Austerity economics, recession, and the gender gap

The effects of austerity economics are devastating – moreover, they are designed to target those who can bear it least. Like its predecessor, the new Irish government persists in using neoliberal policies to solve a problem created by neoliberal policies. Adam Larragy highlights how the impact of this approach has not been gender neutral.

Yvette Cooper, the British Labour Party’s Shadow Home Secretary, has recently argued that, for the first time, the next generation of British women may have fewer opportunities and less equality than previous generations of British women. The British Labour Party has – admittedly somewhat belatedly - taken a strong stand against the new Liberal/Conservative government’s proposed cuts in child benefit, child tax credits, and childcare tax credits. While the British people, and British women in particular, have only begun to experience austerity economics, the Fianna Fáil/Green government began cutting social expenditure two years ago even as the Brown government was introducing extraordinary measures to shore up the British economy.

The Irish economy has suffered a far graver recession than either its neighbour or its peers, with a contraction in GNP of nearly a fifth and spiralling unemployment. The impact of both increasing unemployment and cuts in government expenditure has not been gender-neutral; women have borne the greatest burden of expenditure cuts while recent unemployment and IMF structural reforms may affect women in a far greater way than hitherto. Sadly, the impact of the recession on women has not featured in Irish debates as much as might be expected, despite the tireless work of organisations such as the National Women’s Council of Ireland (NWCI), and indeed questions of gender equality are either relegated to the side lines or sneered at in sections of the media.

It is perhaps indicative of the tone and tenor of public debate in Ireland that a proposal to reduce income tax to incentivise second earners to join the labour force contained in a recent IMF Staff Position Note sparked a considerable outcry. The actual suggestion contained in the Position Note stated that given the ‘implicit tax on the gross income of a second earner tops 70 percent when including social security contribution, benefits loss, and the cost of child care’ some form of tax incentive or increased child-care support would increase labour participation. The resulting public debate on the so-called ‘man tax’ as one wit called it, obscured rather than enlightened and revealed a number of worrying trends in the public discussion - such as it is - of the contrasting effects of the economic crisis on men and women in Ireland. The discussion was based on supposition and anecdote, and there was an attitude that questions of gender equality could take a back seat during the recession. Moreover, there was considerable anger expressed at supposed preferential treatment given to women. That the IMF proposal applied to second earners regardless of gender barely entered the debate.

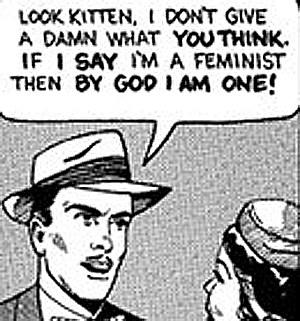

One of the difficulties confronting those who seek to achieve greater gender equality is the sometimes hysterical reaction of mainly middle-class, middle-aged men in regard to questions of gender equality and women’s rights

The economic and financial crisis has affected women and men very differently due to the numerical predominance of one gender in certain sectors of the economy. In sectors such as construction and related industries, men have suffered most. According to the Quarterly National Household Survey in the third quarter of 2010, employment in construction has fallen 58% since its height in 2007. This has forced many skilled workers in this sector, the vast majority of them men, into unemployment or forced emigration. However, the burden of public expenditure cuts has fallen more heavily on women: they are more likely than men to be employed in the public service (in health and education by a ratio of 3:1); more likely than men to take the role of primary care-giver in a household (by a ratio of 98:2); more likely than men to be working in the home (by a ratio of over 99:1); and more likely than men to lead a single-parent household (by a ratio of 9:1). As such, the cumulative cuts in the Widow’s Pension, One-Parent Family Payment and the Carer’s Allowance by nearly 10%, the cuts in Child Benefit by 8.5%, cuts in services and cuts in public sector pay have all affected women more heavily than men. Perhaps the most cynical manifestation of this tendency was Mary Harney’s initial decision to refuse to introduce the HPV vaccine on the grounds of cost.

As the economic crisis enters a new stage, with further expenditure cuts and public sector redundancies pencilled in for the next five years by the new government, women in the labour market may begin to bear an even greater burden than hitherto. While the massive loss of jobs in construction seems to have hit its trough, reduced domestic demand - induced through increased VAT, the introduction of the Universal Social Charge, and the impact of spending cuts - is likely to produce further job losses in the retail and hospitality sector, in which women are more represented than men. Furthermore, the cuts in public service numbers are likely to impact women more than men, despite the new government somewhat implausibly pledging to remove workers in administrative posts - in which the male/female split is nearly 50:50 – rather than frontline posts. The welfare system is not designed to facilitate those on part-time contracts; again the vast majority (74%) of whom are women. The review of Registered Employment Agreements (REA) and Employment Regulation Orders (ERO) – part of the IMF/EU programme - may lead to significant wage reductions in traditionally female-dominated industries such as hairdressing, contract cleaning and catering.

Yet despite the efforts of organisations such as the NWCI, the disproportionate effects of the financial and economic crisis on women remains on the sidelines of the public debate on fiscal, banking, labour market and social policy. The NWCI has pointed out that households headed by women experience greater poverty, with 17% living below the poverty line while 36% of one parent families were below the poverty line. These issues were not raised during the election debates between the party leaders, and were rarely discussed even on the many television and radio panels during the election, and only then at the instigation of representatives of womens’ organisations or politicians of the left. It was particularly frustrating when senior Labour Party representatives, particularly party leader Eamon Gilmore, defended their proposed 50:50 split between increased taxation and reduced spending, but failed to provide a compelling social or economic reason as to why spending should be protected beyond the anaemic ‘fair and balanced’ sound bite. The deleterious impact of spending cuts on women and families, particularly those in vulnerable situations, should surely be one of the primary reasons that any Labour Party gives when defending its position. The new Programme for Government did not include an appendix detailing either the distributional or gender specific outcomes of the government’s (admittedly sketchy) fiscal policy. This should be one of the first things that Brendan Howlin orders the new Department of Public Expenditure to compile when making any budgetary changes.

However, even such a limited measure is likely to meet with overwhelming derision and even opposition from a small but economically powerful section of society. One of the difficulties confronting those who seek to achieve greater gender equality is the sometimes hysterical reaction of - it must be admitted - mainly middle-class, middle-aged men in regard to questions of gender equality and women’s rights. That this demographic dominates the media, the professions, business and the political system tends to skew public debate on gender equality towards the anecdotal and, in some cases, bizarre. There is also a remarkable coincidence between the disdain for gender equality as a valid goal and the continued belief in the ‘Irish model’ of a highly neoliberal market economy. What has emerged since the bank guarantee has been a refinement of the ‘Irish model’. Shorn of social partnership and the limited commitment to improving women’s opportunities and independence (through say, the free year of pre-school education), the ‘Irish model’ now involves actively reducing the scope of the state’s commitment in many areas and restructuring the labour market in employers’ interests while actually increasing the state’s commitment to supporting the losses of the private banking system. This new model, forged under the aegis of the IMF and EU against a cataclysmic economic landscape, does not represent the values or interests of the vast majority of Irish men and women. An economic and social crisis originating from within the private financial sector must not be allowed to turn back the clock on the advances towards gender equality achieved by the struggles of generations of women and men in Ireland.