From the ‘Soul of Haiti’ to ‘the Pluck of the Irish’: Neoliberalism and the Discourse of Resilience

The power of neoliberal discourse lies in how it contaminates and thrives on the established language we use to discuss politics and society. In particular, ideas of ‘freedom’ and the ‘individual’ now mainly operate in a shrivelled register of economic instrumentality. Audrey Bryan examines how praise of human resilience has come to mean Croppy lie down.

I recently visited the Haiti Lives photographic exhibition, which was one of a number of events to mark the one year anniversary of the January 2010 Haitian earthquake. The exhibition was coordinated by the Trinity International Development Initiative (TIDI) (TCD), in collaboration with Oxfam Ireland, with “additional images provided by the Soul of Haiti Foundation (SOH) depict[ing] life in Haiti in recent months.” The photographs supplied by Oxfam comprise a diverse set of images from those living in tented villages, to farmers tilling land, to those involved in clean-up and recovery efforts or other productive activities. Those supplied by SOH depict a far more uniform portrayal of “life in Haiti”; they exude positivity and vibrancy of the “poor-but-happy” variety, with generic, often decontextualised images of smiling faces against colourful backdrops.

The SOH newsletter, copies of which were available at the exhibition, explains that the images supplied by its foundation were intentionally chosen to represent a "positive Haiti," in stark contrast to the devastating images that became etched on people's minds in the immediate aftermath of the quake. The SOH foundation’s raison d’être is to put Haiti “on the map” as an attractive business opportunity for Irish entrepreneurs; its website lists such “incentives” as “unfilled market opportunities,” “cheap labour,” “a tariff free gateway to nearby US for certain products” and “zero corporate and income tax” as just some of the “great reasons to do business in Haiti.” The story of how modern capitalism opportunistically thrives in the context of shocks and “natural” disasters is brilliantly executed in Naomi Klein’s Shock Doctrine. Foundations like SOH, with their “just add a pinch of humanitarianism and stir,” ideology, is yet another illustration of disaster capitalism’s opportunism in action. Writing in the immediate aftermath of the 2010 Haitian earthquake, Peter Hallward wrote about the role of the kinds of “attractive” business conditions identified by the SOH foundation in exacerbating the impact of the earthquake. Among the business opportunities identified by the SOH on its website are the “export of high value fruit and veg. such as peppers (3 crops a year and very cheap labour)” and clothing sourcing and manufacturing due to “price, transport and tax/duty advantages”. The extent to which people’s lives in this part of the world are determined by international economic agendas, and the devastating impact that such “business opportunities” have on their lived realities (as opposed to the sanitised realities depicted in the SOH images in the Haiti Lives exhibition), is poignantly relayed in Stephanie Black’s documentary film Life and Debt in Jamaica.

Undeterred by, or oblivious to, such critiques, the SOH newsletter is full of references to “strong” and “vibrant,” and above all “resilient” Haitians who, following the quake "dusted themselves down and got back to work ensuring that despite it all, Haiti was back in business" (SOH Newsletter, Issue 3, January 2011). While the imagery supplied by Oxfam weaves a far more contextualised and multi-dimensional story of “Haiti Lives,” post January 2010, it too evokes a discourse of Haitian “resilience” in the wake of the earthquake. The narrative overview of the exhibition describes how the exhibition was “inspired by the strength and resilience of the Haitian people”—a discourse which is given tangible form through multiple images of Haitians who are busy “getting on with life” in the wake of the earthquake.

Jean-Bertrand Aristide recently argued that: "What we have learned in one long year of mourning after Haiti's earthquake is that an exogenous plan of reconstruction – one that is profit-driven, exclusionary, conceived of and implemented by non-Haitians – cannot reconstruct Haiti". For foundations such as the SOH, however, the project of reconstruction is primarily a battle for “business hearts and minds” more so than an infrastructural or institutional re-building programme. Through its “Brand Haiti” project, it seeks to rebuild the “spirit of the nation” and its “reputation,” as seen by its “potential trading partners, investors, tourists and even its own Diaspora”. The images it supplied to the Haiti Lives exhibition play an important role in this “nation branding programme”, seeking to promote Haiti as a destination for investment and tourism. The SOH foundation newsletter informs us that so resilient and irrepressible is the spirit of the Haitian people, and such is their “enthusiasm for success”, that “despite its pain, Haiti will continue to thrive” (SOH Newsletter, Issue 3, January 2011).

There are clear links between the SOH entrepreneurial model and the Irish “development” model. SOH’s Director, Michael Cullen, is Chief Executive and co-founder of Beacon Medical Group (BMG), the group responsible for the development of co-located private hospitals on public hospital sites in Beaumont, Cork and Limerick. But there are also similarities in terms of the ways in which the drivers of neo-liberal shaped globalisation discursively produce their casualties.

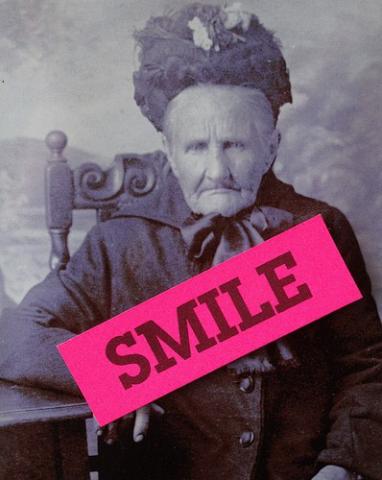

When Ireland’s EU-IMF “deal” was being “negotiated”, words like “resilience”, and “strength”, which roll off the tongue of SOH entrepreneurs, also managed to leak their way into the deliberations. EU Commissioner Olli Rehn, for example, described the Irish as a "smart, resilient and stubborn people” while Deputy Director of the IMF European Department, Ajai Chopra, appealed to our “plucky” nature. While the scale of Haiti’s long term immiseration at the hands of its colonial, neo-imperial and neo-liberal masters and Ireland’s recent financial and sovereignty crises is incommensurable, this seductive and consoling storyline of the human - and more specifically national - capacity to smile through one’s tears serves an important legitimation function for neoliberal institutions such as the IMF and the EU. As Julian Reid explains, more importantly, what is most at stake in the discourse of resilience is that it presupposes a world characterised by disaster and demands that we, as resilient subjects, bear this disaster, permanently struggling to adapt and accommodate ourselves to the world. The resilient subject, therefore, is not one which “can conceive of changing the world, its structure and conditions of possibility. But a subject which accepts the disastrousness of the world it lives in as a condition for partaking of that world and which accepts the necessity of the injunction to change itself in correspondence with the threats and dangers now presupposed as endemic.” In other words, the discourse of resilience implies that resistance is futile in the face of such inevitable disaster, and that the only recourse is to embrace neoliberalism.

The deployment of a narrative of resilience in the wake of human catastrophe and economic crisis seeks to convince us that there is little we can do to change a world characterised by disaster - a disaster which global capitalism - having orchestrated or exacerbated - in turn seeks to profit from. Those who cannot accommodate to such circumstances, of course, have only themselves to blame. And those who are plucky or resilient enough to adapt, well they can smile through their tears.

Image top via alancleaver_2000 on Flickr