Your only man

Brian O’Nuallain, better known both as the novelist Flann O’Brien and the journalist Myles na gCopaleen, was a writer capable of making jokes that everyone from academics to working men could laugh at. As we celebrate the centenary of his birth we should not forget that O’Nuallain’s works, like the man himself, contain hidden sides that reveal much about the paradoxical nature of being Irish. By Ed O’Hare.

There is an unwritten law of literary criticism which states that a great writer may be many things but they can never be funny. Perhaps it has to do with uncertainty about what defines something as humorous, or with the snobbish sentiment that to be purely amusing is to be ultimately facile, but comic writers always seem to have to wait the longest for recognition. This has certainly been the case with Brian O’Nuallain (aka Flann O’Brien aka Myles na gCopaleen). Novelist, journalist and satirist, O’Nuallain’s mastery of language is obvious to anyone who has read a page of his writings, but this wasn’t enough to stop him from becoming one of the great martyrs of modern Irish literature. Disparaged, abused and resented in his lifetime, only recently have O’Nuallain’s vast talents received a critical re-evaluation.

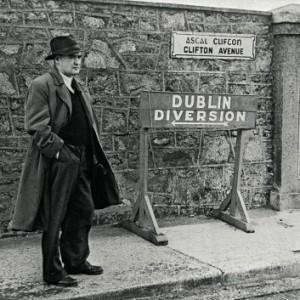

It all began so promisingly. Born in Strabane, Co. Tyrone on 5 October 1911, O’Nuallain was the eldest of twelve children in an Irish-speaking household which relocated to Dublin in 1925. Tiny in stature but outrageously intelligent, O’Nuallain flew through Synge Street CBS and Blackrock College and became a legend at UCD for his hysterically witty debating speeches. When he was 24 he sat the entry exam for the Civil Service and received the highest score that year. The death of his father when O’Nuallain was 26 was a tragedy compounded by the fact that Brian was the only breadwinner in the family and his meagre earnings had to support all of its members. The dream of a great literary career which he had nurtured, and which many had projected for him since his schooldays, had been dealt a massive blow.

Nonetheless, O’Nuallain persevered. In 1939 his radical first novel, At Swim-Two-Birds, was published and although no runaway financial success, it brought him praise from some renowned names, including Graham Greene, Dylan Thomas and, above all, James Joyce. The following year a series of sham letters to the Irish Times led to O’Nuallain being offered his own column, Cruiskeen Lawn, which first appeared in Irish and which he continued to write right up until his death. Unfortunately, it was around the same time that O’Nuallain’s literary ambitions received their biggest setback. The Third Policeman, his even more original second novel, was rejected by publishers. Deeply disappointed, he left the manuscript on a sideboard and told his friends he had misplaced it. He would never see it in print.

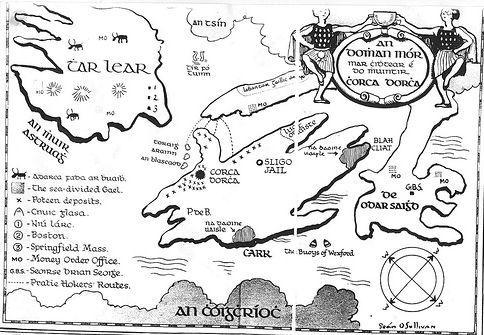

The next time O’Nuallain appeared between hard covers it was with An Beal Bocht, or The Poor Mouth, a vicious send-up of life in a Gaeltacht. While the popularity of Cruiskeen Lawn rocketed as O’Nuallain developed a regular cast of characters there would be a wait of more than twenty years before his next two novels. The Hard Life (1962) was a farce set in Dublin, while The Dalkey Archive (1964) combined comedy with science-fiction. By now O’Nuallain had been drummed out of the Civil Service due to his alcoholism and his contempt for his superiors. Indeed, he seems to have spent as much of his time as he could in the company of his drinking partners Patrick Kavanagh and Brendan Behan and away from the living death of the Customs House or the Dáil. He had married a secretary, Evelyn McDonnell, in 1948. Apart from a small pension, O’Nuallain lived off his writing from 1953 onwards, but at least his final works brought him some belated fame. Never a man of robust health, he died on April Fools’ Day 1966.

To dismiss Brian O’Nuallain’s career as a failure is to make two simple mistakes. These are to consider his oeuvre in terms of its smallness instead of its quality and to ask that most irresistible but irresponsible of questions: what if things had gone differently? On the first count, it is now acknowledged that O’Nualla

in was among the most innovative fiction writers of his generation. While most of the world was still trying to grapple with Modernism, O’Nuallain, with his bouncing, encyclopaedic combinations of mythology, literary history, science and pop culture, was pioneering Postmodernism. He was one of the earliest writers to develop a new form of subversive, intellectual humour, which has since been seen everywhere, from the novels of William Gaddis, Joseph Heller and Thomas Pynchon to television shows like Monty Python and The Simpsons. What other writer was making gags about Quantum Mechanics and the Theory of Relativity in the late 1930s? Secondly, to rate O’Nuallain’s work against the kind of books he might have produced is pointless, because it leads us to overlook his crowning achievement - the creation of an Ireland completely of his own which, despite or perhaps because of its bizarreness, reveals many truths about Irish life and the strangeness of existence.

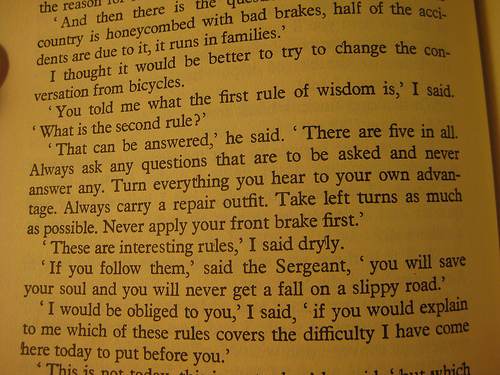

Two of his novels are masterpieces. At Swim-Two-Birds’s manic genre-hopping, mock scholarship and hilariously anarchic deflation of various forms of paddywhackery remains jaw-dropping. It is one of the few books worthy to sit on the same shelf as Gulliver’s Travels and Tristram Shandy. Even better is The Third Policeman, a novel constantly at war with its own footnotes, whose only equal in the surrealness stakes is Alice in Wonderland. Although it starts more quietly and seems to have a plot, The Third Policeman becomes a mind-bending epic of the absurd and features the now famous Atomic Theory, through the mysterious agency of which men become bicycles and bicycles adopt human personalities.

In the hands of a lesser author these books could have turned into absolute nonsense, but O’Nuallain’s fierce intelligence meant that they were always going to be far more than just comic novels. They are meditations on the nature of the creativity, and O’Nuallain gives them a Russian-doll-like structure so that we are constantly passing from one level of imagined reality to another. His worlds are governed by a pitiless anti-logic so that even the most insane acts make a distorted sense. Also, his championing of the universe of words over facts means that all time and space and all possibilities co-exist. This is why his novels can feature a house being built from the roof down, a disembodied soul called Joe, St. Augustine turning up in an underwater cave off the south coast, policemen whose duty is to steal, the mad-scientist De Selby who wants to remove all the air from the world, a police-station with only two dimensions, people who are born fully-grown adults, James Joyce working as a barman in Skerries, machines which become so small they turn invisible and an old man who has decided that all of life’s questions can be answered with the word ‘no.’

For all their jokes, what should not be forgotten about O’Nuallain’s novels is the melancholy that runs through them - a sadness which stemmed from the man himself. Part of their charm for a modern reader is their depiction of an impossibly dreary landscape in which introverted characters wander in and out of draughty houses, seedy bars, dank student digs and small, isolated farms, but this was the stagnant Ireland O’Nuallain confronted every day and it drove him to the bottle. In The Third Policeman hell is presented as a place where no real change occurs and people are doomed to perpetually re-enact the same hopeless courses of action. It doesn’t require much imagination to see where O’Nuallain, trapped in the bureaucratic heart of the intolerant Irish State, got this idea. All the same, in his novels and articles he found sources of mirth to share with others at a time when they desperately needed them. His legacy to us is the ability to laugh at ourselves.

{jathumbnailoff}

Image centre: rocket ship.