The vulcan of Sandycove

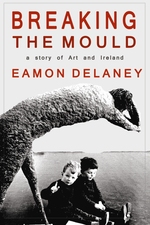

The lives of Irish artists tend to remain untold stories. Despite the incredible resurgence of interest in the work of our native painters and sculptors, the number of Irish artists who have been the subject of biographies has remained very small. All this makes Breaking The Mould, Eamon Delaney's vibrant memoir of his father, the late, great Edward Delaney, the more welcome.

From the early 1960's through to the late 1970's Edward Delaney was Irish sculpture. His strange and beautiful works in bronze were a universe away from the staid creations of previous generations. When the State sought to celebrate Ireland's national heroes, it was Delaney who rose to the challenge of fashioning these monuments. It is for these works, including the elaborate memorial to Thomas Davis on Dame Street, the haunting Famine Group and awesome statue of Wolfe Tone on the northeast corner of St. Stephen's Green, that Delaney remains best known.

Born in 1930 in Claremorris, Co. Mayo, it was Delaney's childhood experience of making posters for a visiting circus which convinced him to develop his artistic abilities. His rural background would echo in the many bronze horses, shepherds and musicians he would later make. Arriving in Dublin, he seems, with trademark bravado, to have simply strolled into the National College of Art and Design without submitting a portfolio and begun attending classes. Delaney's artistic ambitions were put firmly on track when a chance meeting with German officials overseeing the unveiling of a statue led to him being offered a scholarship to study sculpture in Munich.

Born in 1930 in Claremorris, Co. Mayo, it was Delaney's childhood experience of making posters for a visiting circus which convinced him to develop his artistic abilities. His rural background would echo in the many bronze horses, shepherds and musicians he would later make. Arriving in Dublin, he seems, with trademark bravado, to have simply strolled into the National College of Art and Design without submitting a portfolio and begun attending classes. Delaney's artistic ambitions were put firmly on track when a chance meeting with German officials overseeing the unveiling of a statue led to him being offered a scholarship to study sculpture in Munich.

The devastated Germany Delaney discovered played a profound role in shaping his Brutalist aesthetic. In Milan and Rome he perfected his craft, learning the ancient lost-wax process before heading back to Ireland. In a pair of converted cottages in Dun Laoghaire, Delaney built his own foundry and, in a period of remarkable industry, modelled, moulded and cast hundreds of magnificent bronzes, (and Eamon's recollection of the 'Dance of the Pour' in which these pieces were made is the memoir's magical highpoint) ranging in scale from a few inches to ten feet tall. All of these were characterized by Delaney's unique style, a wondrous hybridization of the abstract and figurative, and imbued great feeling and emotion. These organic forms look as though they were grown rather than sculpted. They possess a timeless quality, and could be among the first things made by mankind, or the last.

Delaney did not have to wait long for recognition. One of the most refreshing things about Breaking The Mould is that instead of the usual torpid landscape of deprivation and ignorance, the Ireland of this memoir is a place of prosperity and progress. The economic reforms of Sean Lemass and Jack Lynch engendered a cultural climate in which the new and unusual were something to be embraced. As early as 1957 Delaney was having successful one man shows and the mid-60's saw him receive a string of major commissions from institutions eager to add his unmistakable creations to their environs.

All the same, as an artist with a young family, things were very tight. Eamon amusingly recalls his father's considerable thrift, and even remembers him settling bills with a drawing or sculpture. It was only when Charles J. Haughey, a good friend and admirer of Delaney's work, introduced the artist's exemption scheme that Delaney's future in Ireland was made secure and the threat of the Tax-man finally faded away.

By the 1970's Edward Delaney was a major force in Irish art, representing the country in overseas exhibitions, designing album covers for the Chieftains, stage sets for Abbey and the Lyric Theatre in Belfast, and stunning illustrations for The Samson Riddle, a book by Delaney's friend and collaborator, the screenwriter Wolf Mankowitz. And of course, there were more sculptures: The Peace People and Marching Women series, a leviathan Sea Creature, a lonely woman called Anna, a trio of life-size figures King, Queen and Daughter, and innumerable smaller but no less elegant pieces. He even proposed a gigantic metal and glass tower for the site of Nelson's Column. Then in 1980 it was all change. Delaney departed Dublin for Carraroe and, in a brave move, gave up bronze casting for stainless steel. It was in Carraroe that Delaney conceived his greatest project, a sculpture park complete with a forest of steel trees.

By mixing together a diverse range of materials in the melting pot of memory to forge this magnificent memoir, Eamon Delaney has, in a sense, become a sculptor himself. He writes about one of the most notoriously tricky subjects, modern art, with a knowledgeable, unpretentious eye and easygoing humour. By describing the intelligence and hard work that went into the creation of his father's greatest achievements, such as that testament to humanity's indomitable spirit in the face of unthinkable suffering, the Famine Memorial, he rightly establishes Edward Delaney as one of the most important creative imaginations to emerge in this country in the last century. A stroll around St. Stephen's Green will never seem the same again.

Gallery below (left to right): Adam and Eve in Fitzgerald's Park, Cork; The Famine, in St. Stephen's Green; Thomas Davis Monument on Dame Street; Wolfe Tone in St. Stephen's Green

{yoogallery src=[/images/gallery/edward_delaney] width=[100]}

Breaking the Mould: A Story of Art and Ireland, by Eamon Delaney is published by New Island and can be purchased on their website for €16.99.

Breaking the Mould: A Story of Art and Ireland, by Eamon Delaney is published by New Island and can be purchased on their website for €16.99.