Social democracy 'a long way from Marx'

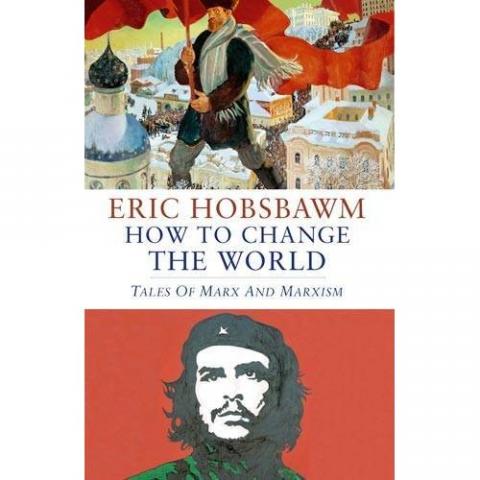

Eric Hobsbawm is summarily dismissive of social democracy in How to Change the World, writes Joseph Mahon

The claim that the Marxist classics offer no clear picture of communist society, or set of policies for that society, is a seductive one if you wish to distance Marx and Engels from Lenin, and from what Kolakowski and Judt call “the totalitarian outcome”. The founding fathers neither envisaged, nor advocated, such an outcome since they specified no outcome whatever, so they cannot be held responsible for the totalitarian one.

The totalitarian state was exclusively the work of Lenin, Stalin and their executioners. On the downside, this wasn’t the way that Lenin read the Marxist classics, especially not in his masterwork The State and Revolution. Be that as it may, if it is the case that Marx and Engels did not formulate a political project, then classical Marxism has nothing to say, and nothing to contribute to contemporary political debate. This is a depressing and scarcely believable inference; but in any event, it is not true.

Marx and Engels had relatively little (but far from nothing) to say about full-blown communism; but Engels in particular had a lot to say about the post-capitalist, transitional phase of communism. He does so in two documents which Hobsbawm cites in a different context, the two preliminary drafts of the Communist Manifesto: namely, Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith (June 1847) and Principles of Communism (October 1847).

As Engels sees it, transitional communism (which he also calls “democratic socialism”) will be post-capitalist and partly communist. It will have remnants of private property, it will leave personal property untouched, it will have organs or institutions of coercive power such as a police force and courts, and it will have armies of people engaged in occupational work or labour.

He further envisages a withering away of the coercive or authoritarian state during this phase, to be replaced by a kind of protective public administration; productive resources will progressively pass into public ownership (will be nationalised); slums will be torn down and elegant dwellings erected for colonies of working people on landed estates.

Finally, the state or public administration will assume responsibility for all the fundamental areas of social existence, such as education, childcare, banking, transport, and housing. In relation to banking, he declares that transitional communism will see “Centralisation of the credit and banking systems in the hands of the State by means of a national bank with state capital, and the suppression of all private banks and bankers.” It need hardly be added that much of this 'socialist' agenda has been adopted by the post-war European democracies.

The main question raised by Hobsbawm’s How To Change the World is this: Why does he have such a negative, dismissive attitude towards social democracy, particularly when he lavishes such a torrent of praise on Gramsci for having “pioneered a Marxist theory of politics”? In the aftermath of 1968, Daniel Cohen-Bendit asserted that the Left had two options available to it: revolution or the long march through the institutions. There have been ‘velvet’ and ‘jasmine’ revolutions, against totalitarian and autocratic regimes, but none against the Western democracies.

At the same time, the reformist alternative has yielded two kinds of society in practice: liberal and social democracy. There is a considerable ideological distance between the neo-conservative state, characterised by low taxation, low public expenditure and high income inequality (the US and the UK), and the social democratic alternative, characterised by high taxation, high public expenditure and low income inequality (Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Finland).

Scandinavian social democracy provides, not merely “some form of welfare from the cradle to the grave” (Hobsbawm), but a measurablly high form of welfare throughout a lifetime. The Nordic countries, including Finland, and to a lesser extent France and Germany, feature consistently among those countries with the highest life expectancy, highest levels of educational achievement, highest levels of gender equality, lowest levels of child and adult obesity, lowest levels of mental illness, and lowest levels of imprisonment. By any standard, these are substantial achievements, yet they do not even rate a mention from Hobsbawm. It is tempting to conclude that it is not Marx, but Hobsbawm, who lacks a vision of the good society.

For Hobsbawm, social democracy is either synonymous with, or has as it consequence, “the welfare state,” “the mixed economy,” “capitalism with a human face,” “a society of popular affluence,” and “a share of the national wealth for labour”. On the other hand, it leaves the capitalist economy intact; it supposes that the state “is capable of standing above classes,” and, as such, “is a long way from Marx.”

Above all, it is neither the theory nor the practice of “a mass party with a proletarian base”; rather, it is merely the work of European coalition politics “mobilising a socially heterogenous electorate united mainly by discontent with existing conservative regimes and a desire for a variety of reforms in state, economy and society.”

It is hard not to conclude that this is the stance of a doctrinaire Marxist historian. This is unfortunate. Marxism does not need more dogma, but less. As Sartre argued against Lukacs, Marxism should be heuristic: driven by research, attentive to what is politically feasible, anxious to abolish deep-seated inequalities (Engels on the rights of children born out of wedlock) and guided by the broad philosophical principles bequeathed by the Marxist canon.