Time to get new negotiators

Irish corporation tax policy is not about attracting companies that create growth within the country in terms of jobs or through helping to develop indigious Irish enterprises through skills transfer or use of services - it's about attracting companies whose only reason for establishing a base here is tax avoidance. By Donagh Brennan.

The final draft of the Fiscal compact is now available, meaning Irish pundits can no longer say "listen, we haven't seen the final draft yet" when declaring that the requirements involved are really no different to what is in place in international agreements already. While the final treaty is regularly described as a list of German demands, there are two, broadly, that are considered to meet Germany's needs explicitly: a debt brake and a writing of the treaty into the constitution of the countries that have signed up. Given the pressure that we are told Germany is able to exert within these negotiations it is interesting which demands the Irish Government has been able to resist and which they are happy to comply with. The Government has used its negotiating skills to successfully avoid the constitutional requirement.

The final text of the treaty now says:

"NOTING that compliance with the obligation to transpose the "Balanced Budget Rule" into national legal systems through binding and permanent provisions, preferably constitutional, should be subject to the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the European Union, in accordance with Article 273 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union."

The implications of the word "preferably" shall be explored in tedious detail in the coming weeks, no doubt. One quote that will be at the fulcrum of that debate, however, was provided today by an unnamed EU offical involved in the negotiations:

"We drafted the text for the treaty so that [Enda Kenny] has a chance to avoid a referendum.

It's not in terms of likely or not likely, it is hopefully or not hopefully, so we'd hope they don't need to go to a referendum."

The argument has been that the main fiscal controlling elements of the treaty are no different to what exists already under EU law. That the treaty itself is part of EU law, given its construction, is contested, as is the remit outlined for the European Court of Justice. However, the argument that this does not move the competence over national fiscal policy to the EU more than has already been agreed to through referenda (the criteria of the Crotty judgement) is disputed by Angela Merkel.

"The debt brakes will be binding and valid forever...Never will you be able to change them through a parliamentary majority."

As Michael Taft has already pointed out, agreeing to the treaty means taking on up to €6bn more in austerity measures, which are the level of cuts required to, in theory, reach the structural deficit criteria of 0.5 % of GDP enshrined in the Austerity Treaty.

But while Old Thady might agree that the measures included in the treaty are "necessary" (because sure "when we got the few shillings, we went to the divil altogether") the treaty itself will remove any means we might have to help the economy to recover. When I say economy here, I mean, the domestic economy - that upon which the vast majority of people in Ireland depend for work, incomes, creating businesses and ultilising services and which the government mainly relies upon for tax revenue to support the things that the majority of citizens rely upon.

These regularly scheduled EU summits are supposed to initiate a number of strategies to resolve the euro debt crisis and the impending recession in the Eurozone. On Monday, the increasing unemployment in the ‘zone was also discussed, although the obvious call for investment was muted by the contradictory boilerplate demand for debt reduction through fiscal contraction. The next summit however, will raise the taxation issue once again. And here we will see how our government’s skills as negotiators are once again very selective in their deployment.

Recently it was reported that Ireland is under a “new threat” from Germany and France who see the creation of a "pan-European business tax system" as one means of stimulating economic growth.

"In a paper seen by The Irish Times, they highlight 'tax co-ordination' as being among the policies required to bring [economic growth] about. These include a quickening of moves to create a common consolidated corporate tax base (CCCTB), an initiative once dismissed by Taoiseach Enda Kenny as tax harmonisation by the ‘back door’.

The CCCTB would not harmonise tax rates but it would create a pan-European tax system for firms operating in more than one country."

From this report it appears that the measure would try to limit the ability of foreign firms using subsidiaries which are taxed individually to reduce their tax liability in the country where the parent is based. For example a German company may have a subsidiary in Ireland, which is taxed in Ireland. They also have subsidiaries in other countries, each one of which is taxed in that country, or, in the case of tax havens, not taxed. However, because the German company is able to use inter-group loans, and get tax relief here on dividends that have already been ‘taxed' in a low-tax country, its effective tax rate is considerably lower than the much vaunted 12.5%. The subsidiary is usually structured as a ‘private holding company'.

Here's how Arthur Cox describes the system:

"Tax Efficient Holding Company structures: Private holding companies incorporated and tax resident in Ireland provide tax efficient mechanisms for holding shares in subsidiary companies, and EU subsidiaries in particular. Not only do such companies benefit from certain tax exemptions but the governing company law regime offers great flexibility. Many private companies and family holding vehicles have chosen Ireland as the base of their European or intermediate holding companies. Advantages for holding companies in Ireland include dividends being payable without withholding tax to countries with which Ireland has a double taxat"ion agreement [Note: this also works with countries where no taxation agreement exists], certain capital gains tax exemptions on share disposals, a lack of CFC legislation, no thin capitalisation rules and relief from stamp duty on share transfers within 90% groups.

Recently, a Middle Eastern investor used an Irish holding company to acquire and hold their stake in a large listed German manufacturer."

In Ireland, of course, a lack of CFC legislation is seen as a good thing. Odd though that in 26 OECD countries it’s not. Although the Tories are currently trying to get rid of it in the UK, it was actually introduced while the Tories were in Office (1984) to try and cut back on the sort of practices that were undermining the British economy.

Here's Richard Murphy explaining the issues:

"In many cases, the intellectual property of companies (e.g. the patents of pharmaceutical companies and the registered trademarks of major brands) are registered in tax havens with royalty income then being paid to those subsidiary companies. This then gives rise to dispute in countries such as the UK as to where the income of the tax haven subsidiary really arose - with the UK tax authorities frequently trying to argue that at least part of that income should be taxed in the UK even though it is recorded in a tax haven. To allow the tax authorities to charge such tax, the UK and many other countries have what is called ‘controlled foreign company' (CFC) legislation that lets them deem a tax haven subsidiary of a parent company to be resident for tax purposes in the UK. [...] The decision by Ireland not to have CFC legislation cannot be chance: it must be deliberately designed to attract FDI. And it does. There can be no doubt that this form of tax relief adds immensely to the attraction of Ireland to tax minimising IT and pharmaceutical companies in particular."

Again, the advertising from Arthur Cox is exactly the same as the arguments made by the Irish Government. It is not about attracting companies that create growth within the country in terms of jobs or helping to develop indigious Irish enterprises through the tranfer of skills or use of services. The policy is about attracting companies whose only reason for establishing a base here is to avoid tax.

Given that a significant proportion of profits earned by corporations operating within Europe are filtered through the Irish system, the estimated €3 billion in tax revenue that Ireland is supposed to get from this arrangement is pitifully small.

Indeed, it appears that the real beneficiaries of this policy are companies like Arthur Cox who have managed to become not only Ireland's largest legal firm (bolstered no doubt by its ability to be awarded €60 m HSE contracts), but the 14th largest in Europe.

When Enda sits down at the next summit to discuss the CCCTB with Merkel and Sarkozy he will no doubt argue that their plans would (in the words of the Irish Times report) "diminish the attraction of the Irish regime by making it more difficult for multinationals to take advantage of the low 12.5 per cent tax rate".

Merkel for one would be right to wonder why. This is because Germany receives much more Foreign Direct Investment than Ireland, as do many counries with far higher tax rates.

Contrary to the claims of the Irish Government/Arthur Cox and a legion of Irish tax advisors, capital is attracted by prospective returns, not the ratio of profits to after-tax profits.

Increasing the tax rate would make it more attractive to companies investing here, (they usually don't like having to plough money into large capital investments like education and infrastructure, decent broadband etc) unless of course these MNCs are only coming to Ireland to avoid tax (so that capital investment by Government doesn't apply to them). If this is the sole criteria around Ireland's attractiveness the Government should acknowledge it in its statements, while also admitting that sticking to this policy is having a negative and continually depreciating impact on the broader economy.

It is not only astonishing that the government is prepared to sacrifice the development of a functioning economy by foregoing a considerable intake of tax for very little benefit, it is also mind boggling the sacrifices that they are prepared to make to defend the rate.

Again, from the 19 January Irish Times report:

"French president Nicolas Sarkozy has major reservations about the Irish policy. With the support of German chancellor Angela Merkel, he repeatedly pressed Mr Kenny last year to dilute the regime in return for an interest rate cut on Ireland's bailout."

If this in fact the case we can argue that, even though an interest rate cut is not the be all and end all in resolving our problems - far from it - the Irish Government decided that it was better to save the bacon of a thin layer of people who directly benefit from the corporation tax rate by maintaining a cost to the Irish people even though it was possible to reduce it! So now - as a result of maintaining a policy which itself is destroying our future livelihoods - we also have to pay unnecessarily high interest rates on borrowings which are being used to pay in full for a banking disaster that Irish people did nothing to create and from which they gained nothing.

So, according to our Government negotiators, we are forced to cede power to the EU to dictate how much should be cut from the spending budget, but we can refuse the demand to increase the level of taxation.

Similarly, it’s impossible to avoid paying out on unguaranteed bonds to Anglo Irish Bank, but possible to get a concession on a core German demand to avoid the stricture that would require the Irish people to decide whether we accept or not the very far-reaching measure which would deny us the ability to change the debt brakes rule through a parliamentary majority.

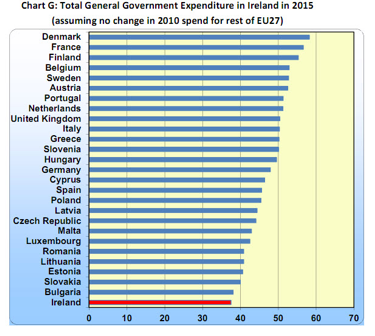

The argument as to why this is necessary is that “we went mad” with the spending. But not only does Ireland have, by far, one of the lowest corporation tax rates in the Eurozone, and far lower FDI inflows than countries with higher tax rates, it also has the one of the lowest general government expenditure levels in the EU27. As ICTU's economic advisor Tom Healy explains:

"If it is assumed that all other EU Member States were to hold their current 2010 level of spending as a % of GDP to 2015, then Ireland would reach the bottom of the list in 2015 as the lowest spending State in the EU27. Put another way, the Republic of Ireland would move from being a low-revenue and low spend State to being the lowest spend State in the EU27 and still one of the lowest-revenue collecting States."

Time to get new negotiators. {jathumbnailoff}

Image top: eiresarah.