perceived to have come from. At a time on that Sunday afternoon when the 21-year-old Woods was on his way to setting a new record for the lowest winning score in the Masters, his fellow professional Fuzzy Zoeller was asked by a television reporter for his take on golf's new star. "That little boy," said Zoeller, "is driving well and he's putting well. He's doing everything it takes to win. So, you know what you guys do when he gets in here? You pat him on the back and say congratulations and enjoy it and tell him not to serve fried chicken next year. Got it?"

Zoeller then smiled, snapped his fingers and walked away. But like a man remembering something he had meant to say, he turned back, faced the camera and said: "Or collard greens or whatever the hell they serve."

The comments about fried chicken and collard greens related to the following year's Champions Dinner at which Woods, as the previous year's winner, would be allowed to chose the menu. The laugh was supposed to be in the irony of Woods serving up a supposedly black man's dinner to a group of privileged white folks. Zoeller was then an outgoing and, at times, outrageously funny man, but his attempted joke was not funny and rebounded on the would-be joker.

Perhaps deservedly, Zoeller was hung out to dry and Woods, who could have saved him, let him suffer. He didn't publicly criticise Zoeller – everyone else was doing that so there was so need. But when the baiting of the then 45-year-old pro reached a frenzy, one wondered if Woods would say a conciliatory word and end it. His silence remained stony. No one takes liberties with Woods, on or off the course.

To fully understand the man, one must know about the diversity of his racial background. Earl Woods was African-American but Tida, his mum, is Thai. While Earl was teacher and mentor to the young golfer, Tida instilled many of the values that now make Woods the man he is. He was raised in what he has called "the Asian tradition".

"A Far Eastern culture," he said, "as anyone who has experienced it knows, is very strict. So you have responsibilities. You had to do what you had to do if you were delegated a certain responsibility, and you never did anything to bring dishonour to your family. You can't disrespect anybody who's older than you, because if you do you've disgraced your entire family. That's kind of how I was raised, and from what I've seen it's a different philosophy from other cultures that I've been exposed to in America that are not Asian.

"If I didn't say 'Yes, sir', 'Yes, ma'am', 'Thank you, ma'am', 'Thank you, sir', I'd be smacked in a heartbeat, right on my butt. That's just how it was."

"If I didn't say 'Yes, sir', 'Yes, ma'am', 'Thank you, ma'am', 'Thank you, sir', I'd be smacked in a heartbeat, right on my butt. That's just how it was."

A strict but loving upbringing taught Woods how to behave; formidable athletic gifts have enabled him to be the greatest player of this and perhaps every other generation; and a huge natural intelligence has helped him to deal with trappings of super-stardom. To be in his presence for half an hour is to realise that he may be the brightest sportsman we have ever seen.

For he learned sooner than anyone could have believed possible that though he could never betray his black background, neither could he allow himself to be pigeonholed into the role as leader and saviour of one community. When he first played the Masters, he was 19 years of age and still an amateur. But he was old enough to know that August National was as much a symbol of the Old South as the plantation farm on which the course was built.

So at the end of his third round, the 19-year-old Woods saw Lee Elder in the gallery around the 18th green and after putting out, Woods went over to Elder who in 1975 had become the first black to earn an invitation to play in the Masters. It was right that the teenage Woods should have shown his respect to Elder because without black players such as Elder, Charlie Sifford, Pete Brown and Jim Thorpe, the path into an elitist sport would have been even more difficult for Woods.

But such is Woods' talent and his understanding of what he can achieve that he was never going to settle for being solely an advocate for one group of people. He would have known that when he sunk that final putt to win his first major – and by a record margin at that – the distinguished and predominantly white members of Augusta National almost raised the roof with the velocity of their roar. When you can affect so many, why would you settle for so few?

"I will be a leader for everybody," he once said. "Not just one group. I don't want to limit myself, and I won't be pigeonholed. I just feel like I can do more than be a leader strictly to blacks or strictly to Asians. I'm not going to limit myself to just one race, one religion or one sex. Any effort I'm involved with is going to be about everybody."

To come from where he has come and to arrive at this point... so far, it's been an impressive journey.