Why Marx was mostly right

Book Review: Terry Eagleton, Why Marx Was Right. (Yale, 2011). By Joseph Mahon.

Terry Eagleton is currently Distinguished Professor of English Literature at the Universities of Lancaster and Notre Dame. In his latest book, this prolific author sets out to demonstrate that it is reasonable to hold that Marx was correct - if not always, then at least mostly so. To accomplish this task, he takes ten of the most standard criticisms of Marx, in no particular order of importance, and tries to refute them one by one.

The standard criticisms of Marx (and Engels), as Eagleton perceives them, are as follows:

- Marxism is irrelevant, since "it has no bearing on the increasingly classless, socially mobile, postindustrial Western societies of the present."

- Marxism may be all very well in theory, but in practice it has led to "terror, tyranny, and mass murder on an inconceivable scale."

- Marxism is a form of determinism, since "it sees men and women simply as the tools of history, and thus strips them of their freedom and individuality."

- Marxism is a utopianism, and as such deeply delusional; "It believes in the possibility of a perfect society, without hardship, suffering, violence or conflict."

- Marxism is a form of economic determinism; it explains all human behaviour, achievement and institutions, from art and religion to politics, war, and morality, in economic terms, so that "the true complexity of human affairs is passed over for a monochrome vision of history."

- Marxism is a form of materialism, holding that all statements about all forms of consciousness may be translated, without change or loss of meaning, into statements about matter and brain activity.

- Marxism lacks a subject matter, since the working class, about which Marx and Engels wrote so much, literally no longer exists.

- Marxism is anti-democratic: it advocates violent revolution against legitimate governments, as well as rule by a self-chosen elite of professional revolutionaries.

- Marxism proclaims, and in practice quickly degenerates, into despotic rule by the State.

- Marxism is obsolete; it has been superceded as a radical politics by genuinely populist, radical movements such as feminism, gay rights, animal advocacy, and anti-globalisation.

Eagleton responds to these criticisms with characteristic brio, wit, and erudition. Capitalism has gone global, replacing a Western proletariat with a numerically much larger one in China, Brazil, India and Eastern Europe. He writes: "Tristram Hunt points out that Mike Davis's book Planet of Slums, which documents the 'stinking mountains of shit' known as slums to be found in the Lagos or Dhaka of today, can be seen as an updated version of Engels's The Condition of the Working Class. As China becomes the workshop of the world, Hunt comments, 'the special economic zones of Guangdong and Shanghai appear eerily reminiscent of 1840s Manchester and Glasgow.'"

Eagleton adopts six lines of reply to the most bellicose objection to Marxism: that in practice it has led to terror, tyranny and mass murder on an unimaginable scale. He replies as follows:

- Capitalism itself has a blood-stained history.

- Socialism was least likely to succeed in a country - Russia - "besieged by imperial Western armies, as well as threatened by counterrevolution, urban famine and a bloody civil war."

- "Marx himself was a critic of rigid dogma, military terror, political suppression and arbitrary power."

- 20th-century East European socialism offered high levels of social protection to half the citizens of Europe: "it [the USSR] managed along with its satellites to achieve cheap housing, fuel, transport and culture, full employment and impressive social services, as well as an incomparably greater degree of equality and [in the end] material well-being than those nations had previously enjoyed. Communist East Germany could boast one of the finest childcare systems in the world. The Soviet Union played a heroic role in combating the evil of fascism, as well as in helping to topple colonialist powers... All this, to be sure, is no substitute for freedom, democracy and vegetables in the shop, but neither is it to be ignored."

- So-called market socialism offers a viable alternative to the miseries of capitalism and bolshevism: in a market socialist economy "the means of production would be socially owned, while self-governing cooperatives would compete with each other in the marketplace."

- Soviet-style socialism has been replaced by a Wild West type of capitalism, "a form of daylight robbery, politely known as privatisation, joblessness for tens of millions, the loss of women's rights and the near ruin of the social welfare networks that had served these countries so well."

This defence, accomplished as it is, needs further work. Distinctions need to be drawn between Marxism, Marxism-Leninism, Stalinism, and the post-Stalinist state; between a 19th-century philosophy and 20th-century societies claiming allegiance to that philosophy.

Second, there is a nagging fear that the Left attracts control freaks who, once they get their hands on power, quickly turn into psychopaths; is there something in the very doctrinal complexity of Marxism and its variants that generates an aching for doctrinal purity and a visceral intolerance of doctrinal deviation?

Third, there is the at once pleasing and depressing fact that the historical durability of capitalism in the West is due in no small measure to the fact that it has burgled chunks of the socialist agenda for its own purposes. What is diplomatically called 'the mixed economy' is, in fact, a type of society which sees the State systematically involved in all facets of social existence, especially health, education, childcare, care of the elderly, transport and (reluctantly) banking.

The State is by far the single largest, and most protective, employer in Western economies. Unfortunately, this does not innoculate it against the misbehaviour of reckless speculators, incompetent regulators and narcissistic, deluded politicians.

Finally, the successes of the Scandinavian model of social democracy suggest that we should not be neurotically concerned about the gap between social and socialist democracy. Social democracy is the current hate-object of the far Left.

Why is this so?

It is a dogma among Marxists that socialism is synonymous with public ownership. Market socialists are then faced with the problem of squaring public ownership with market competition and practices.

But Marx distinguished between private and personal ownership. Post-capitalist society would deprive no one of his or her personal possessions; it would simply make it impossible for anyone to exploit the labour power of others.

The central idea here is that no one should be allowed to control the labour, and by extension, the life of another. The high tax, high public service type of society goes some way towards meeting this ideal by offering extensive social protection, and opportunities in life, to all citizens.

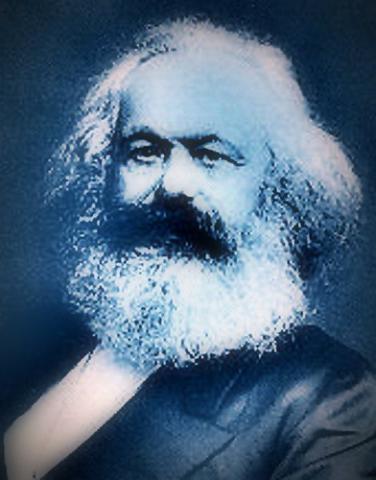

Image top: Sophoco